Prostate Biopsies AHS – G2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paper Sessions

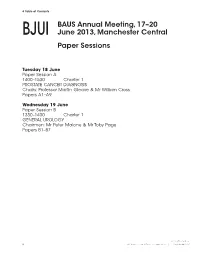

8 Table of Contents BAUS Annual Meeting, 17–20 BJUI June 2013, Manchester Central Paper Sessions Tuesday 18 June Paper Session A 1400–1530 Charter 1 PROSTATE CANCER DIAGNOSIS Chairs: Professor Martin Gleave & Mr William Cross Papers A1–A9 Wednesday 19 June Paper Session B 1330–1430 Charter 1 GENERAL UROLOGY Chairmen: Mr Peter Malone & Mr Toby Page Papers B1–B7 © 2013 The Authors 8 BJU International © 2013 BJU International | 111, Supplement 3, 8 Papers Abstracts 9 Tuesday 18 June BJUI Paper Session A 1400–1530 Charter 1 PROSTATE CANCER DIAGNOSIS Chairs: Professor Martin Gleave & Mr William Cross Papers A1–A9 A1 We then compared cancer yield in 50 Conclusion : Visualisation of each biopsy 3 D Visualisation of biopsy consecutive cases of positive prostate trajectory signifi cantly increases cancer trajectory and its clinical impact biopsies in the 2D vs. the 3D group (Part 2 detection rates and allows for a more in routine diagnostic TRUS guided of the study) through sampling of the prostate. Not only prostate biopsy Results : Th e results are tabulated as does this have a role in targeted biopsies K Narahari, A Peltier, R Van Velthoven follows but also in routine diagnostic biopsies. University Hospital of Wales, United Kingdom Introduction and Aims : Transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) guided biopsy remains Part 1 the gold standard in prostate cancer Parameter 2D USS * 3D USS *** P value diagnosis however prostate remains n = 110 n = 110 Student ’s t test perhaps the only solid organ where biopsy Age in years 64 (46–90) 65 (46–84) NS is “blind”. Traditionally the surgeon would Mean (Range) prepare a “mental image” of the prostate PSA ng/ml 9 (0.5–70) 10 (0.5–59) NS and target his biopsy cores evenly to map Mean (Range) out the prostate as best as possible. -

Prostate Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging Finding Prostate Cancer Early

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Prostate Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging Finding Prostate Cancer Early Catching cancer early often allows for more treatment options. Some early cancers may have signs and symptoms that can be noticed, but that is not always the case. ● Can Prostate Cancer Be Found Early? ● Screening Tests for Prostate Cancer ● American Cancer Society Recommendations for Prostate Cancer Early Detection ● Insurance Coverage for Prostate Cancer Screening Diagnosis and Planning Treatment After a cancer diagnosis, staging provides important information about the extent of cancer in the body and anticipated response to treatment. ● Signs and Symptoms of Prostate Cancer ● Tests to Diagnose and Stage Prostate Cancer ● Prostate Pathology ● Prostate Cancer Stages and Other Ways to Assess Risk ● Survival Rates for Prostate Cancer ● Questions To Ask About Prostate Cancer 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Can Prostate Cancer Be Found Early? Screening is testing to find cancer in people before they have symptoms. For some types of cancer, screening can help find cancers at an early stage, when they are likely to be easier to treat. Prostate cancer can often be found early by testing for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels in a man’s blood. Another way to find prostate cancer is the digital rectal exam (DRE). For a DRE, the doctor puts a gloved, lubricated finger into the rectum to feel the prostate gland. These tests and the actual process of screening are described in more detail in Screening Tests for Prostate Cancer. If the results of either of these tests is abnormal, further testing (such as a prostate biopsy) is often done to see if a man has cancer. -

