Timor Leste: an Evaluation of WFP's Portfolio (2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It's Better to Know! Learn the Signs. Act Early. Photo Novella

It’s Better to Know! Learn the Signs. Act Early. Learning About Developmental Milestones All of us want our children to be happy and healthy. We want what is best for them. This story is about my family as we learn that “It’s Better To Know” about developmental milestones. Developmental milestones are things most children can do by a certain age. Children reach milestones in how they play, learn, speak, and act. Milestones offer important clues about a child’s development. The developmental milestones you will learn about in this fotonovela will give you a general idea of what to expect as your child grows. Not reaching these milestones, or reaching them much later than other children, could be a sign of a developmental delay. Trust your instincts. If you have concerns about your child’s development, the best thing to do is talk with your doctor. It’s Better To Know! was produced by the Organization for Autism Research with funding provided by the Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/actearly iii He’s fine. He’s more interested in Hi Carlitos! his cow! C-a-r-l-i-t-o-s. He doesn’t always look at us when we call his name. I wonder why. Have you talked to How’s my baby boy the doctor about doing? that? He’s okay, mom, but he doesn’t always look up when No, why, should I? we call him. Remember the last time we took him for a well- baby check-up and 9-month developmental screening? I picked up this pamphlet in the waiting room. -

Download the Fall Commencement 2020 Program

FALL 2020 ACADEMIC REGALIA Though our ceremonies look different this year, regalia traditions are beloved, timeless and span decades — and pandemics. Our graduates have earned the right to don regalia and adornments for the rest of their lives that reflect the dedication they have shown to their field and the love they have for their alma mater. The custom of recognizing the accomplishments of scholars through distinctive dress, color and ceremony began in the Middle Ages and has been adopted by various academic institutions throughout the world. American academic regalia developed from the English traditions that originated at the University of Cambridge and the University of Oxford and has been in continuous use in this country since Colonial times. Institutions of higher learning in the United States have adopted a system for identifying different academic degrees by use of specific gowns, hoods and colors. The baccalaureate (bachelor’s) gown is identified by long pointed sleeves. The master’s gown has a very long sleeve, closed at the bottom, and the wearer’s arm is placed through an opening in the front of the sleeve. Master’s gowns also are distinguished by green panels down the front of the gown. Doctoral gowns are distinguished by velvet panels around the neck and down the front of the gown. Three horizontal velvet bars on each sleeve also may mark the doctorate. The colorful hoods worn by master’s and doctoral graduates represent the specific degree earned and the degree-granting institution. Hoods for UNT are distinguished by a kelly-green-and-white chevron lining. -

