Transforming Future Governance of Extractive Industries in Asean: Framework, Opportunities and Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Age Assessment in People Smuggling Cases

Submission to AHRC Inquiry: Age Assessment in People Smuggling cases Submission Author: Greg HOGAN Submission Date: 3 February 2012 source: http://chrocodiles.blogspot.com/2010/11/wonderful-indonesian-culture-of-shadow.html Contents Pages Prologue: Why I make a Submission? 2 - 3 Catchwords for this Submission 4 Background: People-Smuggling Prosecutions 5 - 6 Introduction: Location, Fisheries & Montara 7 - 10 Response to the Inquiry’s Terms of Reference 11 – 36 Appendix A: Case Law 37 – 40 Appendix B: References 41 – 50 Appendix C: Glossary of Selected Terms 51 – 54 Submission by Greg HOGAN Page 1 of 54 Submission to AHRC Inquiry: Age Assessment in People Smuggling cases PROLOGUE: My submission will address the Inquiry’s Terms of Reference. It is sourced from published research related to the subject-matter of the Inquiry and, includes personal Why I make a observation of information made public in open court in 2011, during the district court Submission? trials of Indonesian crew charged with people-smuggling offences. This Inquiry - into the treatment of individuals suspected of people-smuggling offences who say they are children - needs however to appreciate the way in which the Indonesian crew are organised onto the ‘perahu layar motor’ (PLM Type III) boats People destined for Australia’s northern waters. It is important to understand that these Smugglers’ voyages comprise two legs – the longer 1st leg eastwards across the Indonesian modus operandi archipelago and the short 2nd leg beginning off Pulau Roti directly due south 60 nautical miles (110 km) overnight to Ashmore reef. See Map 1. The number of Indonesian crew that embark is almost invariably less than the number of crew upon intercept at Ashmore reef. -

The Unacceptable Risks of Oil Exploration

Oil or Gas Production in the Great Australian Bight Submission 43 DANGER IN OUR SEAS: THE UNACCEPTABLE RISKS OFL O EI XPLORATION AND PRODUCTION IN THE GREAT AUSTRALIAN BIGHT Submission into the Inquiry by the Australian Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications into Oil and Gas Production in the Great Australian Bight APRIL 2016 Oil or Gas Production in the Great Australian Bight Submission 43 Senate Inquiry Submission: Danger in our Seas April 2016 Terms of Reference to the Senate Inquiry The Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications established an Inquiry into Oil and Gas Production in the Great Australian Bight on 22 February 2016. The Committee will consider and report on the following: The potential environmental, social and economic impacts of BP’s planned exploratory oil drilling project, and any future oil or gas production in the Great Australian Bight, with particular reference to: a. the effect of a potential drilling accident on marine and coastal ecosystems, including: i. impacts on existing marine reserves within the Bight ii. impacts on whale and other cetacean populations iii. impacts on the marine environment b. social and economic impacts, including effects on tourism, commercial fishing activities and other regional industries c. current research and scientific knowledge d. the capacity, or lack thereof, of government or private interests to mitigate the effect of an oil spill e. any other related matters. Map of the Great Australian Bight and granted oil and gas exploration permits, with companies holding ownership of the various permits shown. The Wilderness Society recognises that the Great Australian Bight is an Indigenous cultural domain, and of enormous value to its Traditional Owners who retain living cultural, spiritual, social and economic connections to their homelands within the region on land and sea. -

