Why Black? a Dutch Desire for the Colour Black Between 1675-1725

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scenic Wallpaper – First Quarter 19Th Century Western European Interior Décor in Latvia

Proceedings of the Latvia University of Agriculture Landscape Architecture and Art, Volume 1, Number 1 Scenic Wallpaper – First Quarter 19th Century Western European interior décor in Latvia Laura Lūse, Latvian Academy of Art Abstract. In the early 19th century French scenic wallpaper rapidly gained popularity as the preferred type of interior décor in the homes of country noblemen and rich merchants. The main characteristic of this type of wallpaper is the continuous and unbroken depiction of panoramic scenes that feature exotic countries, prevalent outdoor hobbies and scenes from the natural world, transforming each room into an almost illusory space. Thus the nature was carried indoors in a rather poetic way. It has been established that scenic wallpaper was used in a number of interiors found in the territory of present-day Latvia. This article will present a detailed analysis of these interiors. Keywords: scenic wallpaper, interior, wallpaper trade. Introduction Many experts within the wallpaper scenic wallpaper? How widely available was this manufacturing industry regard scenic wallpaper as interior décor in the present-day Latvian territory one of its highest achievements, not just because of and what trade routes were utilised in its the complex technologies required to produce it but acquisition? The answers to these questions will also of its artistic value. Scenic wallpaper differs provide new insights and contribute towards the from the other types of 19th century wallpaper in a research of 19th century Latvian interiors. considerable way - just like a painting this wallpaper depicts unbroken and continuous scenery without Methodology repeating some or all of its elements. -

Association of the Overseas Countries and Territories

COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES COMPILATION OF TEXTS ASSOCIATION OF THE OVERSEAS COUNTRIES AND TERRITORIES FRENCH OVERSEAS DEPARTMENTS 1 January 1986 - 31 December 1986 COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES COMPILATION OF TEXTS X ASSOCIATION OF THE OVERSEAS COUNTRIES AND TERRITORIES FRENCH OVERSEAS DEPARTMENTS 1 January 1986 - 31 December 1986 This publication is also available in: ES ISBN 92-824-0485-4 DA ISBN 92-824-0486-2 DE ISBN 92-824-0487-0 GR ISBN 92-824-0488-9 FR ISBN 92-824-0490-0 IT ISBN 92-824-0491-9 NL ISBN 92-824-0492-7 PT ISBN 92-824-0493-5 Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1988 ISBN 92-824-0489-7 Catalogue number: BY-50-87-235-EN-C © ECSC-EEC-EAEC, Brussels · Luxembourg, 1988 Reproduction is authorized, except for commercial purposes, provided the source is acknowledged Printed in Luxembourg 3 - CONTENTS Part 1 : OCT I - TRANSITIONAL MEASURES Page Council Decision 86/46/EEC of 3 March 1986, extending Decision 80/1186/EEC on the association of the OCT with the EEC 13 Council Decision 86/48/ECSC of 3 March 1986 extending Decision 80/1187/ECSC opening tariff preferences for products within the province of the ECSC Treaty and originating in the OCT associated with the Community 14 II - BASIC TEXTS Page Council Decision 86/283/EEC of 30 June 1986 on the association of the OCT with the EEC (1) 17 Council Decision 86/284/EEC of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States, meeting within the Council, of 30 June -

