Visitor Evaluation Toolbox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July - October 2016 I N This Issue on the Cover Notes from the Director’S Desk

July - October 2016 I N THIS ISSUE On the Cover Notes from the Director’s Desk. .......3 Cali the Hoffman’s Two-toed Sloth. ....4 Once the weather is consistently nice and warm, Cali moves to Say hello to Chuck the Swift Fox .......5 his outdoor enclosure that he AI duPont Hospital Goes Wild! . .....6 shares with a toucan and box Pythons, Gecko’s, and Skinks, Oh My! 7 turtle. Can’t find him? Check on Event Photo Montage ...........8&9 top of the brick wall at the back of Conservation Corner . ............. 10 the exhibit, in the hammock, or even July, Aug., Sept., Oct. Calendars. 11&12 in the wooden nest box on top of his wall. Sloths blend in well with the Red Panda Pilgrimage . .13 great outdoors so it may take a minute BZAAZK Happenings . ...........14 to find him. Society Executive Director’s Letter. ..15 Delaware Zoological Society Board of Directors 16 NJ Color.qxp_NJ–16 ZooAd 6/10/16 1:27 PM Page 13 Mike Allen Kevin Brandt Amy Colbourn, Vice President Diana DeBenedictis Greg Ellis Joan Goloskov Larry Gehrke Linda Gray Robert Grove, Treasurer Amy Hughes Carla Jarosz Wednesday Evening, July 13 John Malik Megan McGlinchey, President Thursday Evening, August 11 William Montgomery 6 PM to 8 PM Susan Moran, Secretary Special evening zoo hours hosted by Gene Peacock 93.7 WSTW FM. Meet radio personalities and Arlene Reppa enjoy learning stations, games and live animals. Matthew Ritter Richard Rothwell Birds presented by Animal Behavior & Daniel Scholl Conservation Connections. $1 Admission for everyone (BZ members are free!) EDITORS Des IGN/PRINTING $1 Hot Dogs, Pretzels and soft drinks, too! Jennifer Lynch** Professional Free Parking. -

2018 Annual Report Inside Front Cover Delaware State Parks 2018 Annual Report

DELAWARE STATE PARKS 2018 Annual Report Inside front cover Delaware State Parks 2018 Annual Report Voted America’s Best Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control Division of Parks & Recreation Blank page TABLE OF CONTENTS What Who Things How We Info By We Are We Are We Do Pay For It Park 5 Our Parks and 7 Our People Put 16 Preserving, 22 Funding the 33 Alapocas Run Preserves Us on Top in Supporting, Parks FY18 Teaching 35 Auburn Valley More Than 24 Investments in Parks 11 Volunteers 17 Programming Our Parks 37 Bellevue and by the Fox Point 6 Accessible to 13 Friends of Numbers 26 Partnerships All Delaware State 40 Brandywine Parks 18 Protect and 29 Small Creek Serve Businesses 14 Advisory 42 Cape Henlopen Councils 19 We Provided 30 Management Grants Challenges 45 Delaware Seashore and Indian River Marina 49 Fenwick Island and Holts Landing 51 First State Heritage Park 53 Fort Delaware, Fort DuPont, and Port Penn Interpretive Center 55 Killens Pond 57 Lums Pond 59 Trap Pond 62 White Clay Creek 65 Wilmington State Parks and Brandywine Zoo TIMELINE Wilmington State Parks/Brandywine Zoo The Division took over the management of the Brandywine 1998 ANNIVERSARIES Zoo and three parks in the City of Wilmington: Brandywine Park, Rockford Park and Alapocas Woods. 20 Auburn Valley State Park Brandywine Creek State Park YEARS 2008 Alapocas Run State Park AGO Tom and Ruth Marshall donated Bellevue State Park Auburn Heights to the Fox Point State Park Division, completing the 10 Auburn Heights Preserve. YEARS Shortly after, the remediation and AGO development of the former Fort Delaware State Park NVF property began. -

