4D6f95592.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Work Completed on Shinjuku M-SQUARE, a New Shinjuku Station Area Landmark

March 9, 2018 For immediate release Mitsui Fudosan Co., Ltd. Work Completed on Shinjuku M-SQUARE, a New Shinjuku Station Area Landmark Tokyo, Japan, March 9, 2018 - Mitsui Fudosan Co., Ltd., a leading global real estate company headquartered in Tokyo, announced today that work finished January 31, 2018, on Shinjuku M-SQUARE, an office building project it had been working on in Shinjuku 3-Chome. Openings in this building are planned for Gucci Shinjuku on Friday, April 6, as well as for the Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation Shinjuku Branch, Shinjuku higashi Area Main Office, Shinjuku Corporate Business Office -Ⅰ,Shinjuku Corporate Business Office -Ⅱ and SMBC Nikko Securities Shinjuku-Higashiguchi Branch on Monday, May 21. Furthermore, the SMBC Trust Bank PRESTIA Shinjuku Higashiguchi Branch will open on Tuesday, July 17. This building is in an ideal location connected directly to Shinjuku Station on the Tokyo Metro Marunouchi Line and provides smooth access to all major lines, including various JR lines, via an underground passage. Equipped with pedestrian-flow plans to move from below ground to above ground, as well as elevators enabling barrier-free access, the building will be open from the day’s first train to its last, contributing to activating the flow of people in the Shinjuku area. The exterior of the building on Shinjuku-dori avenue has a completely glass façade and stylish design that make it stand out even in an area with many commercial buildings. Large digital signage has been installed in the exterior space on the second floor to be utilized as highly valuable advertising space. -

Huge City Model Communicates the Appeal of Tokyo -To Be Used by City in Presentation Given to IOC Evaluation Commission

Press Release 2009-04-17 Mori Building Co., Ltd. Mori Building provides support for Olympic and Paralympic bid Huge city model communicates the appeal of Tokyo -To be used by city in presentation given to IOC Evaluation Commission- At 17.0 m × 15.3 m, Japan's largest model With Tokyo making a bid to host the 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games, Mori Building is cooperating with the city by providing a huge model of central Tokyo for use in the upcoming tour of the IOC Evaluation Commission. This model was created with original technology developed by Mori Building; it is on display at Tokyo Big Sight. Created at 1/1000 scale, the model incorporates Olympic-related facilities that would be constructed in the city, and it presents a very appealing and sophisticated representation of near-future Tokyo. The model's 17.0 m × 15.3 m size makes it the largest in Japan, and its fine detail and high impact communicate a very real and attractive picture of Tokyo. On public view until April 30 In support of the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic bid, Mori Building is providing this city model as a tool that visually communicates the city's appeal in an easy-to-understand manner. From April 17 afternoon to 30, the model will be on display to the public in the Tokyo Big Sight entrance hall. We hope that many members of the general public will see it, and that it will further increase their interest in Tokyo. Mori Building independently created city model/CG pictures as a tool to facilitate an objective and panoramic comprehension of the city/landscape. -

01 the Expansion Of

The expansion of Edo I ntroduction With Tokugawa Ieyasu’s entry to Edo in 1590, development of In 1601, construction of the roads connecting Edo to regions the castle town was advanced. Among city construction projects around Japan began, and in 1604, Nihombashi was set as the undertaken since the establishment of the Edo Shogunate starting point of the roads. This was how the traffic network government in 1603 is the creation of urban land through between Edo and other regions, centering on the Gokaido (five The five major roads and post towns reclamation of the Toshimasusaki swale (currently the area from major roads of the Edo period), were built. Daimyo feudal lords Post towns were born along the five major roads of the Edo period, with post stations which provided lodgings and ex- Nihombashi Hamacho to Shimbashi) using soil generated by and middle- and lower-ranking samurai, hatamoto and gokenin, press messengers who transported goods. Naito-Shinjuku, Nihombashi Shinsen Edo meisho Nihon-bashi yukibare no zu (Famous Places in Edo, leveling the hillside of Kandayama. gathered in Edo, which grew as Japan’s center of politics, Shinagawa-shuku, Senju-shuku, and Itabashi-shuku were Newly Selected: Clear Weather after Snow at Nihombashi Bridge) From the collection of the the closest post towns to Edo, forming the general periphery National Diet Library. society, and culture. of Edo’s built-up area. Nihombashi, which was set as the origin of the five major roads (Tokaido, Koshu-kaido, Os- Prepared from Ino daizu saishikizu (Large Colored Map by hu-kaido, Nikko-kaido, Nakasendo), was bustling with people. -