GENERAL AGREEMENT on 16 November 1973 TARIFFS and TRADE Limited Distribution

RESTRICTED L/3954 GENERAL AGREEMENT ON 16 November 1973 TARIFFS AND TRADE Limited Distribution GENERALIZED SYSTEM OF PREFERENCES Notification by the European Communities With reference to the Decision of the CONTRACTING PARTIES of 25 June 1971 concerning the Generalized System of Preferences and the previous notifications by the European Communities on the implementation of the generalized tariff preferences accorded by the European Economic Community (documents L/3550 and L/3671), the Commission of the European Communities has transmitted for the information of the contracting parties the text of the regulations and decisions adopted by the Council of the European Communities in respect of the application of the scheme for the year 1973.1 The regulations and decisions are the following: - Regulations (EEC) No. 2761/72 to No. 2767/72 - Decisions No. 71/403 and 71/404/ECSC 1The EEC's GSP scheme for 1973 reproduced in the present document is applied by the six original member States. This scheme is scheduled to be replaced in 1974 by a scheme to be pplied by the enlarged Community of nine members. L/3954 (ii) CONTENTS Council Regulation (EEC) No. 2761/72 of 19 December 1972 concerning the establishment, sharing and management of Community tariff quotas for certain products originating in developing countries ....................1 Council Regulation (EEC) No. 2762/72 of 19 December 1972 concerning the establishment of tariff preferences for certain products originating in developing countries ......................... 15 ... Council Regulation (EEC) No. 2763/72 of 19 December 1972 concerning the establishment, sharing and management of Community tariff quotas for certain textile products originating in developing countries ................. -

FACT SHEET INDONESIA-KOREA LEATHER 5Th Edition 2016

FACT SHEET INDONESIA-KOREA LEATHER 5Th Edition 2016 Leather is a durable and flexible material created by tanning animal rawhide and skin, often cattle hide. It can be produced at manufacturing scales ranging from cottage industry to heavy industry. People use leather to make various goods—including clothing (e.g., shoes, hats, jackets, skirts, trousers, and belts), bookbinding, leather wallpaper, and as a furniture covering. It is produced in a wide variety of types and styles, decorated by a wide range of techniques. Most of the leather product exported by Indonesia Leather is one of the most widely traded commodities are sport gloves, leather jacket, casual shoes, woman in the world. The leather and leather products handbag and other accessories, of leather or industry plays a prominent role in the world’s composition leather. Leather product in South Korea economy. The total export of world gained in 2015 mostly come from China. Based on the rising demand amounted US$ 75.2 billion. China is the top notch for Leather product in Rep of Korea, that making Rep country which contributed total export 42% of the of Korea became one of target import Leather total world export. Indonesia have a slight role which product market especially in fashion,and Indonesia exported also to the world valued US$ 323 million will try to increase export Leather product to Rep of and ranked 22th place. This amount is still potent to Korea . expanding year by year. Rep of Korea is one of the countries which imported World’s export HS Code 42 also much of leather product. -

ISSN: 2320-5407 Int. J. Adv. Res. 5(9), 1713-1717

ISSN: 2320-5407 Int. J. Adv. Res. 5(9), 1713-1717 Journal Homepage: -www.journalijar.com Article DOI:10.21474/IJAR01/5498 DOI URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/5498 RESEARCH ARTICLE FUTURE PROSPECTS OF INDIAN LEATHER INDUSTRY. Dr. K. Thiripurasundari and C. Ponsakthisurya Sri Parasakthi College for Women,Courtallam-627802. …………………………………………………………………………………………………….... Manuscript Info Abstract ……………………. ……………………………………………………………… Manuscript History Leather industries have a prominent place in India. It gives a more employment opportunity. Especially women employees are high. It Received: 22 July 2017 plays a unique position in Indian Economy but the industries run profit Final Accepted: 24 August 2017 motive and earn more profit through the leather product clusters like Published: September 2017 leather finished goods, leather garments leather footwear, saddler and Keywords:- harness. Tamilnadu has more leather cluster region like Leather Industry, Export, Leather AmburVaniyambadi, Pernambut, Ranipet, Dindugul, Trichy. Theses Garments, Footwear, saddler and cluster exports more leather products among other states of India. So harness. India earn more annual turnover through leather industry because it has more region all over India and export more Leather products to all country. Hence, an attempt has been made in this paper to highlight “Future Prospects of Indian Leather Industry”. Copy Right, IJAR, 2017,. All rights reserved. …………………………………………………………………………………………………….... Introduction:- The Indian Leather Industry occupies a unique position in the Indian economy. Leather is a durable and flexible material created by the tanning of animal rawhide and skin, often cattle hide. It can be produced through manufacturing processes ranging from cottage industry to heavy industry. Leather is used for various purposes including clothing, bookbinding, leather wallpaper, and as a furniture covering. -