Frontiers in Oncologic Prostate Care and Ablative Local Therapy

Frontiers in Oncologic Prostate Care and Ablative Local Therapy FOR MORE INFORMATION& TO REGISTER www.focalcme.com FACULTY PROGRAM DIRECTORS Arvin K. George, MD Abhinav Sidana, MD FACULTY Andre Abreu, MD Hashim U. Ahmed, MD Casey Dauw, MD Mihir Desai, MD Christopher Dixon, MD Mark Emberton, MD, FRCS Inderbir S. Gill, MD Amin Herati, MD Amar Kishan, MD Amir Lebastchi, MD Leonard S. Marks, MD Peter A. Pinto, MD Thomas J. Polascik, MD Art R. Rastinehad, DO Stephen Scionti, MD M. Minhaj Siddiqui, MD Samir S. Taneja, MD Sadhna Verma, MD Srinivas Vourganti, MD Jonathan Warner, MD James Wysock, MD FOCAL2020 AGENDA OCTOBER 3-4, 2020 Frontiers in Oncologic Prostate Care and Ablative Local Therapy WWW.FOCALCME.COM SATURDAY, OCTOBER 3, 2020 (9:25 AM - 7:00 PM EDT) SESSION 1: PROSTATE MRI/FUSION BIOPSY 9:25 am Welcome Remarks Arvin K. George, MD 9:30 am – 9:45 am The Evidence for Prostate MRI and Fusion Biopsy Peter A. Pinto, MD 9:45 am – 10:10 am Prostate MRI for the Urologist Sadhna Verma, MD 10:10 am – 10:30 am LIVE Interactive Session: Prostate MRI Case Review Art R. Rastinehad, DO SESSION 2: INTRODUCTION TO FOCAL THERAPY 10:30 am – 10:45 am Rationale for Focal Therapy Mark Emberton, MD, FRCS 10:45 am – 11:00 am Patient Selection for Focal Therapy James Wysock, MD 11:00 am – 11:10 am Role of Biomarkers in Patient Selection in Focal Therapy M. Minhaj Siddiqui, MD 11:10 am – 11:25 am Live Discussion 11:25 am – 11:40 am COFFEE TALK: Considerations of Brachytherapy for Focal Treatment Ronald M. -

Poster Sessions

TABLE OF CONTENTS BAUS Annual Meeting, 25–28 June 2012, BJUI Glasgow, SECC SUPPLEMENTS Poster Sessions Tuesday 26 June 2012 Poster Session 1 11:00–12:30 Alsh PROSTATE CANCER DIAGNOSIS Chairmen: Mr Rick Popert & Mr Garrett Durkan Posters P1–P10 Poster Session 2 11:00–12:30 Carron UPPER TRACT DISORDERS AND IMAGING Chairmen: Mr Toby Page & Mr Chandra Shekhar Biyani Posters P11–P20 Poster Session 3 14:00–16:00 Alsh SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERY Chairpersons: Mr Rakesh Heer & Mrs Caroline Moore Posters P21–P34 Poster Session 4 14:00–16:00 Carron STONES Chairpersons: Mr Daron Smith & Miss Kay Thomas Posters P35–P45 Wednesday 27 June 2012 Poster Session 5 11:00–12:30 Alsh BLADDER CANCER Chairpersons: Ms Jo Cresswell & Mr Rik Bryan Posters P46–P57 © 2012 THE AUTHORS 14 BJU INTERNATIONAL © 2012 BJU INTERNATIONAL | 109, SUPPLEMENT 7, 14–15 TABLE OF CONTENTS Poster Session 6 11:00–12:30 Carron TECHNIQUES AND INNOVATION Chairmen: Mr Ghulam Nabi & Mr John McGrath Posters P58–P67 Poster Session 7 14:00–16:00 Alsh FEMALE UROLOGY AND LUTS Chairpersons: Mr Chris Harding & Miss Mary Garthwaite Posters P68–P82 Thursday 28 June 2012 Poster Session 8 11:00–12:30 Alsh ANDROLOGY Chairmen: Mr Richard Pearcy & Mr Mike Foster Posters P83–P92 Poster Session 9 11:00–12:30 Carron RENAL CANCER Chairmen: Mr Simon Williams & Mr Neil Barber Posters P93–P102 © 2012 THE AUTHORS BJU INTERNATIONAL © 2012 BJU INTERNATIONAL | 109, SUPPLEMENT 7, 14–15 15 POSTER ABSTRACTS Tuesday 26 June 2012 BJUI Poster Session 1 SUPPLEMENTS 11:00–12:30 Alsh PROSTATE CANCER DIAGNOSIS Chairmen: Mr Rick Popert & Mr Garrett Durkan Posters P1–P10 P1 compared with the most affl uent. -

