Upper Rangit Basin : Human Ecology of Eco-Tourism 259

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pelling Travel Guide - Page 1

Pelling Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/pelling page 1 Jul Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, Pelling When To umbrella. Max: Min: Rain: 297.0mm 12.10000038 11.39999961 Pelling, Sikkim is a marvellous little 1469727°C 8530273°C hill station, offering breathtaking VISIT Aug views of the Kanchenjunga http://www.ixigo.com/weather-in-pelling-lp-1178469 Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, mountain. Along with a breezy umbrella. atmosphere and unexpected Max: Min: 9.5°C Rain: 234.0mm Jan 18.39999961 8530273°C drizzles enough to attract the Famous For : HillHill StationNature / Very cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. WildlifePlaces To traveller, it also offers opportunity VisitCitMountain Max: Min: 3.0°C Rain: 15.0mm Sep 8.399999618 to see monasteries in the calm Very cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, 530273°C umbrella. countryside. Also serves as the Offering great views of the majestic Feb Max: Min: Rain: 294.0mm Himalayan mountains and specifically 11.60000038 9.300000190 starting point for treks in the Very cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. 1469727°C 734863°C Himalayas. Kanchenjunga, Pelling is essentially a laid Max: 6.0°C Min: Rain: 18.0mm back town of quiet monasteries. To soak in 2.400000095 Oct 3674316°C the tranquility of this atmosphere, one Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, Mar umbrella. should visit the Pemayansgtse Monastery Max: Min: Rain: 60.0mm and the Sangachoeling Monastery. Tourists Very cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. 13.80000019 10.80000019 Max: Min: Rain: 24.0mm 0734863°C 0734863°C also undertake excursions to the nearby 8.399999618 2.799999952 Sangay Waterfall and the Kchehepalri Lake 530273°C 316284°C Nov which is hidden in dense forest cover and is Apr Very cold weather. -

W & S Sikkim, Darjeeling & Bumchu Festival

Darjeeling & Sikkim plus Bumchu Fes6val – 10 days Jeep tour with Bumchu Buddhist Festival Tour JTT-SI-02: Delhi - Bagdogra – Kurseong – Darjeeling – Pelling – Kechopalri – Yuksom – Tashiding - Rumtek – Gangtok - Bagdogra – Delhi Activities & sights: Buddhist monastery festival, Darjeeling’s tea estates, Sikkim’s subtropical and alpine forests, Bhutia (‘Tibetan’) and Lepcha culture, Buddhist monasteries, Himalayan views, village culture, walks. Fixed dates: March 15 - 24, 2019 On this tour you’ll start at the tea capital of India, Darjeeling, and then travel up into the mountains of Sikkim. You’ll travel winding back roads that lead to quaint little villages, stay at homestays where you meet the Sikkimese up-close, but also at comfortable hotels and ‘ecoresorts’, and visit many Buddhist monasteries, including Pemayangtse, Rumtek and Tashiding. Highlight of the journey, no doubt, will be attending the Budddhist festival at Tashiding Gompa where monks will perform their traditional mask dances, enacting the victory of Buddhism over animism and good over evil. 1 Inerary Day 01: Delhi ✈ Bagdogra – Kurseong (41 km/ 1.5 hr) Early morning you’ll board the 2-hour flight from Delhi to Bagdogra (access is also possible form Kolkata). You will be met by our representative on arrival at Bagdogra airport and then driven to Kurseong, a drive of about 1.30 hrs. We check in at Cochrane Place, a hotel located on a ridge amidst lush tea gardens. Day 02: Kurseong – Darjeeling (31 km/ 1.5 hr) In the morning, we drive to Makaibari Tea Garden and visit the factory to see the manufacturing process of Darjeeling Tea. Later, we drive to Darjeeling. -