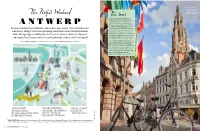

Antwerp’S Cathedral of Our Lady Rises 123 Metres High – Making It the Tallest in the Low Countries

The tower of Antwerp’s Cathedral of Our Lady rises 123 metres high – making it the tallest in the Low Countries On Antwerp’s peaceful left bank, Jona de The Perfect Weekend BeuckeleerThe points out the landmarkstour of the city’s skyline across the river: the slender cathedral, the Art Deco glamour of Europe’s ANTWERP first skyscraper, the Gothic church of St Paul’s. He’s leading the Marnix bike tour, one of four Antwerp is Belgium’s second city, and its best-kept secret. Once a Renaissance offered by Cyclant, the company he runs with his friend and fellow Antwerp native Nicolas. metropolis, today this fashion and design centre combines historic character Teachers by trade, they give an entertaining inside track on storied spots and less-pedalled with cutting-edge creativity. Head out on two wheels, delve into the past places alike. On Marnix, for example, they take participants through the old town, with its and sample local flavours on a weekend exploring Flanders’ unofficial capital medieval houses and riverside castle, and also the left bank and docklands. At Park Spoor l WORDS SOPHIE MCGRATH @sophielmcgrath PHOTOGRAPHS JONATHAN STOKES @StokesJon Noord, reclaimed rail tracks lead beside grassy lawns and street art, while in multicultural Borgerhout, the colourful arches of Chinatown frame the grand domes of Antwerpen-Centraal station. Antwerp is a walkable city, but to see some of its most interesting corners it’s best to make like the Belgians and saddle up. l Marnix tour from £13; cyclant.com TRAVEL ESSENTIALS Eurostar services from London start at £83 return (incl local rail transfer from Brussels). -

The Culture of Materials and Leather Objects in Eighteenth-Century England

The Culture of Materials and Leather Objects in Eighteenth-Century England Thomas Benjamin Sykes Rusbridge Department of History A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for School of History and Cultures the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY March 2019 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This study of leather examines material culture in England, c.1670-1800. Following raw hide to leather, leather to object, and object to possessed commodity, this thesis traces the production, retail, and consumption of three representative leather objects: saddles, chairs and drinking vessels. The analysis of these three objects is principally informed by materials, and draws on inventories, advertisements, literary and technical texts, visual sources and ephemera, and other object types with which they shared consumption contexts, practices of making or decoration. This thesis argues, first, that the meanings consumers derived from materials, which informed their responses to objects, were created across the full life-cycle of a material: from production to consumption. Second, while leather exhibited principal properties which made it useful across several objects, its meanings and associations played out differently and unevenly across different object types. -

GENERAL AGREEMENT on COM TD/W/LLDC/3 TARIFFS and TRADE Limited Distribution

RESTRICTED GENERAL AGREEMENT ON COM TD/W/LLDC/3 TARIFFS AND TRADE Limited Distribution Sub-Committee on Trade of Least-Developed Countries 13 July 1981 EXPORT INTERESTS OF LEAST-DEVELOPED COUNTRIES (Tariffs, Non-Tariff Measures and Trade Flows) Prepared by the Secretariat 1. As indicated in the Annex to the note on proceedings of the first meeting of the Sub-Committee (COMTD/LLDC/1), point (iii) of the Sub-Committee's future work is concerned with the identification of the export interests of least-developed countries and the commercial policy measures applied to the products of such countries in major markets. In this respect, the Sub-Committee noted that consideration of this matter could be based on a secretariat background note providing statistical as well as tariff and trade information on selected items exported by individual least-developed countries and showing developed country markets and the commerciaL policy applied. 2. The Annex indicates further that least-developed countries could be invited to notify additional products of export interest. In addition, particular points relating to the application of the non-tariff measures agreements could be raised. 3. The Annex also states that the object wouLd be to identify continuing barriers to the exports of least-developed countries for discussion, comment and suggestions in the Sub-Committee, as a contribution to work on the possibilities for further trade liberalization in the Sub-Committee itself or in other contexts. A summary of the views and comments put forward on this matter at the Sub-Committee's first meeting may be found in paragraphs 6-11 of COM.TD/LLDC/1. -

