Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Music Review EDITIONS of MUSIC a Study That Is Complex, Detailed and Seems to Me to Reach Pretty Plausible Insights

Early Music Review EDITIONS OF MUSIC a study that is complex, detailed and seems to me to reach pretty plausible insights. His thesis in brief is ‘that the nativity of Christ is BOOKS represented in the first sonata in G minor while the juxtaposed D minor partita and C major sonata are the Ben Shute: Sei Solo: Symbolum? locus of passion-resurrection imagery.’ He acknowledges The Theology of J. S. Bach’s solo violin works that there have been both numerological and emotion- Pickwick Publications, Eugene, Oregon based interpretations in these areas, but none relying ISBN 978-1-4982-3941-7 on firm musicological bases. These he begins to lay out, xxvii+267pp, $28.00 undergirding his research with a sketch of the shift from thinking of music as en expression of the divine wisdom, his is not the first monograph to employ a variety an essentially Aristotelian absolute, towards music as a of disciplines to delve beneath the surface of a more subjective expression of human feeling, revealing the Tgroup of surviving compositions by Bach in the drama and rhetoric of the ‘seconda prattica.’ In Germany hope of finding a hidden key to their understanding and these two traditions – ratio and sensus – remained side by interpretation: nor will it be the last. But what is unusual side until the 18th century, and the struggle to balance the about Benjamin Shute is that he does not go overboard two is evident in Bach’s work. So stand-alone instrumental for the one-and-only solution, instead adopting a multi- music has a theological proclamation in its conviction faceted approach to unearthing the composer’s intentions. -

'Dream Job: Next Exit?'

Understanding Bach, 9, 9–24 © Bach Network UK 2014 ‘Dream Job: Next Exit?’: A Comparative Examination of Selected Career Choices by J. S. Bach and J. F. Fasch BARBARA M. REUL Much has been written about J. S. Bach’s climb up the career ladder from church musician and Kapellmeister in Thuringia to securing the prestigious Thomaskantorat in Leipzig.1 Why was the latter position so attractive to Bach and ‘with him the highest-ranking German Kapellmeister of his generation (Telemann and Graupner)’? After all, had their application been successful ‘these directors of famous court orchestras [would have been required to] end their working relationships with professional musicians [take up employment] at a civic school for boys and [wear] “a dusty Cantor frock”’, as Michael Maul noted recently.2 There was another important German-born contemporary of J. S. Bach, who had made the town’s shortlist in July 1722—Johann Friedrich Fasch (1688–1758). Like Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767), civic music director of Hamburg, and Christoph Graupner (1683–1760), Kapellmeister at the court of Hessen-Darmstadt, Fasch eventually withdrew his application, in favour of continuing as the newly- appointed Kapellmeister of Anhalt-Zerbst. In contrast, Bach, who was based in nearby Anhalt-Köthen, had apparently shown no interest in this particular vacancy across the river Elbe. In this article I will assess the two composers’ positions at three points in their professional careers: in 1710, when Fasch left Leipzig and went in search of a career, while Bach settled down in Weimar; in 1722, when the position of Thomaskantor became vacant, and both Fasch and Bach were potential candidates to replace Johann Kuhnau; and in 1730, when they were forced to re-evaluate their respective long-term career choices. -

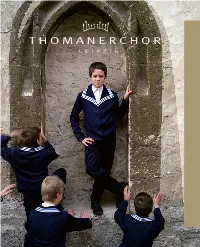

T H O M a N E R C H

Thomanerchor LeIPZIG DerThomaner chor Der Thomaner chor ts n te on C F o able T Ta b l e o f c o n T e n T s Greeting from “Thomaskantor” Biller (Cantor of the St Thomas Boys Choir) ......................... 04 The “Thomanerchor Leipzig” St Thomas Boys Choir Now Performing: The Thomanerchor Leipzig ............................................................................. 06 Musical Presence in Historical Places ........................................................................................ 07 The Thomaner: Choir and School, a Tradition of Unity for 800 Years .......................................... 08 The Alumnat – a World of Its Own .............................................................................................. 09 “Keyboard Polisher”, or Responsibility in Detail ........................................................................ 10 “Once a Thomaner, always a Thomaner” ................................................................................... 11 Soli Deo Gloria .......................................................................................................................... 12 Everyday Life in the Choir: Singing Is “Only” a Part ................................................................... 13 A Brief History of the St Thomas Boys Choir ............................................................................... 14 Leisure Time Always on the Move .................................................................................................................. 16 ... By the Way -