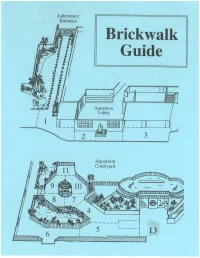

Brick Book 2015 with Guide.Pdf

MOTE MARINE LABORATORY AND AQUARIUM COMMEMORATIVE BRICKS NAME LOCATION ABATEMARCO, DANIELLA, JOEY, ANTHONY 8 ABBEY, PYGMY KILLER WHALE GMMC ABBOTT, COOPER FOLASA 7 ABBOTT, MUFFIE & STEVE 8 ABBY & EMMA 1 ABIGAIL, T.R.L. 3 ABKIN, HANNAH - 12/25/2014 2 ABRAHAM, ROLAND 1 ABUZA, DAVID CHAPIN 3 ABUZA, LEAH ELLEN 3 ABUZA, REBECCA ROSE 3 ASH, BILL AND FREDDIE 13 ACQUARO, DR. RONALD S AND BEVERLY 3 ADAM, ADDIE IN LOVING MEMORY OF 10 ADAM, REGAN, CHANDLER ET AL. 4 ADAMS, PETER & THELMA 3 ADAMS, ROBERT AND PAT 1 ADOMEIT, JASON CARL IN MEMORY OF 4 AHEARN, ATTICUS 8 AHMARI, DR. M. 2 AIKMAN, ELISE JOSHUA GRACE 7 AIKMAN, JIM 7 AKTION CLUB THANKS THE KIWANIS CLUBS 6 AKTION CLUB, 3 CHEERS FOR MOTE & KIWANIS 5 AKTION CLUB, HELPING AFTER JEAN,CHARLEY 5 AKTION CLUB, HERE TO HELP OTHERS 5 AKTION CLUB, HURRICANE 04 RELIEF 5 AKTION CLUB, SPECIAL NEEDS VOLUNTEERS 5 AKTION CLUB, WE ARE NUMBER ONE 5 ALAN AND DORIS WITH LOVE, 6 ALBURN, TOM & PATRICE BOEKE - THANKS GENIE 1 ALBERT, JANE AND JOHN 3 ALBIEZ, ROBERT AND PATRICIA 3 ALBION, TONYA 9 ALBRECHT, MARISSA 8 ALBRIGHT, DAVID AND HEATHER 3 ALBRIGHT, GEORGIANA - IN MEMORY OF 3 ALBRIGHT, JOHN AND THERESA 3 ALCORTA, CARLOS AND LIDIA 2 ALCORTA, CRISTINA AND CARLITOS 2 ALESSI,ANDREW GMMC MOTE MARINE LABORATORY AND AQUARIUM COMMEMORATIVE BRICKS NAME LOCATION ALEX, STEVIE 2 ALEXANDER, RICHARD GMMC ALEXANDER, SAKER IN MEMORY OF 2 ALEXANDER,DICK 2 ALEXANDER, DICK - VOLUNTEE PRESIDENT COURTYARD ALFANO, SUSAN OUR LOVE WILL LAST 8 ALLAN, LINDSAY AND JORDAN SHARK ALLEN FAMILY 2 ALLEN, CHRIS LEIGH 4 ALLEN, JIM AND ALICE 5 ALLEN, PAUL AND JACKIE 2 ALLIE, CELIA, CAMILLE & CHARLIE GMMC-INSIDE ALLIS, LOIS AND TOM 3 ALMAR CREW 3 ALTEMOSE, LAWRENCE J., IN LOVING MEMORY 7 ALTERISIO, SUSAN 2 ALTHANI, MR. -

ROCK 'DO: RESURGENCE of a RESILIENT SOUND in U.S., Fresh Spin Is Put on Format Globally, `No- Nonsense' Music Thrives a Billboard Staff Report

$5.95 (U.S.), $6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) ZOb£-L0906 VO H3V38 9N01 V it 3AV W13 047L£ A1N331J9 A1NOW 5811 9Zt Z 005Z£0 100 lllnlririnnrlllnlnllnlnrinrllrinlrrrllrrlrll ZL9 0818 tZ00W3bL£339L080611 906 1I9I0-£ OIE1V taA0ONX8t THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO, AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT r MARCH 6, 1999 ROCK 'DO: RESURGENCE OF A RESILIENT SOUND In U.S., Fresh Spin Is Put On Format Globally, `No- Nonsense' Music Thrives A Billboard staff report. with a host of newer acts being pulled A Billboard international staff Yoshida says. in their wake. report. As Yoshida and others look for NEW YORK -In a business in which Likewise, there is no one defining new rock -oriented talent, up -and- nothing breeds like success, "musical sound to be heard Often masquerading coming rock acts such as currently trends" can be born fast and fade among the pack, only as different sub-gen- unsigned three -piece Feed are set- faster. The powerful resurgence of the defining rock vibe res, no-nonsense rock ting the template for intelligent, rock bands in the U.S. market -a and a general feeling continues to thrive in powerful Japanese rock (Global phenomenon evident at retail and that it's OK to make key markets. Music Pulse, Billboard, Feb. 6) with radio, on the charts, and at music noise again. "For the THE FLYS Here, Billboard cor- haunting art rock full of nuances. video outlets -does not fit the proto- last few years, it wasn't respondents take a Less restrained is thrashabilly trio typical mold, however, and shows no cool to say you were in a global sound -check of Guitar Wolf, whose crazed, over -the- signs of diminishing soon. -

