My Old Man David Gates and His Group Bread Recorded a Hit Song in 1974 Called

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cash Box,- Insight&Sound

cash box,- insight&sound David Gates: Flying Solo, Flying High AI Martino: Opening The 'Door Of The Sun,' Again When Bread disbanded in 1973, few groups on the contemporary music scene had Just back from an extended engagement at Puerto Rico's El San Juan Hotel, sun- claimed as much notoriety or success as had the foursome. The group, original David tanned and zestful Al Martino doesn't look at all like he's had a hard climb to the top. Gates, Jim Griffin, Robb Royer (later Larry Knechtel) and Mike Botts, recorded six But his career has come a long way from a first prize on the Arthur Godfrey Talent albums for Elektra from late 1969 to their dissolution, each containing singles that Scouts Show, launching pad for a number of today's stars. From then on it hasn't been were to become easily recognizable as stemming from the compositional genius of an easy one for this Philadelphia born Italian crooner. It began in 1952 with the re- Gates himself. In fact, nearly all Bread's of phenomenal chart and sales success were lease of his Godfrey winning tune, "Here In My Heart." The song shot over the million penned by Gates, songs that have been re -arranged and performed by artists like mark in sales and as Martino looks back it he on says, "It was too much too soon. I Peggy Lee, Sinatra, and recently Telly Savalas! Such widespread acceptance by both simply wasn't ready for the demands of instant success." the performing and consuming communities are in large part due to Gates' back- Fora time he tried to enter the construction business in California but, after his un- ground and philosophy towards his music. -

Lake Union Herald (ISSN 0194- 908X) Is Published Monthly by the Lake If I Had All the Options Before Me (And I Do), Then I Think I Would Want My Union Conference, P.O

0 the OCTOBER 1998 Reaching the Inaccessible Mission Aviation CONTENTS EDITOR I A L 2 Editorial: I'm Writing My Obituary 3 Operation Amigo: Snyders I'm Writing My 0 Honored Obituary 4 New Members 5 Reaching the Inaccessible with BY DON SCHNEIDER, LAKE UNION Mission Aviation CONFERENCE PRESIDENT 10 Who's Caring for the Caregiver? 4 12 Hinsdale Center for Repro- oday I'm writing my obituary. I worked on it yesterday—and last week. I plan duction Gives Nature a T to edit it a bit tomorrow, too. I'm preparing it to be read by a lot of people. Helping Hand Possibly it will be read at my funeral, although I'm not sure exactly when that will 14 Rebuilding Hope be. I certainly don't plan for that event to come any time soon; but when it does, 15 Exploring God's World: someone will surely read some kind of an obituary. I want it to be a good one, and The Ways of the Ant I'd like to have some input on what it says. 0 16 Andrews University News An obituary is like a summary statement. A lot of things get left out, and a 17 Education News short statement— sometimes just a word or two—is made that says a lot about a 18 Youth News person's life. We all use life summaries. We talk about Peter, always quick to speak 19 Local Church News (but not necessarily the right things); George Washington, the father of our 22 World Church News country; or Columbus, who discovered America. -

FR. KEVIN DILLON's HOMILY DATED 26.07.2020 I Just Had an Ideas And

FR. KEVIN DILLON’S HOMILY DATED 26.07.2020 I just had an ideas and I shouldn’t announce ideas on YouTube because someone else will steal it but I thought maybe, maybe we should there’s still a lot of priests saying mass all over the world, may be should have masks in liturgical colours so I should have a green one now and a white one Christmas and Easter and a purple one for Advent and Lent and a red one for the Feast of the Martyrs and the Apostles. Now, don’t tell anyone I just had that idea but that might be a marketing opportunity for someone, so let’s see what happens with that. On another note – question for you, have a think, what is the most beautiful song ever written? Now that’s probably pretty hard because there’s lots of songs around. But if I was to make a list there’s one song that would definitely be on it and it was in my mind during the week because I received a card from a granddaughter of a lady whose funeral I conducted a couple of weeks back and when I had met with the family, they were searching around for music to put behind the photos. At that stage I think that we were still able to have 50 people at the funeral and anyhow, the song is one which I have suggested a few times for use at funerals in similar circumstances behind photos or special reflection and it is for me one of the most beautiful songs ever written. -

Steve Ripley a Rock and Roll Legend in Our Own Backyard Who Has Worked with Some of the Greats