JS BACH (1685-1750): Violin and Oboe Concertos

BACH 703 - J. S. BACH (1685-1750) : Violin and Oboe Concertos Johann Sebastian Bach was born on March 21 st , l685, the son of Johann Ambrosius, Court Trumpeter for the Duke of Eisenach and Director of the Musicians of the town of Eisenach in Thuringia. For many years, members of the Bach family throughout Thuringia had held positions such as organists, town instrumentalists, or Cantors, and the family name enjoyed a wide reputation for musical talent. By the year 1703, 18-year-old Johann Sebastian had taken up his first professional position: that of Organist at the small town of Arnstadt. Then, in 1706 he heard that the Organist to the town of Mülhausen had died. He applied for the post and was accepted on very favorable terms. However, a religious controversy arose in Mülhausen between the Orthodox Lutherans, who were lovers of music, and the Pietists, who were strict puritans and distrusted art. So it was that Bach again looked around for more promising possibilities. The Duke of Weimar offered him a post among his Court chamber musicians, and on June 25, 1708, Bach sent in his letter of resignation to the authorities at Mülhausen. The Weimar years were a happy and creative time for Bach…. until in 1717 a feud broke out between the Duke of Weimar at the 'Wilhelmsburg' household and his nephew Ernst August at the 'Rote Schloss’. Added to this, the incumbent Capellmeister died, and Bach was passed over for the post in favor of the late Capellmeister's mediocre son. Bach was bitterly disappointed, for he had lately been doing most of the Capellmeister's work, and had confidently expected to be given the post. -

Motetten Und Orchesterwerke Der Familie Bach Die Familie Bach Von Angela Gehann-Dernbach

Einführung – Motetten und Orchesterwerke der Familie Bach Die Familie Bach von Angela Gehann-Dernbach Die Familie Bach war ein weit verzweigtes Musikergeschlecht, aus dem von der zweiten Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts bis zur Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts in Mitteldeutschland zahlreiche Stadtmusiker, Organisten und Komponisten entstammten. Man unterscheidet für diese Künstlerfamilie die beiden Hauptlinien: Erfurter Linie Arnstädter Linie Die Familie Bach beherrschte in Erfurt über ein ganzes Jahrhundert das musikalische Leben derart, dass noch 1793 alle Stadtpfeifer „Bache“ genannt wurden, obwohl längst keiner dieses Namens mehr unter ihnen lebte. Der erste Musiker dieser Familie war Hans Bach (1580-1626), der Urgroßvater von Johann Sebastian Bach, der zwar das Handwerk des Bäckers gelernt hat, jedoch als Spielmann zwischen Gotha, Eisenach und Arnstadt seinen Lebensunterhalt verdient hat und auch von weiter außerhalb geholt wurde. Johann Bach (1604-1673) ist der älteste als Komponist beglaubigte Vertreter der Musikerfamilie Bach und ältester Sohn von Hans Bach. Er gilt als der Begründer der Erfurter Linie der Familie und war ein Großonkel von Johann Sebastian Bach. Er arbeitet als Spielmann in verschiedenen thüringischen Städten, übernimmt dann die Stadtpfeiferstelle in Suhl und wird Organist in Arnstadt und ab 1628 in Schweinfurt. 1634 wird er in Wechmar Organist und 1635 Direktor der Erfurter Ratsmusik. Christoph Bach (1613-1661) war der zweite Sohn von Hans Bach sowie Großvater von Johann Sebastian Bach. Nach seinen musikalischen Ausbildungsjahren – sicher zunächst beim Vater und möglicherweise auch beim Suhler Stadtpfeifer Hoffmann – ist er um 1633 wieder in Wechmar als Stadtmusikant und „fürstlicher Bedienter“. Christoph Bach war von 1642 bis 1652 Ratsmusikant in Erfurt. 1654 ging er nach Arnstadt als „gräflicher Hof- und Stadtmusikus“. -

