Personnel and Programs of Economic Reform Begin to Emerge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Data Supplement

China Data Supplement October 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 29 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 36 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 45 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR................................................................................................................ 54 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR....................................................................................................................... 61 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 66 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

SOUHRNNÁ TERITORIÁLNÍ INFORMACE Čína

SOUHRNNÁ TERITORIÁLNÍ INFORMACE Čína Souhrnná teritoriální informace Čína Zpracováno a aktualizováno zastupitelským úřadem ČR v Pekingu (Čína) ke dni 13. 8. 2020 3:17 Seznam kapitol souhrnné teritoriální informace: 1. Základní charakteristika teritoria, ekonomický přehled (s.2) 2. Zahraniční obchod a investice (s.15) 3. Vztahy země s EU (s.28) 4. Obchodní a ekonomická spolupráce s ČR (s.30) 5. Mapa oborových příležitostí - perspektivní položky českého exportu (s.39) 6. Základní podmínky pro uplatnění českého zboží na trhu (s.46) 7. Kontakty (s.81) 1/86 http://www.businessinfo.cz/cina © Zastupitelský úřad ČR v Pekingu (Čína) SOUHRNNÁ TERITORIÁLNÍ INFORMACE Čína 1. Základní charakteristika teritoria, ekonomický přehled Podkapitoly: 1.1. Oficiální název státu, složení vlády 1.2. Demografické tendence: Počet obyvatel, průměrný roční přírůstek, demografické složení (vč. národnosti, náboženských skupin) 1.3. Základní makroekonomické ukazatele za posledních 5 let (nominální HDP/obyv., vývoj objemu HDP, míra inflace, míra nezaměstnanosti). Očekávaný vývoj v teritoriu s akcentem na ekonomickou sféru. 1.4. Veřejné finance, státní rozpočet - příjmy, výdaje, saldo za posledních 5 let 1.5. Platební bilance (běžný, kapitálový, finanční účet), devizové rezervy (za posledních 5 let), veřejný dluh vůči HDP, zahraniční zadluženost, dluhová služba 1.6. Bankovní systém (hlavní banky a pojišťovny) 1.7. Daňový systém 1.1 Oficiální název státu, složení vlády Čínská lidová republika (Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo; zkráceně Zhongguo) Úřední jazyk čínština (Putonghua, standardní čínština založená na pekingském dialektu), dále jsou oficiálními jazyky kantonština v provincii Guangdong, mongolština v AO Vnitřní Mongolsko, ujgurština a kyrgyzština v AO Xinjiang, tibetština v AO Xizang (Tibet). Složení vlády • Prezident: Xi Jinping (v úřadu od 14. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

The Long Shadow of a Fiscal Expansion

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE LONG SHADOW OF A FISCAL EXPANSION Chong-En Bai Chang-Tai Hsieh Zheng Michael Song Working Paper 22801 http://www.nber.org/papers/w22801 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 November 2016 We thank the editors of the Brookings Papers, Maury Obstfeld, and Linda Tesar for extremely helpful comments. We also thank Xueting Wen for excellent research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2016 by Chong-En Bai, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Michael Song. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. The Long Shadow of a Fiscal Expansion Chong-En Bai, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Michael Song NBER Working Paper No. 22801 November 2016 JEL No. E0 ABSTRACT In 2009 and 2010, China undertook a 4 trillion Yuan fiscal stimulus, roughly equivalent to 12 percent of annual GDP. The "fiscal" stimulus was largely financed by off-balance sheet companies (local financing vehicles) that borrowed and spent on behalf of local governments. The off-balance sheet financial institutions continued to grow after the stimulus program ended at the end of 2010. After the end of the stimulus program, spending by these off-balance sheet companies accounted for roughly 10% of GDP each year, with an increasing share used for what are essentially private commercial projects. -

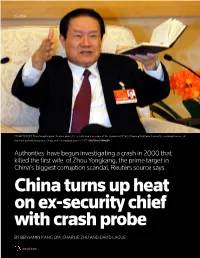

China Turns up Heat on Ex-Security Chief with Crash Probe

CHINA PRIME TARGET: Zhou Yongkang was head of domestic security and a member of the Communist Party Standing Politburo Committee, making him one of the most powerful people in China, until he stepped down in 2012. REUTERS/STRINGER Authorities have begun investigating a crash in 2000 that killed the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, the prime target in China’s biggest corruption scandal, Reuters source says. China turns up heat on ex-security chief with crash probe BY BENJAMIN KANG LIM, CHARLIE ZHU AND DAVID LAGUE SPECIAL REPORT 1 CHINA’S POWER STRUGGLE BEIJING/HONG KONG, SEPTEMBER 12, 2014 ittle is known about the exact circum- stances in which Wang Shuhua was Lkilled. What has been reported, in the Chinese media, is that she died in a road ac- cident sometime in 2000, shortly after she was divorced from her husband. And that at least one vehicle with a military license plate may have been involved in the crash. Fourteen years later, investigators are looking into her death. Their sudden inter- est has nothing to do with Wang herself. It has to do with the identity of her ex-hus- band – once one of China’s most powerful men and now the prime target in President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign. Investigators are probing the death of the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, China’s HUNTING TIGERS: President Xi Jinping has launched the biggest corruption crackdown since the retired security czar, a source with di- communists came to power in 1949, going after “tigers” or high-ranking officials as well as “flies”. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

