Complete Issue As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Domain & Hosting Industry Insight from a UAE Hosting

MENOG 2015 – Dubai – 1st April 2015 Domain & Hosting Industry Insight from a UAE hosting company - AEserver Presented by Munir Badr Founder/CEO Agenda 1. About the speaker 2. Domain name industry review - UAE/Qatar domains - Rest of the GCC region - ICANN registrars 3. Web hosting market review - Hosting business in UAE - Common challenges 4. Improvements over time/positive change About Munir Badr / AEserver • Dubai based internet entrepreneur. UAE resident since 1996 and Engineering graduate from American University of Sharjah • Dubai based startup in 2005. Registered as a company in 2008. • Started as a reseller of .AE domain names through the local ISP + Web Hosting • TRA formed aeDA in 2008 to change the regime – registry- registrar model launched – we applied for accreditation (.ae) • Hosting: Local (Dubai) + offshore (EU, USA) hosting • Signed up with ictQatar for .QA accreditation in 2013 Domain Market Review - UAE • National country code: .AE (IDN: emarat) - Over 124,000 domains registered as of December 2014 • Registry: aeDA – part of TRA, operates registry-registrar model (since 2008). Clear well written and transparent policy. • 2nd level domains are open to the whole world – no restrictions • 3rd level domains are restricted and require docs • Very popular domain name, used by most business and international brands. • 22 accredited registrars (local and international) and most offer instant registration via EPP • Domain after market exists and boasts high value sales Domain Market Review - Qatar • National country code: .QA (IDN: .qatar) - Over 19,500+ domains registered as of today • Registry: Communications Regulatory Authority (CRA), operates registry-registrar model (since 2013). Clear well written and transparent policy • 2nd level domains are open to the whole world – no restrictions • 3rd level domains are restricted and require docs • Popular domain name, used by most business and international brands. -

Eurid-UNESCO World Report on Internationalised Domain Names Deployment 2012

EURid-UNESCO World report on Internationalised Domain Names deployment 2012 The World report on Internationalised Domain Names deployment updates the EURid-UNESCO Internationalised Domain Names State of Play report 2011. This year, the data set includes 88 TLDs, compared with 55 in 2011. The report also looks at deployment experiences of IDN ccTLDs in selected regions and explores opportunities and challenges for IDN deployment going forward. 3 Файл загружен с http://www.ifap.ru Contents FOREWORD by VINTON G. CERF ..........................................06 ExECUTIVE SUmmaRy .....................................................09 GLOSSaRy OF TERmS .....................................................12 INTRODUCTION ............................................................15 PART 1: DEPLOYMENT OF IDNS 1 WhaT aRE INTERNaTIONaLISED DOmaIN NamES, aND Why aRE ThEy ImPORTaNT? ...............................17 2 IDN TImELINE ..............................................................19 3 LINk WITh LOCaL LaNGUaGE .............................................22 4 ThE IDN USER ExPERIENCE: EmaIL aND WEb bROWSERS ...............22 4.1 Email functionality .............................................................22 4.2 IDNs in web browsers ........................................................23 5 NEW IDN gTLDS? ..........................................................25 6 aDOPTION OF IDNS – UPDaTE .............................................28 6.1 Deployment at the second level .............................................28 6.2 Growth -

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

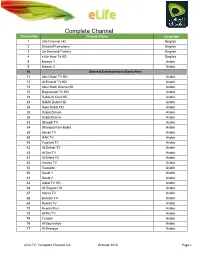

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

Arabic, Chinese and Cyrillic Script Top-Level Domain Names Undrah Baasanjav [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Edwardsville SPARK SIUE Faculty Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activity Winter 12-15-2014 Linguistic Diversity on the Internet: Arabic, Chinese and Cyrillic Script Top-Level Domain Names Undrah Baasanjav [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://spark.siue.edu/siue_fac Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, International and Intercultural Communication Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Baasanjav, Undrah, "Linguistic Diversity on the Internet: Arabic, Chinese and Cyrillic Script Top-Level Domain Names" (2014). SIUE Faculty Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activity. 71. https://spark.siue.edu/siue_fac/71 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SPARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in SIUE Faculty Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activity by an authorized administrator of SPARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Telecommunications Policy 38 (2014) 961–969 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Telecommunications Policy URL: www.elsevier.com/locate/telpol Linguistic diversity on the internet: Arabic, Chinese and Cyrillic script top-level domain names Undrah B. Baasanjav n Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, USA article info abstract Available online 20 May 2014 The deployment of Arabic, Chinese, and Cyrillic top-level domain names is explored in this Keywords: research by analyzing technical and policy documents of the Internet Corporation for International domain names Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), as well as newspaper articles in the respective IDN language regions. The tension between English uniformity at the root level of the Language diversity Internet's domain names system, and language diversity in the global Internet commu- Country-code TLD nity, has resulted in various technological solutions surrounding Arabic, Chinese, and ICANN Cyrillic language domain names. -

