Youtube Yinzers: Stancetaking and the Performance of 'Pittsburghese' Scott F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pittsburgh I Remember Is a City That Will Use This Act of Hate to Build a Place of Love and Hope

THE PITTSBURGH I REMEMBER IS A CITY THAT WILL USE THIS ACT OF HATE TO BUILD A PLACE OF LOVE AND HOPE By Ron Sirak • @ronsirak October 28, 2018 I remember the old Pittsburgh, the grimy city of steel mills and pollution, a lunch pail-carrying kind of place where the sweat of the blast furnaces was washed away with a shot and a beer. I remember a fiercely proud area that viewed Eastern Pennsylvania as another state, perhaps even another country. Pittsburgh, Western Pennsylvania, even has its own language. Phrases such as: “What yinz doin’ after you red up the house?” clang on the outsider’s ear like the wail of a car alarm at 3 in the morning. My mother, who worked as a welder from 7 a.m. until 3:30 p.m. and then as a cleaning woman in an office from 6 p.m. to 9 p.m., said of Eastern Pa.: “They’re from the anthracite region; we’re from the bituminous region,” as if that was a stamp you’d get on your passport. My father drove a ladle crane in about every mill in Western Pa. and Eastern Ohio as the steel industry was dying. United Engineering. Mesta Machine. Youngstown Sheet & Tube, Sharon Steel, Jones & Laughlin and finally Pennsylvania Engineering in our hometown of New Castle, 50 miles from Pittsburgh. That’s where he was working when he died at the age of 45, the life sucked from him by relentlessly hard work. When I was a kid the Interstate hadn’t been built yet and the drive to Pittsburgh to see a Pirates game at Forbes Field was an arduous affair, following a windy road that that traced the river. -

Undergraduate Spotlight: Getting to Know You

Children’s School October 2012 Undergraduate Spotlight: Getting to Know You As a campus laboratory school, the Children’s School offers research and observation opportunities to many undergraduate and graduate students from different departments across campus. In addition to these opportunities, we offer undergraduates a chance to work in the classrooms on a regular basis, either as student employees, interns, or volunteers. In the Undergraduate Spotlight, we will be featuring each of our undergraduate assistants so that parents can learn about the students who work in the classrooms with their children. Photos are posted on the Family Communication bulletin board. Child Development Interns • Alicia Low (AM 3’s) is a senior studying linguistics and psychology. She enjoys writing, reading, baking, painting, doing crafts, and traveling. • Matt Mastricova (AM 4’s) is a DJ at the CMU campus radio station and writes for the New Yinzer, a Pittsburgh literary magazine. He is a junior psychology and creative writing major. • Sara Mouhktar (PM 3’s) works as an RA and in the infant language learning lab. She is a senior majoring in psychology and English. • Marisa Wiltsie (Kindergarten) enjoys sewing and cospla (costume play). She is a junior majoring in psychology and plans to become a counselor for children. Student Employee of the Month Caroline Landau is a senior art major from Reading, PA. She loves teaching and spending time with the children, especially in artistic activities that reveal their amazing imagination. She says working at the Children’s School is one of her favorite parts of college because of the incredible learning environment, the teachers, and - of course - the children! No two days are alike, and for that reason it is always exciting. -

MICHAEL S. BEGNAL [email protected]

