Weed-Insect Pollinator Networks As Bio-Indicators of Ecological Sustainability in Agriculture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smith, Darrell (2014) a Values-Based Wood-Fuel Landscape Evaluation: Building a Fuzzy Logic Framework to Integrate Socio-Cultural, Ecological, and Economic Value

Smith, Darrell (2014) A values-based wood-fuel landscape evaluation: building a fuzzy logic framework to integrate socio-cultural, ecological, and economic value. Doctoral thesis, Lancaster University. Downloaded from: http://insight.cumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/3191/ Usage of any items from the University of Cumbria’s institutional repository ‘Insight’ must conform to the following fair usage guidelines. Any item and its associated metadata held in the University of Cumbria’s institutional repository Insight (unless stated otherwise on the metadata record) may be copied, displayed or performed, and stored in line with the JISC fair dealing guidelines (available here) for educational and not-for-profit activities provided that • the authors, title and full bibliographic details of the item are cited clearly when any part of the work is referred to verbally or in the written form • a hyperlink/URL to the original Insight record of that item is included in any citations of the work • the content is not changed in any way • all files required for usage of the item are kept together with the main item file. You may not • sell any part of an item • refer to any part of an item without citation • amend any item or contextualise it in a way that will impugn the creator’s reputation • remove or alter the copyright statement on an item. The full policy can be found here. Alternatively contact the University of Cumbria Repository Editor by emailing [email protected]. A values-based wood-fuel landscape evaluation: building a fuzzy logic framework to integrate socio- cultural, ecological, and economic value by Darrell Jon Smith BSc (Hons.) Lancaster University 2014 This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

BRINSLEY HEADSTOCKS Heritage & Nature Reserve. BUTTERFLIES

BRINSLEY HEADSTOCKS Heritage & Nature Reserve. BUTTERFLIES and MOTHS 2016 BUTTERFLIES The mix of unimproved meadow, woodland and hedgerows provide an ideal habitat for a number of butterfly species. The total number of species recorded to date is 21, a very respectable total for a site the size of the Headstocks Nature Reserve. The number of species recorded in 2016 was 14 ( down from 18 in 2015 ). Recording was very difficult in 2016, as major path improvements on site from May until July made access difficult due to the heavy machinery used. The cold, wet spring also had an impact on early-flying species and once again the early cutting of the hay in the meadows curtailed the breeding success of the grassland butterflies. SMALL SKIPPER Thymelicus sylvestris The only record for the year was of two insects of this species seen on July 24th 2016. This species is normally recorded regularly in its flight period, with a maximum of eight recorded in 2015. ESSEX SKIPPER Thymelicus lineola Not recorded in 2016. The first site record for this species was of a single on August 12th 2015. There had been a few sightings of “possibles” in the preceding days, but the identity was confirmed by netting and close examination in an inspection jar. LARGE SKIPPER Ochlodes venatus A sin the last two years, there was only a single record of this species in 2016, when one was seen on July 5th. Normally present in both the long meadow and the headstocks meadow, although not as numerous as small skipper. BRIMSTONE Gonepteryx rhamni There were two records of this species in 2016, both in April and May ( as in 2015 ). -

Recerca I Territori V12 B (002)(1).Pdf

Butterfly and moths in l’Empordà and their response to global change Recerca i territori Volume 12 NUMBER 12 / SEPTEMBER 2020 Edition Graphic design Càtedra d’Ecosistemes Litorals Mediterranis Mostra Comunicació Parc Natural del Montgrí, les Illes Medes i el Baix Ter Museu de la Mediterrània Printing Gràfiques Agustí Coordinadors of the volume Constantí Stefanescu, Tristan Lafranchis ISSN: 2013-5939 Dipòsit legal: GI 896-2020 “Recerca i Territori” Collection Coordinator Printed on recycled paper Cyclus print Xavier Quintana With the support of: Summary Foreword ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Xavier Quintana Butterflies of the Montgrí-Baix Ter region ................................................................................................................. 11 Tristan Lafranchis Moths of the Montgrí-Baix Ter region ............................................................................................................................31 Tristan Lafranchis The dispersion of Lepidoptera in the Montgrí-Baix Ter region ...........................................................51 Tristan Lafranchis Three decades of butterfly monitoring at El Cortalet ...................................................................................69 (Aiguamolls de l’Empordà Natural Park) Constantí Stefanescu Effects of abandonment and restoration in Mediterranean meadows .......................................87 -

