Interpreting Cultural Resources at Sesquicentennial State Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unali'yi Lodge

Unali’Yi Lodge 236 Table of Contents Letter for Our Lodge Chief ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Letter from the Editor ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Local Parks and Camping ...................................................................................................................................... 9 James Island County Park ............................................................................................................................................... 10 Palmetto Island County Park ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Wannamaker County Park ............................................................................................................................................. 13 South Carolina State Parks ................................................................................................................................. 14 Aiken State Park ................................................................................................................................................................. 15 Andrew Jackson State Park ........................................................................................................................................... -

Winter/Spring 2013-2014

FRESPACE Findings Winter/Spring 2013/2014 President’s Report water is a significant shock to our animals and is a hindrance to our equipment cleaning efforts 2013 has certainly been a year of change for us: during maintenance. Susan Spell, our long serving ParkWinter 2008 Allocated $78 for FRESPACE to become Manager, left us early in the year to be near an ill a non-profit member of the Edisto Chamber of family member. This had consumed much of her Commerce. The Board feels that the expense is time over the previous year or so. We will miss justified based on the additional publicity EBSP her. and FRESPACE will receive from the Chamber’s Our new Park Manager, Jon Greider, many advertising initiatives. joined us during the summer. He has been most The ELC water cooler no longer works. helpful to us and we look forward to working The failure occurred during the recent hard with him. freeze. When the required repair is identified Our Asst. Park Manager, Jimmy “Coach” FRESPACE is prepared to help defray the costs. Thompson, retired late in Dec. He has always Authorized up to $150 to install pickets been there to help us and we are going to miss around the ELC rain barrels. Currently the “Coach”. barrels are unsightly and in a very visible area. Our new Asst. Park Manager, Brandon Goff, assumed his new duties shortly after the Our Blowhard team recently was in need of first of 2014. additional volunteers. Ida Tipton sent out an email Dan McNamee, our Interpretive Ranger blast from Bill Andrews, our Blowhard Team lead, over the last several years, left us in the early fall describing our needs as well as describing what to go to work at the Low Country Institute. -

SOUTH CAROLINA Our Land, Our Water, Our Heritage

SOUTH CAROLINA Our Land, Our Water, Our Heritage LWCF Funded Places in LWCF Success in South Carolina South Carolina The Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) has provided funding to Federal Program help protect some of South Carolina’s most special places and ensure ACE Basin NWR recreational access for hunting, fishing and other outdoor activities. Cape Romain NWR South Carolina has received approximately $295 million in LWCF *Chattooga WSR funding over the past five decades, protecting places such as Fort Congaree NP Sumter National Monument, Cape Romain, Waccamaw and Ace Basin Cowpens NB National Wildlife Refuges, Congaree National Park, and Francis Marion Fort Sumter NM National Forest as well as sites protected under the Civil War Battlefield Francis Marion NF Preservation Program *Longleaf Pine Initiative Ninety Six NHS Sumter-Francis Marion NF Forest Legacy Program (FLP) grants are also funded under LWCF, to Sumter NF help protect working forests. The FLP cost-share funding supports Waccamaw NWR timber sector jobs and sustainable forest operations while enhancing wildlife habitat, water quality and recreation. For example, the FLP Federal Total $ 192,800,000 contributed to places such as the Catawba-Wateree Forest in Chester County and the Savannah River Corridor in Hampton County. The FLP Forest Legacy Program assists states and private forest owners to maintain working forest lands $ 39,400,000 through matching grants for permanent conservation easement and fee acquisitions, and has leveraged approximately $39 million in federal Habitat Conservation (Sec. 6) funds to invest in South Carolina’s forests, while protecting air and $ 1,700,000 water quality, wildlife habitat, access for recreation and other public American Battlefield Protection benefits provided by forests. -