UC Santa Barbara Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Public Displays of Affection: Negotiating Power and Identity in Ceremonial Receptions in Amsterdam, 1580–1660 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art and Architecture by Suzanne Decemvirale (née Suzanne van de Meerendonk) Committee in charge: Professor Ann Jensen Adams, Chair Professor Mark A. Meadow Professor Richard Wittman December 2018 The dissertation of Suzanne Decemvirale is approved. ____________________________________________ Richard Wittman ____________________________________________ Mark A. Meadow ____________________________________________ Ann Jensen Adams, Committee Chair December 2018 Public Displays of Affection: Negotiating Power and Identity in Ceremonial Receptions in Amsterdam, 1580–1660 Copyright © 2018 by Suzanne van de Meerendonk iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The idea for this dissertation was first conceived during my time as an MA student at the University of Amsterdam in 2010. For key considerations in this project that are still evident in its final version, I am indebted to Eric Jan Sluijter and Jeroen Jansen. Since its conception this project has additionally benefited from the wisdom and mentorship of professors, colleagues, family and friends, as well as financial support provided by several institutions. For each of these contributions I am immensely grateful, as they allowed such incipient ideas to materialize in the manuscript before you today. My largest debt and greatest thanks is to my adviser Ann Jensen Adams, who was my first advocate at UCSB and a constant source of expertise and encouragement during the almost seven years that followed. I am also thankful to Mark Meadow and Richard Wittman for their thoughtful insights as members of my doctoral committee. -

IEEE/PCS Professional Communication Society Newsletter

IEEE/PCS Professional Communication Society Newsletter IEEE Professional Communication Society Newsletter • ISSN 1539-3593 • Volume 50, Number 11 • November 2006 Quick-Starting User-Centered Design by Anita Salem Many of the people I work with who are trying to design information and interfaces understand the benefits of focusing on the users, but often don’t know where to start. They are writers, UI designers, programmers, and program managers. They operate at the “doing” level of organizations, and are constantly looking at improving their processes under tight budgets and short time-lines. Usually, they’ve read a bit about usability or task analysis, but they don’t have a great deal of experience or knowledge in pulling it all together. Read more... ● Tools Managing the “Technical” in Technical Communication The appearance of word processors in the late 1970s changed how we write our material and began the growth of the “technical” aspect of technical writing. Today, the technical aspect seems overwhelming; technical communicators can say with a straight face ...Read more. ● Election Results Congratulations to the Winners of the PCS AdCom Elections! The AdCom is now composed of representatives from Regions 1-6 (USA), Region 7 (Canada), Region 8 (Europe/Middle East/Africa), Region 9 (Latin/South America), and Region 10 (Asia Pacific). Please join us in welcoming the following people to the IEEE-PCS AdCom...Read more ● ABET What to Expect from an ABET Site Visit An ABET site visit might not seem like a sufficiently substantial topic for this column. And yet, as someone who had always been on the periphery of previous ABET visits, I was curious to witness firsthand what would go on when the group of evaluators and observers arrived on our campus. -