MICHAEL S. BEGNAL [email protected] EDUCATION M.F.A., North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC English, Creative Writing – Poetry. Thesis: “Red Horse.” John Balaban, Director. B.A., Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA English Literature. TEACHING POSITIONS HELD Assistant Teaching Professor (Full-Time), Department of English, Ball State University, Muncie, IN August 2015-Present. Creative writing and first-year writing. Instructor (Full-Time), Department of English, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA August 2013-May 2015. Creative writing, literature, and first-year writing. Instructor (Part-Time), Department of English, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA August 2009-May 2013. Creative writing and first-year writing. Instructor (Part-Time), Department of English, Wake Technical Community College, Raleigh, NC August 2008-May 2009. First-year writing. Graduate Teaching Assistant, Department of English, NC State University, Raleigh, NC August 2006-May 2008. Creative writing. PUBLICATIONS Poetry Collections Future Blues. Cliffs of Moher, Ireland: Salmon Poetry, 2012. 86 pages. Print. Ancestor Worship. Cliffs of Moher, Ireland: Salmon Poetry, 2007. 70 pages. Print. Chapbooks The Muddy Banks. Syracuse, NY: Ghost City Press, 2016. 30 pages. Print. Mercury, the Dime. Pittsburgh: Six Gallery Press, 2005. 46 pages. Print. As Editor Honeysuckle, Honeyjuice: A Tribute to James Liddy. Ed. Michael S. Begnal. Galway, Ireland: Arlen House, 2006. 144 pages. Print. The Burning Bush literary magazine. Spring 1999 to Spring 2004. Eleven issues published. Print. Refereed Articles “‘Bullets for Hands’: Witter Bynner, Arthur Davison Ficke, and the Spectra Poems of World War I.” Twentieth- Century Literature. Accepted. Expected publication in 2018. “Modernist Mythologies: The Turquoise Trail Anthology and the Poets of Santa Fe.” Western American Literature. -

“Battle of the Pronouns” 72 Texas Linguistics Forum 55:72-79 Pr

72 What’s up with y’all?: Sociopragmatic versatility in the “battle of the pronouns” Shawn Warner-Garcia University of California, Santa Barbara 1. Introduction There has been much debate – mostly of a historical or grammatical nature - over the development and use of the second-person plural (2PPL) pronominal form y’all in American English. Accurate historical documentation of the form is scant, resulting in a wide range of theories regarding its origin, with some authors proposing that y’all is a calque of a creole or African pronoun system (Lipski, 1993) and others arguing that it is an importation from the Scots-Irish dialect (Montgomery 1992). Grammatically, it is generally accepted that y’all is an analogous suppletion of the Early Modern English pronoun system (Maynor, 2000; Tillery, Wilke, and Bailey, 2000), though it is certainly not the only form that fills the 2PPL pronoun slot in modern-day American English. While you is the accepted singular second-person form, it also and often functions as an implicit plural. Other pronouns in American English comparable to y’all include yinz (Johnstone, 2001), you-uns (Montgomery, 2002; Donahue 2007), and you guys (Maynor, 2000). These forms, along with y’all, have been shown to index certain aspects of identity such as social class, region, or ethnicity. However, the discourse-pragmatic functions of these forms have not been investigated. In this paper, I show how y’all in particular serves distinct sociopragmatic purposes by indexing affective stances among young Texas speakers. I analyze a corpus of interactional video data in order to determine the state of y’all in what has been called the “battle of the pronouns” (Maynor, 2000). -

Potentiation of Neuromuscular Transmission As a Therapeutic Strategy to Improve Motor Function in Spinal Muscular Atrophy By

Title page Potentiation of neuromuscular transmission as a therapeutic strategy to improve motor function in spinal muscular atrophy by Kristine Susan Ojala B.A. Psychology, California State University, Long Beach, 2011 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2020 Committee page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Kristine Susan Ojala It was defended on July 28, 2020 and approved by Anne-Marie Oswald, Associate Professor, University of Pittsburgh Jon W. Johnson, Professor, Department of Neuroscience, University of Pittsburgh Zachary P. Wills, Assistant Professor, Department of Neurobiology, University of Pittsburgh Christopher Donnelly, Assistant Professor, Department of Neuroscience, University of Pittsburgh Christine J. DiDonato, Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Northwestern University Dissertation Director: Stephen D. Meriney, Professor, Department of Neuroscience, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by Kristine Susan Ojala 2020 iii Abstract Potentiation of neuromuscular transmission as a therapeutic strategy to improve motor function in spinal muscular atrophy Kristine Ojala, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2020 Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) is a genetic disease caused by a null mutation of the SMN1 gene. Loss of SMN1 results in low levels of a protein called Survival of Motor Neuron (SMN), which is a protein that is critical for neuromuscular development. The first FDA-approved treatment for SMA utilizes intrathecal injections of an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) to increase expression of SMN. Despite the immense excitement for this treatment, however, preliminary clinical observations and studies in SMA mouse models indicate persistent neuromuscular weakness, which reveals the need for an additional symptomatic treatment that targets neuromuscular function. -