Benjamin Alard

THE COMPLETE WORK FOR KEYBOARD TOWARDS THE NORTH VERS LE NORD Benjamin Alard Organ & Claviorganum FRANZ LISZT JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750) The C omplete W orks for Keyboard Intégrale de l’Œuvre pour Clavier / Das Klavierwerk Towards the North Vers le Nord | Nach Norden Lübeck Hambourg DIETRICH BUXTEHUDE (1637?-1707) JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH 1 | Choralfantasie “Nun freut euch, lieben Christen g’mein” BuxWV 210 14’31 1 | Toccata BWV 912a, D major / Ré majeur / D-Dur 12’20 Weimarer Orgeltabulatur 2 | Choral “Jesu, meines Lebens Leben” BWV 1107 1’44 JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH JOHANN PACHELBEL 2 | Choral “Herr Christ, der einig Gottes Sohn” BWV Anh. 55 2’22 3 | Choral “Kyrie Gott Vater in Ewigkeit” 2’44 3 | Choral “Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern” BWV 739 4’50 Weimarer Orgeltabulatur JOHANN PACHELBEL (1653-1706) JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH 4 | Fuge, B minor / si mineur / h-Moll 2’46 4 | Choral “Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier” BWV 754 3’22 Weimarer Orgeltabulatur 5 | Fantasia super “Valet will ich dir geben” BWV 735a 3’42 6 | Fuge BWV 578, G minor / sol mineur / g-Moll 3’35 JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH 7 | Fuge “Thema Legrenzianum” BWV 574b, C minor / ut mineur / c-Moll 6’17 5 | Choral “Ach Herr, mich armen Sünder” BWV 742 2’11 8 | Fuge BWV 575, C minor / ut mineur / c-Moll 4’16 6 | Fuge über ein Thema von A. Corelli BWV 579, B minor / si mineur / h-Moll 5’24 7 | Choral “Christ lag in Todesbanden” BWV 718 4’57 JOHANN ADAM REINKEN (1643?-1722) 8 | Fuge BWV 577, G major / Sol majeur / G-Dur 3’43 9 | Choralfantasie “An Wasserflüssen Babylon” 18’42 9 | Partite -

Baroque and Classical Style in Selected Organ Works of The

BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL STYLE IN SELECTED ORGAN WORKS OF THE BACHSCHULE by DEAN B. McINTYRE, B.A., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee Accepted Dearri of the Graduate jSchool December, 1998 © Copyright 1998 Dean B. Mclntyre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for the general guidance and specific suggestions offered by members of my dissertation advisory committee: Dr. Paul Cutter and Dr. Thomas Hughes (Music), Dr. John Stinespring (Art), and Dr. Daniel Nathan (Philosophy). Each offered assistance and insight from his own specific area as well as the general field of Fine Arts. I offer special thanks and appreciation to my committee chairperson Dr. Wayne Hobbs (Music), whose oversight and direction were invaluable. I must also acknowledge those individuals and publishers who have granted permission to include copyrighted musical materials in whole or in part: Concordia Publishing House, Lorenz Corporation, C. F. Peters Corporation, Oliver Ditson/Theodore Presser Company, Oxford University Press, Breitkopf & Hartel, and Dr. David Mulbury of the University of Cincinnati. A final offering of thanks goes to my wife, Karen, and our daughter, Noelle. Their unfailing patience and understanding were equalled by their continual spirit of encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT ix LIST OF TABLES xi LIST OF FIGURES xii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES xiii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xvi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 11. BAROQUE STYLE 12 Greneral Style Characteristics of the Late Baroque 13 Melody 15 Harmony 15 Rhythm 16 Form 17 Texture 18 Dynamics 19 J. -

The End Is Nigh: Reflections of Philipp Nicolai's Eschatology in BWV 1 and BWV 140

The End is Nigh: Reflections of Philipp Nicolai's Eschatology in BWV 1 and BWV 140 Master's Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Music Dr. Eric Chafe, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts in Musicology by Hannah Spencer May 2015 ABSTRACT The End is Nigh: Reflections of Philipp Nicolai's Eschatology in BWV 1 and BWV 140 A thesis presented to Department of Music Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Hannah Spencer In his mission to create a better repertoire of "well-regulated church music to the Glory of God," J.S. Bach utilized every aspect of his craft. Aside from the rich texts penned by his anonymous librettist, Bach intentionally utilized specific musical gestures to intertwine the Gospel into each layer of his compositions. In the case of BWV 1 and BWV 140 , Bach makes compositional choices that allow him to depict the eschatological viewpoint of Phillip Nicolai, the Lutheran theologian who penned the chorales used as the basis of these chorale cantatas. By analyzing Bach's use of such devices as large-scale harmonic patterns, melodic motives, and the structural use of chiasm, the depiction of motion between the realms of Heaven and Earth becomes clear. More than simply "church music," Bach's cantatas are musical sermons of intricate detail. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract..........................................................................................................................................ii -

