Chetco Bar Fire Salvage Project Final Environmental Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chetco Bar BAER Specialist Reports

Chetco Bar BAER Specialist Reports Burned Area Emergency Response Soil Resource Assessment Chetco Bar Fire OR-RSF-000326 Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest October 2017 Lizeth Ochoa – BAER Team Soil Scientist USFS, Rogue River-Siskiyou NF [email protected] Kit MacDonald – BAER Team Soil Scientist USFS, Coconino and Kaibab National Forests [email protected] 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Chetco Bar fire occurred on 191,197 acres on the Gold Beach and Wild Rivers Ranger District of the Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest, BLM lands, and other ownerships in southwestern Oregon. Approximately 170,321 acres of National Forest System (NFS) land, 6,746 acres of BLM land and 14,130 acres of private land were affected by this wildfire. Within the fire perimeter, approximately 14,012 acres burned at high soil burn severity, 64,545 acres burned at moderate soil burn severity, 76,613 acres burned at low soil burn severity, and 36,027 remain unburned. On NFS-managed lands, 10,684 acres burned at high soil burn severity, 58,784 acres burned at moderate soil burn severity, 70,201 acres burned at low soil burn severity and 30,642 acres remain unburned or burned at very low soil burn severity (Figure 1). The Chetco Bar fire burned area is characterized as steep, rugged terrain, with highly dissected slopes and narrow drainages. Dominant surficial geology is metamorphosed sedimentary and volcanic rocks, peridotite and other igneous rocks. Peridotite has been transformed into serpentine through a process known as serpentinization. This transformation is the result of hydration and metamorphic transformation of ultramafic (high iron and magnesium) rocks. -

Native American Paleontology: Extinct Animals in Rock Art

Peter Faris Native American Paleontology: Extinct Animals in Rock Art A perennial question in rock art is whether any help. Wolf ran round and round the raft of the animal imagery from North America por- with a ball of moss in his mouth. As he trays extinct animals that humans had observed ran the moss grew and earth formed on it. and hunted. A number of examples of rock art Then he put it down and they danced illustrating various creatures have been put around it singing powerful spells. The earth grew. It spread over the raft and forth as extinct animals but none have been ful- went on growing until it made the whole ly convincing. This question is revisited focus- world (Burland 1973:57). ing upon the giant beaver Castoroides. Based upon stylistic analysis and ethnology the author This eastern Cree creation tale is a version of suggests that the famous petroglyph Tsagaglalal the Earth Diver creation myth. The role played from The Dalles, Washington, represents Cas- by the giant beavers is a logical analogy of the toroides, the Giant Beaver. flooding of a meadow by beavers building their dams; and the description of the broad expanse GIANT BEAVERS of water surrounding the newly-created earth on its raft is a metaphor for a beaver’s lodge sur- The Trickster Wisagatcak built a dam of rounded by the water of the beaver pond. stakes across a creek in order to trap the The Cree were not alone in granting a promi- Giant Beaver when it swam out of its nent place in their mythology to the giant bea- lodge. -

EAFONSI Template

Environmental Assessment Chetco Bar Fire Salvage Project Fisheries and Aquatic Biota The following is a summary of the Aquatic Biota Biological Evaluation. The entire report is incorporated by reference and can be found in the project file, located at the RRSNF, Gold Beach Ranger District, Gold Beach, Oregon. Regulatory Framework In compliance with Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Forest Service Biological Evaluation (BE) process for Endangered, Threatened, Proposed or Sensitive fish species (Siskiyou LRMP S&G 4-2; page IV-27), the USDA Forest Service Region 6 Sensitive Species List (updated July 13, 2015) was reviewed and field reconnaissance was conducted in regard to potential effects on any of these species by actions associated with the Chetco Bar Area Salvage Project. Affected Environment The Action Area, as defined by the Endangered Species Act (ESA), is all areas to be affected directly or indirectly by the federal action and not merely the immediate area involved in the action [50 CFR § 402.02]. The Action Area not only includes the immediate footprint of the proposed salvage and road related activities, but any downstream reaches which may be affected indirectly. The ESA Action Area is also analyzed for Forest Service Sensitive Species. The proposed project is located within the Chetco River and Pistol River 5th field watersheds. All proposed project activities would occur within the South Fork Chetco River, Nook Creek, Eagle Creek, East Fork Pistol River-Pistol River, South Fork Pistol River, and North Fork Pistol River 6th field subwatersheds. All potential effects are also expected to occur within the boundaries of these subwatersheds. -