China's Domestic Politicsand

China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China edited by Jung-Ho Bae and Jae H. Ku China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China 1SJOUFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFE %FDFNCFS 1VCMJTIFECZ ,PSFB*OTUJUVUFGPS/BUJPOBM6OJGJDBUJPO ,*/6 1VCMJTIFS 1SFTJEFOUPG,*/6 &EJUFECZ $FOUFSGPS6OJGJDBUJPO1PMJDZ4UVEJFT ,*/6 3FHJTUSBUJPO/VNCFS /P "EESFTT SP 4VZVEPOH (BOHCVLHV 4FPVM 5FMFQIPOF 'BY )PNFQBHF IUUQXXXLJOVPSLS %FTJHOBOE1SJOU )ZVOEBJ"SUDPN$P -UE $PQZSJHIU ,*/6 *4#/ 1SJDF G "MM,*/6QVCMJDBUJPOTBSFBWBJMBCMFGPSQVSDIBTFBUBMMNBKPS CPPLTUPSFTJO,PSFB "MTPBWBJMBCMFBU(PWFSONFOU1SJOUJOH0GGJDF4BMFT$FOUFS4UPSF 0GGJDF China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies and Major Countries’ Strategies toward China �G 1SFGBDF Jung-Ho Bae (Director of the Center for Unification Policy Studies at Korea Institute for National Unification) �G *OUSPEVDUJPO 1 Turning Points for China and the Korean Peninsula Jung-Ho Bae and Dongsoo Kim (Korea Institute for National Unification) �G 1BSUEvaluation of China’s Domestic Politics and Leadership $IBQUFS 19 A Chinese Model for National Development Yong Shik Choo (Chung-Ang University) $IBQUFS 55 Leadership Transition in China - from Strongman Politics to Incremental Institutionalization Yi Edward Yang (James Madison University) $IBQUFS 81 Actors and Factors - China’s Challenges in the Crucial Next Five Years Christopher M. Clarke (U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research-INR) China’s Domestic Politics and Foreign Policies -

Issue 1 2013

ISSUE 1 · 2013 NPC《中国人大》对外版 CHAIRMAN ZHANG DEJIANG VOWS TO PROMOTE SOCIALIST DEMOCRACY, RULE OF LAW ISSUE 4 · 2012 1 Chairman of the NPC Standing Committee Zhang Dejiang (7th, L) has a group photo with vice-chairpersons Zhang Baowen, Arken Imirbaki, Zhang Ping, Shen Yueyue, Yan Junqi, Wang Shengjun, Li Jianguo, Chen Changzhi, Wang Chen, Ji Bingxuan, Qiangba Puncog, Wan Exiang, Chen Zhu (from left to right). Ma Zengke China’s new leadership takes 6 shape amid high expectations Contents Special Report Speech In–depth 6 18 24 China’s new leadership takes shape President Xi Jinping vows to bring China capable of sustaining economic amid high expectations benefits to people in realizing growth: Premier ‘Chinese dream’ 8 25 Chinese top legislature has younger 19 China rolls out plan to transform leaders Chairman Zhang Dejiang vows government functions to promote socialist democracy, 12 rule of law 27 China unveils new cabinet amid China’s anti-graft efforts to get function reform People institutional impetus 15 20 28 Report on the work of the Standing Chairman Zhang Dejiang: ‘Power China defense budget to grow 10.7 Committee of the National People’s should not be aloof from public percent in 2013 Congress (excerpt) supervision’ 20 Chairman Zhang Dejiang: ‘Power should not be aloof from public supervision’ Doubling income is easy, narrowing 30 regional gap is anything but 34 New age for China’s women deputies ISSUE 1 · 2013 29 37 Rural reform helps China ensure grain Style changes take center stage at security Beijing’s political season 30 Doubling -

Confucianism, "Cultural Tradition" and Official Discourses in China at the Start of the New Century