In This Issue

Winter 2012 Creative Solutions US Postal Tiger Stamp ZOOpendous Drawings of Zhanna Calendar of Events In This Issue IN THIS ISSUE On the Cover Conservation Corner . .3 Our llama (Llama glama) George Creative Solutions . 4,5 is a twenty year old male in our ZOOCamp . 6 herd. When he was fifteen, keepers EdZOOcation Programs . 7 noticed that he was having difficulty Ask the ZOO and meet BeeZee . 8 . Kid’s Corner . 9 breathing George was diagnosed Volunteers make our world . .10 with asthma. We also found out that Zoo Calendar . .12 horses can develop this as well and we were able to use an equine nebulizer to administer his medicine. He receives Delaware Zoological Society this treatment twice a day and has done Board of Directors very well. Michael Allen Raymond E. Bivens Amy Colbourn, Vice President Greg Ellis Larry Gehrke Linda Gray September 28th, Brandywine Zoo visitors, staff and local staff of Dana Griffin the U. S. Postal Service celebrated the unveiling of the new Save Robert Grove, Treasurer Vanishing Species Amur Tiger stamp. Deborah Grubbe Suzi Harris Net proceeds from the sales of John S. Malik the Save Vanishing Species Megan McGlinchey, President semipostal stamp will be transferred Ron Mercer to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Susan W. Moran, Secretary to support the Multinational Species Richard Rothwell Conservation Funds. The funds U.will be S.divided Postal among the AfricanService to Help SaveElephant Conservation Vanishing fund, Asian Species EDItoRS DESIGN/PRINTING Elephant Conservation fund, Great Nancy M. Falasco* Professional Ape Conservation Fund, Rhinoceros Duplicating, Inc. Jill Karlson and Tiger Conservation AssIst. -

In This Issue in THIS ISSUE on the Cover Notes from the Director’S Desk

May-August 2015 Notes from the Director’s Desk Safety First Delaware Zoological Society Top Four Questions about Camp Kid’s Corner Family Program Calendar Earth Day with Junior Explorers National Zoo Keeper Week In This Issue IN THIS ISSUE On the Cover Notes from the Director’s Desk . 3 This spring the monkeys are back! For the Safety First . .3 first time since the Exotic Animal Building Delaware Zoological Society. .4 was destroyed by a tree, you can see monkeys Tamarin Building Construction . 4 at the Brandywine Zoo. Our new Tamarin Top Four Questions about Camp. .5 building is located inside the zoo, across from the tiger exhibit. The Golden Lion Tamarins Kid’s Corner - Golden Lion Tamarin . .6 and Goeldi’s Monkeys have moved into their New ADOPT Program. .7 new home. Come see our monkeys enjoying Photo Spread . 8-9 their new experience of being outside. BZAAZK Updates . .10 Family Program Calendar. 11-12 Earth Day with Junior Explorers . .13 National Zoo Keeper Week . .15 Giving Tree Thank You. .16 Delaware Zoological Society Board of Directors Mike Allen Amy Colbourn, Vice President Diana DeBenedictis Greg Ellis Joan Goloskov Linda Gray Robert Grove, Treasurer Carla Jarosz In March, we welcomed Mini Melts as the Official Beaded John Malik Ice Cream of the Brandywine Zoo. The flavors of Mini Melts Megan McGlinchey, President available are Cookies & Cream, Banana Split, Cotton Candy, William Montgomery and Rainbow Ice. You can stop by the Concession Stand Susan Moran, Secretary to purchase some or visit the vending machines near the Gene Peacock Concession Stand and the Zootique. -