'Hoods: Place Branding and the Reconstruction of Identity in Rick Sebak's Pittsburgh Documentaries

HOUSES, HOT DOGS, AND 'HOODS: PLACE BRANDING AND THE RECONSTRUCTION OF IDENTITY IN RICK SEBAK'S PITTSBURGH DOCUMENTARIES Bryan James McGeary A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2012 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Ellen W. Gorsevski Graduate Faculty Representative Cynthia Baron Scott Magelssen © 2012 Bryan James McGeary All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor This project investigates the implementation of place branding theory via documentary filmmaking focused closely on the local characteristics of a place/region. Employing a close reading of WQED filmmaker Rick Sebak’s Pittsburgh History Series focused upon recurrent themes about aspects of Pittsburgh’s unique identity framed in relation to rhetorical approach and documentary techniques, while also noting aspects left out of Sebak’s films, this dissertation demonstrates the progressive potential of publicly funded documentary filmmaking to enable the residents of a given place to rebrand their identity and foster revitalization, independent of the expectations of city planners or corporate sponsors, and without sacrificing the diversity of experiences that give that place its unique character. As a whole, Sebak’s body of work constructs a particular narrative of Western Pennsylvania’s identity that revamps some of the preexisting notions about that identity. As a project of self-definition and self-understanding, the Pittsburgh History Series provides the local populace with some agency in recreating its image, rather than being branded from the outside. The success of this place branding approach to documentary filmmaking for Sebak and Western Pennsylvania suggests that other cities and regions could use it as a model to take greater control of their identities and cultivate renewal. -

We're from the Town with the Great Football Team

WE‟RE FROM THE TOWN WITH THE GREAT FOOTBALL TEAM: A PITTSBURGH STEELERS MANIFESTO By David Villiotti June 2009 1 To… Idie, Anthony & “Mrs. Swiss” ...tolerating my mania Tony …infecting me with Steelers Fever Mom …see Line 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Preface 4 January, 2008 7 Behind Enemy Lines 8 Family of Origin…Swissvale 13 The Early Years: Pitt Stadium Days 18 Forbes Field Memories 28 Other Burgh Sports 34 Tony 38 Rest of The Boys 43 1970s: Unparallelled 46 Why Roy Gerela 64 1980s: Dark Decade 68 Why Mrs. Swiss Hates the Steelers 79 Stuff I Hate about the NFL 83 „90s: Changing of the Guard 87 Heckling 105 Family Gatherings 108 Taping 111 Rooting for Injuries 115 13 Minutes Ain‟t Enuff 120 Y2K Decade: First Five Years…Still Waiting 124 One For The Thumb 133 Cowher Out…Tomlin In 140 Steelers Trivia Challenge 145 Steelers Sites: Mill, Fury, Spiker, et al 149 Six!!! 156 City of Champions 209 Closing 214 *From “The Steelers Polka” by Jimmy Psihoulis 3 PREFACE Having catalogued my life by the ups and downs of the Pittsburgh Steelers Football Club, and having surpassed the half century mark in age, I endeavored to author a memoir of my life as a fan. This perhaps would be suited for a time capsule for my children, or alternatively as a project for a publisher whose business was really, really slow. For the past few years, I‟ve written a number of articles, under the screen name, Swissvale72 for a few Pittsburgh Steelers related websites, most notably, and of longest duration, was an association with Stillers.com, prior to my falling into disfavor with management. -