Experience Japanese Culture Our Facilities and Investment in Updating the Ho- Tel’S Infrastructure

Timeline of facility AT A GLANCE Rikisaburo Kitajima and infrastructure Location General Manager improvements Just a stone’s throw from Tokyo’s most accessible transport hub, Shinjuku Station, To enhance the quality of our products and the Keio Plaza Hotel Tokyo is ideally located Pioneers in Asia services, we are committed to the renovation of for both business and sightseeing. Experience Japanese Culture our facilities and investment in updating the ho- tel’s infrastructure. From 2003–2009, the Keio As the first skyscraper hotel in the industry, creating and Plaza Hotel Tokyo spent more than 10 billion JR Yamanote Line Japan, we met the challenge of establishing new services and yen on a large-scale renovation project, while in the of Ikebukuro Heart Tokyo successfully constructing this introducing products, which still making significant advances in the hotel’s Asakusa Narita Airport kind of high-rise tower back include a dedicated Japanese restaurant business. We continue to invest in Ueno in 1971. During the first six sake bar, karaoke room, onsite renovation every year in order to maintain the months following the hotel’s wedding chapel, universal- level of sophistication in our design and to make opening, over one million designed guest rooms for the critical upgrades to the hotel’s functions. Tochomae people came to the top floor for physically challenged, and so Hachioji Chofu Shinjuku a view of the urban landscape much more. Akihabara from an unprecedented height. This spirit of discovery Keio Line The Keio Plaza Hotel Tokyo continues to define the legacy continues to be a pioneer in of the Keio Plaza Hotel Tokyo. -

Kogakuin-Uni Information 2018.Pdf

Message from the President Message from Message from the President Let Infinite Possibilities Bloom What do you think society seeks from future technicians and researchers? The answer is not apparent by merely looking at the present. That is because science and technology continue to advance. Having your own dreams is the first step that leads to society’s evolution. Please be sure to dream big. Even if your dreams aren’t realistic, that’s okay, since marvelous growth doubtless waits at the end of efforts to make your splendid dreams a reality. Society has long valued our alumni highly, particularly for their creativity. Our unique education process greatly affects those outcomes. Our role is to support your self-fulfillment by providing opportunities to understand the nature of things through hands-on experience, including project- based learning, working out tasks in practical ways, and encountering various phenomena through experiments and training. We also offer internships to acquaint technicians and researchers with the attributes that are needed, as well as club activities, student projects, and other extracurricular activities. Kogakuin University will continue growing together with students. Our goal is to provide core support for Japan as a scientific and technological nation by producing technicians and researchers who can solve problems through the power of science and technology. As specific measures toward that end, we established the School of Advanced Engineering in 2015—the first university in Japan to do so—and reorganized our Faculty of Informatics in 2016. This sort of expansion of studies into new regions is based on the spirit of artisanship that has been passed down since the university was founded. -