The Radiation of Satyrini Butterflies (Nymphalidae: Satyrinae): A

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2011, 161, 64–87. With 8 figures The radiation of Satyrini butterflies (Nymphalidae: Satyrinae): a challenge for phylogenetic methods CARLOS PEÑA1,2*, SÖREN NYLIN1 and NIKLAS WAHLBERG1,3 1Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 2Museo de Historia Natural, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Av. Arenales 1256, Apartado 14-0434, Lima-14, Peru 3Laboratory of Genetics, Department of Biology, University of Turku, 20014 Turku, Finland Received 24 February 2009; accepted for publication 1 September 2009 We have inferred the most comprehensive phylogenetic hypothesis to date of butterflies in the tribe Satyrini. In order to obtain a hypothesis of relationships, we used maximum parsimony and model-based methods with 4435 bp of DNA sequences from mitochondrial and nuclear genes for 179 taxa (130 genera and eight out-groups). We estimated dates of origin and diversification for major clades, and performed a biogeographic analysis using a dispersal–vicariance framework, in order to infer a scenario of the biogeographical history of the group. We found long-branch taxa that affected the accuracy of all three methods. Moreover, different methods produced incongruent phylogenies. We found that Satyrini appeared around 42 Mya in either the Neotropical or the Eastern Palaearctic, Oriental, and/or Indo-Australian regions, and underwent a quick radiation between 32 and 24 Mya, during which time most of its component subtribes originated. Several factors might have been important for the diversification of Satyrini: the ability to feed on grasses; early habitat shift into open, non-forest habitats; and geographic bridges, which permitted dispersal over marine barriers, enabling the geographic expansions of ancestors to new environ- ments that provided opportunities for geographic differentiation, and diversification. -

Additions, Deletions and Corrections to An

Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) ADDITIONS, DELETIONS AND CORRECTIONS TO AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE IRISH BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA) WITH A CONCISE CHECKLIST OF IRISH SPECIES AND ELACHISTA BIATOMELLA (STAINTON, 1848) NEW TO IRELAND K. G. M. Bond1 and J. P. O’Connor2 1Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology, School of BEES, University College Cork, Distillery Fields, North Mall, Cork, Ireland. e-mail: <[email protected]> 2Emeritus Entomologist, National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. Abstract Additions, deletions and corrections are made to the Irish checklist of butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera). Elachista biatomella (Stainton, 1848) is added to the Irish list. The total number of confirmed Irish species of Lepidoptera now stands at 1480. Key words: Lepidoptera, additions, deletions, corrections, Irish list, Elachista biatomella Introduction Bond, Nash and O’Connor (2006) provided a checklist of the Irish Lepidoptera. Since its publication, many new discoveries have been made and are reported here. In addition, several deletions have been made. A concise and updated checklist is provided. The following abbreviations are used in the text: BM(NH) – The Natural History Museum, London; NMINH – National Museum of Ireland, Natural History, Dublin. The total number of confirmed Irish species now stands at 1480, an addition of 68 since Bond et al. (2006). Taxonomic arrangement As a result of recent systematic research, it has been necessary to replace the arrangement familiar to British and Irish Lepidopterists by the Fauna Europaea [FE] system used by Karsholt 60 Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) and Razowski, which is widely used in continental Europe. -

