Employability of Unfettered Jobs in the Cattle Sector of the Bamenda Grassfields in Cameroon, 1916-2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joshua Osih President

Joshua Osih President THE STRENGTH OF OUR DIVERSITY PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION 2018 JOSHUA OSIH | THE STRENGTH OF OUR DIVERSITY | P . 1 MY CONTRACT WITH THE NATION Build a new Cameroon through determination, duty to act and innovation! I decided to run in the presidential election of October 7th to give the youth, who constitute the vast majority of our population, the opportunity to escape the despair that has gripped them for more than three decades now, to finally assume responsibility for the future direction of our highly endowed nation. The time has come for our youth to rise in their numbers in unison and take control of their destiny and stop the I have decided to run in the presidential nation’s descent into the abyss. They election on October 7th. This decision, must and can put Cameroon back on taken after a great deal of thought, the tracks of progress. Thirty-six years arose from several challenges we of selfish rule by an irresponsible have all faced. These crystalized into and corrupt regime have brought an a single resolution: We must redeem otherwise prosperous Cameroonian Cameroon from the abyss of thirty-six nation to its knees. The very basic years of low performance, curb the elements of statecraft have all but negative instinct of conserving power disappeared and the citizenry is at all cost and save the collapsing caught in a maelstrom. As a nation, system from further degradation. I we can no longer afford adequate have therefore been moved to run medical treatment, nor can we provide for in the presidential election of quality education for our children. -

Programming of Public Contracts Awards and Execution for the 2020

PROGRAMMING OF PUBLIC CONTRACTS AWARDS AND EXECUTION FOR THE 2020 FINANCIAL YEAR CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING LOGBOOK OF DEVOLVED SERVICES AND OF REGIONAL AND LOCAL AUTHORITIES NORTH-WEST REGION 2021 FINANCIAL YEAR SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of No Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts No. page contracts REGIONAL 1 External Services 9 514 047 000 3 6 Bamenda City Council 13 1 391 000 000 4 Boyo Division 9 Belo Council 8 233 156 555 5 10 Fonfuka Council 10 186 760 000 6 11 Fundong Council 8 203 050 000 7 12 Njinikom Council 10 267 760 000 8 TOTAL 36 890 726 555 Bui Division 13 External Services 3 151 484 000 9 14 Elak-Oku Council 6 176 050 000 9 15 Jakiri Council 10 266 600 000 10 16 Kumbo Council 5 188 050 000 11 17 Mbiame Council 6 189 050 000 11 18 Nkor Noni Council 9 253 710 000 12 19 Nkum Council 8 295 760 002 13 TOTAL 47 1 520 704 002 Donga Mantung Division 20 External Services 1 22 000 000 14 21 Ako Council 8 205 128 308 14 22 Misaje Council 9 226 710 000 15 23 Ndu Council 6 191 999 998 16 24 Nkambe Council 14 257 100 000 16 25 Nwa Council 10 274 745 452 18 TOTAL 48 1 177 683 758 Menchum Division 27 Furu Awa Council 4 221 710 000 19 28 Benakuma Council 9 258 760 000 19 29 Wum Council 7 205 735 000 20 30 Zhoa Council 5 184 550 000 21 TOTAL 25 870 755 000 MINMAP/Public Contracts Programming and Monitoring Division Page 1 of 37 SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of No Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts No. -

Dynamics of Indigenous Socialization Strategies and Emotion Regulation Adjustment Among Nso Early Adolescents, North West Region of Cameroon

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 3, Issue 8, August 2016, PP 86-124 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.0308009 www.arcjournals.org Dynamics of Indigenous Socialization Strategies and Emotion Regulation Adjustment among Nso Early Adolescents, North West Region of Cameroon Therese Mungah Shalo Tchombe Ph.D. Emeritus Professor of Applied Cognitive Developmental Psychology, UNESCO Chair for Special Needs Education, University of Buea, Cameroon P.O. Box 63 Director, Centre for Research in Child and Family Development & Education (CRCFDE) P.O. Box 901, Limbe, Cameroon Tani Emmanuel Lukong, Ph.D. Lecturer, University of Buea, Founder, “Foundation of ScientificResearch, Community Based Rehabilitation and Advocacy on Inclusive Education” (FORCAIE-CAMEROON) [email protected] Abstract: Cultural values vary across cultures and social ecologies. Cultural communities define and endorse human abilities they perceive to give expression to their core values. This study aimed to examine the interaction among specific indigenous strategies of socialization such as indigenous proverbs, and indigenous games) within an eco-cultural setting which dictate a more cultural specific dimension on emotion regulation adjustment with keen attention on social competence skills and problem solving skills through an indigenized conceptual model of the Nso people of Cameroon. The study had three objectives; the study had a sample of 272. Results indicate that, proverbs -