The History of Schloss Vollrads. Welcome to the Chronicle of Schloss Vollrads

SCHLOSS VOLLRADS VINOTHEK GMBH & CO. BESITZ KG Tel. +49 6723 66 26 Schloss Vollrads 1 65375 Oestrich-Winkel GUTSRESTAURANT Tel. +49 6723 66 0 Tel. +49 6723 66 0 Fax. +49 6723 66 66 E-Mail: [email protected] www.schlossvollrads.com THE HISTORY OF SCHLOSS VOLLRADS. WELCOME TO THE CHRONICLE OF SCHLOSS VOLLRADS. 6 1 7 4 2 5 3 3 1 Schloss Vollrads Trademark with Crest 2 Manor House 3 Vineyard 4 Coach House & Vinothek 5 Residential Tower 6 Cabinet Cellar 7 Restaurant 1097 Family Tree The name Greiffenclau is first mentioned in an official document in the year 1097. As lords of Winkel, the Greiffenclaus were the dominant family in the Rheingau region. The name Greiffenclau is derived from the crest: The Greiffenclaus themselves, their vassals as well as the soldiers and the knights fighting for them were recog- nizable by the claw of the griffin, which they wore on their helmets and shields. This family tree shows 18 generations of Greiffenclaus from 1280 to 1902. Schloss Vollrads was owned by the family up until the 27th generation. Thus it probably is the oldest family business in the world. 1211 Worldwide’s oldest wine bill In the summer of the year 1211, a certain true in the case of the Steinberg, their own Frederick is elected King of the Romans in local vineyard. Nuremberg. Bearing the name Frederick II, he is going to make medieval history as the We have no record of how the Greiffenclaus, last emperor of the House of Hohenstaufen. lords over the little village of Winkel, regarded Down in Rome, Pope Innocent III will have their grey-robed neighbors. -

OFFENBACH 2012 POSTPRINTS of the 10Th Interim Meeting

OFFENBACH ICOM OFFENBACH - CC LEATHER & RELATED August 29 2012 - 31, 2012 ICOM-CC LEATHER & RELATED MATERIALS WORKING GROUP POSTPRINTS MATERIALS WORKING GR of the 10th Interim Meeting OUP EDITED BY CÉLINE BONNOT-DICONNE, CAROLE DIGNARD AND JUTTA GÖPFRICH ICOM-CC Leather and Related Materials WG Offenbach 2012 2 ICOM-CC Leather and Related Materials WG Offenbach 2012 POSTPRINTS of the 10th Interim Meeting of the ICOM-CC Leather & Related Materials Working Group Offenbach, Germany 2012 ACTES de la 10ème Réunion Intermédiaire du Groupe de Travail Cuir et Matériaux Associés de l’ICOM-CC Offenbach, Allemagne 2012 Edited by/ Sous la direction de Céline Bonnot-Diconne (2CRC), Carole Dignard (Canadian Conservation Institute / Institut Canadien de Conservation), Jutta Göpfrich (Deutsches Ledermuseum Schuhmuseum). 3 ICOM-CC Leather and Related Materials WG Offenbach 2012 4 ICOM-CC Leather and Related Materials WG Offenbach 2012 Organizing committee / Comité d’organisation Villa Médicis, Rome, Italy and 2CRC, Moirans, Céline Bonnot-Diconne France Carole Dignard ICC/CCI, Ottawa, Canada Nina Frankenhauser Offenbach, Germany Jutta Göpfrich Offenbach, Germany Editorial Committee / Comité de lecture Céline Bonnot-Diconne 2CRC, Moirans, France Carole Dignard ICC/CCI, Ottawa, Canada Theo Sturge Northampton, United-Kingdom Acknowledgments / Remerciements - ICOM Germany, Dr. Klaus Weschenfelder (President) - DLM- Deutsches Ledermuseum/ Schuhmuseum Offenbach - Académie de France à Rome, Villa Médicis (Eric de Chassey, Annick Lemoine). - Canadian Conservation Institute/Institut canadien de conservation These Postprints have been supported by Hermès. Cette publication a bénéficié du soutien de la Maison Hermès. © ICOM-CC March 2013 ISBN 978-3-9815440-1-5 To order this book, please contact: DLM- Deutsches Ledermuseum/ Schuhmuseum Offenbach Frankfurter Strasse 86 D-63067 Offenbach, Germany T.