PERSPECTIVE OPEN ACCESS Assessment of Development Of

Chakraborty & Chakma. Space and Culture, India 2020, 7:4 Page | 133 https://doi.org/10.20896/saci.v7i4.532 PERSPECTIVE OPEN ACCESS Assessment of Development of Yuksom Gram Panchayat Unit in Sikkim using SWOT Model Sushmita Chakraborty†* and Dr Namita Chakma¥ Abstract SWOT model is a technique to appraise strategies for rural development. This study aims to apply this model to examine the development of Yuksom Gram Panchayat Unit (GPU) of West district of Sikkim, India. To accomplish this analysis, internal factor evaluation (IFE) matrix and external factor evaluation matrix (EFE) were prepared to identify the critical and less important factors for development. Finally, a framework for strategy has been formulated by linking ‘strength- opportunity’ (SO) and ‘weakness-threat’ (WT) aspects. Results show mountain environment sustainability as the most agreed one (SO) and on the other hand, implementation of ‘land bank scheme’ and microfinance (WT) as the alternate planning strategies for the development of the Yuksom area. Keywords: SWOT Analysis; ‘Land Bank Scheme’; Microfinance; Sikkim † Research Scholar, Department of Geography, The University of Burdwan, Purba Bardhaman, 713104, West Bengal *Email: [email protected] ¥ Associate Professor, Department of Geography, The University of Burdwan, Purba Bardhaman, 713104, West Bengal, Email: [email protected] Chakraborty & Chakma. Space and Culture, India 2020, 7:4 Page | 134 Introduction emphasis has been given to identifying the Development of a region is a multidimensional Strength, Weakness, Opportunity and Threat concept, and it is one of the debated and critical factors (SWOT) which affect development. The issues in socio-economic research (Milenkovic et study also tries to formulate an alternative al., 2014). -

2011 Sikkim Earthquake at Eastern Himalayas: Lessons Learnt from Performance of Structures

Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering 75 (2015) 121–129 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/soildyn Technical Note 2011 Sikkim Earthquake at Eastern Himalayas: Lessons learnt from performance of structures Sekhar Chandra Dutta a,n, Partha Sarathi Mukhopadhyay b, Rajib Saha c, Sanket Nayak a a Department of Civil Engineering, Indian School of Mines, Dhanbad 826004, Jharkhand, India b Department of Architecture, Town and Regional Planning, Indian Institute of Engineering Science and Technology, Shibpur, P. O. Botanic Garden, Howrah 711103, West Bengal, India c Civil Engineering Department, National Institute of Technology Agartala, Jirania 799046, Tripura(w), India article info abstract Article history: On 18 September 2011, all the Indian states and countries surrounding Sikkim witnessed a devastating Received 26 March 2015 moderate earthquake of magnitude 6.9 (Mw). Originating in Sikkim–Nepal border with an intensity of VIþ in Accepted 27 March 2015 MSK scale, this earthquake caused collapse of both unreinforced masonry buildings, heritage structures and framed structures followed by landslides and mud slides at various places of Sikkim. Significant damages have Keywords: been observed in relatively new framed structures mainly in Government buildings, thick masonry structures, Damage analysis while, the older wooden frame (ekra) non-engineered structures performed well during the earthquake. Out-of-plane rotation Further, it is noteworthy that government buildings suffered more than private ones and damages were Plastic hinge observed more in newer framed structures than older ones. Analysis of the damages identify lateral spreading Pounding of slope, pounding of buildings, out-of-plane rotation, generation of structural cracks, plastic hinge formation at Sikkim Earthquake column capitals and damage of infill wall material as predominant damage features. -

Up the Rathong Valley

NAVIGATE National Park The red panda is related to racoons as well as the more popular black-and- white pandas. They have bushy tails that grow up to 18 inches in length, which they wrap around their bodies for warmth in chilly weather. SBI Up the Rathong Valley EXPLORING THE KHANGCHENDZONGA NATIONAL PARK ON FOOT By SUJATHA PADMANABHAN AND ASHISH KOTHARI | Photographs by DHRITIMAN MUKHERJEE e stood transfixed, greedily We were in Khangchendzonga National untouched. The only way to explore the drinking in the beauty that lay Park (also spelled Kanchenjunga), slowly region is on foot. We had set out earlier before us. At our feet, was a making our way up the valley of the River that day from the village of Yuksom, after Wverdant valley with thick forests Rathong Chu. The sanctuary, which is a delicious breakfast of kodu (millet) clinging to its hillsides and a silvery river spread over 1,784 km in Sikkim, varies in parathas served with local honey. The snaking through its heart, the waters altitude from 2,000 to 8,585 m, creating a homely meal had been prepared by Dolma, dancing merrily over moss-covered diversity of habitats. Khangchendzonga’s the daughter-in-law of our homestay boulders. The warmth that the pristine rhododendron forests, high altitude host, who had cajoled us into having one view sparked within us was followed by lakes, and glacial slopes are a haven for more paratha, “one for the trek,” she said, a sobering thought: If it weren’t for an threatened animal and plant species, reminding us that it would be a few hours untiring campaign by local Buddhists and including the snow leopard and red panda. -