Final Report, Joint Fire Science Program, AFP 2004-2

Final report, Joint Fire Science Program, AFP 2004-2 Project Number: 04-2-1-95 Project Title: The influences of post-fire salvage logging on wildlife populations. Project Location: Davis Lake Fire, Deschutes National Forest in central Oregon Co-Principal Investigators: John P. Hayes and John Cissel. Contact Information: (541) 737-0946; [email protected] This final report details findings to date, and lists proposed and accomplished deliverables. Details on the study background, objectives, and methods are presented in the Annual Report of the Co-operative Forest Ecology Research (CFER) program (at http://www.fsl.orst.edu/cfer/research/pubs/06AnnualReport/pdfs/Manning.pdf) which can be considered a contribution to the final report. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS TO DATE Bird population responses • A total of 34 species of birds registered during two seasons of point counts. Of these, 15 species and one genus were abundant enough to warrant analysis. • Significant effects of salvage logging on bird abundance were demonstrated for 6 species. • For species whose abundances did differ, differences were probably related to effects on foraging and nesting habitat components. • Several species (brown creepers, yellow-rumped warblers, and 2 species of woodpeckers) were more abundant in unsalvaged stands. The western wood pewee also trended in that direction. While this response might be expected for woodpeckers and creepers which feed primarily on insects found in dead trees, and which nest in cavities of dead trees, the responses of warblers and pewees is harder to explain. • Species which feed and nest primarily on the ground, specifically the fox sparrow and the dark-eyed junco, were more abundant in salvaged stands. -

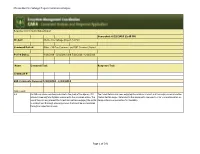

Chetco Bar Fire Salvage Project Comment Analysis Page 1 Of

Chetco Bar Fire Salvage Project Comment Analysis Response and Concern Status Report Generated: 6/22/2018 12:48 PM Project: Chetco Fire Salvage Project (53150) Comment Period: Other - 30-Day Comment and ESD Comment Period Period Dates: 4/16/2018 - 5/16/2018 and 5/18/2018 - 6/18/2018 Name Comment Text Response Text Comment # ESD Comments Received 5/18/2018 - 6/18/2018 Vaile, Joseph 1-2 An ESD may prove counterproductive to the goals of the agency, if it The Forest Service has been engaging the public in a robust and thorough process since the prevents meaningful mitigation measures to the proposed action. The Chetco Bar fire began. Refer also to the response to comment 1-1 for more information on use of the ESD may prevent the Forest Service from engaging the public design criteria and evaluation for feasibility. in a robust and thorough planning process that could be accomplished through an objection process. Page 1 of 341 Chetco Bar Fire Salvage Project Comment Analysis Name Comment Text Response Text 1-5 Please note that the discussion of the agency's desire for an ESD at page The EA states "An additional consideration is the health and safety of forest visitors and 2-6 of the Chetco Bar Fire Salvage EA makes reference to a concern for nearby private landowners due to numerous dead trees, as well as Forest Service staff and "the health and safety of forest visitors." We wholeheartedly agree that forest industry workers working in the Chetco Bar Fire Salvage project area. Traveling or this is a legitimate concern. -

Chetco Bar Fire Timber Salvage Project

United States Department of Interior Bureau of Land Management Coos Bay District Myrtlewood Field Office 1300 Airport Lane Coos Bay, OR 97459 Categorical Exclusion Review Chetco Bar Fire Timber Salvage Project DOI-BLM-ORWA-C040-2018-0002-CX BLM Office: Myrtlewood Field Office Lease/Serial/Case No. : DOI-BLM-ORWA-C040-2018-0002-CX Proposed Action Title: Chetco Bar Fire Timber Salvage Project Location of Proposed Action: Township 39 South, Range 13 West, Sections 1, 2, 11, 13-15, 22, 23, 25-27, Willamette Meridian, Curry County, Oregon (see attached Map2 and Map3). Background Reported on July 12, 2017, the Chetco Bar Fire started in the Kalmiopsis Wilderness on U.S. Forest Service Land from lightning strikes. The fire burned within the 2002 Biscuit Fire and 1987 Silver Fire scars between Brookings, Oregon to the west and Cave Junction to the east. Winds pushed the fire southward towards Brookings and onto private and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) administered lands in Curry County. The fire burned on approximately 185,920 acres of which 6,501 acres are BLM-administered lands. The fire burned on steep slopes (elevations range from 3,420 ft. on ridge tops to 1,200 ft. in drainages) within two watersheds (North Fork Chetco River and South Fork Pistol River). The BLM assigned a Burn Area Emergency Response (BAER) team to BLM-Administered land effected by the Chetco Bar Fire. The BAER team created a Burned Area Reflectance Classification (BARC) map and field reviewed the area to create a soil burn severity (SBS) map. SBS maps identifies fire-induced changes in soil and ground surface properties that may affect infiltration, run-off, and erosion potential (Parsons et al. -