2014 Retail Foods Sector Retail Foods Egypt

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 7/21/2015 GAIN Report Number: Egypt Retail Foods 2014 Retail Foods Sector Approved By: Ron Verdonk Prepared By: Orestes Vasquez Ibrahim Mohamed Report Highlights: This report provides U.S. exporters of consumer-ready food products with an overview of the Egyptian retail foods sector. Best product prospects are included in this report. Best prospects for U.S. products are beef livers and offal, dairy products and tree nuts. Apples and snack foods growth rates have decreased due to Egypt’s free trade agreement with the EU, as European products enjoy preferential tariff rates. In 2014, U.S. exports of value-added food product exports to Egypt were valued at $315 million. Disclaimer: This report was prepared by the Foreign Agricultural Service in Cairo for U.S. exporters of food and agricultural products, as well as U.S. regulatory agencies. While care was taken in the preparation of this report, information provided may not be completely accurate due to either recent policy changes or because clear and consistent information about some policies is unavailable. It is strongly recommended that U.S. exporters verify all Egyptian import requirements with their foreign customers prior to the shipment of goods. Final import approval of any product is subject to the importing country’s rules and regulations. Post: Cairo Executive Summary: In the last five years Egypt’s food retail market has grown at an average annual rate of 19 percent. -

Governorate Area Type Provider Name Card Specialty Address Telephone 1 Telephone 2

Governorate Area Type Provider Name Card Specialty Address Telephone 1 Telephone 2 Metlife Clinic - Cairo Medical Center 4 Abo Obaida El bakry St., Roxy, Cairo Heliopolis Metlife Clinic 02 24509800 02 22580672 Hospital Heliopolis Emergency- 39 Cleopatra St. Salah El Din Sq., Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Cleopatra Hospital Gold Outpatient- 19668 Heliopolis Inpatient ( Except Emergency- 21 El Andalus St., Behind Cairo Heliopolis Hospital International Eye Hospital Gold 19650 Outpatient-Inpatient Mereland , Roxy, Heliopolis Emergency- Cairo Heliopolis Hospital San Peter Hospital Green 3 A. Rahman El Rafie St., Hegaz St. 02 21804039 02 21804483-84 Outpatient-Inpatient Emergency- 16 El Nasr st., 4th., floor, El Nozha Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Ein El Hayat Hospital Green 02 26214024 02 26214025 Outpatient-Inpatient El Gedida Cairo Medical Center - Cairo Heart Emergency- 4 Abo Obaida El bakry St., Roxy, Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Silver 02 24509800 02 22580672 Center Outpatient-Inpatient Heliopolis Inpatient Only for 15 Khaled Ibn El Walid St. Off 02 22670702 (10 Cairo Heliopolis Hospital American Hospital Silver Gynecology and Abdel Hamid Badawy St., Lines) Obstetrics Sheraton Bldgs., Heliopolis 9 El-Safa St., Behind EL Seddik Emergency - Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Nozha International Hospital Silver Mosque, Behind Sheraton 02 22660555 02 22664248 Inpatient Only Heliopolis, Heliopolis 91 Mohamed Farid St. El Hegaz Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Al Dorrah Heart Care Hospital Orange Outpatient-Inpatient 02 22411110 Sq., Heliopolis 19 Tag El Din El Sobky st., from El 02 2275557-02 Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Egyheart Center Orange Outpatient 01200023220 Nozha st., Ard El Golf, Heliopolis 22738232 2 Samir Mokhtar st., from Nabil El 02 22681360- Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Egyheart Center Orange Outpatient 01200023220 Wakad st., Ard El Golf, Heliopolis 01225320736 Dr. -