JAKIRI COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT PLAN Kumbo, the ………………………

REPUBLIQUE a DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON PAIX- TRAVAIL- PATRIE PEACE- WORK-FAHERLAND ----------------------------- ----------------------------- MINISTERE DE L’ADMINISTRATION MINISTRY OF TERRITORIAL ADMINSTRATION TERRITORIALE ET AND DECENTRALISATION DECENTRALISATION ----------------------------- ----------------------------- NORTH WEST REGION REGION DU NORD OUEST ----------------------------- ----------------------------- BUI DIVISION DEPARTEMENT DE BUI ----------------------------- -------------------------- JAKIRI COUNCIL COMMUNE DE JAKIRI ----------------------------- ------------------------------- [email protected] Kumbo, the ………………………. Email: [email protected] COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT PLAN Kumbo, the ………………………. Elaborated with the Technical and Financial Support of the National Community Driven Development Program (PNDP) June 2012 i JAKIRI COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT PLAN Elaborated and submitted by: Sustainable Integrated Balanced Development Foundation (SIBADEF), P.O.BOX 677, Bamenda, N.W.R, Cameroon, Tel: (237) 70 68 86 91 /98 40 16 90 / 33 07 32 01, E-mail: [email protected] June 2012 ii Table of content Table of content ....................................................................................................................................................... iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................. viii 1.NTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................... -

OXIDATION PHENOMENON of FERROUS to FERRIC IRON in WATER SOURCES of BUI DIVISION, NORTH WEST REGION of CAMEROON (Case Study of Mbiame Water Catchment)

ISSN 2394-9716 International Journal of Novel Research in Interdisciplinary Studies Vol. 6, Issue 2, pp: (10-15), Month: March - April 2019, Available at: www.noveltyjournals.com OXIDATION PHENOMENON OF FERROUS TO FERRIC IRON IN WATER SOURCES OF BUI DIVISION, NORTH WEST REGION OF CAMEROON (Case study of Mbiame water catchment) 1Fondzenyuy Vitalis Fonfo, 2Kengni Lucas 1,2 University of Dschang, Faculty of Science. Department of Earth Sciences, P.O Box 67 Dschang. Abstract: Oxidation is accompanied by addition of oxygen or a loss of electron by a species. Aluminium and iron were dominant heavy metals in Bui water bodies. Iron has two oxidation states (Fe2+ and Fe3+). Fe3+ is more stable, accounted for by the stability of electrons in its atomic orbitals, whereas the unstable state converts to the more stable form. Oxidation was observed in Bui water sources, very pronounced at Mbiame catchment in Mbven subdivision. The consequence of this oxidation phenomenon was the predominanance of a reddish–brownish colouration. This was glaring as water samples changed colour from greenish to reddish on exposure in a beaker few minutes after sampling indicating intense aerial oxidation. This phenomenon is characteristic of transition metals with variable oxidation states and produce coloured solutions. The process expressed in this article does not compromise water quality. The concentrations Al and Fe remained within suitable limits for water consumption, stipulated in norms such as the World Health Organisation (WHO, 2004, 2008). A paradigm shift is made from the assertion wherein coloured water was generally considered unsuitable for human consumption particularly drinking. Keywords: water colouration, ferrous and ferric iron, transition metals. -