China Perspectives 2007/3 | 2007 Creating a Harmonious Society Confucianism, "cultural tradition" and official discourses in China at the start of the new century Sébastien Billioud Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/2033 DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.2033 ISSN : 1996-4617 Éditeur Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 septembre 2007 ISSN : 2070-3449 Référence électronique Sébastien Billioud, « Confucianism, "cultural tradition" and official discourses in China at the start of the new century », China Perspectives [En ligne], 2007/3 | 2007, mis en ligne le 01 septembre 2010, consulté le 14 novembre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/2033 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.2033 © All rights reserved Special feature s e v Confucianism, “Cultural i a t c n i e Tradition,” and Official h p s c r Discourse in China at the e p Start of the New Century SÉBASTIEN BILLIOUD This article explores the reference to traditional culture and Confucianism in official discourses at the start of the new century. It shows the complexity and the ambiguity of the phenomenon and attempts to analyze it within the broader framework of society’s evolving relation to culture. armony (hexie 和谐 ), the rule of virtue ( yi into allusions made in official discourse, we are interested de zhi guo 以德治国 ): for the last few years in another general and imprecise category: cultural tradi - Hthe consonance suggested by slogans and tion ( wenhua chuantong ) or traditional cul - 文化传统 themes mobilised by China’s leadership has led to spec - ture ( chuantong wenhua 传统文化 ). ((1) However, we ulation concerning their relationship to Confucianism or, are excluding from the domain of this study the entire as - more generally, to China’s classical cultural tradition. -

Reform in Deep Water Zone: How Could China Reform Its State- Dominated Sectors at Commanding Heights

Reform in Deep Water Zone: How Could China Reform Its State- Dominated Sectors at Commanding Heights Yingqi Tan July 2020 M-RCBG Associate Working Paper Series | No. 153 The views expressed in the M-RCBG Associate Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business & Government or of Harvard University. The papers in this series have not undergone formal review and approval; they are presented to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business & Government Weil Hall | Harvard Kennedy School | www.hks.harvard.edu/mrcbg 1 REFORM IN DEEP WATER ZONE: HOW COULD CHINA REFORM ITS STATE-DOMINATED SECTORS AT COMMANDING HEIGHTS MAY 2020 Yingqi Tan MPP Class of 2020 | Harvard Kennedy School MBA Class of 2020 | Harvard Business School J.D. Candidate Class of 2023 | Harvard Law School RERORM IN DEEP WATER ZONE: HOW COULD CHINA REFORM ITS STATE-DOMINATED SECTORS AT COMMANDING HEIGHTS 2 Contents Table of Contents Contents .................................................................................................. 2 Acknowledgements ................................................................................ 7 Abbreviations ......................................................................................... 8 Introduction ......................................................................................... -

People's Republic of China

PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA NINE YEARS AFTER TIANANMEN - STILL A “COUNTER-REVOLUTIONARY RIOT" ? INTRODUCTION The 4th of June 1998 will mark the ninth anniversary of the massacre of hundreds of unarmed civilians in Beijing on 4 June 1989, when heavily armed troops and hundreds of armoured military vehicles stormed into the city to clear the streets of pro-democracy demonstrators, firing at onlookers and protesters in the process. In the aftermath of the massacre, thousands of people were detained throughout China. Some received long sentences and are still imprisoned. Amnesty International maintains records of over 250 people who are still imprisoned in connection with the 1989 pro-democracy protests and believes the real number is much higher than the cases it has identified. Every year, new cases of political prisoners imprisoned since 1989 have come to light. Nine years after the massacre and the massive arrests which followed, the Chinese authorities still appear unwilling to reassess the official “verdict” passed at the time that the protests were a “counter-revolutionary riot”. So far, the authorities have taken no step to publicly investigate the killings and bring to justice those found responsible for human rights violations, or to review the cases of those still imprisoned for their activities during the protests. This official “verdict” was used in 1989 to justify the brutal suppression of the protests, despite clear evidence that the seven-weeks protests, starting in mid-April 1989, were overwhelmingly peaceful and drew wide popular support. Several million people took part in the demonstrations, demanding an end to official corruption and calling for political reforms. -

China's Zhu Says Japan Visit Was, “Full of Achievements”

12800 11/2/00 6:29 AM Page 1 Japan Information and Culture Center, EMBASSY OF JAPAN CHINA’S ZHU SAYS JAPAN VISIT WAS, “FULL OF ACHIEVEMENTS” Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji declared his six-day trip to Japan from Oct. 12-17 a success, saying that his talks with Prime Minister Yoshiro Mori and other officials were “full of achievements.” He said the two sides found ways to “deepen C mutual understanding,” and were able to “gain common views.” On his arrival, the Premier said, “The development of China-Japan ties will have an important impact not only on the interests of the two countries and their peoples but on the peace, stability and prosperity of the Asia-Pacific region.” The two sides discussed a range of issues from trade to regional security to development assistance, and they also agreed to set up an emergency hotline between Tokyo and Beijing. At a banquet in his honor hosted by Prime Minister Mori, the Premier said, “There are great changes going on in regional and global affairs, but there should be no change in the friendship between China and Japan, and even more, no change in the goal of both peoples seeking friendly OCT 2 0 0 0 ties for generations to come.” In response the Prime Minister noted that 10 the two countries are neighbors, “But we must try harder to build a CONTENTS genuine partnership.” Mr. Mori accepted an invitation extended by Premier Zhu to visit China next year. Furthermore, the two leaders News Digest agreed to hold a tripartite summit meeting, between Japan, the Concern at Mideast violence; Yugoslavia’s Republic of Korea and China, on the occasion of the ASEAN+3 election; a dialogue with Africa.