Yi 54 Wilhelm Rust (1822-1892) Komponist, Bachforscher Und Thomaskantor

Yi 54 Wilhelm Rust (1822-1892) Komponist, Bachforscher und Thomaskantor Wilhelm Rust, Enkel des Komponisten Friedrich Wilhelm Rust, wurde am 15. August 1822 in Dessau geboren, er starb am 2. Mai 1892 in Leipzig. Rust studierte von 1840 bis 1843 an der Dessauer Singakademie. Er war Schüler von Friedrich Schneider und von seinem Onkel Wilhelm Karl Rust. Nach seiner Tätigkeit als Privatlehrer einer adligen Familie in Ungarn. war Rust ab 1849 Klavier-, Gesangs- und Kompositionslehrer in Berlin. 1857 wurde Rust Mitglied der Sing-Akademie zu Berlin und des von Georg Vierling gegründeten Bachvereins. Verdienste erwarb er sich als Herausgeber von 26 Bänden der ersten Gesamtausgabe der Werke Johann Sebastian Bachs, für die er seit 1858 hauptverantwortlich war. 1861 übernahm er die Stelle als Organist an der Lukaskirche und war seit 1862 Leiter des Chores des Bachvereins. 1868 wurde er zum Ehrendoktor der Universität Marburg ernannt. Seit 1870 unterrichtete er zudem am Sternschen Konservatorium in Berlin. 1878 zog Rust nach Leipzig und wurde Organist der Thomaskirche in Leipzig, sowie von 1880 - 1892 Thomaskantor. Rust komponierte hauptsächlich Kirchenmusik. Die Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt in Halle (Saale) ersteigerte 2008 einen Teilnachlass Rusts. Bei dessen Durchsicht kam eine, durch Rust gefertigte, bis dahin unbekannte, Abschrift einer Choralphantasie von Johann Sebastian Bach zutage, von der bis dahin nur die ersten fünf Takte nachgewiesen waren. Umfang: 1 Kasten Zeitlicher Umfang: 1862-1925 Teilnachlass Yi 54 I Manuskripte Yi 54 I 1 3tes Capriccio ( in D-moll) für Pianoforte. Componiert von W. Rust. Deregnyö, September 1846. Notenmanuskript. 4 Blatt, geheftet, 2°. Yi 54 I 2 Impromtu hongrois à la Csárdás par W. -

Einleitung 2. Fass. Fußnoten.Qxp 11.11.2010 11:27 Seite 1

Einleitung 2. Fass. Fußnoten.qxp 11.11.2010 11:27 Seite 1 7 Einleitung Die beiden Werkgruppen des vorliegenden Bandes nehmen in Bachs Schaffen einen auch innerhalb der Orgelmusik eine gewisse Tradition aufzuweisen, an die Bach besonderen Platz ein. Sie gehören Gattungen an, die am Anfang des 18. Jahrhunderts anknüpfen konnte. Hier ist in erster Linie an die französische Orgeltradition zu den- der instrumentalen Ensemblemusik zugeordnet wurden und der Tastenmusik im ken, in der eine der wichtigsten Formen – das Trio für zwei Manuale und Pedal – auf Grunde fremd waren. Es ist deshalb nicht verwunderlich, dass es sich bei einem wich- dem kammermusikalischen Modell eines langsamen Triosatzes für zwei Violinen und tigen Teil der Stücke um Bearbeitungen handelt: So basieren die Konzerte auf Generalbass beruht. Bachs Kenntnis solcher Sätze ist für die Drucksammlungen von Streicherkonzerten anderer Komponisten, die Sonaten gehen zum Teil auf eigene Boyvin, Du Mage, Grigny und Raison belegt.2 Kammermusikwerke zurück. Weitere verbindende Elemente – natürlich vor dem Innerhalb der mittel- und norddeutschen Orgeltradition vor Bach wurde der Triosatz Hintergrund der Besonderheiten dieser Werkgattungen – sind die Anlage „à 2 Clav. mit obligatem Pedal dagegen fast ausschließlich mit dem choralgebundenen Spiel in e Ped.“ sowie die Dreisätzigkeit. Verbindung gebracht.3 Dabei herrscht jener Satztyp vor, bei dem die Choralmelodie ins Pedal verlegt und als eine Art Generalbasslinie neu interpretiert wird. Choraltrios, Die Sechs Sonaten und einzelne Sonatensätze bei denen die Choralmelodie in einer oder beiden Oberstimmen mehr oder weniger In den sechs Sonaten für Orgel BWV 525–530 verbinden sich verschiedene Merkmale koloriert auftritt und das Pedal eine reine Generalbassfunktion übernimmt, sind viel von Bachs kompositorischem Schaffen der 1720er Jahre. -

