Semi-Natural Grassland Survey of Counties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fyffes Decision

LAW SOCIETY GazetteGazette€3.75 June 2008 NONO MOREMORE MONKEYMONKEY BUSINESS:BUSINESS: TheThe FyffesFyffes decisiondecision INSIDE: LISBON – PRO AND CON • LYNN STRUCK OFF • CONFESSIONS OF A CRIMINAL MIND • NERVOUS SHOCK , - , -9 iÞÊvi>ÌÕÀià ÌiÌÊ>`Ê ÛiÀ>}i UÊÊnÊV>ÃiÊÀi«ÀÌ}Ê>`Ê`}iÃÌÊÃiÀiÃ]ÊVÕ`}ÊÌ iÊ ÀiÜi`Ê,Ê>`Ê/,]Ê}Û}ÊÞÕÊvÕÊÌiÝÌÊ>ÜÊÊ Ài«ÀÌÃÊ`>Ì}ÊL>VÊÌÊ£nÈÇI 7iÃÌ>ÜÊ ÊÃÊÌ iÊÃÌÊ UÊÊÊV«iÌiÊÃiÌÊvÊVÃ`>Ìi`ÊVÌÃÊ>`Ê-°°ÃÊvÀÊ>Ê iÞÊ>Ài>ÃÊvÊ>Ü V«Ài iÃÛiÊ>`Ê UÊÊ Ý«iÀÌÊ>>ÞÃÃÊvÊvÕÊÌiÝÌÊVÌÃÊL>VÊÌÊ£n{ UÊÊ£äÊÕÀ>ÊÃiÀiÃ]ÊVÛiÀ}ÊiÛiÀÞÊÌ«VÊÞÕÊÜÕ`Êii`Ê >ÕÌ ÀÌ>ÌÛiÊÀà Êi}>Ê ÌÊÀiÃi>ÀV UÊÊ,iiÛ>ÌÊiÜÃÊ>`ÊLÕÃiÃÃÊvÀ>Ì vÀ>ÌÊÃiÀÛVi°Ê UÊÊ ÕÀÀiÌÊ>Ü>ÀiiÃÃÊÃiÀÛViÊÕ«`>Ìi`ÊViÊ>Ê`>Þ ÕVÌ>ÌÞ UÊÊ*ÜiÀvÕÊÃi>ÀV ÊvÕVÌ>ÌÞ UÊÊi}>ÞʵÕ>wÊi`ÊVÕÃÌiÀÊÃÕ««ÀÌÊÌi> UÊÊÌÀ>iÌÊÃÕÌÃÊvÀÊVÕÃÌÃi`ÊÜi`}iÊÊ >>}iiÌÊÃÞÃÌià IÊÊ/,ÊÀà Ê>ÜÊ/iÃÊ,i«ÀÌîÊÜÊLiÊ>``i`Ê `ÕÀ}ÊÓään LAW SOCIETY GAZETTE JUNE 2008 CONTENTS On the cover LAW SOCIETY Insider trading used to be the golden cow from which executives amassed fortunes at the expense of the market. But surely that’s Gazette just bananas! June 2008 PIC: GETTY IMAGES Volume 102, number 5 Subscriptions: €57 REGULARS 5 President’s message 7 News Analysis 12 12 News feature: Law Society’s objections to DPP’s ‘reasons’ proposals 14 News feature: you guessed it: more collaborative law! Comment 16 16 Viewpoint: two opinions, one vote – at least until Lisbon II: the re-run 11 40 People and places 47 Student spotlight 48 Parchment ceremony photographs Book reviews 55 Literature, Judges and the Law; Practice and Procedure in the Superior Courts; Company Law Compliance and Enforcement Briefing 57 57 Council report 58 Legislation update: 16 April – 20 May 2008 60 Solicitors Disciplinary Tribunal 61 Practice note 16 62 Firstlaw update 64 Eurlegal: public procurement, helicopter gunships? Wow! 68 Professional notices 73 Recruitment advertising Editor: Mark McDermott. -