Cartography of the War in Southern Cameroons Ambazonia

Failed Decolonization of Africa and the Rise of New States: Cartography of the War in Southern Cameroons Ambazonia Roland Ngwatung Afungang* pp. 53-75 Introduction From the 1870s to the 1900s, many European countries invaded Africa and colonized almost the entire continent except Liberia and Ethiopia. African kingdoms at the time fought deadly battles with the imperialists but failed to stop them. The invaders went on and occupied Africa, an occupation that lasted up to the 1980s. After World War II, the United Nations (UN) resolution 1514 of 14 December 1960 (UN Resolution 1415 (1960), accessed on 13 Feb. 2019) obliged the colonial powers to grant independence to colonized peoples and between 1957 and 1970, over 90 percent of African countries got independence. However, decolonization was not complete as some colonial powers refused to adhere to all the provisions of the above UN resolution. For example, the Portuguese refused to grant independence to its African colonies (e.g. Angola and Mozambique). The French on their part granted conditional independence to their colonies by maintaining significant ties and control through the France-Afrique accord (an agreement signed between France and its colonies in Africa). The France-Afrique accord led to the creation of the Franc CFA, a currency produced and managed by the French treasury and used by fourteen African countries (African Business, 2012). CFA is the acronym for “Communauté Financière Africaine” which in English stands for “African Financial Community”. Other colonial powers violated the resolution by granting independence to their colonies under a merger agreement. This was the case of former British Southern Cameroons and Republic of Cameroon, South Sudan and Republic of Sudan, Eritrea and Ethiopia, Senegal and Gambia (Senegambia Confederation, 1982-1989). -

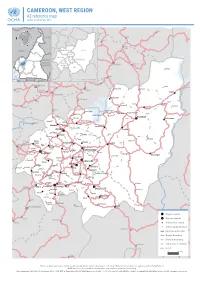

CAMEROON, WEST REGION A3 Reference Map Update of September 2018

CAMEROON, WEST REGION A3 reference map Update of September 2018 Nwa Ndu Benakuma CHAD WUM Nkor Tatum NIGERIA BAMBOUTOS NOUN FUNDONGMIFI MENOUA Elak NKOUNG-KHI CENTRAL H.-P. Njinikom AFRICAN HAUT- KUMBO Mbiame REPUBLIC -NKAM Belo NDÉ Manda Njikwa EQ. Bafut Jakiri GUINEA H.-P. : HAUTS--PLATEAUX GABON CONGO MBENGWI Babessi Nkwen Koula Koutoukpi Mabouo NDOP Andek Mankon Magba BAMENDA Bangourain Balikumbat Bali Foyet Manki II Bangambi Mahoua Batibo Santa Njimom Menfoung Koumengba Koupa Matapit Bamenyam Kouhouat Ngon Njitapon Kourom Kombou FOUMBAN Mévobo Malantouen Balepo Bamendjing Wabane Bagam Babadjou Galim Bati Bafemgha Kouoptamo Bamesso MBOUDA Koutaba Nzindong Batcham Banefo Bangang Bapi Matoufa Alou Fongo- Mancha Baleng -Tongo Bamougoum Foumbot FONTEM Bafou Nkong- Fongo- -Zem -Ndeng Penka- Bansoa BAFOUSSAM -Michel DSCHANG Momo Fotetsa Malânden Tessé Fossang Massangam Batchoum Bamendjou Fondonéra Fokoué BANDJOUN BAHAM Fombap Fomopéa Demdeng Singam Ngwatta Mokot Batié Bayangam Santchou Balé Fondanti Bandja Bangang Fokam Bamengui Mboébo Bangou Ndounko Baboate Balambo Balembo Banka Bamena Maloung Bana Melong Kekem Bapoungué BAFANG BANGANGTÉ Bankondji Batcha Mayakoue Banwa Bakou Bakong Fondjanti Bassamba Komako Koba Bazou Baré Boutcha- Fopwanga Bandounga -Fongam Magna NKONGSAMBA Ndobian Tonga Deuk Region capital Ebone Division capital Nkondjock Manjo Subdivision capital Other populated place Ndikiniméki InternationalBAF borderIA Region boundary DivisionKiiki boundary Nitoukou Subdivision boundary Road Ombessa Bokito Yingui The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. NOTE: In places, the subdivision boundaries may suffer of significant inacurracy. Date of update: 23/09/2018 ● Sources: NGA, OSM, WFP ● Projection: WGS84 Web Mercator ● Scale: 1 / 650 000 (on A3) ● Availlable online on www.humanitarianresponse.info ● www.ocha.un.org. -