Lt. Aemilius Simpson's Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826

The Journal of the Hakluyt Society August 2014 Lt. Aemilius Simpson’s Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826 Edited by William Barr1 and Larry Green CONTENTS PREFACE The journal 2 Editorial practices 3 INTRODUCTION The man, the project, its background and its implementation 4 JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE ACROSS THE CONTINENT OF NORTH AMERICA IN 1826 York Factory to Norway House 11 Norway House to Carlton House 19 Carlton House to Fort Edmonton 27 Fort Edmonton to Boat Encampment, Columbia River 42 Boat Encampment to Fort Vancouver 62 AFTERWORD Aemilius Simpson and the Northwest coast 1826–1831 81 APPENDIX I Biographical sketches 90 APPENDIX II Table of distances in statute miles from York Factory 100 BIBLIOGRAPHY 101 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Fig. 1. George Simpson, 1857 3 Fig. 2. York Factory 1853 4 Fig. 3. Artist’s impression of George Simpson, approaching a post in his personal North canoe 5 Fig. 4. Fort Vancouver ca.1854 78 LIST OF MAPS Map 1. York Factory to the Forks of the Saskatchewan River 7 Map 2. Carlton House to Boat Encampment 27 Map 3. Jasper to Fort Vancouver 65 1 Senior Research Associate, Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary, Calgary AB T2N 1N4 Canada. 2 PREFACE The Journal The journal presented here2 is transcribed from the original manuscript written in Aemilius Simpson’s hand. It is fifty folios in length in a bound volume of ninety folios, the final forty folios being blank. Each page measures 12.8 inches by seven inches and is lined with thirty- five faint, horizontal blue-grey lines. -

Taming the Wild – Understanding Risks and Responses to Water Supplies from Wildfires

TAMING THE WILD – UNDERSTANDING RISKS AND RESPONSES TO WATER SUPPLIES FROM WILDFIRES Glen Leverich 1 Rodrigo Prugue 2 2 0 19 P N WS - AWWA Conference, Vancouver, WA May 3, 2019 1 2 OUTLINE OF TALK Photo of City of Brookings, OR (courtesy of City of Brookings) OVERVIEW OF WILDFIRE ACTIVITY AND RISKS IN THE NORTHWEST Photo of Chetco Bar Fire (courtesy of USFS) Spatial frequency of recorded burn events in OR and WA: 1908–2017 Annual total acres burned in OR and WA: 1908–2018 Vancouver Chetco R. Source data: BLM, 2017 Source data: BLM, 2018 GIS analysis: Stillwater, 2018 Analysis: Stillwater, 2019 Conceptualization of sediment yield and associated vegetation and litter recovery • Wildfires can lead to during the fire-induced “window of accelerated rates of runoff disturbance” and erosion Increasing vegetation cover • Exposed, burned soils influence of erosion-limiting during storms are more factors litter cover susceptible to mass wasting and sediment- fire-induced sediment laden runoff—the Fire- yield Flood-Erosion sequence ‘background’ (Neary et al., 2005, USDA) E R I F sediment yield • “Window of disturbance” S E D I M E N T Y I E L D occurs for months to years window of disturbance until natural system T I M E recovers (Prosser and Adapted from Shakesby and Doerr, 2006, Williams, 1998, Hyd. Proc.) Earth Sci. Rev. Photo of burned area of Chetco watershed (Stillwater Sciences) Photo of Montecito Debris flows following Thomas Fire in Santa Barbara County, CA, Jan 2018 (photo courtesy of Scripps Institute) WILDFIRE EFFECTS TO DRINKING WATER SUPPLY Photo of burned area of Chetco watershed (Stillwater Sciences) WILDFIRE EFFECTS TO DRINKING WATER SUPPLY •Two-thirds of freshwater resources in the U.S. -