Steve Ripley A rock and roll legend in our own backyard who has worked with some of the greats. Chapter 01 – 1:16 Introduction Announcer: Steve Ripley grew up in Oklahoma, graduating from Glencoe High School and Oklahoma State University. He went on to become a recording artist, record producer, song writer, studio engineer, guitarist, and inventor. Steve worked with Bob Dylan playing guitar on The Shot of Love album and on The Shot of Love tour. Dylan listed Ripley as one of the good guitarist he had played with. Red Dirt was first used by Steve Ripley’s band Moses when the group chose the label name Red Dirt Records. Steve founded Ripley Guitars in Burbank, California, creating guitars for musicians like Jimmy Buffet, J. J. Cale, and Eddie Van Halen. In 1987, Steve moved to Tulsa to buy Leon Russell’s recording facility, The Church Studio. Steve formed the country band The Tractors and was the cowriter of the country hit “Baby Like to Rock It.” Under his own record label Boy Rocking Records, Steve produced such artists as The Tractors, Leon Russell, and the Red Dirt Rangers. Steve Ripley was sixty-nine when he died January 3, 2019. But you can listen to Steve talk about his family story, his introduction to music, his relationship with Bob Dylan, dining with the Beatles, and his friendship with Leon Russell. The last five chapters he wanted you to hear only after his death. Listen now, on VoicesofOklahoma.com. Chapter 02 – 3:47 Land Run with Fred John Erling: Today’s date is December 12, 2017. -

Boyzone Full Album

1 / 2 Boyzone Full Album KOLEKSI LAGU BOYZONE FULL ALBUM NONSTOP MP3 3GP MP4 HD Free Download, KOLEKSI LAGU BOYZONE FULL ALBUM NONSTOP Online Play and .... Boyzone Greatest Hits - The Best Of Boyzone Full Album 2020. Uploader: Beautiful Love Songs; Duration: 1:29:44; Default Size: 126.19 MB; Default Bitrate: 192 .... The Best Of Westlife Westlife Greatest Hits Full Album mp3. ... Piano, Vocal & Guitar by Boyzone in the range of E4-B5 from Sheet Music Direct.. Boyzone Full Album MP3 Download, Video 3gp & mp4. List download link Lagu MP3 Boyzone Full Album gratis and free streaming terbaru hanya di Stafaband.. Boyzone's amazing cover version of "Everything I Own" from their new album BZ20. (C) 2013 Warner/Rhino Lyrics: David Gates Performers: Boyzone.. To support music producers, buy Boyzone Greatest Hits - The Best Of Boyzone (full album) and Original tapes in the Nearest Stores and iTunes .... Selena has her first top 10 | Top Latin Albums (see ge 58) since January 2003 ... 2 on the Official Charts Co. albums tally behind Boyzone's “Brother” (see page 59). ... Mass Chain traditional Merchant Go to www.billboard.biz for complete chart ... Music Forever. Music Forever. Subscribe. Boyzone Greatest Hits Full Album - Boyzone Best Songs 2018. Show less Show more .... Wonder World (released November 7, '11) is the group's sophomore album and their first full length album release after their moderately .... Download song Boyzone Greatest Hits || The Best Of Boyzone full album 2020 MP3 you can download it for free at Mp3 Soul. Song details .... Ireland's answer to the Backstreet Boys was one of Europe's most popular boy bands through the late 1990s. -

Take Me Now Bread

www.acordesweb.com Take Me Now Bread this is my second time in submitting a tab this song is take me now by the band bread>>>>>> David Gates in late 60s hope you enjoy this song its a very sentimental. for any comments just email me at [email protected] bread: take me now david gates I started it with F...but u can use the C chords if you now how to transpose it. Verse: F I need Bb Baby I need your love right now C7 And I want F Baby I want to show you how Dm Come on G Encuentra muchas canciones para tocar en Acordesweb.com www.acordesweb.com You know that we've waited long enough C And now it's time Bb C7 Time to be lovers F So I try Bb Try to be all you want me to C7 And it's hard F But baby it's worth it all for you Dm And it hurts G Making me wait for you this way C I can't go on Bb So come on C7 F And take me now Encuentra muchas canciones para tocar en Acordesweb.com www.acordesweb.com (chorus) Bb Take my love C Bb F Make come true the feelings I've been dreaming of C7 F Take me now Bb Take me fast C You can trust in me Bb F Our love will ever last 2nd Verse: F I know Bb We haven't known each other long C7 But still F Something so right just can't be wrong Dm G Encuentra muchas canciones para tocar en Acordesweb.com www.acordesweb.com Besides it ought to be up to me and you C When it's time Bb C7 Time for each other F I live Bb Live for the days we live as one C7 Look back F Back over all the things we've done Dm But now G Baby I need your love right now C I can't go on Bb So come on C7 F And take me now Encuentra muchas canciones para tocar en Acordesweb.com www.acordesweb.com (chorus) Bb Take my love C Bb F Make come true the feelings I've been dreaming of C7 F Take me now Bb Take me fast C You can trust in me Bb F Our love will ever last End...its up to you if how many times you want to repeat the chorus to end it up...thanks hope you enjoy it. -