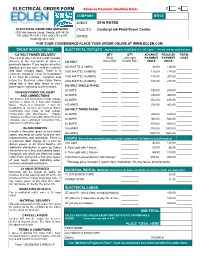

ELECTRICAL ORDER FORM Advance Payment Deadline Date: E M COMPANY: BTH

ELECTRICAL ORDER FORM Advance Payment Deadline Date: E M COMPANY: BTH # EVENT: 2016 RATES ELECTRICAL EXHIBITION SERVICES FACILITY: CenturyLink Field Event Center 5931 4th Avenue South, Seattle, WA 98108 Ph: (206) 781-2411 Fax: (206) 781-2270 DATES: [email protected] FOR YOUR CONVENIENCE PLACE YOUR ORDER ONLINE AT WWW.EDLEN.COM ORDER INSTRUCTIONS ELECTRICAL OUTLETS Approximately 120V/208V A.C. 60 Cycle - Prices are for entire event 120 VOLT POWER DELIVERY QTY QTY ADVANCE REGULAR TOTAL The cost of one 120-Volt outlet includes Show 24hrs/day PAYMENT PAYMENT COST delivery to the rear-center of inline or 120 VOLT Hours Only Double Rate PRICE PRICE peninsula booths. If you require an outlet distributed to any other location, material 500 WATTS (5 AMPS) 84.00 126.00 and labor charges apply. There is a 1000 WATTS (10 AMPS) 116.00 174.00 minimum charge of 1 hour for installation & 1/2 hour for removal. Complete and 1500 WATTS (15 AMPS) 138.00 207.00 return the Electrical Labor Order Form 2000 WATTS (20 AMPS) 158.00 237.00 along with a floor plan layout of your booth space indicating outlet locations. 208 VOLT SINGLE PHASE 20 AMPS 190.00 285.00 208/480V POWER DELIVERY 30 AMPS 240.00 360.00 AND CONNECTIONS The delivery and connection of high voltage 60 AMPS 402.00 630.00 services is done on a time and material basis. There is a minimum 1 hour for 100 AMPS 534.00 802.00 installation & 1/2 hour for removal. Edlen 208 VOLT THREE PHASE electricians must make all high voltage connections and disconnects. -

Name Pittsburgh Resident Action Comment Patrick Beckhorn

Name Pittsburgh Action Comment Resident Patrick Beckhorn Yes Remove Columbus was a delusional racist slave owner who caused genocide, so why exalt him by erecting and protecting a large public monument to him? One would only do that if they were ignorant of history. Well, they might do it if they were ignorant of history, but they would also do it if they were a racist piece of shit... Rohit Kartan Yes Remove Emilia Farmerie-Rishel No Remove Ty Hinkle Yes Remove Karsen Shoger Yes Remove The Columbus statue glorifies the history of colonialism, which caused extreme amounts of harm to native peoples in America as well as the environment in America. It is time to let go of these relics that glorify a destructive history, filled with violence and death, as many other cities across America are doing. Keeping the Columbus statue broadcasts a clear message exalting the history of lack of care for humanity of colonists and imperialists. If we want to stand by the ideals of equity and social justice, removing this symbol of inequity and harm from our city. Daniel Galvin Yes Remove The Christopher Columbus statue in Shenley Park should be immediately removed with all expediency - which is why the process of replacement or alternation, and accompanying delays, is unacceptable as well. The fact that it has remained there this long is an embarrassment to Pittsburgh, and an insult to the native people whose land this was for thousands of years. For native people - including friends of mine whose viewpoints I greatly value - this is tantamount to a statue of Hitler in a Jewish neighborhood, or a monument commemorating the cross-Atlantic slave trade being erected in a black neighborhood. -