Life History Account for Siskiyou Chipmunk

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group SISKIYOU CHIPMUNK Tamias siskiyou Family: SCIURIDAE Order: RODENTIA Class: MAMMALIA M058 Written by: C. Polite, T. Harvey Reviewed by: M. White Edited by: M. White DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE AND SEASONALITY Locally common, permanent resident of mixed conifer, redwood, and Douglas-fir forests from sea level to 2000 m (0-6562 ft) in the northwestern region of the Klamath and North Coast Ranges (Johnson 1943). SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Herbivorous; forages principally on log-strewn forest floors and into adjacent chaparral; climbs freely on trunks and lower branches of large trees (Johnson 1943). Food habits of T. siskiyou unknown, but the closely related T. senex feeds on fungi and seeds of forbs, shrubs, and conifers. Cover: Uses brush, logs, stumps, snags, thickets, rock piles, and burrows as cover. Reproduction: Lines burrows with dry grass and moss. Also uses tree nests while raising young. Water: No data found. Pattern: Uses conifer forests, especially in mature, open stands with shrubs and large-diameter logs, stumps, and snags available. SPECIES LIFE HISTORY Activity Patterns: Diurnal activity. May become torpid during winter months. Seasonal Movements/Migration: Not migratory Home Range: In Washington, home ranges of T. townsendii females overlapped very little, suggesting exclusive use (Meredith 1972). In Oregon, home ranges varied from 0.5-1.0 ha (1.25-2.47 ac) (Gashwiler 1965). Territory: No data found; probably same as home range (Meredith 1972). Reproduction: Breeds from April to July; most births occur in May. One litter/yr of 4-5 young (range 3-6). -

Forest Health Highlights in Oregon 2017

Forest Health Highlights in Oregon 2017 DRAFT Oregon Department of Pacific Northwest Region Forestry Forest Health Protection Forest Health Program for the greatest good AGENDA ITEM 4 Attachment 2 Page 1 of 36 Forest Health Highlights in Oregon 2017 Joint publication contributors: Christine Buhl¹ Zack Heath² Sarah Navarro¹ Karen Ripley² Danny Norlander¹ Robert Schroeter² Wyatt Williams¹ Ben Smith² ¹Oregon Department of Forestry ²U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer, and lender Cooperative Aerial Survey: 2017 Flight lines DRAFT The aerial survey program is changing! Give us input to better serve your needs. Front cover image: Orange hawkweed (Hieracium aurantiacum), a European exotic, was first identified in Oregon in 2017 in Clatsop County (Photo by Peter Dziuk). AGENDA ITEM 4 Attachment 2 Page 2 of 36 Table of Contents SUMMARY .........................................................................................................................................1 AERIAL AND GROUND SURVEYS .........................................................................................................2 ABIOTIC STRESSORS ...........................................................................................................................4 Climate and Weather ...................................................................................................................4 Drought .......................................................................................................................................5 -

Final Rogue Fall Chinook Salmon Conservation Plan

CONSERVATION PLAN FOR FALL CHINOOK SALMON IN THE ROGUE SPECIES MANAGEMENT UNIT Adopted by the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission January 11, 2013 Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife 3406 Cherry Avenue NE Salem, OR 97303 Rogue Fall Chinook Salmon Conservation Plan - January 11, 2013 Table of Contents Page FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 6 RELATIONSHIP TO OTHER NATIVE FISH CONSERVATION PLANS ................................. 7 CONSTRAINTS ............................................................................................................................. 7 SPECIES MANAGEMENT UNIT AND CONSTITUENT POPULATIONS ............................... 7 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................... 10 Historical Context ......................................................................................................................... 10 General Aspects of Life History .................................................................................................... 14 General Aspects of the Fisheries .................................................................................................. -

Mammal Watching in the Pacific Northwest, Summer 2019 with Notes on Birding, Locations, Sounds, and Chasing Chipmunks

Mammal watching in the Pacific Northwest, summer 2019 With notes on birding, locations, sounds, and chasing chipmunks Keywords: Sciuridae, trip report, mammals, birds, summer, July Daan Drukker 1 How to use this report For this report I’ve chosen not to do the classic chronological order, but instead, I’ve treated every mammal species I’ve seen in individual headers and added some charismatic species that I’ve missed. Further down I’ve made a list of hotspot birding areas that I’ve visited where the most interesting bird species that I’ve seen are treated. If you are visiting the Pacific Northwest, you’ll find information on where to look for mammals in this report and some additional info on taxonomy and identification. I’ve written it with a European perspective, but that shouldn’t be an issue. Birds are treated in detail for Mount Rainier and the Monterey area, including the California Condors of Big Sur. For other areas, I’ve mentioned the birds, but there must be other reports for more details. I did a non-hardcore type of birding, just looking at everything I came across and learning the North American species a bit, but not twitching everything that was remotely possible. That will be for another time. Every observation I made can be found on Observation.org, where the exact date, location and in some cases evidence photos and sound recordings are combined. These observations are revised by local admins, and if you see an alleged mistake, you can let the observer and admin know by clicking on one of the “Contact” options in the upper right panel.