Bread: Just Like You Remember Them When the Group Disbanded They Were 'Lost Without Your Love; So They Reunited to Produce an Album by the Same Name

Portfolio March 14, 1977 Retriever Pa ge 8 Bread: Just Like You Remember Them When the group disbanded they were 'Lost Without Your Love; so they reunited to produce an album by the same name. By Glenn Isaacson When Bread disbanded late in 1973, they said they were taking a sabbatical from their work as a group. They would us~ the time to branch out into individual dIrec tions and to experiment with solo projects. They said it was a temporary measure and they would reunite someday. One year went by ; then two. David Gates put out two moderately successful solo albums and a couple of hit singles. James Griffin put out a solo album that flopped. Three years went by. Larry Knechtel played studio piano on dozens. of albums for dozens of artists. It seemed lIke every third studio album released Knichtel had played on it. Mike Botts played drums on Linda Rondstadt's tour. By then, even the staunchest Bread fans gave up hope of the group ever getting back together. But late in 1976 the announcement came Bread was to reunity, with all the same members. A single would be out within a month and an album to follow soon after. The ' single was " Lost Without Your Love". It was a pretty, soft rock ballad perfectly cast in the mold of the Bread sound we all knew and loved. "Bread is back," it seemed to say, "just like you remember them." I am sure the song worked its magic on new listeners not familiar with the old Bread material. -

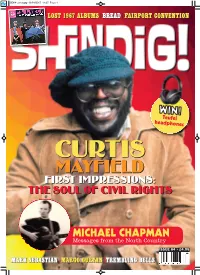

SHINDIG! Article (Click Here)

SD64 cover.qxp 06/01/2017 11:07 Page 1 LOST 1967 ALBUMS | BREADBREAD | FAIRPORTFAIRPORT CONVENTIONCONVENTION WIN! Teufel headphones CURTISCURTIS MAYFIELDMAYFIELD FIRSTFIRST IMPRESSIONS:IMPRESSIONS: THETHE SOULSOUL OFOF CIVILCIVIL RIGHTSRIGHTS MICHAEL CHAPMAN Messages from the North Country ISSUE 64 • £4.95 MARKMARK SEBASTIANSEBASTIAN | MARGOMARGO GURYANGURYAN|TREMBLINGTREMBLING BELLSBELLS SD64 Contents.qxp 13/01/2017 13:51 Page 1 welcomecontents Issue 64 February 2017 64 Howdy Shindiggers! It’s taken a long time coming. Curtis Mayfield, believe it or not, is Features our first black cover star. Why it’s taken so long I don’t know. Laurie Styvers We’ve had insets of Sly & The Family Stone and Betty Davis, but US psych-folkie makes good in England Curtis is our first full cover. And deservedly so. 22 Shindig! is a magazine that can happily accommodate all manner Terry Dolan of garage, psych and progressive music, but also adores the lesser The remarkable story behind a lost classic celebrated areas of good old pop music and of course the majesties 26 offered to us from black musicians, whether R&B, soul, funk or 1967 at 33rpm the myriad hybrids that crossed over in the early ’70s. Once again, 40 of the year’s essential overlooked long-players 40 Kris Needs delivers another of his epic histories. Part One of his Curtis Mayfield story focuses on the Chicago legend’s early years. Mark Sebastian Next issue we’ll pick up the story with the second half of his ‘Summer In The City’ co-writer and brother of John 48 career: the almighty solo years. -