The Precision Prostatectomy: an IDEAL Stage 0, 1 and 2A Study

Open access Original article BMJ Surg Interv Health Technologies: first published as 10.1136/bmjsit-2019-000002 on 19 August 2019. Downloaded from The Precision Prostatectomy: an IDEAL Stage 0, 1 and 2a Study Akshay Sood, 1 Wooju Jeong,1 Kanika Taneja,2 Firas Abdollah,1 Isaac Palma-Zamora,1 Sohrab Arora,1 Nilesh Gupta,2 Mani Menon1 To cite: Sood A, Jeong W, ABSTRACT Key messages Taneja K, et al. The Precision Objective This study aimed to develop a preclinical model Prostatectomy: an IDEAL Stage of prostate cancer (CaP) for studying focal/hemiablation What is already known about this subject? 0, 1 and 2a Study. BMJ Surg of the prostate (IDEAL stage 0), and to use the information Interv Health Technologies Whole-gland treatment of prostate cancer (CaP) of- from the stage 0 investigation to design a novel focal ► 2019;1:e000002. doi:10.1136/ ten leads to unintended adverse functional effects, surgical treatment approach—the precision prostatectomy bmjsit-2019-000002 in particular, sexual impotence. (IDEAL stage 1/2a). ► Focal ablative techniques for treatment of local- Received 18 March 2019 Methods The IDEAL stage 0 study included simulation ized CaP have recently emerged to avoid such Revised 17 July 2019 of focal/hemiablation in whole-mount prostate functional decline; although these focal ablative Accepted 17 July 2019 specimens obtained from 100 men who had undergone techniques have shown promise, a few limitations radical prostatectomies, but met the criteria for focal/ have emerged: (1) an inability or reluctance to treat hemiablation. The IDEAL stage 1/2a was a prospective, a prostate gland >40 gm, (2) an inability to ablate single-arm, Institutional Review Board-approved study of >60% of the whole gland, (3) lack of pathological precision prostatectomy undertaken in eight men, who information, and (4) a high positive biopsy rate in the met the predetermined criteria. -

Technology Advances for Prostate Biopsy and Needle Therapies

Technology Advances for Prostate Biopsy and Needle Therapies IN 2012 an estimated 241,740 new prostate cancers ers and chemopreventive agents, and correlate novel (PCas) will be diagnosed in the United States alone.1 A PCa imaging modalities with gold standard pathology large number of them represent indolent tumors un- results from biopsy specimens. likely to limit the life span of the patient due to com- Several novel biopsy devices are currently being peting comorbidities. A recent study has shown that it investigated or are under development. They apply is necessary to treat 48 men to prevent 1 death from to biopsy and also to needle ablative therapies, such PCa, suggesting that significant overtreatment ex- as brachytherapy and cryoablation. The most com- ists.2 Still, many PCas are aggressive, causing an es- mon needle paths are transrectal and transperineal. timated 28,170 mortalities this year.1 Therefore, a Approaches are gland distributed sextant schemata comprehensive approach is urgently needed to in- or targeted biopsies. The most common image guid- crease the diagnostic accuracy of PCa.3 ance modality remains TRUS but registration (im- Freehand transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) guided age fusion) to pre-acquired PCa images, such as prostate biopsy is the most frequently performed bi- multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) opsy means for diagnosing PCa with more than 1.2 and even direct MRI guided systems, are emerging. million procedures performed annually in the United Biopsy guiding devices are based on 3-dimensional States. However, standard grayscale ultrasound pro- (3D) TRUS, probe position tracking and robotic tech- vides minimal PCa specific information, being unreli- nologies. -