Opening Statement by ROD BECKSTROM President

Opening Statement by ROD BECKSTROM President and Chief Executive Officer Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) Launch of UAE’S Internationalized Domain Name Abu Dhabi 26 May 2010 As prepared for delivery Thank you for inviting me to join you on this historic day. Thanks especially to Mr. Mohamed Nasser Al-Ghanim, Director General of the Telecom Regulatory Authority (TRA), for his dedication to bringing this achievement to fruition. The United Arab Emirates is one of the first four countries in the history of the Internet to secure an internationalized top level domain name, allowing people whose primary language script is Arabic to access websites entirely with Arabic characters. This achievement is a reflection of UAE’s forward thinking and visionary leadership. The Internet is the way of the future, and the UAE has recognized and embraced that future in pursuing this IDN on behalf of its people. ICANN works toward a common good – a stable and secure global Internet. It keeps the Internet running by maintaining the security and stability of the domain name system to keep the Internet unified. And it is a multi-stakeholder, multinational institution overseen “by the world, for the world”, reflecting its increasingly global work. A truly global Internet means that anyone can connect to anyone anywhere. Our economies, our communications, our social and cultural lives are linked by the Internet – the most powerful communications tool in the history of mankind. And for many millions, the introduction of IDNs means they can do so in their primary language. Five of the top ten languages in use on the Internet today rely on a non-Latin script: Chinese, Japanese, Arabic, Russian and Korean, in roughly descending order. -

SUSTAINABILITY INDEPENDENT MEDIA in the Middle East INDEX and North Africa 2009 MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2009

algeria egypt iraq jordan bahrain kuwait lebanon morocco libya oman palestine united arab emirates saudi arabia syria iraq-kurdistan tunisia iran qatar yemen DEVELOPMENT MEDIA OF SUSTAINABLE SUSTAINABILITY INDEPENDENT MEDIA IN THE MIDDLE EAST INDEX AND NORTH AFRICA 2009 MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2009 The Development of Sustainable Independent Media in the Middle East and North Africa MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2009 The Development of Sustainable Independent Media in the Middle East and North Africa www.irex.org/msi Copyright © 2011 by IREX IREX 2121 K Street, NW, Suite 700 Washington, DC 20037 E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (202) 628-8188 Fax: (202) 628-8189 www.irex.org Project manager: Leon Morse Assistant editor: Dayna Kerecman Myers Copyeditors: Carolyn Feola de Rugamas, Carolyn.Ink; Kelly Kramer, WORDtoWORD Editorial Services; OmniStudio Design and layout: OmniStudio Printer: Westland Enterprises, Inc. Notice of Rights: Permission is granted to display, copy, and distribute the MSI in whole or in part, provided that: (a) the materials are used with the acknowledgement “The Media Sustainability Index (MSI) is a product of IREX with funding from USAID.”; (b) the MSI is used solely for personal, noncommercial, or informational use; and (c) no modifications of the MSI are made. Acknowledgment: This publication was made possible through support provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under Cooperative Agreement No. #DFD-A-00-05-00243 (MSI-MENA) via a Task Order by the Academy for Educational Development. Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein are those of the panelists and other project researchers and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or IREX. -

World Report on Internationalised Domain Names 2014

.eu Insights World report on Internationalised Domain Names 2014 August 2014 With the support of With the support of CENTR, LACTLD, APTLD, and AFTLD .eu Insights The EURid Insights series aims to analyse specifc aspects of the domain name environment. The reports are based on surveys, studies and research conducted by EURid in cooperation with industry experts and sector leaders. World report on Internationalised Domain Names 2014 Numbers (December 2013) 6 2% 215% Million of the world’s growth IDN domain names 270 million domain in the IDN market over names are IDNs the past 5 years 2012-2013 116% IDN.IDN 46% -8% ccTLD annual gTLD IDN ccTLD IDNs growth rate annual growth rate annual growth rate (second level) (second level) 50 26 2 ASCII TLDs IDNs IDN gTLDs offer IDNs at the sec- for 22 countries or territories (web), ond level (eg .com, .eu) (eg , ) (everyone) Languages • IDNs help to enhance multilingualism in cyberspace • The IDN market is more balanced in favour of emerging economies • IDNs are accurate predictors of the language of online content • 99%+ correlation between IDN scripts and language of website • Strong correlation between country of hosting and IDN scripts • Japanese, Chinese, Korean and German are the most popular languages for content associated with IDNs • Arabic script IDNs are associated with blogs, ecommerce and online business sites in Persian and Arabic language Universal acceptance • Universal acceptance of IDNs the key challenge to mass uptake • Google Gmail began supporting internationalised email addresses starting in July 2014. Popular open source email services are also supporting IDN emails • Standardised programming tools for mobile application developers support IDNs • Social media and search have improved support for IDNs as URLs in links • Universal acceptance is a wider issue than previously thought. -

EMIRATES (Incorporated with Limited Liability Under the Laws of Dubai)

