CG 978394115941.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

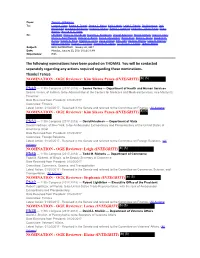

The Following Nominations Have Been Posted on THOMAS. You Will Be Contacted Separately Regarding Any Actions Required Regarding These Nominations

From: Teresa L. Williamson To: Lorna A. Syme; Rachel K. Dowell; Sandra S. Mabry; Keith Labedz; Leigh J. Francis; Jim Robertson; Jack MacDonald; Stephanie Nonluecha; Megan V. Khaner; Patrick J. Lightfoot; Kimberly L. Sikora Panza; Elaine Newton; Monica M. G. Ashar Cc: LEGTEAM; Emory A. Rounds III; Brandon L. Bunderson; Vincent Salamone; Steven Corbally; Grace A. Clark; Cheryl L. Kane-Piasecki; Deborah J. Bortot; Dale A. Christopher; Nicole Stein; Daniel L. Skalla; Elizabeth D. Horton; Wendy G. Pond; Heather A. Jones; Diana Veilleux; Seth Jaffe; David A. Meyers; Ciara M. Guzman; Patrick Shepherd; Rodrick T. Johnson; Kimberley H. Kaplan; Christopher J. Swartz; Jaideep Mathai Subject: NEW NOMINATION - January 20, 2017 Date: Monday, January 23, 2017 10:58:14 AM Importance: High The following nominations have been posted on THOMAS. You will be contacted separately regarding any actions required regarding these nominations. Thanks! Teresa NOMINATION - OGE Reviewer: Kim Sikora Panza (INTEGRITY) (b) (5) PN49 — 115th Congress (2017-2018) — Seema Verma — Department of Health and Human Services Seema Verma, of Indiana, to be Administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, vice Marilyn B. Tavenner. Date Received from President: 01/20/2017 Committee: Finance Latest Action: 01/20/2017 - Received in the Senate and referred to the Committee on Finance. (All Actions) NOMINATION - OGE Reviewer: Kim Sikora Panza (INTEGRITY) (b) (5) PN53 — 115th Congress (2017-2018) — David Friedman — Department of State David Friedman, of New York, to be Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the United States of America to Israel. Date Received from President: 01/20/2017 Committee: Foreign Relations Latest Action: 01/20/2017 - Received in the Senate and referred to the Committee on Foreign Relations. -

U.S. Trade Policy Agenda Hearing Committee on Ways

U.S. TRADE POLICY AGENDA HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MARCH 21, 2018 Serial No. 115–FC08 Printed for the use of the Committee on Ways and Means ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 33–807 WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Sep 11 2014 05:57 Mar 20, 2019 Jkt 033807 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 I:\WAYS\OUT\33807.XXX 33807 COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS KEVIN BRADY, Texas, Chairman SAM JOHNSON, Texas RICHARD E. NEAL, Massachusetts DEVIN NUNES, California SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan DAVID G. REICHERT, Washington JOHN LEWIS, Georgia PETER J. ROSKAM, Illinois LLOYD DOGGETT, Texas VERN BUCHANAN, Florida MIKE THOMPSON, California ADRIAN SMITH, Nebraska JOHN B. LARSON, Connecticut LYNN JENKINS, Kansas EARL BLUMENAUER, Oregon ERIK PAULSEN, Minnesota RON KIND, Wisconsin KENNY MARCHANT, Texas BILL PASCRELL, JR., New Jersey DIANE BLACK, Tennessee JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York TOM REED, New York DANNY DAVIS, Illinois MIKE KELLY, Pennsylvania LINDA SA´ NCHEZ, California JIM RENACCI, Ohio BRIAN HIGGINS, New York PAT MEEHAN, Pennsylvania TERRI SEWELL, Alabama KRISTI NOEM, South Dakota SUZAN DELBENE, Washington GEORGE HOLDING, North Carolina JUDY CHU, California JASON SMITH, Missouri TOM RICE, South Carolina DAVID SCHWEIKERT, Arizona JACKIE WALORSKI, Indiana CARLOS CURBELO, Florida MIKE BISHOP, Michigan DARIN LAHOOD, Illinois DAVID STEWART, Staff Director BRANDON CASEY, Minority Chief Counsel ii VerDate Sep 11 2014 05:57 Mar 20, 2019 Jkt 033807 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 I:\WAYS\OUT\33807.XXX 33807 C O N T E N T S Page Advisory of March 21, 2018, announcing the hearing ......................................... -