Botolph's Bridge, Hythe Redoubt, Hythe Ranges West And

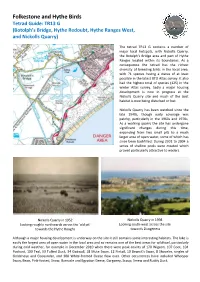

Folkestone and Hythe Birds Tetrad Guide: TR13 G (Botolph’s Bridge, Hythe Redoubt, Hythe Ranges West, and Nickolls Quarry) The tetrad TR13 G contains a number of major local hotspots, with Nickolls Quarry, the Botolph’s Bridge area and part of Hythe Ranges located within its boundaries. As a consequence the tetrad has the richest diversity of breeding birds in the local area, with 71 species having a status of at least possible in the latest BTO Atlas survey. It also had the highest total of species (125) in the winter Atlas survey. Sadly a major housing development is now in progress at the Nickolls Quarry site and much of the best habitat is now being disturbed or lost. Nickolls Quarry has been watched since the late 1940s, though early coverage was patchy, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s. As a working quarry the site has undergone significant changes during this time, expanding from two small pits to a much larger area of open water, some of which has since been backfilled. During 2001 to 2004 a series of shallow pools were created which proved particularly attractive to waders. Nickolls Quarry in 1952 Nickolls Quarry in 1998 Looking roughly northwards across the 'old pit' Looking south-west across the site towards the Hythe Roughs towards Dungeness Although a major housing development is underway on the site it still contains some interesting habitats. The lake is easily the largest area of open water in the local area and so remains one of the best areas for wildfowl, particularly during cold weather, for example in December 2010 when there were peak counts of 170 Wigeon, 107 Coot, 104 Pochard, 100 Teal, 53 Tufted Duck, 34 Gadwall, 18 Mute Swan, 12 Pintail, 10 Bewick’s Swan, 8 Shoveler, singles of Goldeneye and Goosander, and 300 White-fronted Geese flew over. -

Phylogenetic Relatedness of Erebia Medusa and E. Epipsodea (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) Confirmed

Eur. J. Entomol. 110(2): 379–382, 2013 http://www.eje.cz/pdfs/110/2/379 ISSN 1210-5759 (print), 1802-8829 (online) Phylogenetic relatedness of Erebia medusa and E. epipsodea (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) confirmed 1 2, 3 4 MARTINA ŠEMELÁKOVÁ , PETER PRISTAŠ and ĽUBOMÍR PANIGAJ 1 Institute of Biology and Ecology, Department of Cellular Biology, Faculty of Science, Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice, Moyzesova 11, 041 54 Košice, Slovakia; e-mail: [email protected] 2 Institute of Animal Physiology, Slovak Academy of Science, Soltesovej 4–6, 040 01 Košice, Slovakia 3 Department of Biology and Ecology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Matej Bel University, Tajovskeho 40, 841 04 Banská Bystrica, Slovakia 4 Institute of Biology and Ecology, Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice, Moyzesova 11, 041 54 Košice, Slovakia Key words. Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae, Erebia medusa, E. epipsodea, mtDNA, COI, ND1 Abstract. The extensive genus Erebia is divided into several groups of species according to phylogenetic relatedness. The species Erebia medusa was assigned to the medusa group and E. epipsodea to the alberganus group. A detailed study of the morphology of their copulatory organs indicated that these species are closely related and based on this E. epipsodea was transferred to the medusa group. Phylogenetic analyses of the gene sequences of mitochondrial cytochrome C oxidase subunit I (COI) and mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 (ND1) confirm that E. medusa and E. epipsodea are closely related. A possible scenario is that the North American species, E. episodea, evolved after exclusion/isolation from E. medusa, whose current centre of distribution is in Europe. -