Bab 3 Maka Dapat Ditarik Kesimpulan

72 BAB IV KESIMPULAN DAN SARAN 4.1. Kesimpulan Dari berbagai bahasan yang telah diuraikan pada Bab 1- Bab 3 maka dapat ditarik kesimpulan : 1. Adanya kekosongan hukum yang jelas mengenai pengeboran minyak lepas pantai yang perlu diisi dalam perkembangan hukum internasional. Kovensi internasional seperti UNCLOS memang memberikan tanggung jawab pada pesertanya sebagian besar dalam hal pencegahan, tindakan penanganan serta keejasama antarnegara. Namun konvensi konvensi ini tidak dengan secara jelas menjelaskan mengenai masalah pertanggung jawaban. 2. Keputusan Pemerintah Indonesia yang memilih jalur diplomatik tidak dapat menemukan penyelesaian sehingga akhirnya rakyat Timor memilih melakukan gugatan class action di Pengadilan Federal Australia. Gugatan ini bisa dilakukan karena ada bantuan besar dari Greg Phelps. Ia adalah Partner di Law-Firm Ward Keller Darwin Australia dan ia juga pernah menjadi President dari Australia Lawyers Alliance. Gugatan yang diajukan rakyat NTT terkait dengan pencemaran ini baru sebatas pada nelayan rumput laut karena mereka memiliki lahan sehingga bisa dibuktikan secara nyata. Dari 12 kabupaten yang terkena dampak pencemaran Laut Timor itu, baru petani rumput laut dari dua kabupaten, yakni Rote dan Kupang, yang diajukan ke Pengadilan Federal Australia. Jumlah korbannya mencapai 13 ribu orang. 73 Didalam bidang hukum yang menyangkut kepentingan publik, lembaga class action mempunyai kedudukan yang strategis. Strategis dalam arti memberikan akses yang lebih besar bagi masyarakat terutama yang kurang mampu baik secara ekonomis maupun structural untuk menentukan apa yang menjadi hak mereka yang bersifat public, misalnya hak atas kesehatan dan hak atas lingkungan hidup yang bersih dan sehat. Gugatan ini dilayangkan di Australia karena Australia sebagai regulator di kawasan tersebut dan bila terjadi pencemaran dan ada masyarakat yang terkena dampak nya baik masyarakat Australia atau warga yang lain yang penting ia terkena dampaknya/merasa dirugikan maka ia bisa mengajukan gugatan di sana. -

Budhi Gunadharma Gautama Oil-Spill Monitoring in Indonesia

THÈSE / IMT Atlantique Présentée par sous le sceau de l’Université Bretagne Loire Budhi Gunadharma Gautama pour obtenir le grade de Préparée dans le département Signal & communications DOCTEUR D'IMT Atlantique Spécialité : Signal, Image, Vision Laboratoire Labsticc École Doctorale Mathématiques et STIC Thèse soutenue le 01 décembre 2017 devant le jury composé de : Oil-Spill Monitoring in Indonesia René Garello Professeur (HDR), IMT Atlantique / président Thomas Corpetti Directeur de recherche (HDR), LETG-Rennes / rapporteur Serge Andrefouet Directeur de recherche (HDR), INDESO Center JI. Baru Perancak / rapporteur Nicolas Longepe Chercheur, CLS – Plouzané / examinateur Emina Mamaca Chercheur, Ifremer – Plouzané examinatrice Ronan Fablet Professeur (HDR), IMT Atlantique / directeur de thèse N◦ d’ordre : 2017telb0422 Sous le sceau de l’Université Européenne de Bretagne IMT Atlantique Bretagne-Pays de la Loire En accréditation conjointe avec l’École Doctorale – SICMA Thèse de Doctorat Mention : STIC – Sciences et Technologies de l’Information et des Communications Oil Spill Observation in Indonesia présentée par Budhi Gunadharma GAUTAMA Unité de recherche : IMT Atlantique – Signal et Communication Laboratoire : Lab-STICC, Pôle CID, Équipe TOMS Entreprise partenaire : CLS FRANCE Directeurs de thèse : Ronan FABLET Encadrant de thèse : Grégoire MERCIER et Nicolas LONGÉPÉ Soutenue le 01 Decembre 2017 devant le jury composé de: M Thomas CORPETTI Rapporteur M. Serge ANDRÉFOUËT Rapporteur M. René GARELLO - Professeure, IMT Atlantique Examinateur Mme. Emina MAMACA Examinateur Contents Acknowledgments xi Acronyms xiii Abstract xv Résumé xvii Résumé étendu xix 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Context of the thesis .................................. 2 1.2 A brief review of INDESO Project .......................... 4 1.3 Thesis motivation and outline ............................. 6 2 Oil Spill Monitoring in Indonesia 9 2.1 Description of Indonesian waters .......................... -