Ministry of the Environment

List of Public Service Corporations under the Jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Environment ●Public Service Corporations (selected) (As of April 2001) Name of the corporation Address of the main office Telephone number <Under supervision of the Minister’s Secretariat> Environmental Information Center 8F, Office Toranomon1Bldg., 1-5-8 Toranomon, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0001 03-3595-3992 Earth, Water and Green Foundation 6F, Nishi-shinbashi YK Bldg., 1-17-4 Nishi-shinbashi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0003 03-3503-7743 <Under supervision of the Waste Management and Recycling Department> Ecological Life and Culture Organization (ELCO) 6F, Sunrise Yamanishi Bldg., 1-20-10 Nishi-shinbashi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0003 03-5511-7331 Japan Environmental Sanitation Center 10-6 Yotsuya-kamicho, Kawasaki-ku, Kawasaki-shi, Kanagawa Prefecture 210-0828 044-288-4896 The National Federation of 4F, Daini-AB Bldg., 3-1-17 Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 106-0032 03-3224-0811 Industrial Waste Management Associations Japan Industrial Waste Technology Center 2F, Nihonbashi Koa Bldg., 2-8-4 Nihonbashi-horidomecho, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 103-0012 03-3668-6511 Japan Industrial Waste Management Foundation Sakura Shinbashi Bldg., 2-6-1 Shinbashi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0004 03-3500-0271 All Japan Private Sewerage Treatment Association 7F, Tokyo Yofuku Kaikan, 13 Ichigaya-hachimancho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-0844 03-3267-9757 Japan Education Center of Environmental Sanitation 2-23-3 Kikukawa, Sumida-ku, Tokyo 130-0024 03-3635-4880 Waste Water Treatment Equipment Engineer Center Kojimachi 4-chome Bldg., 4-3 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102-0083 03-3237-6591 Japan Sewage Works Association 1F, Nihon Bldg., 2-6-2 Otemachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-0004 03-5200-0811 Japan Waste Management Association 7F, IPB Ochanomizu, 3-3-11 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033 03-5804-6281 Japan Sewage Treatment Plant Operation and 5F, Sakura Bldg., 1-3-3 Uchikanda, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 101-0047 03-5281-9291 Maintenance Association, INC. -

Pecial Economic Zones of Metropolitan Tokyo Sby National Strategic Special Zone Team, Office of the Governor for Policy Planning, Tokyo Metropolitan Government

COVER STORY • “Amazing Tokyo” — Beyond 2020 • 2 pecial Economic Zones of Metropolitan Tokyo SBy National Strategic Special Zone Team, Office of the Governor for Policy Planning, Tokyo Metropolitan Government What Are the Special Economic Zones designated as the Tokyo Area National Strategic Special Zone by the of Metropolitan Tokyo? national government in May 2014 (Map). The zonal policy of the Tokyo Area National Strategic Special Zone Currently, there are two types of Special Economic Zones that the states that, “with the hosting of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Tokyo Metropolitan Government is working on. Paralympic Games, the Special Zones aim to attract capital, human The first is the Special Zone for Asian Headquarters which resources and companies to formulate an international business hub, received designation by the national government as one of the and also create new and internationally competitive businesses in Comprehensive Special Zones for International Competitiveness. such fields as drug development, through start-up companies and Amongst the many cities in Asia, Tokyo stands out as having rich innovation.” With this zonal policy in mind, the Tokyo Metropolitan resource potential in business, society, and culture. But the number Government is working to make Tokyo an open and global business of foreign companies has been sharply decreasing from its peak in city. 2005, and the Global Power City Index is showing that the gap between Tokyo and its rival foreign cities has been shrinking. Under Concrete Measures & Merits such circumstances, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government believes of Special Economic Zones that bringing foreign human resources, information, and capital to Tokyo, and hence providing for economic development, will be The Special Zone for Asian Headquarters provides merits such as pivotal for Japan’s revitalization. -