1 Updated April 2017

2017 DELAWARE DATA BOOK Updated April 2017 s s 1 2017 DELAWARE DATA BOOK DELAWARE’S ECONOMY 3 FIRST STATE TAXES AND INCENTIVES 8 DELAWARE DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT 26 LIVING IN DELAWARE 27 DELAWARE EDUCATION 49 DELAWARE KEEPS YOU MOVING 59 DELAWARE RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT 71 DELAWARE’S WORKFORCE 81 THE DELAWARE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OFFICE 85 ONE STOP BUSINESS REGISTRATION 93 SMALL BUSINESS & TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT CENTER (SBTDC) 94 SITE SELECTION EXPERTISE 97 UTILITIES AND RESOURCES 109 2 2017 DELAWARE DATA BOOK s 3 2017 DELAWARE DATA BOOK Delaware has the strongest state economy in the region. With lower than average unemployment, a fair and equitable tax system, and a well‐trained workforce, the state’s economic climate has shown dramatic improvement since the early 1980’s, partially in response to stable fiscal policies, careful debt management, conservative spending programs, and personal income tax reductions. The Delaware Economic Development Office was created in 1981 with a mission to be responsible for attracting new investors and business to the State, promoting the expansion of existing industry, assisting small and minority‐owned businesses, promoting and developing tourism and creating new and improved employment opportunities for all citizens of the State. This section describes Delaware’s strides towards continuous economic improvement and includes the following: Unemployment Statistics State Government Financial Position Delaware’s Financial Overview Excellent Debt Management 4 2017 DELAWARE DATA BOOK Unemployment Statistics Delaware remains an above average performer in comparison to the national economy; Delaware’s economy continues to exhibit resiliency and remains highly competitive. Delaware’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate as of December 2016 was 4.3%, which was 0.4 lower than the national average of 4.7%. -

In This Issue Spring 2013

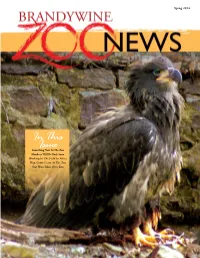

Sprng 2014 Something New At The Zoo Monkeys Will Be Back Soon Working In The Field In Africa Play, Grow, Learn At The Zoo Star Wars Takes Over Zoo In This Issue Spring 2013 IN THIS ISSUE On the Cover Partying With A Purpose . 3 Our cover features someone new here Something New At The Zoo . 4 at the zoo. She’s a juvenile Bald Eagle Monkeys Will Be Back Soon . 5 (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) who came to Meet Donna Evernham . .5 us from a rehabilitation facility. She was Enrichment and Training . 6-7 permanently injured when she was blown Our Commitment To Conservation .8 out of her nest in western Pennsylvania in a violent storm. As a result, she cannot Kid’s Corner . 9 Something New At The Zoo Monkeys Will Be Back Soon Working In The Field In Africa fly and is unable to survive on her own in Play, Grow, Learn At The Zoo Working In The Field In Africa . 10-11 Star Waqars Takes Over Zoo the wild. We are pleased to be able to pro- Family Programs . 12-13 In This Play, Grow, Learn At The Zoo . 14 vide her a new home at the Brandywine Zoo Issue where she can receive excellent care from our Star Wars Takes Over Zoo . .15 animal keepers. Our members and visitors will New Year & Volunteer Program 16-17 have the unique opportunity to watch her grow AAZK . .18 into adulthood and take on the distinctive white Reciprocal Zoos & Aquariums . 19 plumage on her head and tail that will identify her as our national symbol. -