Montara Oil Spill Report Finally Released

Vol. 33 No. 52 16 December 2010 Montara Oil Spill Report Finally Released After months of anticipation, and more than proposes accepting 92, noting 10, and not accepting one year after the leaking H1 well in the Montara 3 recommendations. The Government Response oil field in the Timor Sea off Western Australia’s also details actions taken by the government prior to Kimberley coastline was shut in, the report from the release of the Commission’s report. Montara Commission of Inquiry has been released to the public, along with a draft Government Response. Key actions taken by the Government to date include The spill from the H1 well, owned by Thailand- ensuring the integrity of the five remaining wells on based PTT Exploration & Production Australasia the Montara platform and initiating an independent Public Company Limited (PTTEP), was the largest in review of PTTEP’s Action Plan, due by the end of Australian history, with approximately 30,000 barrels the year, which Ferguson will use to evaluate whether (1.26 million gallons) of hydrocarbons released into PTTEP should be allowed to retain its license to the Timor Sea between August and November 2009 operate in the Montara field, as well as maintaining (see OSIR, 27 August 2009 and subsequent issues). its other interests. Australian Minister for Resources and Energy, In addition to issues with PTTEP’s practices, the Martin Ferguson, received the report in June 2010, Commission found regulatory problems, stating that but cited various reasons for delaying its release “the Northern Territory Department of Resources to the public (see OSIR, 17 September 2010). -

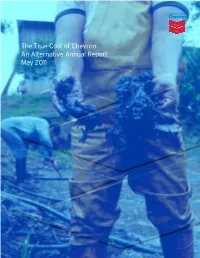

The True Cost of Chevron an Alternative Annual Report May 2011 the True Cost of Chevron: an Alternative Annual Report May 2011

The True Cost of Chevron An Alternative Annual Report May 2011 The True Cost of Chevron: An Alternative Annual Report May 2011 Introduction . 1 III . Around the World . 23 I . Chevron Corporate, Political and Economic Overview . 2. Angola . 23. Elias Mateus Isaac & Albertina Delgado, Open Society Map of Global Operations and Corporate Basics . .2 Initiative for Southern Africa, Angola The State of Chevron . .3 Australia . 25 Dr . Jill StJohn, The Wilderness Society of Western Australia; Antonia Juhasz, Global Exchange Teri Shore, Turtle Island Restoration Project Chevron Banks on a Profitable Political Agenda . .4 Burma (Myanmar) . .27 Tyson Slocum, Public Citizen Naing Htoo, Paul Donowitz, Matthew Smith & Marra Silencing Local Communities, Disenfranchising Shareholders . .5 Guttenplan, EarthRights International Paul Donowitz, EarthRights International Canada . 29 Resisting Transparency: An Industry Leader . 6. Chevron in Alberta . 29 Isabel Munilla, Publish What You Pay United States; Eriel Tchwkwie Deranger & Brant Olson, Rainforest Paul Donowitz, EarthRights International Action Network Chevron’s Ever-Declining Alternative Energy Commitment . .7 Chevron in the Beaufort Sea . 31 Antonia Juhasz, Global Exchange Andrea Harden-Donahue, Council of Canadians China . .32 II . The United States . 8 Wen Bo, Pacific Environment Colombia . 34 Chevron’s U .S . Coal Operations . 8. Debora Barros Fince, Organizacion Wayuu Munsurat, Antonia Juhasz, Global Exchange with support from Alex Sierra, Global Exchange volunteer Alaska . .9 Ecuador . 36 Bob Shavelson & Tom Evans, Cook Inletkeeper Han Shan, Amazon Watch, with support from California . 11. Ginger Cassady, Rainforest Action Network Antonia Juhasz, Global Exchange Indonesia . 39 Richmond Refinery . 13 Pius Ginting, WALHI-Friends of the Earth Indonesia Nile Malloy & Jessica Tovar, Communities for a Better Iraq . -

Offshore Petroleum Facility Incidents Post Varanus Island, Montara, and Macondo: Have We Really Addressed the Root Cause?

William & Mary Environmental Law and Policy Review Volume 2013-2014 Issue 3 Article 2 May 2014 Offshore Petroleum Facility Incidents Post Varanus Island, Montara, and Macondo: Have We Really Addressed the Root Cause? Tina Hunter Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Energy and Utilities Law Commons, Environmental Law Commons, and the Water Law Commons Repository Citation Tina Hunter, Offshore Petroleum Facility Incidents Post Varanus Island, Montara, and Macondo: Have We Really Addressed the Root Cause?, 38 Wm. & Mary Envtl. L. & Pol'y Rev. 585 (2014), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr/vol38/iss3/2 Copyright c 2014 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr OFFSHORE PETROLEUM FACILITY INCIDENTS POST VARANUS ISLAND, MONTARA, AND MACONDO: HAVE WE REALLY ADDRESSED THE ROOT CAUSE? TINA HUNTER* ABSTRACT This Article analyzes the role of offshore petroleum legislation in contributing to offshore facility integrity incidents in Australia’s offshore petroleum jurisdiction. It examines the regulatory framework that existed at the time of the Varanus Island, Montara, and Macondo facility incidents, determining that the regulatory regime contributed to each of these inci- dents. Assessing the response of the Commonwealth government to the regulatory framework existing at the time of the events, particularly the integration of well regulation as part of the National Offshore Petroleum Safety Authority’s (“NOPSA”) functions and the establishment of a national offshore regulator, this Article determines that while the integration of well management into NOPSA’s functions has been a valuable and a sig- nificant improvement. -