The Analysis of the Flora of the Po@Ega Valley and the Surrounding Mountains

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE NAT. CROAT. VOL. 7 No 3 227¿274 ZAGREB September 30, 1998 ISSN 1330¿0520 UDK 581.93(497.5/1–18) THE ANALYSIS OF THE FLORA OF THE PO@EGA VALLEY AND THE SURROUNDING MOUNTAINS MIRKO TOMA[EVI] Dr. Vlatka Ma~eka 9, 34000 Po`ega, Croatia Toma{evi} M.: The analysis of the flora of the Po`ega Valley and the surrounding moun- tains, Nat. Croat., Vol. 7, No. 3., 227¿274, 1998, Zagreb Researching the vascular flora of the Po`ega Valley and the surrounding mountains, alto- gether 1467 plant taxa were recorded. An analysis was made of which floral elements particular plant taxa belonged to, as well as an analysis of the life forms. In the vegetation cover of this area plants of the Eurasian floral element as well as European plants represent the major propor- tion. This shows that in the phytogeographical aspect this area belongs to the Eurosiberian- Northamerican region. According to life forms, vascular plants are distributed in the following numbers: H=650, T=355, G=148, P=209, Ch=70, Hy=33. Key words: analysis of flora, floral elements, life forms, the Po`ega Valley, Croatia Toma{evi} M.: Analiza flore Po`e{ke kotline i okolnoga gorja, Nat. Croat., Vol. 7, No. 3., 227¿274, 1998, Zagreb Istra`ivanjem vaskularne flore Po`e{ke kotline i okolnoga gorja ukupno je zabilje`eno i utvr|eno 1467 biljnih svojti. Izvr{ena je analiza pripadnosti pojedinih biljnih svojti odre|enim flornim elementima, te analiza `ivotnih oblika. -

Polling Offaly

CONSTITUENCY OF OFFALY NOTICE OF POLLING STATIONS EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, LOCAL ELECTIONS AND REFERENDUM ON THIRTY-EIGHTH AMENDMENT OF THE CONSTITUTION BILL 2016 To be held on Friday the 24th day of MAY 2019 between the hours of 07.00 a.m. and 10.00 p.m. I, THE UNDERSIGNED, BEING THE EUROPEAN LOCAL RETURNING OFFICER FOR THE CONSTITUENCY OF OFFALY, HEREBY GIVE NOTICE THAT THE POLLING STATIONS LISTED BELOW, FOR THE COUNTY OF OFFALY AND THE DESCRIPTION OF ELECTORS ENTITLED TO VOTE AT EACH STATION IS AS FOLLOWS: VOTERS ENTITLED POLLING POLLING TO VOTE AT EACH POLLING STATION TOWNLANDS AND/OR STREETS STATION DISTRICT PLACE, NUMBERS NO. ON REGISTER Crinkle National School BIRR RURAL (Pt. of): Ballindarra (Riverstown), Ballinree (Fortal), 1 BIRR RURAL Beech Park, Boherboy, Cemetery Road, Clonbrone, Clonoghill 1 - 556 No. 1 Lower, Clonoghill Upper, Coolnagrower, Cribben Terrace, Cypress B.1 Grove, Derrinduff, Ely Place, Grove Street, Hawthorn Drive, Leinster Villas BIRR RURAL (Pt. of): Main Street Crinkle, Millbrook Park, Military 2 Crinkle National School BIRR RURAL 557 - 1097 No. 2 Road, Roscrea Road, School Street, Swag Street, The Rocks. B.1 KILCOLMAN (Pt. of): Ballegan, Ballygaddy, Boheerdeel, Clonkelly, Lisduff, Rathbeg, Southgate. 3 Oxmanstown National BIRR RURAL BIRR RURAL (Pt. of): Ballindown, Ballywillian, Lisheen, Woodfield 1098 - 1191 School, Birr No. 1 or Tullynisk. B.1 4 Civic Offices, Birr No. 1 BIRR URBAN: Brendan Street, Bridge Street, Castle Court, Castle BIRR URBAN Mall, Castle Street, Castle St. Apartments, Chapel Lane, Church 1 - 600 Street, Community Nursing Unit, Connaught Street, Cornmarket B.2 Apartments, Cornmarket Street, Emmet Court, Emmet Square, Emmet Street, High Street, Main Street, Main Street Court, Mill Street, Mineral Water Court, Mount Sally, Oxmantown Mall, Post Office Lane, Rosse Row, St. -

Roscommon Swift Survey 2020

Roscommon Swift Survey 2020 A report by John Meade and Ricky Whelan A project funded by Roscommon County Council and the Department of Culture Heritage and the Gaeltacht Contents 1 Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 6 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 8 3 Project Objectives ......................................................................................................................... 10 4 Methodology ................................................................................................................................. 10 5 Data Collection .............................................................................................................................. 12 6 Citizen Science .............................................................................................................................. 12 7 Results ........................................................................................................................................... 13 7.1 Survey Visits .......................................................................................................................... 14 7.2 Swift Nests ............................................................................................................................ 16 8 Site Based Results ........................................................................................................................ -

Poaceae: Pooideae) Based on Phylogenetic Evidence Pilar Catalán Universidad De Zaragoza, Huesca, Spain