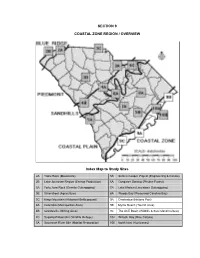

Coastal Zone Region / Overview

SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW Index Map to Study Sites 2A Table Rock (Mountains) 5B Santee Cooper Project (Engineering & Canals) 2B Lake Jocassee Region (Energy Production) 6A Congaree Swamp (Pristine Forest) 3A Forty Acre Rock (Granite Outcropping) 7A Lake Marion (Limestone Outcropping) 3B Silverstreet (Agriculture) 8A Woods Bay (Preserved Carolina Bay) 3C Kings Mountain (Historical Battleground) 9A Charleston (Historic Port) 4A Columbia (Metropolitan Area) 9B Myrtle Beach (Tourist Area) 4B Graniteville (Mining Area) 9C The ACE Basin (Wildlife & Sea Island Culture) 4C Sugarloaf Mountain (Wildlife Refuge) 10A Winyah Bay (Rice Culture) 5A Savannah River Site (Habitat Restoration) 10B North Inlet (Hurricanes) TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW - Index Map to Coastal Zone Overview Study Sites - Table of Contents for Section 9 - Power Thinking Activity - "Turtle Trot" - Performance Objectives - Background Information - Description of Landforms, Drainage Patterns, and Geologic Processes p. 9-2 . - Characteristic Landforms of the Coastal Zone p. 9-2 . - Geographic Features of Special Interest p. 9-3 . - Carolina Grand Strand p. 9-3 . - Santee Delta p. 9-4 . - Sea Islands - Influence of Topography on Historical Events and Cultural Trends p. 9-5 . - Coastal Zone Attracts Settlers p. 9-5 . - Native American Coastal Cultures p. 9-5 . - Early Spanish Settlements p. 9-5 . - Establishment of Santa Elena p. 9-6 . - Charles Towne: First British Settlement p. 9-6 . - Eliza Lucas Pinckney Introduces Indigo p. 9-7 . - figure 9-1 - "Map of Colonial Agriculture" p. 9-8 . - Pirates: A Coastal Zone Legacy p. 9-9 . - Charleston Under Siege During the Civil War p. 9-9 . - The Battle of Port Royal Sound p. -

2001 Report of Gifts (133 Pages) South Caroliniana Library--University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons University South Caroliniana Society - Annual South Caroliniana Library Report of Gifts 5-19-2001 2001 Report of Gifts (133 pages) South Caroliniana Library--University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/scs_anpgm Part of the Library and Information Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Publication Info 2001. University South Caroliniana Society. (2001). "2001 Report of Gifts." Columbia, SC: The ocS iety. This Newsletter is brought to you by the South Caroliniana Library at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University South Caroliniana Society - Annual Report of Gifts yb an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The The South Carolina South Caroliniana College Library Library 1840 1940 THE UNIVERSITY SOUTH CAROLINIANA SOCIETY SIXTY-FIFTH ANNUAL MEETING UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA Saturday, May 19, 2001 Dr. Allen H. Stokes, Jr., Secretary-Treasurer, Presiding Reception and Exhibit . .. 11 :00 a.m. South Caroliniana Library Luncheon 1:00 p.m. Clarion Townhouse Hotel Business Meeting Welcome Reports of the Executive Council and Secretary-Treasurer Address . Genevieve Chandler Peterkin 2001 Report of Gifts to the Library by Members of the Society Announced at the 65th Annual Meeting of the University South Caroliniana Society (the Friends of the Library) Annual Program 19 May 2001 South Carolina's Pivotal Decision for Disunion: Popular Mandate or Manipulated Verdict? – 2000 Keynote Address by William W. Freehling Gifts of Manuscript South Caroliniana Gifts to Modern Political Collections Gifts of Pictorial South Caroliniana Gifts of Printed South Caroliniana South Caroliniana Library (Columbia, SC) A special collection documenting all periods of South Carolina history. -

An Analysis of Landscapes of Surveillance on Rice Plantations in the Ace Basin, SC, 1800-1867 Sada Stewart Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2019 Plantations, Planning & Patterns: An Analysis of Landscapes of Surveillance on Rice Plantations in the Ace Basin, SC, 1800-1867 Sada Stewart Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Stewart, Sada, "Plantations, Planning & Patterns: An Analysis of Landscapes of Surveillance on Rice Plantations in the Ace Basin, SC, 1800-1867" (2019). All Theses. 3104. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/3104 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PLANTATIONS, PLANNING & PATTERNS: AN ANALYSIS OF LANDSCAPES OF SURVEILLANCE ON RICE PLANTATIONS IN THE ACE BASIN, SC, 1800-1867 A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Historic Preservation by Sada Stewart May 2019 Accepted by: Dr. Carter Hudgins, Committee Chair Dr. Barry Stiefel Amalia Leifeste Lauren Northup ABSTRACT This thesis explores patterns of the rice plantation landscape of the ACE River Basin in South Carolina during the period of 1800-1860 to assess how planters surveilled enslaved workers. The research consisted of a cartographic study of historic plats of nineteen rice plantations, a sample of the ninety-one plantations that covered the region during the height of rice production in South Carolina. For each of the plantations, the next level of analysis was viewshed and line of sight studies after 3D Sketch-Up models were created from each the plat. -