Experience and Track Record in Marunouchi

Otemachi Park Building, 1-1, Otemachi 1-chome, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-8133, Japan TEL +81-3-3287-5200 http://www.mec.co.jp/ Experience and Track Record in Marunouchi 1890 The construction of the area’s first modern office Building, Mitsubishi 1900 1890s – 1950s Ichigokan, was completed in 1894. Soon after, three-story redbrick office First Phase of Buildings began springing up, resulting in the area becoming known as the 1910 “London Block.” Development Following the opening of Tokyo Station in 1914, the area was further 1890s developed as a business center. American-style large reinforced concrete 1920 Dawning of a Full-Scale Buildings lined the streets. Along with the more functional look, the area Starting from Business Center Development was renamed the “New York Block.” Scratch 1940 Purchase of Marunouchi Land and Vision of a Major Business Center 1950 As Japan entered an era of heightened economic growth, there was a sharp 1960 1960s – 1980s increase in demand for office space. Through the Marunouchi remodeling plan that began in 1959, the area was rebuilt with large-scale office buildings, providing a considerable supply of highly integrated office space. 1970 Second Phase of Sixteen such buildings were constructed, increasing the total available floor Development space by more than five times. In addition, Naka-dori Avenue, stretching 1980 An Abundance of Large-Capacity from north to south through the Marunouchi area, was widened from 13 Office Buildings Reflecting a meters to 21 meters. The 1980s marked the appearance of high-rise buildings more than 100 The history of Tokyo’s Marunouchi 1990 Period of Rapid Economic Growth meters tall in the area. -

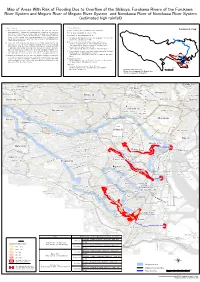

Map of Areas with Risk of Flooding Due to Overflow of the Shibuya

Map of Areas With Risk of Flooding Due to Overflow of the Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System (estimated high rainfall) 1. About this map 2. Basic information Location map (1) Pursuant to the provisions of the Flood Control Act, this map shows the (1) Map created by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government areas expected to flood and anticipated depth of inundation that can occur (2) Risk areas designated on June 27, 2019 when there is the level of rainfall used as a basis for flood control measures for sections subject to flood warnings of the Shibuya, Furukawa (3) Released as TMG announcement No.162 Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of Meguro River (4) Designation made based on Article 14, paragraph 2 of the Flood System and those subject to water-level notification of the Nomikawa River Control Act (Act No.193 of 1949) of Nomikawa River System. (5) River subject to flood warnings covered by this map (2) This river flood risk map uses a simulation to show inundation that can Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System occur due to overflow of the Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa Sumida River (The flood warning section is shown in the table below.) River System and Meguro River of Meguro River System and Nomikawa River Meguro River of Meguro River System of Nomikawa River System resulting from the level of rainfall used as a (The flood warning section is shown in the table below.) basis for flood control measures with an annual exceedance probability of 1 percent. -

Now(PDF:1427KB)

Okutama Minumadai- Okutama Town Shinsuikoen Ome City Yashio Ome IC Nishi- Ome Takashimadaira Adachi Tokorozawa Ward Wakoshi Daishi- Matsudo Okutama Lake Kiyose City Mae Rokucho Mizuho Town Shin- Akitsu Narimasu Akabane Akitsu Kita-Ayase Nishi-Arai Hakonegasaki Kanamachi Hamura Higashimurayama Itabashi Ward City Tama Lake Kita Ward Higashimurayama City Hikarigaoka Ayase Shibamata Higashiyamato Kumano- Kita- Higashikurume Oji Mae Senju Katsushika Hinode Town Musashimurayama City Nerima Ward Arakawa City Hibarigaoka Ward City Kamikitadai Shakujiikoen Kotakemukaihara Ward Keisei-Takasago Kodaira Toshimaen Toshima Aoto the changing Musashi-itsukaichi Hinode IC Fussa City Yokota Ogawa Nishitokyo City Ward Air Base Tamagawajosui Nerima Nishi- Tamagawajosui Kodaira City Tanashi Ikebukuro Nippori Akiruno City Ichikawa Tachikawa City Kamishakujii Nippori Haijima Bunkyo Taito Ward Akiruno IC Saginomiya Moto-Yawata Showa Kinen Ward face of tokyo Park Nakano Ward Takadanobaba Shin-Koiwa Kokubunji Koganei City Musashino City Ueno City Ogikubo Nakano Musashi-Sakai Mitaka Kichijoji Sumida Ward Akishima City Nishi-Kokubunji Nishi-Funabashi Kagurazaka Akihabara Kinshicho Hinohara Village Kokubunji Suginami Ward Tachikawa Kunitachi Nakanosakaue Shinjuku Ward Ojima Mitaka City Edogawa Ward City Kugayama Shinjuku Chiyoda Ward Sumiyoshi Hachioji-Nishi IC Honancho Fuchu City Akasaka Tokyo Funabori Tokyo, Japan’s capital and a driver of the global economy, is home Meiji Detached Fuchu Yoyogi- Shrine Hino City Chofu Airport Chitose- Meidai-Mae Palace Toyocho to 13 million people. The city is constantly changing as it moves Hachioji City Uehara Shinbashi Takahatafudo Fuchu- Karasuyama Shibuya Koto Ward Kasai Honmachi Shimotakaido steadily toward the future. The pace of urban development is also Keio-Hachioji Ward Urayasu Shimokitazawa Shibuya Chofu Kyodo Hamamatsucho Toyosu Yumenoshima accelerating as Tokyo prepares for the Olympic and Paralympic Hachioji Gotokuji Naka- Minato Chuo Park Kitano Hachioji JCT Tama Zoological Seijogakuen- Meguro Ward Ward Games in 2020 and beyond. -