O Caráter Lúdico Da Relação Entre Carlitos E Os Objetos

Cadernos Walter Benjamin 19 O CARÁTER LÚDICO DA RELAÇÃO ENTRE CARLITOS E OS OBJETOS Diogo Rossi Ambiel Facini RESUMO Neste artigo, reflito sobre o caráter lúdico da relação do personagem Carlitos, de Charles Chaplin, com os objetos que o cercam. Em sua relação com objetos, Carlitos dá a eles novas funções e novos sentidos, que ultrapassam aqueles do cotidiano. A aproximação com o campo do lúdico se dá principalmente quando consideramos a atividade de brincar típica das crianças, atividade essa que é comentada por Walter Benjamin em alguns textos. Este artigo é organizado em quatro partes. Primeiramente, é apresentada e discutida a relação entre Carlitos e os objetos. Em segundo lugar, são abordadas algumas noções relacionadas ao conceito de jogo. A seguir, trago algumas reflexões de Walter Benjamin sobre as crianças e as brincadeiras. Por fim, discuto a relação de Carlitos com os objetos em alguns exemplos da obra de Chaplin, retomando algumas ideias trazidas anteriormente. Palavras-chave: Charles Chaplin; Carlitos; Walter Benjamin; Objetos; Jogo. THE PLAYFUL CHARACTER OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CHARLIE AND THE OBJECTS ABSTRACT In this paper, I reflect on the playful character of the relationship between Charles Chaplin’s character Charlie and the objects surrounding him. In his relationship with the objects, Charlie gives them new functions and new senses, which surpass those of everyday life. The approximation with the field of play occurs when one considers the child’s play, an activity that is commented by Walter Benjamin in some texts. This paper is organized in four parts. First, I present and discuss the relationship between Charlie and the objects. -

The Power of Is on Display at Our Marriage Getaways!

MINISTRY NEWS JULY 2021 The Power of is onJ displayesus at our Marriage Getaways! In sharp contrast with our culture, the Bible teaches that the essence of marriage is a sacrificial commitment to the good of the other. That means that love is more fundamentally action than emotion. “ TIM KELLER any people look at photos of Ken and me and say, “Look Oh, how Jesus is needed! When couples cast their cares on at them, they’re always smiling… what a happy couple!” him, they find hope, strength, and a deeper love for Christ and MIn one sense, they are right. Ken and I are very happy. each other. The grace of Jesus empowers a husband and wife to But our smiles do not come easily. Even now, after almost 40 years keep love at the center, even when disability feels overwhelming. of life together, the joy in our marriage is vigorously hard-fought ” Can you see why Joni and Friends Marriage Getaways are for. Ken and I may casually say to one another, “I love you,” but my essential? Where else will these isolated families hear the Gospel quadriplegia keeps demanding that we prove it. of our Savior?! Marriage-love is proved in the middle of the night when When you support our Marriage Getaways, you are helping Ken must get up for the fourth time to help me cough or blow couples discover strength in Christ through their most devastating my nose when I’m sick. For other families with special needs, weaknesses. Disability may expose how desperate needs are, but marriage-love is proved when dad comes home tired from work a Marriage Getaway shows couples where true marriage-love is yet drops everything to tend to their disabled child so mom can found… always in our Lord Jesus. -

MASTER LIST of ROADS and SPEED LIMITS

HAMILTON COUNTY, TENNESSEE 2021 MASTER LIST of ROADS and SPEED LIMITS PREPARED BY PUBLIC WORKS DIVISION TODD E. LEAMON, P.E. ADMINISTRATOR AND COUNTY ENGINEER www.hamiltontn.gov MASTER LIST of ROADS and SPEED LIMITS The Public Works Division does not guarantee the accuracy of or represent that the information contained in this book is correct. In order to determine the correct information, as it presently exists, you should look to other documents, including, but not limited to, subdivision plats, deeds, tax records, court decrees, Hamilton County Board of Commissioners Resolutions, surveys, and any other documents you deem appropriate. You should personally inspect the area for any natural or man-made markers for any assistance they may provide. We make every effort to be as accurate as possible, but for your protection, before you make any decision based upon the information contained herein, you should make an independent examination of all available documents and records. As of this publication there are 867.55 miles of Hamilton County Roadways. Hamilton County Engineering Department Hamilton County Master List of Roads and Speed Limits 1250 Market Street, Suite 3046 Chattanooga, TN 37402 NAME SUBDIVISION QUAD TAX MAP ROW MI SPEED FROM TO RESOL LAST ACTION Abigail Lane Riverbay Estates S/D 112 50 0.46 20 Alexandra Place West and East Turnarounds 616--11 6/1/2016 Academy Place Signal Mountain 080 varies 0.15 West Fairmount Road north Dead End 09--53 9/2/1953 Acres Lane Hunter Acres Estates S/D 140 50 0.07 20 Hunter Hill Court North -