The Informal Courts of Public Opinion in Antebellum South Carolina, 54 S.C

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Florida Levin College of Law University of Florida Levin College of Law UF Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship Spring 2003 A Different Sort of Justice: The nforI mal Courts of Public Opinion in Antebellum South Carolina Elizabeth Dale University of Florida Levin College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub Part of the Legal History, Theory and Process Commons Recommended Citation Elizabeth Dale, A Different Sort of Justice: The Informal Courts of Public Opinion in Antebellum South Carolina, 54 S.C. L. Rev. 627 (2003), available at http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/400 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A DIFFERENT SORT OF JUSTICE: THE INFORMAL COURTS OF PUBLIC OPINION IN ANTEBELLUM SOUTH CAROLINA ELIZABETH DALE* I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 627 II. BACKGROUND: THE STANDARD ACCOUNT OF HONOR'S INFLUENCE ON CRIMINAL JUSTICE INANTEBELLUM SOUTH C AROLIN A .............................................................................. 630 A. Evidence of an Alternative Forum: Some Decisions by the Informal Court of Public Opinion .................................. -

National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER

NFS Form 10-900-b . 0MB Wo. 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service ,.*v Q21989^ National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing________________________________________ Historic Resources of South Carolina State Parks________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________________________ The Establishment and Development of South Carolina State Parks__________ C. Geographical Data The State of South Carolina [_JSee continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of gertifying official Date/ / Mary W. Ednonds, Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer, SC Dept. of Archives & His tory State or Federal agency and bureau I, heceby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for ewalua|ing selaled properties for listing in the National Register. Signature of the Keeper of the National Register Date E. -

Palmetto State's Memory, a History of the South Carolina Department of Archives & History 1905-1960

THE PALMETTO STATE’S MEMORY THE PA L M E T TO STATE’S MEMORY i A History of the South Carolina Department of Archives & History, 1905-1960 by Charles H. Lesser A HISTORY OF THE SCDAH, 1905-1960 © 2009 South Carolina Department of Archives & History 8301 Parklane Road Columbia, South Carolina 29223 http://scdah.sc.gov Book design by Tim Belshaw, SCDAH ii THE PALMETTO STATE’S MEMORY TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ................................................................................................................................................................... v Part I: The Salley Years ................................................................................................................................. 1 Beginnings ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Confederate and Revolutionary War Records and Documentary Editing in the Salley Years ........... 10 Salley vs. Blease and a Reorganized Commission ..................................................................................... 18 The World War Memorial Building ............................................................................................................ 21 A.S. Salley: A Beleaguered But Proud Man ............................................................................................... 25 Early Skirmishes in a Historical Battle ...................................................................................................... -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or

G3862 SOUTHERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3862 FEATURES, ETC. .C55 Clayton Aquifer .C6 Coasts .E8 Eutaw Aquifer .G8 Gulf Intracoastal Waterway .L6 Louisville and Nashville Railroad 525 G3867 SOUTHEASTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3867 FEATURES, ETC. .C5 Chattahoochee River .C8 Cumberland Gap National Historical Park .C85 Cumberland Mountains .F55 Floridan Aquifer .G8 Gulf Islands National Seashore .H5 Hiwassee River .J4 Jefferson National Forest .L5 Little Tennessee River .O8 Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail 526 G3872 SOUTHEAST ATLANTIC STATES. REGIONS, G3872 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .B6 Blue Ridge Mountains .C5 Chattooga River .C52 Chattooga River [wild & scenic river] .C6 Coasts .E4 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Area .N4 New River .S3 Sandhills 527 G3882 VIRGINIA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G3882 .A3 Accotink, Lake .A43 Alexanders Island .A44 Alexandria Canal .A46 Amelia Wildlife Management Area .A5 Anna, Lake .A62 Appomattox River .A64 Arlington Boulevard .A66 Arlington Estate .A68 Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial .A7 Arlington National Cemetery .A8 Ash-Lawn Highland .A85 Assawoman Island .A89 Asylum Creek .B3 Back Bay [VA & NC] .B33 Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge .B35 Baker Island .B37 Barbours Creek Wilderness .B38 Barboursville Basin [geologic basin] .B39 Barcroft, Lake .B395 Battery Cove .B4 Beach Creek .B43 Bear Creek Lake State Park .B44 Beech Forest .B454 Belle Isle [Lancaster County] .B455 Belle Isle [Richmond] .B458 Berkeley Island .B46 Berkeley Plantation .B53 Big Bethel Reservoir .B542 Big Island [Amherst County] .B543 Big Island [Bedford County] .B544 Big Island [Fluvanna County] .B545 Big Island [Gloucester County] .B547 Big Island [New Kent County] .B548 Big Island [Virginia Beach] .B55 Blackwater River .B56 Bluestone River [VA & WV] .B57 Bolling Island .B6 Booker T. -