Cameroon 2019 International Religious Freedom Report

CAMEROON 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution establishes the state as secular, prohibits religious harassment, and provides for freedom of religion and worship. According to media, security officers combating Anglophone separatists in the Northwest and Southwest Regions killed Christians and clergymen and attacked places of worship. In April soldiers shot and killed a Baptist pastor on his way to church in Mfumte Village. In September soldiers shot and killed a woman outside the Roman Catholic church in Bambui. In May security forces set fire to a Protestant church during clashes with separatists in Bamenda, the Northwest Region’s capital. In October security forces arrested a Catholic priest in Bamenda, reportedly because he accused soldiers of human rights abuses during an address to the United Nations, according to one of his colleagues. He was released a day later. Religious media outlets accused the government of arming Muslim herders and encouraging them to attack Christians in the town of Wum, and of exploiting sporadic clashes over land between Mbororo herders and local farmers, attempting to introduce a religious character to the conflict in the Northwest Region between security forces and separatists. In February police briefly detained a pastor of the Cameroon Evangelical Church (CEC) and accused him of inciting rebellion during a sermon. On several occasions, Christians in the Northwest and Southwest Regions said security forces interrupted church services and prevented them from accessing places of worship. During the year, the government appointed a board to manage the CEC’s affairs. The government said it acted to preserve order within the CEC, which was undergoing an internal dispute over the election of Church leaders after the government suspended elected executives. -

P.O Box 8, Kumbo Bui Division, North West Region Cameroon Tel: (237) 242659959, 653807563, 695454509 Website: Www

Mission: To See and Serve Christ in All by Spending Time to Care P.O Box 8, Kumbo Bui Division, North West Region Cameroon Tel: (237) 242659959, 653807563, 695454509 Website: www. Shisonghospital.org Email: [email protected] Cardiac Centre: (237) 69690 –1264, 69948-8412, 67753-6572 54 Table of Contents Some abbreviations……………………………………………………………….….3 CONCLUSION Word from the Hospital Director…………………………………………………….3 Section One: General presentation This year 2015 was characterised with a lot of activites and achievements Brief History of the hospital…………………………………. ……………………..4 thanks to the great collaboration of our stakeholders. These achievements Staff composition…………………………………………………………………….6 Doctors and responsibilities…………………………………………………………7 were however recorded amidst some challenges. This year also witnessed the Celebration of St. Elizabeth of Hungary feast day………………………………….8 handing over of the baton by Sr. Ebamu Ruphina (Matron) to Sr. Kinyuy Some significant events within the year……………………………………………..8 The CAMNOWAA scientific conference…………………………………………...9 Mary Aldrine (Director) for continuity of the vision of the institution. It is Infrastructural Achievements ……………………………………………………….9 thanks to the collaboration of the departmental charges of the Hospital and Staff Retirement Celebration 2015…………………………………………………10 Small Christian Community………………………………………………………..11 chief of our satellite Health Centres this report has been realized. Gratitude Some visitors in 2015……………………………………………………………….11 goes to God Almighty for his continues -

2018 Annual Report

Hope for the Better Future Cooperative (H4BF) 2018 Annual Report Contact: +237671977678/ +237 670363968 Email: [email protected], Website: www.h4bfcooperative.com FORWARD FROM THE EXECUTIVE DDIRECTOR The year 2018 has been an extra ordinary year with H4BF which saw her extend must of her activities to other regions within the country and of course create more impact in the communities where we work to realize our very important mission. The year began with the launching of the 2018 activities which brought together so many partners, local authorities and community participants. We also used the opportunity to invite a variety of media houses that covered the events to give H4BF and her partners a wider audience. In the course of the year 2018, we focused on expanding our activities especially our community water and sanitation projects to communities that faced great water challenges while putting more efforts on sensitization through schools and other community units. We did not leave out the agricultural sector which is the backbone of H4BF activities and so many other activities including environmental advocacy, tree planting, food exchange programs etc. This year, we also received over 8 volunteers including national and international volunteers from universities, high schools and local communities. These contributed a lot to the accomplishments this year. Our team also increased as we recruited more local contact persons who have been acting as managers in our community projects. Our online community have also greatly increased through the increasing hard work put in by our agile public relations department which is a huge plus to us and our partners. -