November 2018 - February 2019 in This Issue O N the Cover Zoo Director’S Letter

November 2018 - February 2019 IN THIS ISSUE O n the Cover Zoo Director’s Letter. ................3 The Andean Condor is a South American Brew at the Zoo Thank yous ......4 & 5 bird with a wide wingspan (up to 10 ft) and Volunteers & Interns . ................6 long lifespan of 70 years. The male has a BZAAZK Happenings ...............7 wattle on the neck and a red comb on the Boo at the Zoo ..................8 & 9 crown of his head. Unlike most birds, the male Great gifts in the gift shop. .......... 10 is larger than the female. Our Condor pair, Gryphus and Chavin, were hatched in 1979 Executive Director’s Letter .......... 11 at the Bronx Zoo and in 1986 at the LA Zoo, Open House at the Zoo ............ 12 respectively. Board of Directors Andean condors are a vital part of the ecosystem as they help remove dead and decaying animals Arlene Reppa, President and in turn, are reducing disease spread. Photo by: John Otley Diana DeBenedictis, Vice President Kevin Brandt, Treasurer Vickie Innes, Secretary Donna Fierro Linda M. Gray Amy Hughes John S. Malik Megan McGlinchey Michael Milligan William S. Montgomery Matthew Ritter Richard Rothwell Daniel F. Scholl Michael T. Allen, Executive Director Brint Spencer, Zoo Director Support Staff Melanie Flynn, Visitor Services Manager Jennifer Lynch, Marketing & Special Events Manager Breakfast with Santa EDITORS WRITERS December 8 & 9 • 9:00-10:00AM Mike Allen** Mike Allen** Celebrate the holidays by enjoying a pancake, egg, Jennifer Lynch** Emily Culkin** Melanie Flynn** & sausage breakfast with Santa! Share your holiday wishes, bring your PHOTO Katlyn Muse* camera to take photos with Santa and some animal friends, CONTRIBUTIONS Emily Culkin** Danielle Leverage* and enjoy a few up-close animal encounters Jennifer Lynch** Jennifer Lynch** all before the zoo opens. -

2019 Annual Report on Conservation and Science

Annual Report on Conservation and Science INTRODUCTION 2 2019 Annual Report on Conservation and Science The Association of Zoos and Aquariums and its member facilities envision a world where, as a result of their work, all people respect, value and conserve wildlife and wild places. The 2019 Annual Report on Conservation and Science (ARCS) celebrates the conservation efforts, education programs, green (sustainable) business practices, and research projects of AZA-accredited zoos and aquariums and certified related facilities. Content in ARCS reflects submissions made to annual surveys available through AZA’s website. Each survey topic has been carefully defined to maximize consistency of reporting throughout the AZA community. AZA’s Field Conservation Committee and Research and Technology Committee review all of the relevant submissions by members to promote even greater consistency. Field conservation focuses on efforts having a direct impact on animals and habitats in the wild. Education programming includes those with specific goals and delivery methods, defined content and a clear primary discipline and target audience. Mission-focused research projects involve application of the scientific method, are hypothesis (or question)-driven, involve systematic data collection and analysis of those data and draw conclusions from the research process. Green business practices focus on the annual documentation and usage of key resources: energy, fuel for transportation, waste and water – as well as identification of specific green practices being implemented. AZA is grateful to each member that responded to these surveys. The response rate for each 2019 survey was as follows: » field conservation – 92% » education programming – 58% » green business practices – 66% » mission-focused research – 72% While the 2019 ARCS focuses on individual activities undertaken that year, download the 2019 Highlights (available at: aza.org/annual-report-on-conservation-and-science) to learn more about what the AZA community accomplished together. -

Zoo Brochure 1/28/20 3:38 PM Page 1

Sponsorship 2018.qxp_Zoo Brochure 1/28/20 3:38 PM Page 1 Sponsorship Opportunities at the 1001 North Park Drive • Wilmington,DE 19802 302-571-7788 • brandywinezoo.org The Brandywine Zoo is managed by the Delaware Division of Parks and Recreation with the support of the Delaware Zoological Society. Sponsorship 2018.qxp_Zoo Brochure 1/28/20 3:38 PM Page 2 Sponsorship Opportunities Sponsorship Opportunities at the Brandywine Zoo Thank you for considering a sponsorship at the Brandywine Zoo. Your support helps us continue to sustain and advance our Education and Conservation Programs, as well as maintain the unique, family-oriented environment that makes the Zoo such a special place. The Brandywine Zoo opened its doors in 1905—now, more than 100 years later, the Zoo continues to provide fun, entertainment and learning to adults and children alike throughout the region. Each year, through special events, innovative programs and on-going popular activities, the Brandywine Zoo targets adults and children of every age, stimulating excitement and interest in our Zoo and the animals who live there, while creating awareness of the endangered wildlife in Delaware and around the world. In addition to the entertainment component, our over-arching emphasis continues to be on maintaining and strengthening our exceptional Education and Conservation Programs. The Zoo offers a variety of sponsorship opportunities: from special events and programs to education projects, conservation initiatives and exhibits. Many sponsorships can be customized to meet a company’s specific needs. All offer strong visibility for the sponsor as well as employee benefits such as Zoo passes, discounts, and more. -