Level: 4 – From: 4 – Thursday, June 2, 2011 – 11:14 – eprint6 – 4324 Intro PROSPECTUS EMIRATES (incorporated with limited liability under the laws of Dubai) U.S.$1,000,000,000 5.125 per cent. Notes due 2016 Issue Price 99.904 per cent. U.S.$1,000,000,000 5.125 per cent. Notes due 2016 (the “Notes”) will be issued by Emirates (the “Issuer” or “Emirates”). Interest on the Notes is payable semi-annually in arrear on 8 June and 8 December in each year. Payments on the Notes will be made without deduction for or on account of taxes of the United Arab Emirates and the Emirate of Dubai to the extent described under “Terms and Conditions of the Notes – Taxation”. The Notes mature on 8 June 2016 but the Notes may be redeemed before maturity at the option of the Issuer in whole but not in part at their principal amount together with accrued interest at any time in the event of certain changes affecting taxes of the United Arab Emirates and/or the Emirate of Dubai, and may also be redeemed before maturity at the option of the relevant holder at their principal amount together with accrued interest following a Change of Control (as defined in the Terms and Conditions). See “Terms and Conditions of the Notes – Redemption and Purchase”. The Notes, subject to Condition 4 (Negative Pledge), will constitute unsecured obligations of the Issuer. See “Ter ms and Conditions of the Notes – Status”. Application has been made to the Financial Services Authority in its capacity as competent authority under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (the “FSMA”) (the “UK Listing Authority”) for the Notes to be admitted to the official list of the UK Listing Authority (the “Official List”) and to the London Stock Exchange plc (the “London Stock Exchange”) for such Notes to be admitted to trading on the London Stock Exchange’s Regulated Market (the “Market”). -

Globeland30 Maps Show Four Times Larger Gross Than Net Land Change from 2000 to 2010 in Asia T

Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinformation 78 (2019) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinformation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jag GlobeLand30 maps show four times larger gross than net land change from 2000 to 2010 in Asia T ⁎ Hossein Shafizadeh-Moghadama, Masoud Minaeib, Yongjiu Fengc, Robert Gilmore Pontius Jr.d, a Department of GIS and Remote Sensing, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran b Department of Geography, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran c College of Surveying and Geo-informatics, Tongji University, Shanghai, 200092, China d School of Geography, Clark University, 950 Main Street, Worcester, MA, 01610, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: This article uses the GlobeLand30 maps of land cover to characterize the difference between years 2000 and Asia 2010 in Asia. Methods of Intensity Analysis and Difference Components dissect the transition matrix for nine GlobeLand30 categories: Barren, Grass, Cultivated, Forest, Shrub, Water, Artificial, Wetland and Ice. Results show that Barren, Intensity analysis Grass, Cultivated, and Forest each account for more than 21% of Asia at both 2000 and 2010, while transitions Land cover change among those four categories account for more than half of the temporal difference. Nearly ten percent of Asia Land degradation shows overall temporal difference, which is the sum of three components: quantity, exchange and shift. Quantity Urbanization accounts for less than a quarter of the temporal difference, while exchange accounts for three quarters of the temporal difference. The largest quantity components at the category level are a net gain of Barren and net losses of Grass and Shrub. -

TRA/Aeda Background

TRA/aeDA Background The aeDA was established in 2007 by the Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of UAE (TRA) as a department. It is the Regulatory Body and Registry Operator for the .ae domain name. The aeDA is responsible for the setting and enforcement of all policies with regard to the operation of the .ae ccTLD as well as overseeing the operation of the Registry System. The aeDA’s role is to: Develop and execute policy Grow, develop and market the .ae namespace Accredit and manage .ae Registrars Educate the public, delivering and promoting the .ae domain name Facilitate the .ae Dispute Resolution Policy Represent .ae at International Forums As the aeDA has been formed by the TRA, a federal government department, the aeDA will continually strive to maintain best practice for the administration of the .ae ccTLD and will administer the .ae domain in a fair and transparent manner. Changes in the Technical Operation of the .ae ccTLD: The aeDA brought changes to the ae ccTLD in order to bring it in line with international best practices. The aeDA introduced the ‘Registry - Registrar Model’ into the .ae ccTLD, to provide clarity of the roles within the industry, and to introduce competitive pricing, and service models for Registrants. .ae Registry-Registrar Model The roles of aeDA Industry are as follows: Regulatory Body – aeDA The organisation vetted with the responsibility of operating the ccTLD for the benefit of all stakeholders. Registry Operator – aeDA Has the exclusive responsibly for maintenance of a centralised Registry for its particular TLD. The Regulatory Body and Registry Operator in some instances may be separate organisations, however in the case of the .ae ccTLD, the aeDA will assume both roles.