Helmuth Rilling to Conduct Bach Choral Masterworks

holiday 2006-2007 vol xv · no 4 music · worship · arts Prismyale institute of sacred music common ground for scholarship and practice Helmuth Rilling to Conduct Bach Choral Masterworks Helmuth Rilling, the world renowned conductor, teacher, and Bach scholar, will present a series of lecture/concerts, culminating in a full performance of several choral masterworks of J.S. Bach. The series, entitled Reflections on Bach: Music for Christmas Day 1723, will be presented over three days. The lecture/concerts will consist of talks with musical illustrations, followed by a performance of the work. Part I (Christen, ätzet diesen Tag) will take place on Thursday, January 18 at 8 pm at Sprague Memorial Hall, 470 College St., in New Haven, with Part II (Magnificat in Eb) the following evening (Friday, January 19) at 8pm, also at Sprague Memorial Hall. Tickets for the lecture/concerts are free, and available at 203-432-4158. On Saturday, January 20, there will be a concert performance at 8 pm at Woolsey Hall, corner College and Grove. The concert is free and open to the public; no tickets are required. Helmuth Rilling is known internationally for his lecture/ concerts, as well as for his more than 100 recordings on the Vox, Nonesuch, Columbia, Nippon, CBS, and Turnabout labels. He now records exclusively for Hänssler, for whom he has recorded the complete works of J.S. Bach on 172 CDs. Rilling is the founder of the acclaimed Gächinger Kantorei, the Oregon Bach Festival, the International Bach Academy (Stuttgart), which has been awarded the UNESCO Music Prize, and academies in Buenos Aires, Cracow, Prague, Moscow, Budapest, Santiago de Compostela, and Tokyo. -

Vocal Bach CV 40.398/30 KCMY Thevocal Sacred Vocal Music Stuttgart Bach Editions Complete Edition in 23 Volumes Urtext for Historically Informed Performance

Cantatas · Masses · Oratorios Bach Passions · Motets vocal Bach CV 40.398/30 KCMY Thevocal Sacred Vocal Music Stuttgart Bach Editions Complete Edition in 23 volumes Urtext for historically informed performance • The complete sacred vocal music by J. S. Bach • Musicologically reliable editions for the practical pursuit of music, taking into account the most current state of Bach research • Informative forewords on the work’s history, reception and performance practice • Complete performance material available: full score, vocal score, choral score, and orchestral parts • carus plus: innovative practice aids for choir singers (carus music, the choir app, Carus Choir Coach, practice CDs) and vocal scores XL in large print for the major choral works available • With English singable texts www.carus-verlag.com/en/composers/bach available from: for study & performance Johann Sebastian Bach: The Sacred Vocal Music Carus has placed great importance on scholarly new editions of the music. But the editions always have the performance in mind. Complete Edition in 23 volumes Schweizer Musikzeitung Edited by Ulrich Leisinger and Uwe Wolf in collaboration with the Bach-Archiv Leipzig With the Bach vocal project, we have published Wherever the source material allowed a reconstruc- • Reader-friendly and handy format Reconstructions Johann Sebastian Bach’s complete sacred vocal tion to be made, and the works were also relevant (like a vocal score) Pieter Dirksen: BWV 1882 music in modern Urtext editions geared towards for practical performance, Bach’s fragmentary Andreas Glöckner / Diethard Hellmann: BWV 2473 historically- informed performance practice. We are surviving vocal works have been included in the • User-friendly order following the Diethard Hellmann: BWV 186a3, 197a3 convinced that the needs of performing musicians Bach vocal publishing project, and some have been Bach Works Catalogue Klaus Hofmann: BWV 80b3, 1391, 1573 are best met by a scholarly authoritative music text, published for the first time in performable versions.