Nota Lepidopterologica

©Societas Europaea Lepidopterologica; download unter http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ und www.zobodat.at Nota lepid. 23 (2): 1 19-140; 01.VIL2000 ISSN 0342-7536 Comparative data on the adult biology, ecology and behaviour of species belonging to the genera Hipparchia, Chazara and Kanetisa in central Spain (Nymphalidae: Satyrinae) Enrique Garcia-Barros Department of Biology (Zoology), Universidad Autönoma de Madrid, E-28049 Madrid, Spain, e-mail: [email protected] Summary. The potential longevity, fecundity, mating frequencies, behaviour, and sea- sonal reproductive biology were studied in several satyrine butterflies belonging to the genera Hipparchia, Chazara and Kanetisa, in an area located in central Spain. All the species studied appear to be potentially long-lived, and a relatively long period of pre- oviposition is shown to occur in C. briseis and K. circe. Potential fecundity varies between 250 and 800 eggs depending on the species (with maxima exceeding 1300 eggs in K. circe). The results are discussed in terms of the possible ecological relationships between adult ecological traits and the species abundance, and the possibility of a marked geographic variation between species, that might be of interest in relation to specific management and conservation. Zusammenfassung. Für mehrere Vertreter der Gattungen Hipparchia, Chazara und Kanetisa (Satyrinae) wurden in einem Gebiet in Zentralspanien potentielle Lebensdauer, potentielle Fekundität, Paarungshäufigkeiten im Freiland und saisonaler Verlauf der Reproduktionstätigkeit untersucht. Alle untersuchten Arten sind potentiell langlebig, eine relativ lange Präovipositionsperiode tritt bei C. briseis und K circe auf. Die potentielle Fekundität variiert je nach Art zwischen 250 und 800 Eiern (mit einem Maximum von über 1300 Eiern bei K circe). -

The Lepidoptera of Formby

THE RAVEN ENTOMOLOGICAL — AND — NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY FOUNDED 1946 THE LEPIDOPTERA OF FORMBY Price: TWO SHILLINGS & SIXPENCE THE RAVEN ENTOMOLOGICAL AND NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY FOUNDED 1946 THE LEPIDOPTERA OF FORMBY — B Y — M. J. LEECH H. N. MICHAELIS With a short biographical note on the late G. de C. Fraser by C. de C. Whiteley For us the wide open spaces, the mountams and valleys, the old walls and the hedges and ditches, wherein lie adventure and interest for to-day, to-morrow, and a lifetime. n Printed by T. B unci-e & Co. L td., Arbroath. GKRALI) i)E C. FRASER rOHEWORl) FOREWORD BY AI,LAN BRJNDLK TT was in August, 1939, that T first liad the pleasure of meeting the Frasers. Together with a small party of entomologists from N.E. I.ancashire. invited to eollect at light near the shore at Formby, I experienced the somewhat overwhelming enthrisiasm and hospitality extended to all at “ Warren Mount” . Fed, feted, and equipped, we were taken by cars to the shore, sheets were laid down in front of the headlights, and a memorable night ensued. The night was dark and warm, the moths arrived in great numbers and, true to the Fraser tradition, work did not cease until a few minutes before the last train left Formby, when a hurried dash to the station deposited a happy party of entomologists on the first stage of the journey home. The next meeting was long delayed. The following week-end saw the black-out in force, and it was not until 1946 that T found the Frasens, still enthusiastic, establishing the Eaven Society. -