Prostate Cancer N

EAU - EANM - ESTRO - ESUR - SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer N. Mottet (Chair), P. Cornford (Vice-chair), R.C.N. van den Bergh, E. Briers (Patient Representative), M. De Santis, S. Fanti, S. Gillessen, J. Grummet, A.M. Henry, T.B. Lam, M.D. Mason, T.H. van der Kwast, H.G. van der Poel, O. Rouvière, I.G. Schoots. D. Tilki, T. Wiegel Guidelines Associates: T. Van den Broeck, M. Cumberbatch, N. Fossati, G. Gandaglia, N. Grivas, M. Lardas, M. Liew, L. Moris, D.E. Oprea-Lager, P-P.M. Willemse © European Association of Urology 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 10 1.1 Aims and scope 10 1.2 Panel composition 10 1.2.1 Acknowledgement 10 1.3 Available publications 10 1.4 Publication history and summary of changes 10 1.4.1 Publication history 10 1.4.2 Summary of changes 10 2. METHODS 15 2.1 Data identification 15 2.2 Review 16 2.3 Future goals 16 3. EPIDEMIOLOGY AND AETIOLOGY 16 3.1 Epidemiology 16 3.2 Aetiology 16 3.2.1 Family history/genetics 16 3.2.2 Risk factors 17 3.2.2.1 Metabolic syndrome 17 3.2.2.1.1 Diabetes/metformin 17 3.2.2.1.2 Cholesterol/statins 17 3.2.2.1.3 Obesity 17 3.2.2.2 Dietary factors 17 3.2.2.3 Hormonally active medication 18 3.2.2.3.1 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors 18 3.2.2.3.2 Testosterone 18 3.2.2.4 Other potential risk factors 18 3.2.3 Summary of evidence and guidelines for epidemiology and aetiology 19 4. -

Refining the Risk-Stratification of Transrectal Biopsy-Detected Prostate Cancer by Elastic Fusion Registration Transperineal

World Journal of Urology (2019) 37:269–275 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-018-2459-4 TOPIC PAPER Refning the risk‑stratifcation of transrectal biopsy‑detected prostate cancer by elastic fusion registration transperineal biopsies Bertrand Covin1 · Mathieu Roumiguié1 · Marie‑Laure Quintyn‑Ranty2 · Pierre Graf3 · Jonathan Khalifa3 · Richard Aziza4 · Guillaume Ploussard1 · Daniel Portalez4 · Bernard Malavaud1 Received: 31 May 2018 / Accepted: 16 August 2018 / Published online: 25 August 2018 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Purpose To evaluate image-guided Transperineal Elastic-Registration biopsy (TPER-B) in the risk-stratifcation of low– intermediate risk prostate cancer detected by Transrectal-ultrasound biopsy (TRUS-B) when estimates of cancer grade and volume discorded with multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Methods All patients referred for active surveillance or organ-conservative management were collegially reviewed for con- sistency between TRUS-B results and MRI. Image-guided TPER-B of the index target (IT) defned as the largest Prostate Imaging-Reporting Data System-v2 ≥ 3 abnormality was organized for discordant cases. Pathology reported Gleason grade, maximum cancer core length (MCCL) and total CCL (TCCL). Results Of 237 prostate cancer patients (1–4/2018), 30 were required TPER-B for risk-stratifcation. Eight cores were obtained [Median and IQR: 8 (6–9)] including six (IQR: 4–6) in the IT. TPER-B of the IT yielded longer MCCL [Mean and (95%CI): 6.9 (5.0–8.8) vs. 2.6 mm (1.9–3.3), p < 0.0001] and TCCL [19.7 (11.6–27.8) vs. 3.6 mm (2.6–4.5), p = 0.0002] than TRUS-B of the gland. -