2015 Italian Reining Futurity

ISSUE: NOVEMBER 25, 2015 In this issue: 2015 Italian Reining Futurity Reflections from Ruben van Dorp NRBC Introduces $10,000 Development Division NRHA Futurity & North American Affiliate Championship Show just around the corner! Upcoming 2015-2016 NRHA Events 2015 ITALIAN REINING FUTURITY November 14-22, 2015 Pierluigi Chioldo Claims Italian Reining Horse Association Futurity Championship on Saturday Mizzen The experiment was successful and the challenge has been met. The stands of the large, bright oval arena of the “new Futurity” in Cremona was sold out in and provided an ideal setting to the “reining show” the big Open Final. An impec- cable sound system and a sound track chosen with feeling and intelligence, was supported by a flawless technical staff. And at the top of the podium for levels 4 and 3, a third-gen- eration Italian trainer - 30-year-old Pierluigi Chioldo. His partner in victory in this great adventure, the 2015 Open IRHA / NRHA Futurity, was the magnificent Sat- urday Mizzen, a gelding by Saturday night Custom and Westcoast Mizzen bred by Ambrosini QH in Pontoglio (Brescia). We could almost call this the “geldings’ Futuri- ty”, as once again a gelding dominated the ranking, show- Pierluigi Chioldo and Saturday Mizzen ing how this condition can really bring out the best from certain types of horse, helping to avoid unnecessary risks ponent to beat: the great Bernard Fonck, who had marked a and conferring a special kind of serene energy that may be resounding 223, giving full expression to the power of Sev- an advantage in the show pen. -

Mortuary File.Xlsx

Index to the Mortuary Files of Valente, Marini, Perata & Co 3448 Mission Street, San Francisco Mortuary Books are located in the Colma Historical Museum 1500 Hillside Blvd, Colma Index by The San Mateo County Genealogical Society (Lauren Perritt, Russ & Eunice Brabec, Jean Ann Carroll, Cath Trindle) This is a work in progress the records to be indexed cover the years the years 1888-1964 Some books are numbered the early ones are titled only by the years they cover. For ease of indexing we have given them a letter designation. The books included in this first installment include: Notes: Date given is death date if know, otherwise it might be burial date, date plot was purchased or date at the top of the page. In the case of removals from one cemtery to another the date is given in the notes column to avoid confusion over death dates. In the case of stillbirths and infants, the name given might be that of a parent, the records were often not clear. Remember, this is an index not an extraction, the actual record is likely to contain additional information, including who is responsible for payment, some societies the individual belonged to, names of newspapers where notices were places, and in some journals prior to 1920 obituaries might be attached. There is some duplication in the records, some of the Journal were most likely copied to the later books. We chose to include both because these were the years that might also have attached obituaries. When requesting a copy from the Colma Historical Society, be sure to copy the book volume and page number carefully. -

Queens Today

Volume 65, No. 65 Tuesday, July 16, 2019 50¢ City jails plan approaches an QUEENS uncertain vote By David Brand and Noah Goldberg Queens Daily Eagle The community boards have voted and TODAY the borough presidents have weighed in. — JULY 16, 2019 — The city’s plan to close Rikers Island jails by 2026 — by building four new bor- ough-based facilities via an unprecedented BOROUGH PRESIDENT MELINDA land use measure — has moved out of the Katz leads public defender Tiffany Cabán advisory stage and into the legally binding by just 16 votes in the Democratic Primary phase as it approaches a fall vote by the City for Queens DA. That number will likely Council. shift one way or another, with a countywide The plan calls for building a new 1,150- recount underway at a Board of Elections bed jail in every borough except Staten Is- facility in Middle Village . See page 16 for land and likely depends on the support of the story. the four councilmembers who represent the neighborhoods in question: Karen Koslow- itz, who represents Kew Gardens in Queens; MORE THAN 200 RIDERS, INCLUDING Stephen Levin, who represents Boerum two local lawmakers, pedaled through the Hill in Brooklyn; Margaret Chin, who rep- resents Manhattan’s Chinatown; and Diana parks and pathways of Eastern Queens Councilmember Karen Koslowitz maintains support for the jails plan, though she is Saturday for the third annual Tour de Continued on page 7 Flushing. Read more on page 10. advocating for a smaller facility in Kew Gardens. Photo via the MTA/Flickr STATE SEN. -

