Charles M. Netterström House 833 W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PGL Exhibit 5.02

3/15/2021 Chicago Landmarks - Map Details PGL Ex. 5.02 Maps Home Northwest & West Far South Loop Near North Near South, South & Southwest North Northwest & West Individual Landmarks Landmark Districts webapps1.chicago.gov/landmarksweb/web/regiondetails.htm?regId=2 1/2 3/15/2021 Chicago Landmarks - Map Details 1. Beeson House and Coach House 1. Five Houses on Avers Avenue district PGL Ex. 5.01 2. Congress Theater 2. Jackson Boulevard district 3. F.R. Schock House 3. Ukrainian Village district 4. First Baptist Congregational Church 4. Wicker Park district 5. Goldblatt Bros. Department Store 6. Groesbeck House 7. Hitchcock House 8. Holy Trinity Orthodox Cathedral and Rectory 9. Humboldt Park Boathouse Pavilion 10. Jewish People's Institute 11. King-Nash House 12. Laramie State Bank Building 13. Metropolitan Missionary Baptist Church 14. Northwestern University Settlement House 15. Peoples Gas Irving Park Neighborhood Store 16. Race House 17. Rath House 18. Schlect House 19. Schurz High School 20. Sears, Roebuck and Company Administration Building 21. St. Ignatius College Prep Building 22. Thalia Hall 23. Waller Apartments 24. Walser House 25. West Town State Bank Building 26. Whistle Stop Inn Home : Disclaimer : Privacy Policy : Web Standards : Contact Us Copyright © 2010 – 2021 City of Chicago webapps1.chicago.gov/landmarksweb/web/regiondetails.htm?regId=2 2/2 3/15/2021 Illinois Archaeological Predictive Model Illinois Archaeological Predictive Model Illinois State Archae + 1241 W Division St, Chicago, IL, Layer List – Show search results for 1241 W Divisi… 5 6 7 8 9 10 PGL Ex. 5.01 Major Lakes States IL Counties Search result 1241 W Division St, Chicago, IL, 60642, USAIL cities Zoom to Watersheds IAPM prob Probability 1 (High) - 0 (Low) IAPM prob reclassified Probability (reclassified) High (> 0.75) Med-High (0.5-0.75) Med-Low (0.25-0.5) 00 300300 600ft600ft Low (< 0.25) https://univofillinois.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=c6954311e2584aab837a389ddcca92cb 1/1. -

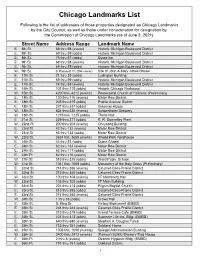

Chicago Landmarks Address List

Chicago Landmarks List Following is the list of addresses of those properties designated as Chicago Landmarks by the City Council, as well as those under consideration for designation by the Commission of Chicago Landmarks (as of June 3, 2021). Street Name Address Range Landmark Name E. 8th St. 68 thru 98 (evens) Historic Michigan Boulevard District E. 8th St. 69 thru 99 (odds) Historic Michigan Boulevard District E. 8th St. 75 thru 87 (odds) Essex Inn E. 9th St. 68 thru 98 (evens) Historic Michigan Boulevard District E. 9th St. 69 thru 99 (odds) Historic Michigan Boulevard District W. 9th St. S. Plymouth Ct. (SW corner) Site of John & Mary Jones House E. 11th St. 21 thru 35 (odds) Ludington Building E. 11th St. 69 thru 99 (odds) Historic Michigan Boulevard District E. 11th St. 74 thru 98 (evens) Historic Michigan Boulevard District E. 14th St. 101 thru 115 (odds) Historic Chicago Firehouse W. 15th St. 4200 thru 4212 (evens) Pentecostal Church of Holiness (Preliminary) E. 18th St. 100 thru 116 (evens) Motor Row District E. 18th St. 205 thru 315 (odds) Prairie Avenue District E. 18th St. 221 thru 237 (odds) Glessner House W. 18th St. 524 thru 530 (evens) Schoenhofen Brewery W. 18th St. 1215 thru 1225 (odds) Thalia Hall E. 21st St. 339 thru 371 (odds) R. R. Donnelley Plant W. 22nd Pl. 200 thru 208 (evens) On Leong Building E. 23rd St. 42 thru 132 (evens) Motor Row District E. 23rd St. 63 thru 133 (odds) Motor Row District W. 23rd St. 3634 thru 3658 (evens) Shedd Park Fieldhouse E. -