Sustainable Livelihoods in Traditional Fishing Villages on Rote Island, Indonesian: Providing a FRESH Start for the Next Generation

Sustainable Livelihoods in Traditional Fishing Villages on Rote Island, Indonesian: Providing a FRESH Start for the next generation Author King, Paul Gerard Published 2019-09-04 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Environment and Sc DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/871 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/387391 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Sustainable Livelihoods in Traditional Fishing Villages on Rote Island, Indonesian: Providing a FRESH Start for the next generation Paul G. King Bachelor of Arts Asian and International Studies First Class Honours Centre of Excellence Sustainable Development Indonesia School of Environment and Science Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2019 Abstract Sustainable Livelihoods in small-scale fishing villages throughout Southeast Asia is the region’s greatest poverty alleviation problem. Small-scale fisheries are frequently characterised as an occupation of last choice, and fisher folk as the poorest of all. Landlessness, few productive assets and a limited skills set for these folk gives little choice other than a marine livelihood strategy, resulting in, at best, little more than a subsistence life style. Additionally, coastal and marine social-ecological systems are fragile and vulnerable to political, social and environmental shocks. Indonesia, with a population of over 250 million people, 81,000 kilometres of coast line and thousands of small-scale fishing communities, faces seemingly unsurmountable poverty alleviation challenges. This research centres on traditional fishers of Rote Island, Indonesia, who have endured challenges to their livelihoods due to changed maritime boundaries in the Timor and Arafura Seas during the late 20th Century, resulting in them being dispossessed of their traditional fishing grounds. -

Montara Production Drilling Environment Plan Summary Technical ID: MV-HSE-D41-850436

Title: Montara Production Drilling Environment Plan Summary Technical ID: MV-HSE-D41-850436 Montara Production Drilling Environment Plan Summary Title: Montara Production Drilling Environment Plan Summary Technical ID: MV-HSE-D41-850436 TECHNICAL DOCUMENT Approval Status: APPROVED Title: Montara Production Drilling Environment Plan Summary Revision No: 2 Technical ID: MV-HSE-D41-850436 Belongs To: Montara Venture System: Drilling Technical Discipline: HSE Class: Other Sub-Class: Function: Develop and Service Well Process: Construct Service or Abandon Well Related Documents: Hard Copy Location: Volume 1 Book 5 of 6 Approver: Technical Authority: Commercial Authority: SSHE Review: Originator: Drilling & Well Services Not Required Manager General Counsel SSHE Manager Rebecca Mcgrath Ed Lintott Gavin Ryan Paul McCormick Rebecca McGrath 07/09/2017 07/09/2017 07/09/2017 Thursday, 7 September 2017 1:34:35 PM 9:14:26 AM 8:15:33 AM 8:14:44 AM Revision Revision Date Revision Remarks Originator Number 2 06-09-2017 Changes made on the request of NOPSEMA REBECCA MCGRATH 1 30-08-2017 Updated to reflect current approved EP (Montara H5-ST2 Drilling Campaign) REBECCA MCGRATH 0 24-10-2013 Environment Plan Summary GLEN NICHOLSON Title: Montara Production Drilling Environment Plan Summary Technical ID: MV-HSE-D41-850436 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 5 1.1 The Titleholder 5 2 LOCATION OF THE ACTIVITY 6 2.1 Overview and Location 6 3 DESCRIPTION OF THE ACTIVITY 7 3.1 Timing of the Activity 7 3.2 Montara Development Infrastructure 7 3.3 Drilling Activity -