MAGA Hangover: Trump Administration Independent Agency Leaders Have Held Onto 24 Key Posts Under the Biden Administration and 104 Executive Agency Appointments

MAGA Hangover: Trump Administration Independent Agency Leaders Have Held Onto 24 Key Posts Under The Biden Administration And 104 Executive Agency Appointments SUMMARY: Following the outgoing administration’s “quiet push to salt federal agencies with Trump loyalists,” an Accountable.US review has found that, as of March 1, 2021, at least 24 Trump administration independent executive agency leaders who are uniquely positioned to undermine President Biden’s agenda have remained in government positions following the transition from the Trump to Biden administrations. This includes at least five figures who were involved with voting issues during the 2020 election, five figures in the labor mediation sphere, two figures in the Social Security Administration, and two questionable figures involved in setting energy market regulations. These figures include: • Louis DeJoy—The embattled Postmaster General accused of undermining mail service to help sway the 2020 election for Trump, for which he was sued by multiple advocacy groups, has remained on under the Biden Administration. • Donald Palmer—An Election Assistance Commission Commissioner who attempted to promote in- person voting during the COVID-19 pandemic, worked to undermine open and fair elections as a Virginia State election official, and was named among “voter fraud conspiracy theorists” by a civil rights group for assisting Trump’s 2016 voter fraud commission, has remained on under the Biden Administration. • James "Trey" Trainor—A Federal Election Commissioner with a rich history of pushing racial gerrymandering and noted opposition of campaign finance regulation, has remained on under the Biden Administration. • Allen Dickerson—A Federal Election Commission Commissioner who repeatedly fought against campaign finance regulations and was the top paid employee of a Koch-funded think tank, has remained on under the Biden Administration. -

US Executive Branch Update May 6, 2020

US Executive Branch Update May 6, 2020 This is a daily update (Monday through Looking Ahead: Vice President Pence is scheduled to visit Iowa on Friday, May 8, 2020. He will participate in a Saturday) on US executive branch discussion with faith leaders about responsibly (Executive Branch) schedules, notable reopening houses of worship in accordance with guidelines. The Vice President will also visit Hy-Vee developments and a synopsis of Headquarters and participate in a roundtable event with President Trump’s social media activities. agriculture and food supply leaders to discuss the US The report further provides a snapshot of food supply chain. the Executive Branch’s priorities via daily White House Briefing | May 6, 2020 press releases. 4:00 p.m. EDT – Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany We report on the daily public event schedules for the holds a briefing | James S. Brady Briefing Room President of the United States (POTUS) and Vice President of the United States (VPOTUS), as released by the White House; therefore, time for some scheduled Recap of Tuesday, May 5, 2020 items may change daily in real-time. The notable Note: All colored text denotes hyperlinks. Purple colored developments provided in this update typically include a hyperlink spotlights COVID-19 developments. listing of executive actions; a selection of departmental press releases and publications from the day prior; and The White House information on or related to coronavirus disease 2019 Remarks by President Trump at Honeywell International (COVID-19); among other information. Inc. Mask Production Facility | Phoenix, Arizona (AZ) POTUS’ Schedule | May 6, 2020 Remarks by President Trump Before Air Force One Departure (re: reopening the economy/virus 12:15 p.m. -