Newborn Circumcision Controversy

- o - THE WESTERN JOURNAL OF MEDICINE OCTOBER 1989 151 4 451 cancer, the chance of maintaining potency postoperatively is mation, atrophy, skeletal muscle, and prostatic intraepithelial only about 10%. neoplasia (a putative premalignant lesion). In our experience Surgical technical points include dividing the lateral pros- with more than 400 such biopsies, 35 % reveal carcinoma. tatic pedicles close to the prostate at least on the side opposite Although biopsy guidance may be the greatest use of to the known tumor, sacrificing the neurovascular bundle, if transrectal ultrasonography, other applications include the necessary, on the side of tumor to encompass the disease, staging of an established malignant tumor, monitoring of carefully dissecting the membranous urethra to prevent in- radiation or androgen ablation therapy, and the early detec- jury to the cavernous nerves, and using a vertical rather than tion of adenocarcinoma. The issue of screening has gener- a transverse division ofDenonvilliers's (ventral rectal) fascia ated considerable attention. The combination of trans- for perineal exposure. urethral ultrasonography and prostate-specific antigen may JOSEPH D. SCHMIDT, MD San Diego allow the identification of even a greater number of cases of REFERENCES prostate cancer. In this neoplasm, where the pathologic inci- Bahnson RR, Catalona WJ: Potency-sparing surgery for localized prostate dence far exceeds the clinically manifested disease, the ap- cancer, In Rous SN (Ed): Urology Annual. Norwalk, Conn, Appleton & Lange, propriateness of screening is controversial. A prospective, 1987, pp41-53 randomized clinical trial is mandatory to determine the effec- Pontes JE, Huben R, Wolf R: Sexual function after radical prostatectomy. Pros- tate 1986; 8:123-126 tiveness ofultrasonography not only for detecting carcinoma Walsh PC: Radical retropubic prostatectomy, In Walsh PC, Gittes RT, Perl- but, more important, for improving the rates of patient mor- mutter AD, et al (Eds): Campbell's Urology, Ed 5. -

Can Transrectal Needle Biopsy Be Optimised to Detect Nearly All Prostate Cancer with a Volume of ≥0.5 Ml? a Three-Dimensional Analysis Kent Kanao*†, James A

Urological Oncology Can transrectal needle biopsy be optimised to detect nearly all prostate cancer with a volume of ≥0.5 mL? A three-dimensional analysis Kent Kanao*†, James A. Eastham†, Peter T. Scardino†‡, Victor E. Reuter*§ and Samson W. Fine* Departments of *Pathology and †Surgery, Urology Service, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and Departments of ‡Urology and §Pathology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY, USA Objective • Detection rate for tumours with a TV of Ն0.5 mL plateaued • To investigate whether transrectal needle biopsy can be at 77% (69/90) using a 12-core (3 ¥ 4) scheme, standard 17-mm biopsy cutting length without ADBx cores. In all, 20 optimised to detect nearly all prostate cancer with a tumour Ն volume (TV) of Ն0.5 mL. of 21 (95%) tumours with a TV of 0.5 mL not detected by this scheme originated in the anterior peripheral zone or Materials and Methods TZ. • Retrospectively analysed 109 whole-mounted and entirely • Increasing the biopsy cutting length and depth/number of ADBx cores improved the detection rate for tumours with a submitted radical prostatectomy specimens with prostate Ն cancer. TVof 0.5 mL in the 12-core scheme. • Using a 22-mm cutting length and a 12-core scheme with • All tumours in each prostate were outlined on whole-mount Ն slides and digitally scanned to produce tumour maps. additional volume-adjusted ADBx cores, 100% of 0.5 mL tumours in prostates Յ 50 mL in volume and 94.7% of Tumour map images were exported to three-dimensional Ն > (3D) slicer software (http://www.slicer.org) to develop a 0.5 mL tumours in prostates 50 mL in volume were 3D-prostate cancer model. -