LACHEN GOMCHEN RINPOCHE Ngedup Chholing Lachen Monastery District Mangan P.O

LACHEN GOMCHEN RINPOCHE Ngedup Chholing Lachen Monastery District Mangan P.O. Lachen North Sikkim I would like to explain in short how Rathong Chu is connected with the four hundred and fifty three year old Bum Chu ceremony of Tashiding. In the very begining Gunr Padma Sambawa appeared miraculously accompanied by five main disciples. He blessed and confirmed this land as the most important hidden land of all the four hidden land all through Himalayas.He predicted that this land will provide refuge to all beings in future at the time when Tibet comes under danger. In the mid century, Rik Zin Goe Dem Pa visited this land. He reminded all the protecting deities of this land about the words given to them by Guru Padma Sambawa. He reaffirmed their commitment to further protect this hidden land. In 1600 as per prediction of Guru Rinpoche, four great saint gathered at Yuksam and opend the sacred land. They collected sample of earth and stones from all over this land and built a stupa called Tashi Odbar at Norbu Gang. Especially the great saint Lha Tsun Chenpo uncovered and affirmed all the sacred and holy siteslike the four main cavesin four direction of Tashiding. There are nine cave in between those four caves, and there are one hundred and eight smaller caves scattered around the nine caves. There are more than hundred foot print and hand printon rocks and stone throne belonging to Guru Rinpoche and the five disciples. Including eight Ye Dam Ka Gyat La Tso there are one hundred and nine La Tso (holy lakes). -

Bulletin of Tibetology

Bulletin of Tibetology VOLUME 41 NO. 2 NOVEMBER 2005 NAMGYAL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOLOGY GANGTOK, SIKKIM The Bulletin of Tibetology seeks to serve the specialist as well as the general reader with an interest in the field of study. The motif portraying the Stupa on the mountains suggests the dimensions of the field. Bulletin of Tibetology VOLUME 41 NO. 2 NOVEMBER 2005 NAMGYAL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOLOGY GANGTOK, SIKKIM Patron HIS EXCELLENCY V RAMA RAO, THE GOVERNOR OF SIKKIM Advisor TASHI DENSAPA, DIRECTOR NIT Editorial Board FRANZ-KARL EHRHARD ACHARYA SAMTEN GYATSO SAUL MULLARD BRIGITTE STEINMANN TASHI TSERING MARK TURIN ROBERTO VITALI Editor ANNA BALIKCI-DENJONGPA Assistant Editors TSULTSEM GYATSO ACHARYA VÉRÉNA OSSENT THUPTEN TENZING The Bulletin of Tibetology is published bi-annually by the Director, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, Gangtok, Sikkim. Annual subscription rates: South Asia, Rs150. Overseas, $20. Correspondence concerning bulletin subscriptions, changes of address, missing issues etc., to: Administrative Assistant, Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, Gangtok 737102, Sikkim, India ([email protected]). Editorial correspondence should be sent to the Editor at the same address. Submission guidelines. We welcome submission of articles on any subject of the history, language, art, culture and religion of the people of the Tibetan cultural area although we would particularly welcome articles focusing on Sikkim, Bhutan and the Eastern Himalayas. Articles should be in English or Tibetan, submitted by email or on CD along with a hard copy and should not exceed 5000 words in length. The views expressed in the Bulletin of Tibetology are those of the contributors alone and not the Namgyal Institute of Tibetology. -

Sikkim (Lepcha: Mayel Lyang; Limbu: Yuksom, One of the Fortified Place;[1

Sikkim (Lepcha: Mayel Lyang; Limbu: Yuksom, one of the fortified place;[1] Standard Tibetan: Tibetan: , bras ljongs; Denzong;[2] Demojongs; Nepali: འབས་ལོངས་ िसिकम (help·info), i.e. the Goodly Region, or Shikim, Shikimpati or Sikkim of the English and Indians…[3]) is a landlocked Indian state nestled in the Himalayas. This thumb-shaped state borders Nepal in the west, the Tibet Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China to the north and the east and Bhutan in the southeast. The Indian state of West Bengal borders Sikkim to its south.[4] With just slightly over 500,000 permanent residents, Sikkim is the least populous state in India and the second-smallest state after Goa.[5] Despite its small area of 7,096 km2 (2,740 sq mi), Sikkim is geographically diverse due to its location in the Himalayas. The climate ranges from subtropical to high alpine. Kangchenjunga, the world's third-highest peak, is located on the border of Sikkim with Nepal.[6] Sikkim is a popular tourist destination owing to its culture, scenic beauty and biodiversity. Legend has it that the Buddhist saint Guru Rinpoche visited Sikkim in the 9th century, introduced Buddhism and foretold the era of the monarchy. Indeed, the Namgyal dynasty was established in 1642. Over the next 150 years, the kingdom witnessed frequent raids and territorial losses to Nepalese invaders. It allied itself with the British rulers of India but was soon annexed by them. Later, Sikkim became a British protectorate and merged with India following a referendum in 1975. Sikkim has 11 official languages: Nepali (lingua franca), Bhutia, Lepcha (since 1977), Limbu (since 1981), Newari, Rai, Gurung, Mangar, Sherpa, Tamang (since 1995) and Sunwar (since 1996).[7] English is taught at schools and used in government documents. -