Trump Administration Key Policy Personnel Updated: February 5, 2017 Positions NOT Subject to Senate Confirmation in Italics ______

Trump Administration Key Policy Personnel Updated: February 5, 2017 Positions NOT subject to Senate confirmation in italics ______________________________________________________________________________________________ White House Chief of Staff: Reince Priebus Priebus is the former Chairman of the Republican National Committee (RNC). He previously worked as chairman of the Republican Party of Wisconsin. He has a long history in Republican politics as a grassroots volunteer. He worked his way up through the ranks of the Republican Party of Wisconsin as 1st Congressional District Chairman, State Party Treasurer, First Vice Chair, and eventually State Party Chairman. In 2009, he served as General Counsel to the RNC, a role in which he volunteered his time. White House Chief Strategist and Senior Counselor: Stephen Bannon Bannon worked as the campaign CEO for Trump’s presidential campaign. He is the Executive Chairman of Breitbart News Network, LLC and the Chief Executive Officer of American Vantage Media Corporation and Affinity Media. Mr. Bannon is also a Partner of Societe Gererale, a talent management company in the entertainment business. He has served as the Chief Executive Officer and President of Genius Products, Inc. since February 2005. Attorney General: Senator Jeff Sessions (R-Ala.) Sen. Sessions began his legal career as a practicing attorney in Russellville, Alabama, and then in Mobile. Following a two- year stint as Assistant United States Attorney for the Southern District of Alabama, Sessions was nominated by President Reagan in 1981 and confirmed by the Senate to serve as the United States Attorney for Alabama’s Southern District, a position he held for 12 years. Sessions was elected Alabama Attorney General in 1995, serving as the state’s chief legal officer until 1997, when he entered the United States Senate. -

Infographic: a Look at Donald Trump's Administration

Infographic: A look at Donald Trump’s administration - The Boston Globe BOS 0 2 nd Prd NSH 1 Infographic: A look at Donald Trump’s administration E-MAIL FACEBOOK TWITTER GOOGLE+ LINKEDIN 22 By Matt Rocheleau GLOBE STAFF DECEMBER 02, 2016 President-elect Donald Trump's administration Click each name for more details. Some positions require Senate confirmation. Positions left blank have not yet https://www.bostonglobe.com/news/politics/2016/12/02/infographic-look-donald-trump-administration/XJKzKNwAY2U3xg6HXufP2J/story.html[1/12/2017 9:12:16 PM] Infographic: A look at Donald Trump’s administration - The Boston Globe been filled. Last updated: Jan. 12. Title Name Known for Official Cabinet positions (in order of succession to the presidency) President Donald Trump Businessman Vice President Mike Pence Governor, Indiana Secretary of State Rex Tillerson Exxon Mobil CEO Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin Former Goldman Sachs executive Defense Secretary James Mattis Retired Marine general Attorney General Jeff Sessions U.S. Senator, Alabama Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke U.S. Representative, Montana Agriculture Secretary - - Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross Investor Labor Secretary Andrew Puzder Fast-food executive Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price U.S. Representative, Georgia Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson Retired neurosurgeon, presidential candidate Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao Former Labor secretary Energy Secretary Rick Perry Former Texas governor, presidential candidate Education Secretary Betsy DeVos Former chair Michigan Republican Party, education activist Veterans Affairs Secretary David Shulkin Physician, under secretary of Veterans Affairs Homeland Security Secretary John F. Kelly Retired Marine general "Cabinet-rank" positions Chief of Staff Reince Priebus RNC chairman EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt Oklahoma attorney general Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney U.S. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 163 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, APRIL 25, 2017 No. 70 House of Representatives The House met at noon and was Of course, understanding our system by emitting an unprecedented volume called to order by the Speaker pro tem- of government means understanding of hot air. pore (Mr. MESSER). the U.S. Constitution. It is the greatest Now, a week earlier we had tax day, f gift left to us by the Founders, and it and millions of Americans across this has stood the test of time. country, including in Los Angeles, DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO The success of the Constitution is needed to demonstrate to try to get TEMPORE due to its carefully designed system of Donald Trump to reveal his tax re- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- checks and balances. By separating the turns. Every President since Richard fore the House the following commu- powers of government into separate Nixon has released their tax returns. nication from the Speaker: but equal branches and guaranteeing Donald Trump told us in May of 2014: If WASHINGTON, DC, individual rights, the Constitution has I decide to run for office, I will produce April 25, 2017. been, as James Madison suggested, my tax returns. And he said it again a I hereby appoint the Honorable LUKE ‘‘the guardian of true liberty.’’ year later. And then he said it during MESSER to act as Speaker pro tempore on Mr. -