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 31 2007 A Systematic Approach to Subtribe Loliinae (Poaceae: Pooideae) Based on Phylogenetic Evidence Pilar Catalán Universidad de Zaragoza, Huesca, Spain Pedro Torrecilla Universidad Central de Venezuela, Maracay, Venezuela José A. López-Rodríguez Universidad de Zaragoza, Huesca, Spain Jochen Müller Friedrich-Schiller-Universität, Jena, Germany Clive A. Stace University of Leicester, Leicester, UK Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Catalán, Pilar; Torrecilla, Pedro; López-Rodríguez, José A.; Müller, Jochen; and Stace, Clive A. (2007) "A Systematic Approach to Subtribe Loliinae (Poaceae: Pooideae) Based on Phylogenetic Evidence," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 23: Iss. 1, Article 31. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol23/iss1/31 Aliso 23, pp. 380–405 ᭧ 2007, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden A SYSTEMATIC APPROACH TO SUBTRIBE LOLIINAE (POACEAE: POOIDEAE) BASED ON PHYLOGENETIC EVIDENCE PILAR CATALA´ N,1,6 PEDRO TORRECILLA,2 JOSE´ A. LO´ PEZ-RODR´ıGUEZ,1,3 JOCHEN MU¨ LLER,4 AND CLIVE A. STACE5 1Departamento de Agricultura, Universidad de Zaragoza, Escuela Polite´cnica Superior de Huesca, Ctra. Cuarte km 1, Huesca 22071, Spain; 2Ca´tedra de Bota´nica Sistema´tica, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Avenida El Limo´n s. n., Apartado Postal 4579, 456323 Maracay, Estado de Aragua, -

Anacamptis Morio) at Upwood Meadows NNR, Huntingdonshire

British & Irish Botany 1(2): 107-116, 2019 Long-term monitoring of Green-winged Orchid (Anacamptis morio) at Upwood Meadows NNR, Huntingdonshire Peter A. Stroh* Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland, Cambridge University Botanic Garden, 1 Brookside, Cambridge CB2 1JE, UK *Corresponding author: Peter Stroh: [email protected] This pdf constitutes the Version of Record published on 21st May 2019 Abstract The results of monitoring a population of Anacamptis morio over a 40-year period (1978-2017) in a permanent plot at Upwood Meadows NNR, Huntingdonshire, are presented. Flowering and vegetative plants were recorded each year, with individuals relocated using phenomarkers and triangulation. The majority of plants flowered for over half of their lifespan, the average lifespan of an individual plant was almost 10 years, and the known maximum lifespan above-ground for an individual was at least 36 years. The average age of the cohort became much younger over the course of the study, with potential reasons given including extreme old age, a lack of recruitment, and climate. Key words: demography; fixed plot; recruitment; mortality; triangulation Introduction In 1962 Terry Wells became the Nature Conservancy’s first grassland ecologist, based at Monks Wood, Huntingdonshire. In his first three years at the Research Station he set up a number of long-term monitoring projects, mainly across the chalk and limestone of southern England, designed to study the dynamics of British orchids and changes to associated vegetation. One of the first of these studies, set up in the early 1960s, followed the fate of a cohort of Autumn Lady’s Tresses (Spiranthes spiralis) at Knocking Hoe in Bedfordshire. -

Language Notes on Baronies of Ireland 1821-1891

Database of Irish Historical Statistics - Language Notes 1 Language Notes on Language (Barony) From the census of 1851 onwards information was sought on those who spoke Irish only and those bi-lingual. However the presentation of language data changes from one census to the next between 1851 and 1871 but thereafter remains the same (1871-1891). Spatial Unit Table Name Barony lang51_bar Barony lang61_bar Barony lang71_91_bar County lang01_11_cou Barony geog_id (spatial code book) County county_id (spatial code book) Notes on Baronies of Ireland 1821-1891 Baronies are sub-division of counties their administrative boundaries being fixed by the Act 6 Geo. IV., c 99. Their origins pre-date this act, they were used in the assessments of local taxation under the Grand Juries. Over time many were split into smaller units and a few were amalgamated. Townlands and parishes - smaller units - were detached from one barony and allocated to an adjoining one at vaious intervals. This the size of many baronines changed, albiet not substantially. Furthermore, reclamation of sea and loughs expanded the land mass of Ireland, consequently between 1851 and 1861 Ireland increased its size by 9,433 acres. The census Commissioners used Barony units for organising the census data from 1821 to 1891. These notes are to guide the user through these changes. From the census of 1871 to 1891 the number of subjects enumerated at this level decreased In addition, city and large town data are also included in many of the barony tables. These are : The list of cities and towns is a follows: Dublin City Kilkenny City Drogheda Town* Cork City Limerick City Waterford City Database of Irish Historical Statistics - Language Notes 2 Belfast Town/City (Co. -