Commission on Chicago Landmarks

COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS The Miracle House, 2001 N. Nordica Ave., 1954, Belli & Belli Architects and Engineers, Inc. CHICAGO LANDMARKS Individual Landmarks and Landmark Districts designated as of May 27, 2021 City of Chicago Lori E. Lightfoot, Mayor Department of Planning and Development Commission on Chicago Landmarks Maurice D. Cox, Commissioner Ernest Wong, Chairman Bureau of Citywide Systems & Historic Preservation Kathy Dickhut, Deputy Commissioner Chicago Landmarks are those buildings, sites, objects, or districts that have been officially designated by the City Council. They are recommended for landmark designation by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, a nine-member board appointed by the Mayor and City Council. The Commission is also responsible for reviewing any proposed alteration, demolition, or new construction affecting individual landmarks or landmark districts. The date the landmark was designated is shown in parentheses. 2 INDIVIDUAL LANDMARKS (365 Total) 1. Dr. Wallace C. Abbott House ~ 4605 N. Hermitage Ave. 1891; Dahlgren and Lievendahl. Rear Addition: 1906; architect unknown. (March 1, 2006) 2. Jessie and William Adams House ~ 9326 S. Pleasant Ave.; 1901; Frank Lloyd Wright. (June 16, 1994) 3. Jane Addams’ Hull House and Dining Room ~ 800 S. Halsted St; House: 1856; architect unknown. Dining Hall: 1905; Pond and Pond. (June 12, 1974) 4. All Saints Church and Rectory ~ 4550 N. Hermitage Ave.; 1883; John C. Cochrane. (December 27, 1982) 5. Allerton Hotel ~ 701 N. Michigan Ave.; 1922; Murgatroyd & Ogden with Fugard & Knapp. (April 29, 1998) 6. American Book Company Building ~ 320-330 E. Cermak Rd.; 1912, Nelson Max Dunning. (July 29, 2009) 7. American School of Correspondence ~ 850 E. -

Chicago Landmarks List

Chicago Landmarks List Following is the list of addresses of those properties designated as Chicago Landmarks by the City Council, as well as those under consideration for designation by the Commission of Chicago Landmarks (as of February 4, 2021). Street Name Address Range Landmark Name E. 8th St. 68 thru 98 (evens) Historic Michigan Boulevard District E. 8th St. 69 thru 99 (odds) Historic Michigan Boulevard District E. 8th St. 75 thru 87 (odds) Essex Inn E. 9th St. 68 thru 98 (evens) Historic Michigan Boulevard District E. 9th St. 69 thru 99 (odds) Historic Michigan Boulevard District W. 9th St. S. Plymouth Ct. (SW corner) Site of John & Mary Jones House E. 11th St. 21 thru 35 (odds) Ludington Building E. 11th St. 69 thru 99 (odds) Historic Michigan Boulevard District E. 11th St. 74 thru 98 (evens) Historic Michigan Boulevard District E. 14th St. 101 thru 115 (odds) Historic Chicago Firehouse W. 15th St. 4200 thru 4212 (evens) Pentecostal Church of Holiness (Preliminary) E. 18th St. 100 thru 116 (evens) Motor Row District E. 18th St. 205 thru 315 (odds) Prairie Avenue District E. 18th St. 221 thru 237 (odds) Glessner House W. 18th St. 524 thru 530 (evens) Schoenhofen Brewery W. 18th St. 1215 thru 1225 (odds) Thalia Hall E. 21st St. 339 thru 371 (odds) R. R. Donnelley Plant W. 22nd Pl. 200 thru 208 (evens) On Leong Building E. 23rd St. 42 thru 132 (evens) Motor Row District E. 23rd St. 63 thru 133 (odds) Motor Row District W. 23rd St. 3634 thru 3658 (evens) Shedd Park Fieldhouse E. -

Map of Chicago Landmarks

Citywide Historic Resources - HOWARD HOWARD HOWARD RS 95 Individual E G E O ! R L Y TOUHY TOUHY TOUH TOUHY G A E N 161 L 51 O 158 I ! !R ! D O PRATT PRATT N A N Landmarks E L E I O H Z M A S 199 D C A K A A 13 E L D ! D P W K DEVON ! A E E L R L 11 L K N O 223 I ! O E S 280 176 R R M ! N O E ! A ! E C I D PETERSON PETERSON D PETERSON C 270 E L 91 PETERSON IN 128 N C I ! S O ! ! T ! R E LN S M D G I 277 E O U 224 85 N KE R 103 E NNED L Y A A ! H Y WR KENNED G MAWR BRYN MA L BRYN L ! ! ! 28 231 N N A A E O R N N R L R E ! 90 ! T 36 A H T O 139 B A I W I M § N 321 M ¨¦ E R N ! E E ! S U L O T R R S C ! M C T E R O FOSTE E E FOSTER TER O V FOS F L N D 285 I I R K 227 R E L R E FOSTER R A L N A ! N T A A H ! S C T S K P 110 S A E K E E O I ! NCE RE S A LAW K 334226 M H O K A ! N LAWRENCE 143 O R R ! R 43 O R E A A 304 D E D 186 L ! P N ! N N 133 T L ! E A ! S A 15 L 86 ! E R O ONTROS M R R ! 131 A T K E ! L E I N B C Z ! E D M C E U L I 345 K C 317 N 258 108 IRVING PARK 157 !! C 38 ! ! O !! L C N L I 250 170 106 A F 50 I ! K C !! ! E A S P ON 351 5 44 ADDIS H E L ! O E ! R O ! I L C E I R G F N O A I 49 I 208 C N C T L A S ! ! 290 29 A P 288 BELMONT U 120 R A K E ! ! 82 L ! ! M G I E ! K LW M A I N R A C I E N 94 K U 33 A L C L K Y S P DIVERSEY E A R 335 B 25 ! A ! E O K R A L R U T A H ! U ! E K R T 324 O E 121 P 109 N N E N 232 T N S 30 ! 175 E ! S ! D N ! Y O A ! LERTON ! FUL 184 E 123 14 GRAND K X G A P 265 I 180 A ! R ! ! E N R ! S ! R S 193 R G RAN 73 O A D E F ITAG ! ARM N I ! ARMITAGE L 279 ARMITAGE 287 K A 77 164 209 K 268 E ! C !