GIS Applications in Studying Dialect of Western Pennsylvania Ayad Y

Mapping Dialect: GIS Applications in Studying Dialect of Western Pennsylvania Ayad Y. and Luthin H Mapping Dialect: GIS Applications in Studying Dialect of Western Pennsylvania Ayad, Y. ([email protected]) Luthin, H. ([email protected]) Clarion University of Pennsylvania Abstract Historically, most surveys of American dialect have focused on large‐scale regions of the country: the Linguistic Atlas of New England, the Linguistic Atlas of the Middle and South Atlantic States, and the Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States, for example. However, even in a region as small and relatively homogeneous as western Pennsylvania, there is measurable diversity of language. This paper describes a dialect survey, in progress for the last 10 years that focuses precisely on dialect variation within western Pennsylvania. In recent years, the researchers have tapped the potential of GIS techniques to help make these distributions visible and assess the underlying speech patterns of the region. This paper is an attempt in this direction. It demonstrates the methods and techniques used to manipulate the collected data and the process of creating visual cartographic representations of the results. Introduction The essence of dialectology is the study of variation in language. Variation can be found at every level of language, from the nuances of pronunciation and the details of verb conjugations, to the structure of sentences, the content of the vocabulary, and patterns of interaction between individuals. The field of dialectology today is pursued down all of these avenues and more, and from a multitude of perspectives (social, anthropological, diachronic, synchronic, longitudinal, qualitative, quantitative, statistical), but it had its origins in the study of regional variation—the geography of language—and cartography was at the heart of its enterprise. -

Yinzcam: Experiences with In-Venue Mobile Video and Replays Nathan D

YinzCam: Experiences with In-Venue Mobile Video and Replays Nathan D. Mickulicz, Priya Narasimhan, and Rajeev Gandhi, YinzCam, Inc. and Carnegie Mellon University https://www.usenix.org/conference/lisa13/technical-sessions/papers/mickulicz This paper is included in the Proceedings of the 27th Large Installation System Administration Conference (LISA ’13). November 3–8, 2013 • Washington, D.C., USA ISBN 978-1-931971-05-8 Open access to the Proceedings of the 27th Large Installation System Administration Conference (LISA ’13) is sponsored by USENIX. YinzCam: Experiences with In-Venue Mobile Video and Replays Nathan D. Mickulicz, Priya Narasimhan, Rajeev Gandhi YinzCam, Inc. / Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract YinzCam allows sport fans inside NFL/NHL/NBA venues to enjoy replays and live-camera angles from different per- spectives, on their smartphones. We describe the evolu- tion of the system infrastructure, starting from the initial in- stallation in 2010 at one venue, to its use across a dozen venues today. We address the challenges of scaling the system through a combination of techniques, including dis- tributed monitoring, remote administration, and automated replay-generation. In particular, we take an in-depth look at our unique automated replay-generation, including the dash- board, the remote management, the remote administration, and the resulting efficiency, using data from a 2013 NBA Playoffs game. Figure 1: Fan experience at the original Mellon Arena deployment for YinzCam, May 2010, showing three dif- ferent smartphones displaying three different live cam- 1 Introduction era angles for a Pittsburgh Penguins home game. -

Forms and Functions of Second Person Plural Forms in World Englishes: a Corpus-Based Study

Forms and Functions of Second Person Plural Forms in World Englishes: a corpus-based Study Liviana Galiano This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2020 Department of Linguistics and English Language 1 Declaration This thesis has not been submitted in support of an application for another degree at this or any other university. It is the result of my own work and includes nothing that is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated. Many of the ideas in this thesis were the product of discussion with my supervisor Willem Hollmann. Liviana Galiano Lancaster University, UK 2 Abstract The present work is a corpus-based research on the plural forms of the second person pronoun you (2PL forms henceforth) which focuses on the similarities and differences among twenty varieties of English. The corpus (GloWbe) contains 1.9 billion words collected on the web in 2012. The 2PL forms I have analysed are the result of both morphological and analytic strategies of number marking: yous(e), yi(s/z), yus, you guys, you all and y(')all, you two, you three, you four, you ones and y(ou)'uns/yin(s/z), you lot and other you + NP-PL expressions. The aim of my research is provide an empirically informed description of the forms and functions of 2PL forms in contemporary English. This is done by combining the analysis of corpus data with the literature on 2PL forms as well as the relevant theories on language change. The results show that there are two main geographically-related trends in the use of 2PL forms: analytic strategies are preferred in the US, whereas morphological strategies are preferred in the European and Australian varieties of English.