Please Click Here to Read the Project Repor

Counties Longford & Roscommon Wetland Study Wetland Surveys Ireland 2017 _______________________________________________________________ Authors: Foss, P.J., Crushell, P. & Gallagher, M.C. (2017) Title: Counties Longford & Roscommon Wetland Study. Report prepared for Lonford and Roscommon County Councils. An Action of the County Longford Draft Heritage Plan 2015-2020 & the County Roscommon Heritage Plan 2012-2016 Copyright Longford & Roscommon County Councils 2017 Wetland Surveys Ireland Dr Peter Foss Dr Patrick Crushell 33 Bancroft Park Bell Height Tallaght Kenmare Dublin 24 Co Kerry [email protected] [email protected] All rights reserved. No Part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of Longford & Roscommon County Councils. Views contained in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of Longford & Roscommon County Councils. Photographic Plate Credits All photographs by Peter Foss & Patrick Crushell 2017 unless otherwise stated. Copyright Longford & Roscommon County Councils. Report cover images: Derreenasoo Bog, Co. Roscommon (Photo: P. Foss) Counties Longford & Roscommon Wetland Study Wetland Surveys Ireland 2017 ____________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................ -

A Gazetteer of Castles in County Offaly Ballindarra

BALLINDARRA A GAZETTEER OF CASTLES – Béal Átha na Darach (THE FORD-MOUTH OF THE OAK) NGR: 205309/203554 SMR NO. OFO35-021---- IN COUNTY OFFALY BARONY: Ballybritt TERRITORY: O’CARROLL’S COUNTRY [ÉILE UÍ CHEARBHAILL / ELY O’CARROLL] BY CAIMIN O’BRIEN CIVIL PARISH: Birr 17TH CENTURY PARISH: Birr BALLINDARRA CASTLE Location of Ballindarra Castle in Offaly and the surrounding counties A GAZETTEER OF CASTLES IN COUNTY OFFALY BALLINDARRA SUMMARY Today a modern bungalow stands inside the area of the bawn of the levelled O’Carroll castle. The castle was situated beside the medieval routeway connecting the medieval castles of Nenagh and Birr. It was strategically located to guard and control the fording point and bridge over the Little Brosna River which was the gateway to O’Carroll’s Country from the neighbouring lands of Ormond and the Gaelic territory of the O’Kennedys which now forms part of North Tipperary. Ballindarra Castle was a multi-storeyed tower house probably built in the late 15th or early 16th century by the O’Carrolls and was defended by a polygonal- shaped bawn wall. A short section of the upstanding wall, running parallel to the eastern bank of the river, may belong to the original bawn wall. Drawing c.1800, of Ballindarra Castle and Bawn from the Birr Castle archives (A/24) inspired by an account of the 1690 Siege of Birr. This drawing is an artist’s impression of a three storey roofless tower house standing inside an irregular-shaped bawn. It stands guarding the important pass or crossing point over the Little Brosna River which connected the medieval castles of Nenagh and Birr. -

The Coonans of Roscrea by Michael F

The Coonans of Roscrea By Michael F. McGraw, Ph.D. [email protected] October 26, 2018 Introduction This continues the effort to organize, consolidate and extend the research of Robert Conan. The following paper concerns the Coonan families found in the area of Ireland around Roscrea, Co. Tipperary. The material found in Conan’s notes pertaining to this subject consists of two parts: (1) a structured family report covering five generations and (2) a set of interviews conducted by Robert Conan in Ireland in 1970 and 1972. The data in the structured family report covers the period from the mid-1700s to the early 1800s and is discussed in Part I of this paper. Information was also found on a Roscrea family which had immigrated to Australia in 1865; they are also included in this part of the paper. The Robert Conan interviews covered the then current generation of Coonan descendants and went back one or two generations and which forms Part II of the paper. The overall goal is to connect the earlier Coonan generations with the more recent descendants, where possible. As many church and civil records as possible were collected to complement those collected by Robert Conan during his visits to Ireland. The information has been structured as family trees to achieve a concentration of the information and to increase the probability of discovering other family connections. The geographic proximity of the families described in this paper holds the promise of finding connections among them. A more long range goal is to find connections with the Upperchurch Coonan families, which were described in an earlier paper. -