On the Dynamics of Oil Spill Dispersion Off Timor Sea

International Journal of Applied Environmental Sciences ISSN 0973-6077 Volume 11, Number 4 (2016), pp. 1077-1090 © Research India Publications http://www.ripublication.com On the dynamics of Oil spill dispersion off Timor Sea A. Salim1a, A. D. Syakti 2b, A. Purwandani3c, A. Sulaiman4c aFaculty of Science and Technology, Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah, Jakarta, Indonesia. bCenter for Maritime Bioscience Studies, Institute for Research and Community Empowerment-Universitas Jendral Soedirman, Purwokerto, Indonesia. cGeostech Laboratory, Badan Pengkajian dan Penerapan Teknologi, Puspiptek Serpong, Tanggerang, Indonesia. Abstract The dynamical properties of the Montara oil spill in August 2009 in the Timor Sea is investigated. The two-dimensional numerical model of Oil Spill Analysis (SA) was used to simulate oil spill dispersion. The simulation showed that for daily period, the oil dispersion was dominated by advection processes due to tidal current. When South-East Monsoon (SEM) active the oil spill propagate into the eastern of the Timor sea until 300km long at the end of simulation. The high value of the exposure time lay on the Northern part of the Timor sea and the coast of the Roti island. The comparsion of the numerical results and SAR images was done by calculation of contaminant area show a good agreement. Keywords: numerical model, oil spill, petroleum hydrocarbon, tidal current, timor sea 1. INTRODUCTION On 21 August, 2009, a serious blow out caused the evacuation of the Montara oil platform and continual release of gas, condensate and crude oil over a ten week period. The Montara platform pollute the sea with oil 400-500 barrels per day during 74 days. -

Montara Wellhead Platform Incident

Response to the Montara Wellhead Platform Incident Report of the Incident Analysis Team March 2010 Australian Maritime Safety Authority Montara Wellhead Platform Incident - Incident Analysis Team Report Cover photograph courtesy of AMSA Response to the Montara Wellhead Platform Incident Report of the Incident Analysis Team March 2010 Report by the Incident Analysis Team into the Response by the National Plan to Combat Pollution of the Sea by Oil and Other Noxious and Hazardous Substances, to the Montara Wellhead Platform Incident. i Montara Wellhead Platform Incident - Incident Analysis Team Report CONTENTS Abbreviations and Acronyms iii Preface v Executive Summary ix 1. Incident Description 1 2. Discussion/Key Issues 6 2.1 AMSA Response Arrangements 6 2.2 AMSA Combat Agency Role 10 2.3 Responsibility for Environmental Issues 11 2.4 Cost Recovery Arrangements 15 2.5 The Australian Maritime Safety Authority Act 17 2.6 Oil Spill Contingency Plans 17 2.7 Risk Assessment 18 2.8 Use of Petroleum Industry Resources 19 2.9 Operational/Technical Issues 21 2.10 Outstanding terms of reference 22 Appendix 1 – Terms of Reference for the National Plan Incident 23 Analysis Appendix 2 – Debriefs Attended and Personnel Interviewed by the Incident Analysis Team 25 Appendix 3 – Summary of Commissioned Reviews 29 Appendix 4 – Operational and Technical issues to be referred to the National Plan Operations Group 31 ii Montara Wellhead Platform Incident - Incident Analysis Team Report ABBREViations AND ACRONYMS AEST Australian Eastern Standard Time AFMA Australian -

Montara Surveys: Final Report on Benthic Surveys at Ashmore, Cartier and Seringapatam Reefs

Environmental Study S6.4 Corals Montara Surveys: Final report on Benthic Surveys at Ashmore, Cartier and Seringapatam Reefs Authors: Andrew Heyward, Ben Radford, Kathryn Burns, Jamie Colquhoun, Cordelia Moore Contributors Paul Tinkler, Kim Brooks, Greg Suosaari, Dave Whillas, Kerryn Johns, Mark Case, Carole Lonergan, Ross Jones, Jamie Oliver Report prepared by the Australian Institute of Marine Science for PTTEP Australasia (Ashmore Cartier) Pty. Ltd. in accordance with Contract No. 000/2009/10-23 October 2010 Enquiries should be addressed to: Andrew Heyward Australian Institute of Marine Science UWA Oceans Institute (M096) 35 Stirling Hwy Crawley, WA 6009 [email protected] © Copyright . PTTEP Australasia (Ashmore Cartier) Pty Ltd All rights are reserved and no part of this document may be reproduced, stored or copied in any form or by any means whatsoever except with the prior written permission of PTTEP Australasia (Ashmore Cartier) Pty Ltd DISCLAIMER While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this document are factually correct, AIMS does not make any representation or give any warranty regarding the accuracy, completeness, currency or suitability for any particular purpose of the information or statements contained in this document. To the extent permitted by law AIMS shall not be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of this document. Cover Photo : Ashmore Reef – shallow reef crest community on the central northern site A8 in April 2010. ii Benthic surveys at Ashmore, Cartier and Seringapatam Reefs Heyward et al.