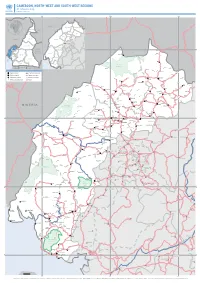

CAMEROON, NORTH-WEST and SOUTH-WEST REGIONS A1 Reference Map Update of June 2018

CAMEROON, NORTH-WEST AND SOUTH-WEST REGIONS A1 reference map Update of June 2018 9.0°E 10.0°E 11.0°E NIGERIA DONGA-MANTUNG EXTRÊME-NORD MENCHUMMENCHUM DONGA-MANTUNG FAR-NORTH CHAD BOYO BOYO BUIBUI MEZAM NGO- MOMOMOMO MEZAM NGOKETUNJIA-KETUNJIA NORTHNORD NIGERIA MANYUMANYU LEBIALEMLEBIALEM ADAMAOUAADAMAOUA NORTH- KUPE- 7.0°N NORD-OUEST-WEST CENTRAL -MUANENGUBA KUPE-MUANENGUBA Abonshie WESTOUEST AFRICAN SOUTH- SUD-OUEST REPUBLIC -WEST NDIANNDIAN Buku CENTRECENTRE Furu Awa LITTORALLITTORAL MEMEMEME EASTEST Ako SOUTHSUD FAKOFAKO Kimbi-Fungom EQ. Natianal Park GABON Akwaja GUINEA CONGO Munkep Dumbu Adere Ande Jevi Berabe Region capital International border Lus Kom Division capital Region boundary Subdivision capital Division boundary Abar NKAMBE Mfom Esu Misaje Ntong Other populated place Road Binka Iyahe Zhoa Akumaye Baworo Fonfuka Gom Ballin Nwa Yang Weh Kumfutu Mbwat Benade Lassin Ngale Ndu Benakuma Rom Benagudi Konene WUM Kuk Nkor Akwaya Sabongari Mmen Tatum Ntumbaw Modelle Aduk Ngu Nkim Assaka Ajung Befang Ntem Bu Tinta FUNDONG Mbonso Mbenkas Elak Shishong Njinikom Obang Dzeng Takamanda Mbakong KUMBO NIGERIA Mbiame Nskumba Ayi Mejang Natianal Park Tingoh Belo Ote Njikwa Oshie Babanki Ibal Tava Ngwo Tugi Bafut Jakiri Babungo Akwa Akanunku Tinachong Lip Bambui Sabga 6.0°N Mbu MBENGWI Baba I Babessi Dadi Menka Bambili NDOP 6.0°N Andek Kajifu Acha Tugui Mankon Nkwen Nyang Bamessing Bangolan Magba Ebinsi Teze Abebung BAMENDA Olorunti Kai Bangourain Akum Bambalang Oshum Balikumbat Agborkem Widikum Bali Mukoyong Bamukumbit Baliben Njimom Batibo -

Typology of Local Construction Materials from the Adamawa and North-West Regions of Cameroon

Geomaterials, 2016, 6, 50-59 Published Online April 2016 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/gm http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/gm.2016.62005 Typology of Local Construction Materials from the Adamawa and North-West Regions of Cameroon Zo’o Zame Philémon1, Nzeukou Nzeugang Aubin2*, Uphie Chinje Melo2, Mache Jacques Richard2, Ndifor Divine Azigui3, Nni Jean3 1Department of Earth Sciences, University of Yaoundé, Yaoundé, Cameroon 2Local Materials Promotion Authority (MIPROMALO), Yaoundé, Cameroon 3National Civil Engineering Laboratory (LABOGENIE), Yaoundé, Cameroon Received 2 March 2016; accepted 22 April 2016; published 25 April 2016 Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract This article summarizes the different local construction materials observed in two regions of Ca- meroon (Adamawa and North-West). These raw materials were mapped and evaluated using var- ious methods of investigation (spatial distribution, estimation of reserves, development of a da- tabase compatible with geo-referenced maps). The results obtained show three types of local con- struction materials (vegetal, pedological and geological) with quantitative estimation or distribu- tion. Vegetal local materials include herbaceous savanna with strong dominance of straw in Ada- mawa region than the North West region. Pedological local construction materials include lateritic soils (ferruginous or clayey), harplan, sandy clay and sandy clay soil while geological local con- struction materials include volcanic, plutonic and metamorphic rocks. Many sites of these geolog- ical materials are suitable for the rock quarry plant. Adamawa region also contains sedimentary rocks constituted by metamorphic conglomerate and sandstones.