Transrectal Ultrasound Guided Biopsy of the Prostate

Evidence-based Guidelines for Best Practice in Health Care European Association of Urology Nurses Transrectal Ultrasound PO Box 30016 6803 AA Arnhem The Netherlands Guided Biopsy of the T +31 (0)26 389 0680 F +31 (0)26 389 0674 [email protected] Prostate www.eaun.uroweb.org 2011 European European Association ©2005 Terese Winslow, U.S. Govt. has certain rights Association of Urology of Urology Nurses Nurses Evidence-based Guidelines for Best Practice in Health Care Transrectal Ultrasound Guided Biopsy of the Prostate B. Turner Ph. Aslet L. Drudge-Coates H. Forristal L. Gruschy S. Hieronymi K. Mowle M. Pietrasik A. Vis Introduction The European Association of Urology Nurses The European Association of Urology Nurses (EAUN) was established in April 2000 to represent the interests of European urological nurses. The EAUN’s underlying goal is to foster the highest standards of urological nursing care throughout Europe. With administrative, financial and advisory support from the European Association of Urology (EAU), the EAUN also encourages research and aspires to develop European standards for education and accreditation of urology nurses. Improving current standards of urological nursing care has been top of the agenda, with the aim of directly helping our members develop or update their expertise. To fulfil this essential goal, we are publishing the latest addition to our Evidence-based Guidelines for Best Practice in Health Care series, a comprehensive compilation of theoretical knowledge and practical guidelines on Transrectal Ultrasound Guided Prostate Biopsy (TRUS Biopsy). Many thousands of prostate biopsies are undertaken in each country throughout Europe and the rest of the world each year. -

Efficacy of Intrarectal Lidocaine Hydrochloride Gel for Pain Control in Patients Undergoing Transrectal Prostate Biopsy

Clinical Urology LIDOCAINE GEL IN TRANSRECTAL PROSTATE BIOPSY International Braz J Urol Vol. 30 (5): 380-383, September - October, 2004 Official Journal of the Brazilian Society of Urology EFFICACY OF INTRARECTAL LIDOCAINE HYDROCHLORIDE GEL FOR PAIN CONTROL IN PATIENTS UNDERGOING TRANSRECTAL PROSTATE BIOPSY ALBERTO A. ANTUNES, ADRIANO A. CALADO, MARCELO C. LIMA, EVANDRO FALCÃO Service of Urology, Getúlio Vargas Hospital, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil ABSTRACT Objective: To determine the efficacy of intrarectal lidocaine hydrochloride gel in reducing pain in patients undergoing transrectal prostate biopsy. Materials and Methods: During the period from June to November 2002, 72 patients under- going transrectal prostate biopsy at an outpatient service were prospectively randomized. Patients were divided into 2 groups. In group 1, 20 mL of 2% lidocaine gel were administered by intrarectal route 15 minutes before biopsy. In group 2 (placebo), 20 mL of ultrasound gel were administered under the same conditions. At the end of the procedure, patients were asked to classify the discomfort degree observed during the procedure through a verbal pain scale. Statistical analysis was performed through qui-square test. Results: The majority of patients in both groups presented slight pain on the examination, and 26 patients (76.4%) from group 1, and 26 (68.3%) patients from group 2 reported slight pain or no pain at all (p > 0.05). Moderate or intense pain was felt by 23.4% of patients in group 1 and 31.5% of patients in group 2 (p > 0.05). Conclusions: We concluded that lidocaine probably exerts a minimal effect on patients’ tol- erance to pain on transrectal prostate biopsy.