Shinjuku Rules of Play

Shinjuku Rules of Play Gary Kacmarcik Version 2 r8 Tokyo is a city of trains and Shinjuku is the busiest In Shinjuku, you manage one of these con- train station in the world. glomerates. You need to build Stores for the Customers to visit while also constructing the rail Unlike most passenger rail systems, Tokyo has lines to get them there. dozens of companies that run competing rail lines rather than having a single entity that manages rail Every turn, new Customers arrive looking to for the entire city. Many of these companies are purchase a specific good. If you have a path to a large conglomerates that own not only the rail, but Store that sells the goods they want, then you also the major Department Stores at the rail might be able to move those new Customers to stations. your Store and work toward acquiring the most diverse collection of Customers. Shinjuku station (in Shinjuku Ward) expands down into Yoyogi station in Shibuya Ward. A direct rail connection exists between these 2 stations that can be used by any player. Only Stores opened in stations with this Sakura icon may be upgraded to a Department Store. Department Store Upgrade Bonus tokens are placed here. The numbers indicate the total number of customers in the Queue (initially: 2). Customer Queue New Customers will arrive on the map from here. Stations are connected by lines showing potential Components future connections. These lines cannot be used until a player uses theE XPAND action to place track Summary on them, turning them into a rail connection. -

Hilton Tokyo the Facts

HILTON TOKYO THE FACTS Hilton Tokyo is located in Shinjuku, the heart of Tokyo's business, shopping and AT A GLANCE entertainment district and is an ideal place to experience modern Japan. Directly • Central location in the heart of Tokyo connected to the Tokyo Metro subway, the hotel is conveniently located to • Fully refurbished guest rooms and exclusive Harajuku, Ginza, Akihabara and the famous Tokyo Skytree. Relax in one of the 811 Executive Lounge modern Japanese style rooms and suites, and admire stunning city views. Dine at • Stylish meeting and function spaces with a maximum capacity of 1,200 people one of 6 restaurants and bars including TSUNOHAZU – a new open plan concept • 24-hour Fitness Center with swimming pool dining floor like no other in Tokyo. Host a meeting or event at one of Hilton Tokyo’s • 6 restaurants and bars, including TSUNOHAZU - a new open plan concept dining floor like no 20 modern and flexible meeting and function rooms accommodating up to 1,200 other in Tokyo guests or catchup on some work at the fully equipped business center. Or simply • 24-hour Business Center rejuvenate during your stay with access to the indoor pool and spa facilities, or • Multilingual Team Members enjoy a game of tennis or workout in the 24-hour fitness center. OUR ROOMS OUR FACILITIES GUEST ROOM EXECUTIVE LOUNGE Enjoy fine views while staying at the hotel, where Start the day with a complimentary breakfast at rooms facing the east showcase panoramas of the Executive Lounge, relax with afternoon tea or city skyscrapers, while options on the west side enjoy cocktails in the evening, while admiring the offer stunning scenes of Mt.