Chapter 5 INTRINSIC QUALITIES

Chapter 5 INTRINSIC QUALITIES The Brandywine Valley Scenic Byway possesses significant intrinsic qualities as outlined in the national Scenic Byway program and meets state and federal program requirements for Byway designation. It is these intrinsic qualities that set it apart from other roads in the state, the region and the nation. These special qualities exist today largely due to the preservation legacy of the du Ponts together with earlier philanthropic industrialists like the Bancrofts and Canbys. Recognizing the value of these resources, many organizations and individuals have worked over the years to provide outstanding stewardship of these intrinsic qualities. As a result, the Brandywine Valley today is worthy of state and national recognition as a Scenic Byway. Resources associated with each of the Byway’s intrinsic qualities are identified below in the text and on two accompanying maps at the end of the chapter. The map entitled Brandywine Valley Byway Features identifies historic sites, historic districts, and public parks. A full listing of the historic sites indicated on the map is included as Appendix C to this Plan. The Brandywine Valley Byway Resources map shows protected lands within the corridor as well as high-quality views. The special character of the Brandywine Valley Scenic Byway contrasts sharply with today’s modern interstate highways. The cross-section of communities, layers of history, scenic views and historic, cultural, and landscape resources all create a unique travel experience like none other in the nation. The Byway conforms to the rolling topography of the Piedmont and passes through quaint historic villages, heavily forested areas, pastoral agricultural fields, and bustling downtown Wilmington. -

Brandywine Zoo Animal Handling Manual 1.0 USDA Guidelines 2.0 Animal Handling Classifications, Training Requirements and Respons

Brandywine Zoo Animal Handling Manual Updated: 4/21/2018 1.0 USDA Guidelines ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 3.0 Prevention of Animal Bites, Injuries, and Escapes ..................................................................................................... 2 4.0 Taxon Specific Protocols ...................................................................................................................................................... 2 5.0 General Guidelines for Program Animals ...................................................................................................................... 3 6.0 Frequency of use for program animals .......................................................................................................................... 4 7.0 General guidelines for packing animals ........................................................................................................................ 4 8.0 Outdoor Seasonal Considerations ................................................................................................................................... 5 9.0 Using Enclosure Cards .......................................................................................................................................................... 6 10.0 Animal or Person Emergencies ........................................................................................................................................ -

New Castle County LIFESTYLE GUIDE 2014 Personalized Service & Collaborative Teamwork We’Re Here for You

New Castle County LIFESTYLE GUIDE 2014 Personalized service & collaborative teamwork We’re Here for You. Your business is our business. Personalized service and collaborative teamwork form the core of our commitment to client satisfaction. We provide comprehensive solutions focused on your business strategies. Allow us to turn your next real estate challenge into a success. Commercial and Residential Real Estate Brokerage Commercial Construction | Property Management | Maintenance 10 Corporate Circle, Suite 100 New Castle, DE 302.322.9500 18335 Coastal Highway Lewes, DE 302.827.4940 Real Estate. Construction. Excellence. www.emoryhill.com County Executive Welcome Message n behalf of our 540,000 in Greater Wilmington. In the ever-growing fi eld residents, it is with great Additionally, there is also of quality health care, pride that I welcome you an eclectic mix of college New Castle County is Oto New Castle County, and residential life in the home to Christiana Care the “First County in the First State.” O u r city of Newark. HealthH System, a major County is located in the northern-most For those who want teachingt hospital and one section of Delaware, just west of the to experience a little ofo the country’s largest, Delaware River. bit more, just a short state-of-the-arts health care Th ere is much natural beauty drive away is Rehoboth providers.p to experience and enjoy in New Beach, Del., and other Solid public safety Castle County. Th e meadows and relaxing shore points. New Castle eff orts provide for a secure rolling hills of Chateau Country, the County is also the midpoint between environment in which business and pristine Delaware River shore and the New York City and Washington, D.C., commerce can thrive.