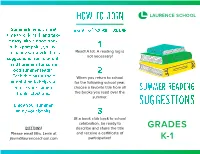

Suggestions from Students and Librarians for Some Good Summer Reading

HOW TO JOIN Summertime is a great MRs. WOLKE/JACOBSON'S BOOK CLUB time to kick back and take it easy with a good book. In this pamphlet, you will 1 find some wonderful book Read! A lot. A reading log is not necessary! suggestions from students and librarians for some good summer reading. 2 Each title has a short When you return to school annotation to help you for the following school year, choose your summer choose a favorite title from all SUMMER READING book selections. the books you read over the summer. Enjoy your summer, SUGGESTIONS enjoy your books! 3 At a book club back to school celebration, be ready to Questions? describe and share the title GRADES Please email Mrs. Levin at and receive a certificate of [email protected] participation! K-1 SUMMER READING SUGGESTIONS Across the Bay Evelyn Del Rey is I Dream of Popo Lift Respect: Aretha Your Name is a Song Carlos Aponte Moving Away Livia Blackburne Minh Lê Franklin the Queen of Jamilah Thompkins- ISBN: 978-1524786625 Meg Medina ISBN: 978-1250249319 ISBN: 978-1368036924 Soul Bigelow ISBN: 978-1536207047 When a young girl and Iris loves to push the Carole Boston ISBN: 978-1943147724 Life in his hometown is Weatherford cozy as can be, but the The story of two girls her family emigrate elevator buttons in her Frustrated by a day full of ISBN: 978-1534452282 call of the capital city pulls who will always be each from Taiwan to America, apartment building. teachers and classmates Carlitos across the bay in other’s número uno, even she leaves behind her Suddenly, a mysterious This authoritative, mispronouncing her search of his father. -

AZ Showdown Final Processed

Division Weight Class First Name Last Name Team 6U 37 Peyton Chelewski Colorado Outlaws 6U 37 Kemp Enriquez Team Texas 6U 37 Zane Enriquez Team Texas 6U 37 Gunner Kelly Team Aggression 6U 37 Emily Lawrence Team Aggression 6U 37 Steven Peralta Lockjaw WC 6U 37 carter shanley-martinez duran elite 6U 40 Troy Blevins Punisher Wrestliing co 6U 40 Sophie Hayman Hemet WC 6U 40 Charlotte Jarman Thorobred WC 6U 40 Gunner Kelly Team Aggression 6U 40 Daniel Khachatryan Dethrone 6U 40 Ashton Mazon Prescott Valley Bighorns 6U 40 Fermin Palacios NM Beast 6U 40 Camren Redwine NM WolfPack 6U 40 Leonardo Romero Ramos Gold Rush 6U 40 Presley Salcedo Roundhousewrestling 6U 40 Benjamin Schimmel NM WolfPack 6U 43 JD Alguire NM WolfPack 6U 43 Troy blevins Punisher Wrestliing co 6U 43 Chase Chelewski Colorado Outlaws 6U 43 Conrad Frascone Prescott Raider Wrestling 6U 43 Dane Parsons Pomona Elite 6U 43 Leonardo Romero Ramos Gold Rush 6U 43 Presley Salcedo Roundhousewrestling 6U 43 Amaya Smith 505 WC 6U 43 Brantley Wagner PV Bighorns 6U 43 Jax Williams Tuff Kidz WC 6U 46 Zander King Agcaoili Gold Rush 6U 46 Aaron Arroyos Team Texas 6U 46 Liam Howarth Colorado Regulators 6U 46 Oscar Mortensen AWC 6U 46 Landyn Stills Battle Born Wr Ac 6U 46 Caleb Stone NM WolfPack 6U 46 Redek Voss Roseburg Mat Club 6U 49 Joseph De La Rosa Grindhouse 6U 49 Tommy Gentry NM Beast 6U 49 Dallin Hare Stout Wr Ac 6U 49 Liam Howarth Colorado Regulators 6U 49 Jace Lopez NM Gold 6U 49 Grayson Maddux Umpqua WC 6U 49 Weston Phillips USA Gold 6U 49 Roan Rickel Team Aggression 6U 49 Zephyr Salas