Washington Update

April 12, 2019 Washington Update This Week In Congress House – The House passed H.R. 1644, “The Save the Internet Act,” and H.R. 1331, “The Local Water Protection Act.” The House cancelled a vote on legislation to raise the defense and non-defense discretionary spending caps for Fiscal Years (FY) 2020 and 2021. Senate – The Senate confirmed David Bernhardt to be Secretary of the Department of the Interior, and Cheryl Marie Stanton to be Administrator of the Wage and Hour Division at the Department of Labor. Next Week In Congress House – The House will be in recess. Senate – The Senate will be in recess. TAX Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin On April 3, House Ways and Means Responds to Request for Trump’s Tax Committee Chairman Neal (D-MA) wrote to Returns Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Commissioner Charles Rettig requesting that the agency Key Points: provide six years of President Trump’s tax . Treasury Secretary Mnuchin tells House Ways returns along with the returns of eight and Means Chairman Neal (D-MA) that he businesses connected to President Trump. The is consulting with the Department of Justice on letter set an April 10 deadline for compliance how to respond to the request for President with the request. This week, on April 10, Trump’s tax returns. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin responded . On April 3, Chairman Neal wrote to IRS saying that Treasury is unable to meet the Commissioner Charles Rettig calling for the deadline and is still reviewing the request. past six years of tax returns for the President along with the returns of eight businesses Table of Contents connected to the Trump. -

September 10, 2020 the Honorable Steven Mnuchin Secretary U.S

September 10, 2020 The Honorable Steven Mnuchin Secretary U.S. Department of the Treasury 1500 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20220 Dear Secretary Mnuchin: I write to express concern regarding the potential acquisition of GNC Holdings Inc. (GNC) by Harbin Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd. (HPGC), a Chinese pharmaceutical company that describes itself as a “state-controlled Sino-foreign equity joint venture.” The ownership of an American health and nutrition company, with sensitive data on millions of customers and retail locations on and around military installations across the U.S., by a Chinese state-directed entity poses serious risks to U.S. national security. I therefore request a full review of this transaction by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). The Chinese government engages in persistent efforts to obtain a broad range of sensitive American personal data through illicit means such as state-sponsored theft from government agencies and private companies. The acquisition of a major health and nutrition chain with over 5,200 retail stores in the United States and an expansive customer base presents the opportunity for state-directed actors to purchase this information legally. Efforts to obtain personal and sensitive data related to health information and financial transactions of U.S. persons must be reviewed with an understanding of the malign foreign policy and intelligence aims of the Chinese government and Communist Party. The risk of espionage risk is further illustrated by information found on the official HPGC website that indicates the conglomerate has worked with the People’s Liberation Army under the auspices of the Communist Party’s military-civil fusion strategy. -