January 1 to December 31, 195 8 259 250956. Cynosurus

JANUARY 1 TO DECEMBER 31, 195 8 259 250956. CYNOSURUS CRISTATUS L. Poaceae. Crested dogtail. Col. No. 17215. Mavrosko Lake, Macedonia. Elevation 4,200 feet. Sparse, tufted grass. 250957 to 250959. DACTYLIS GLOMERATA L. Poaceae. Orchardgrass. 250957. Col. No. 17218. Mavrosko Lake, Macedonia. 250958. Col. No. 17234. Dry, rocky sandstone slope, Lake Ohrid, Macedonia. Elevation 2,500 feet. Xerophyte; leaves scanty. 250959. Col. No. 17224. Mavrosko Lake, Macedonia. Elevation 4,200 feet. Thickly tufted perennial. 250960. DACTYLIS HISPANICA Roth. Col. No. 17352. Arid limestone slope, south of Split, Dalmatia. Elevation 500 feet. Sparse, narrow-leaved perennial. 250961. DESCHAMPSIA sp. Poaceae. Col. No. 17336. Nichsich, Montenegro. Elevation 2,100 feet. Narrow- leaved and fescuelike perennial, said to be palatable to livestock. 250962. DESCHAMPSIA sp. Col. No. 17360. Kupres Valley, Bosnia. Elevation 3,800 feet. Long culm, sod-forming perennial; well liked by livestock. 250963. FESTUCA ARUNDINACEA Schreb. Poaceae. Tall fescue. Col. No. 17174. Skopje, Macedonia. Elevation 1,000 feet. Vigorous peren- nial ; leaves soft, large, palatable. 250964. FESTUCA ELATIOR L. Meadow fescue. Col. No. 17201. Sloping meadow, Mavrosko Lake, Macedonia. Elevation 4,200 feet. Thriving perennial; palatable. 250965. FESTUCA sp. Col. No. 17207. Meadow slope, Mavrosko Lake, Macedonia. Densely tufted perennial, seeding freely. 250966. FESTUCA RUBRA L. Red fescue- Col. No. 17294. Fifty km. east of Titograd, Montenegro. Elevation 4,200 feet. Fine-leaved perennial. 250967. FESTUCA OVINA L. Sheep fescue. Col. No. 17225. West of Mavrosko Lake, Macedonia. Elevation 3,500 feet. Shade-tolerant, fine-leaved perennial; leaves numerous, short. 250968. HORDEUM VULGARE L. Poaceae. Common barley. Col. No. 17241. -

Grid Export Data

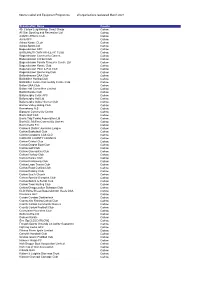

Sports Capital and Equipment Programme all organisations registered March 2021 Organisation Name County 4th Carlow Leighlinbrige Scout Group Carlow All Star Sporting and Recreation Ltd Carlow Ardattin Athletic Club Carlow Asca GFC Carlow Askea Karate CLub Carlow Askea Sports Ltd Carlow Bagenalstown AFC Carlow BAGENALSTOWN ATHLETIC CLUB Carlow Bagenalstown Community Games Carlow Bagenalstown Cricket Club Carlow Bagenalstown Family Resource Centre Ltd Carlow Bagenalstown Karate Club Carlow Bagenalstown Pitch & Putt Club Carlow Bagenalstown Swimming Club Carlow Ballinabranna GAA Club Carlow Ballinkillen Hurling Club Carlow Ballinkillen Lorum Community Centre Club Carlow Ballon GAA Club Carlow Ballon Hall Committee Limited Carlow Ballon Karate Club Carlow Ballymurphy Celtic AFC Carlow Ballymurphy Hall Ltd Carlow Ballymurphy Indoor Soccer Club Carlow Barrow Valley Riding Club Carlow Bennekerry N.S Carlow Bigstone Community Centre Carlow Borris Golf Club Carlow Borris Tidy Towns Association Ltd Carlow Borris/St. Mullins Community Games Carlow Burrin Celtic F.C. Carlow Carlow & District Juveniles League Carlow Carlow Basketball Club Carlow Carlow Carsports Club CLG Carlow CARLOW COUNTY COUNCIL Carlow Carlow Cricket Club Carlow Carlow Dragon Boat Club Carlow Carlow Golf Club Carlow Carlow Gymnastics Club Carlow Carlow Hockey Club Carlow Carlow Karate Club Carlow Carlow Kickboxing Club Carlow Carlow Lawn Tennis Club Carlow Carlow Road Cycling Club Carlow Carlow Rowing Club Carlow Carlow Scot's Church Carlow Carlow Special Olympics Club Carlow Carlow