A Guide to the Management and Restoration of Coastal Vegetated Shingle

A Guide to the Management and Restoration of Coastal Vegetated Shingle By Dr Pat Doody and Dr Roland Randall May 2003 Contract No. MAR 05-03-002 English Nature A Guide to the Management and Restoration of Coastal Vegetated Shingle Contractors: Dr J. Pat Doody National Coastal Consultants 5 Green Lane BRAMPTON Huntingdon Cambs., PE28 4RE, UK Tel: 01480 392706 E-mail: [email protected] and Dr Roland E. Randall Monach Farm Ecological Surveys St Francis Toft HILTON Huntingdon Cambs, Tel: 01223 338949 E-mail: [email protected] Nominated Officer: Tim Collins EN Headquarters Peterborough Frontispiece: Dungeness - shingle extraction on the downdrift (eastern side) of the ness. The material is taken by lorries to nourish the beach to the west. Longshore drift moves it eastwards again providing protection for the nuclear power stations present on this tip of England - a never ending cycle of coastal protection? Page ii Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank all the people who contributed to this report, most notably the local officers and site managers who gave freely of their time, including Mike Edgington, Simon Dunsford, Barry Yates, Rob Carver, Julie Hatcher, Brian Banks and Grant Lohoar. Thanks also to English Nature staff at Peterborough Tim Collins, Sue Reid, Sue Watt and also to Pippa Sneddon, Ian Agnew, Robin Fuller and John Packham for past and present involvement. A special thanks to Andrew Leader for sorting out the conflicts between PCs and Macs and for other IT help. All photographs are copyright of Dr J.P Doody or Dr R.E. Randall. -

Scottish Macro-Moth List, 2015

Notes on the Scottish Macro-moth List, 2015 This list aims to include every species of macro-moth reliably recorded in Scotland, with an assessment of its Scottish status, as guidance for observers contributing to the National Moth Recording Scheme (NMRS). It updates and amends the previous lists of 2009, 2011, 2012 & 2014. The requirement for inclusion on this checklist is a minimum of one record that is beyond reasonable doubt. Plausible but unproven species are relegated to an appendix, awaiting confirmation or further records. Unlikely species and known errors are omitted altogether, even if published records exist. Note that inclusion in the Scottish Invertebrate Records Index (SIRI) does not imply credibility. At one time or another, virtually every macro-moth on the British list has been reported from Scotland. Many of these claims are almost certainly misidentifications or other errors, including name confusion. However, because the County Moth Recorder (CMR) has the final say, dubious Scottish records for some unlikely species appear in the NMRS dataset. A modern complication involves the unwitting transportation of moths inside the traps of visiting lepidopterists. Then on the first night of their stay they record a species never seen before or afterwards by the local observers. Various such instances are known or suspected, including three for my own vice-county of Banffshire. Surprising species found in visitors’ traps the first time they are used here should always be regarded with caution. Clerical slips – the wrong scientific name scribbled in a notebook – have long caused confusion. An even greater modern problem involves errors when computerising the data. -

Insecta: Lepidoptera) SHILAP Revista De Lepidopterología, Vol

SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología ISSN: 0300-5267 [email protected] Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología España Corley, M. F. V.; Rosete, J.; Gonçalves, A. R.; Nunes, J.; Pires, P.; Marabuto, E. New and interesting Portuguese Lepidoptera records from 2015 (Insecta: Lepidoptera) SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología, vol. 44, núm. 176, diciembre, 2016, pp. 615-643 Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45549852010 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative SHILAP Revta. lepid., 44 (176) diciembre 2016: 615-643 eISSN: 2340-4078 ISSN: 0300-5267 New and interesting Portuguese Lepidoptera records from 2015 (Insecta: Lepidoptera) M. F. V. Corley, J. Rosete, A. R. Gonçalves, J. Nunes, P. Pires & E. Marabuto Abstract 39 species are added to the Portuguese Lepidoptera fauna and one species deleted, mainly as a result of fieldwork undertaken by the authors and others in 2015. In addition, second and third records for the country, new province records and new food-plant data for a number of species are included. A summary of recent papers affecting the Portuguese fauna is included. KEY WORDS: Insecta, Lepidoptera, distribution, Portugal. Novos e interessantes registos portugueses de Lepidoptera em 2015 (Insecta: Lepidoptera) Resumo Como resultado do trabalho de campo desenvolvido pelos autores e outros, principalmente no ano de 2015, são adicionadas 39 espécies de Lepidoptera à fauna de Portugal e uma é retirada.