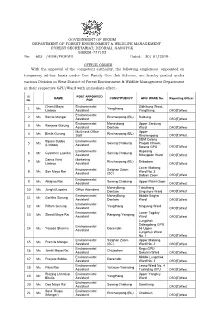

West District of Forest Environment & Wildlife Management Department in Their Respective GPU/Ward with Immediate Effect

GOVERNMENT OF SIKKIM DEPARTMENT OF FOREST ENVIRONMENT & WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT FOREST SECRETARIAT, DEORALI, GANGTOK SIKKIM-737102 No: 605 /ADM/FEWMD Dated: 30/ 01/2019 OFFICE ORDER With the approval of the competent authority, the following employees appointed on temporary ad-hoc basis under One Family One Job Scheme, are hereby posted under various Division in West District of Forest Environment & Wildlife Management Department in their respective GPU/Ward with immediate effect:- Sl. POST APPOINTED NAME CONSTITUENCY GPU/ WARD No. Reporting Officer No. FOR Chemi Maya Environmental Sidhibung Ward, 1 Ms Yangthang Limboo Assistant Yangthang DFO(T)West Environmental 2 Ms Sanita Mangar Rinchenpong (BL) Suldung Assistant DFO(T)West Environmental Maneybong Upper Sardung 3 Ms Ranjana Gurung Assistant Dentam Ward DFO(T)West Multi-task Office Upper Bimla Gurung Rinchenpong (BL) 4 Ms Staff Rinchenpong DFO(T)West SDM Colony Sipora Subba Environmental Soreng Chakung Pragati Chowk, 5 Ms (Limboo) Assistant Soreng GPU DFO(T)West Environmental Rupsang 6 Mr Gyalchen Lepcha Soreng Chakung Assistant Bitteygaon Ward DFO(T)West Dama Yanti Marketing 7 Mr Rinchenpong (BL) Sribadam Limboo Assistant DFO(T)West Lower Mabong Environmental Salghari Zoom San Maya Rai Ward No. 3 8 Ms Assistant (SC) Salbari Zoom DFO(T)West Environmental 9 Ms Alkajina Rai Soreng Chakung Upper Pakki Gaon Assistant DFO(T)West ManeyBong Takuthang Jungkit Lepcha Office Attendant 10 Ms Dentam Singshore Ward DFO(T)West Environmental ManeyBong Middle Begha 11 Mr Gorkha Gurung Assistant Dentam Ward DFO(T)West Environmental 12 Mr Pritam Gurung Yangthang Singyang Ward Assistant DFO(T)West Environmental Lower Togday 13 Ms Shanti Maya Rai Rangang Yangang Assistant Ward DFO(T)West Lungchok Salangdang GPU Environmental Yasoda Sharma Daramdin 58 Upper 14 Ms Assistant Lungchuk Ward No. -

Accepted List Candidates for 02 (Two) Vacant Posts of Civil Judge-Cum-Judicial Magistrate (Grade –Iii) in the Cadre of Sikkim Judicial Service