USTR Calendar

(b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b)(b) (6)(6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (5) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (5) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) (b) (6) June 2017 July 2017 June 18, 2017 SuMo TuWe Th Fr Sa SuMo TuWe Th Fr Sa 123 1 Sunday 45678910 2345678 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 9101112131415 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 25 26 27 28 29 30 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 SUNDAY Notes 18 From Jun 17 (b) (6) To Jun 26 7 AM 8 9 10 11 12 PM 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lighthizer, Robert E. EOP/USTR 1 8/9/2017 4:20 PM June 2017 July 2017 June 19, 2017 SuMo TuWe Th Fr Sa SuMo TuWe Th Fr Sa 123 1 Monday 45678910 2345678 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 9101112131415 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 25 26 27 28 29 30 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 MONDAY Notes 19 From Jun 17 (b) Out To Jun 26 (6) (b) (6) To Jun 23 7 AM 8 9 SENIOR STAFF MEETING; 203 WInder; FN-USTR-SCHEDULING 10 MEETING: Everett re Fin hearing 205 Winder 11 12 PM ARL 1 PRE BRIEF: Meeting with Minister Fox; 20 2 MEETING: Minister Fox (UK); 205 Winder 3 SCHEDULDING MEETING 4 MEETING: NAFTA with Melle 205 5 FN-USTR-SCHEDULING 6 Lighthizer, Robert E. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2017 Nominations Submitted to The

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2017 Nominations Submitted to the Senate December 22, 2017 The following list does not include promotions of members of the Uniformed Services, nominations to the Service Academies, or nominations of Foreign Service officers. Submitted January 20 Terry Branstad, of Iowa, to be Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the United States of America to the People's Republic of China. Benjamin S. Carson, Sr., of Florida, to be Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. Elaine L. Chao, of Kentucky, to be Secretary of Transportation. Jay Clayton, of New York, to be a Member of the Securities and Exchange Commission for a term expiring June 5, 2021, vice Daniel M. Gallagher, Jr. (term expired). Daniel Coats, of Indiana, to be Director of National Intelligence, vice James R. Clapper, Jr. Elisabeth Prince DeVos, of Michigan, to be Secretary of Education. David Friedman, of New York, to be Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the United States of America to Israel. Nikki R. Haley, of South Carolina, to be the Representative of the United States of America to the United Nations, with the rank and status of Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, and the Representative of the United States of America in the Security Council of the United Nations. Nikki R. Haley, of South Carolina, to be Representative of the United States of America to the Sessions of the General Assembly of the United Nations during her tenure of service as Representative of the United States of America to the United Nations. John F. Kelly, of Virginia, to be Secretary of Homeland Security. -

National Day of Prayer

GOD’S GUIDANCE STATE & LOCAL GOVERNMENT “...pray for kings and all who are in authority, in order that we Prayer has always been a foundation of our nation. may lead a tranquil and quiet life in all godliness and dignity.” NationalNational DayDay With one voice and mind, our forefathers united in –1Timothy 2:1,2 prayer for God’s guidance, protection and strength. Our founding fathers also called for prayer during the Great State of Texas 85th Legislative Session 2018 ofof PrayerPrayer Constitutional Convention. In their eyes, our recently Governor Greg Abbott created nation and freedoms were a direct gift from Lt Governor Dan Patrick God. Being a gift from God, there was only one way Attorney General Ken Paxton Speaker of the House Dennis Bonnen 68th Annual Observance to insure protection-through prayer. Senators & Representative For Christians, prayer is “communion with God.” Supreme Court Justices Pray for America - Love One Through prayer we experience relationship with God. Mayors, Councils, City & County Officials Another The quality of our prayer life then determines the Fire & Police Departments,Texas National Guard quality of our relationship with God. Prayer is talking School Authorities (public and private) “Love one another. Just as I have loved you.” with God. Prayer is listening to God. Prayer is enjoy- Find your legislator: www.fyi.legis.state.tx.us ing the presence of God. John 13:34 United States of America—Government It is our goal that you, your family and friends would President Donald Trump participate in the National Day of Prayer. We pray First Lady Melania Trump TEXAS PRAYER that the event impacts your life, and that praying for Vice President Mike Pence TEXAS PRAYER our nation moves from a one-day event to a lifetime Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney endeavor.