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) T Constructed Sixteen State Parks Totalling 34,673 Acres in South Carolina

South Carolina Department of Archives and History Document Packet Number 4 THE CIVILIAN CONSERVATION CORPS IN SOUTH CAROLINA 1933–1942 South Carolina Department of Archives and History Document Packet Number 4 ©1997 South Carolina Department of Archives and History Produced by:The Education Service Area, Alexia J. Helsley, director; and the Publications Service Area, Judith M. Andrews, director. Credits: Folder drawings by Marshall Davis for the Camp Life Series, 1939–1940; Records of the Office of Education; Record Group 12; National Archives,Washington, DC Photographs of scenes from camp life courtesy South Carolina Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism, Columbia, SC Aerial photograph of Cheraw State Park: Can 20542, OY 4B 17; Records of the Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service; Records of the Department of Agriculture; Record Group 145; National Archives, Washington, DC Folder cover of CCC work on Hunting Island from Forestry Commission Administration Photographs from CCC files c1934–1942, SCDAH South Carolina Department of Archives and History Document Packet Number 4 Table of contents 7. Document 3: 13. Document 10: First enrolment form Pictograph report 1. Introductory folder Student activities Student activities 2. BSAP Objectives 8. Document 4: 14. Document 11: 3. Bibliography/Teacher resource Day telegram to state foresters Letter 4. Vocabulary Student activities Student activities 5. Document analysis worksheet 9. Document 5: 15. Document 12: Affidavit of property transfer Certificate 6. Photograph analysis worksheet Student activities Student activities 5. Document 1: 10. Document 6: 16. Document 13: FDR’s sketch of CCC Appproval of Project SP-1 1940 Census map Transcription Student activities Student activities Student activities 11. -

SOUTH CAROLINA Our Land, Our Water, Our Heritage

SOUTH CAROLINA Our Land, Our Water, Our Heritage LWCF Funded Places in LWCF Success in South Carolina South Carolina The Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) has provided funding to Federal Program help protect some of South Carolina’s most special places and ensure ACE Basin NWR Cape Romain NWR recreational access for hunting, fishing and other outdoor activities. *Chattooga WSR South Carolina has received approximately $303.5 million in LWCF Congaree NP funding over the past five decades, protecting places such as Fort Cowpens NB Sumter National Monument, Cape Romain, Waccamaw and Ace Basin Fort Sumter NM National Wildlife Refuges, Congaree National Park, and Francis Marion Francis Marion NF National Forest as well as sites protected under the Civil War Battlefield *Longleaf Pine Initiative Preservation Program Ninety Six NHS Sumter-Francis Marion NF Forest Legacy Program (FLP) grants are also funded under LWCF, to Sumter NF help protect working forests. The FLP cost-share funding supports Waccamaw NWR timber sector jobs and sustainable forest operations while enhancing Federal Total $ 196,300,000 wildlife habitat, water quality and recreation. For example, the FLP contributed to places such as the Catawba-Wateree Forest in Chester Forest Legacy Program County and the Savannah River Corridor in Hampton County. The FLP $ 39,400,000 assists states and private forest owners to maintain working forest lands through matching grants for permanent conservation easement and fee Habitat Conservation (Sec. 6) acquisitions, and has leveraged approximately $39 million in federal $ 1,700,000 funds to invest in South Carolina’s forests, while protecting air and water quality, wildlife habitat, access for recreation and other public American Battlefield Protection benefits provided by forests.