ACCEPTED LIST CANDIDATES FOR 02 (TWO) VACANT POSTS OF CIVIL JUDGE-CUM-JUDICIAL MAGISTRATE (GRADE –III) IN THE CADRE OF SIKKIM JUDICIAL SERVICE Sl. Name & Address of Correspondence Permanent Address, Phone No Numbers & . Email id 1 Abhishek Singh, Ganga Nagar, Siliguri, Darjeeling, C/o Shyam Kishore Singh, Near Ration West Bengal- 734005, Shop, Patiramjote, Matigara, M. No.: 9734177736 Darjeeling, West Bengal- 734010 [email protected] 2 Mr. Aditya Subba, Near Central Bank ATM, Near Central Bank ATM, Mirik Bazar, Darjeeling, Mirik Bazar, Darjeeling, West Bengal- 734214 West Bengal- 734214 M. No.: 8918588575 [email protected] 3 Ms. Aita Hangma Limboo, Tikjeck, Tikjeck, West Sikkim – 737111, West Sikkim - 737111 M. No.: 8670355901 [email protected] 4 Ms. Anu Lohar, Development Area, Development Area, C/0 Santosh Ration Shop, C/0 Santosh Ration Shop, New Puspa Garage, Gangtok- New Puspa Garage, Gangtok- 737101 737101, M. No.: 9560430462, [email protected] 5 Ms. Anusha Rai, Mirik Ward No. 3, Thana line, Mirik, Near Techno India Group Public Darjeeling, School, West Bengal- 734214 New Chamta, Sukna, Siliguri, M. No: 8447603441/7551014923 Darjeeling, West Bengal- 734009 anusharaiii/[email protected] 6 Ms. Aruna Chhetri, Upper Syari, Near Hotel Royal Plaza, Upper Syari, Gangtok, East Sikkim- 737101, Near Hotel Royal Plaza, M. No.: 7872969762 Gangtok, East Sikkim- 737101 [email protected] 7 Mr. Ashit Rai, Gumba Gaon, Sittong-II, Mahishmari, P.O- Champasari, P.O. Bagora, P.S. Kurseong- 734224, P.S. Pradhan Nagar, Dist: Darjelling, West Bengal. C/O- Khem Kr. Rai-734003, M. No.: Dist: Darjeeling, West Bengal. +918670758135/8759551258 [email protected] 8 Mr. -

Eliza Doherty 2013

THE ZIBBY GARNETT TRAVELLING FELLOWSHIP Report by Eliza Doherty Wall paintings conservation in Lachen Manilhakhang, North Sikkim, India 6 July – 6 September 2013 1 Photo on cover courtesy of Klara Peeters Contents Introduction 2 Study Trip 2 Sikkim 4 Tibet Heritage Fund 4 Lachen 5 The Manilhakhang 6 The Project 8 New Materials, New Techniques 9 Living in Lachen 16 Beyond Lachen: Thanggu, Gangtok and West Sikkim 18 Conclusion 21 Bibliography 24 2 Introduction My name is Eliza Doherty, I am twenty four years old and I have grown up in London. I am currently studying for the postgraduate diploma in conservation at City & Guilds of London Art School, which specialises in stone, stone related materials, wood and decorated surfaces. The three year course combines conservation practice with theory, and modules include laser cleaning, materials science, the theory of colour and polychromy, and microscopy of cross- sections and pigments. I completed my undergraduate degree in Art History and Philosophy at the University of St Andrews, during which I became increasingly interested in conservation. I have always loved making things, and after four years spent in the library I knew I wanted to go into something practical. A career in conservation seemed pretty perfect to me, for it would also encompass history, ethics and a deeper understanding of materials. Study Trip I was very fortunate to receive funding from the Zibby Garnett Travelling Fellowship (ZGTF), which I had seen publicised at City & Guilds, to participate in the conservation of the wall paintings in Lachen Manilhakhang, a Buddhist temple in North Sikkim, India. -

RESEARCH OPEN ACCESS Economy and Social Development of Rural Sikkim

Chakraborty and Chakma. Space and Culture, India 2016, 4:2 Page | 61 DOI: 10.20896/saci.v%vi%i.198 RESEARCH OPEN ACCESS Economy and Social Development of Rural Sikkim Sushmita Chakraborty†* and Namita ChakmaῙ Abstract The tiny Himalayan state of Sikkim is well known for its multi-cultural and multi-ethnic identity. There is a political and historical debate regarding the identity of communities in Sikkim. Lepchas are considered as original inhabitants of Sikkim. Currently, Lepcha, Bhutia and Limbu are recognised as minor communities and have Schedule Tribes (ST) status in the state. Individual community concentration is mainly found in North and West Sikkim. Lepcha-Bhutias are found mainly in North Sikkim whereas Limbus are concentrated in West Sikkim. Community concentration is profound in rural areas. Gyalshing sub-division of West Sikkim has been selected for the present study. Purpose of this study is to investigate the Gram Panchayat Unit (GPU) level economy and social development of the rural areas based mainly on secondary sources of information. A field survey was also conducted to interact with the local people. Findings suggest that education and population density are the key determinants for GPU level disparity in social development of the study area. It has been found that the economy is primarily agriculture based and fully organised by organic farming system. Recently, homestay (eco)tourism business has been started here like other parts of Sikkim. Key words: Himalaya, indigenous community, rural economy, organic farming, homestay (eco) tourism, social development, Sikkim, India †Research Scholar, Department of Geography, The University of Burdwan, Barddhaman, West Bengal, India, Email: [email protected] *Corresponding Author Ῑ Assistant Professor, Department of Geography, The University of Burdwan, Barddhaman, West Bengal, India, E-mail: [email protected] © 2016 Chakraborty and Chakma.