Rock and Roll Hall of Famer, Leon Russell, Was Born Claude Russell

Rock and Roll Hall of Famer, Leon Russell, was born Claude Russell Bridges on April 2, 1942 in Lawton, Oklahoma and died November 13, 2016 at his home in Hermitage, TN. A birth inJury to his vertebrae caused a slight paralysis on his right side that would shape his distinct musical style. His family moved upstate to Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1953, where within a few years he began to play with various local bands and develop his musical skills that would eventually make him an in-demand session player in Hollywood and eventual rock and roll superstar. In 1960, Russell made the trek from Oklahoma to Los Angeles to try and make it in the thriving music business. Too young to Join the musician’s union which was required to play the union recording sessions, Russell worked the clubs up and down Los Angeles, along with Tulsa bandmates David Gates, who later formed the group Bread, and drummer Chuck Blackwell. On occasion the three would play live shows on the weekends with various recording artists, including an occasional gig with Country Music Hall of Famer George Morgan, father of country music singer Lorrie Morgan. Russell eventually got into the local musician’s union, where as a Hollywood session player Russell played on dozens of hit records, including “Monster Mash” by Bobby Pickett, “Mr. Tambourine Man” by The Byrds, “Surf City” by Jan & Dean, “Birds & The Bees” by Jewel Akens, “Day After Day” by Badfinger, “Help Me Rhonda” by The Beach Boys, “This Diamond Ring” by Gary Lewis & The Playboys, “Danke Schoen” by Wayne Newton, “A Taste of Honey” by Herb Alpert, and scores of others. -

2---THE ONLY INTERVIEW I've DONE by Fax

Leon Russell: Feb. 7, 1992---THE ONLY INTERVIEW I'VE DONE BY Fax.... He is a stranger in a strange land. An enduring architect of American pop music, Leon Russell is also a notoriously reserved star. The last time he played Biddy Mulligan's the encore was so emotional that Russell scooted off stage straight into his tour bus. And when I wanted to ask Russell about his contributions to contemporary music - as a session player for Phil Spector, sideman and songwriter for Gary Lewis and the Playboys, and recent collaborator with Bruce Hornsby - I had to fax questions to his Nashville studio. "I require a short time to think about replies to strangers and sometimes am nervous around strangers," Russell faxed back. He'll appear solo, surrounded by several million dollars of sound gear, at 10:30 tonight at Biddy Mulligan's, 7644 N. Sheridan. Expect new things as well as Russell's hits - "Tight Rope," "This Masquerade" (popularized by George Benson) and perhaps "Superstar" - which Russell cowrote with Bonnie Bramlett and is currently being covered in concert by Luther Vandross. The gravelly voiced Russell is cut from the same veiled cloth as J. J. Cale, another reclusive Oklahoman. Russell was born 50 years ago this April in Lawton, Okla. Both his parents played the piano, and Leon learned music when he was very young. He grew up fast, forming his first band at age 14. Russell played trumpet. "Oklahoma enjoyed a perfect environment for the growth of musical artists, in the respect that liquor by the drink was illegal at that time . -

A Response to David Gates: “The Door Is About to Close Are You Ready?” by Pastor Stephen Bohr

A Response to David Gates: “The Door is About to Close Are You Ready?” by Pastor Stephen Bohr A recent internet message by David Gates has caused quite a sensation among many in the Seventh-day Adventist Church. At Secrets Unsealed, we have received numerous emails, text messages and phone calls asking what we think of his message. In addition, as I have traveled, many have sought my personal opinion of his remarks. What I think is not important. What is important is whether his message squares with the Bible and the Spirit of Prophecy. Before I respond to David’s complex prophetic scenario, I would like to make something clear. I respect David’s unreserved commitment to the Lord’s cause. He has made huge personal and family sacrifices to carry forward the work of GMI. He has inspired scores of youth to enter mission service. He travels tirelessly pursuing broadcast opportunities for present truth. I share David’s longing for revival and reformation in the church—it is a dire need. No one can question David’s commitment to the Lord, his sincerity and His longing passion for the coming of Jesus. I have spent quality time with David. I have traveled on his plane, roomed with him at a youth event in Panama where one evening in the midst of a torrential rainstorm, we discussed Revelation’s seven seals for over three hours. My response to David’s message as follows in no way questions his love for the Lord, his personal integrity or his sincerity. Areas of Agreement I agree with the intention of David’s message. -

David Gates "Converging Crises" Review F

David Gates "Converging Crises" review F David Gates is one of my personal heroes of faith and action ever since i learned about him from the book “Mission Pilot” which i was handed to read in Cambodia in 2006. Many of his sermons have inspired me and strengthened my faith and prodded me to do more for my Master. In August 2007 in Bangkok, he was a speaker at the ASI convention which i attended. His dynamism was contagious, and he really exemplified the pattern of Jesus – giving your all to save souls. He did make a few comments which concerned me – comments denigrating the leaders of the United States government, and a few odd conspiracy theories. I politely warned him about this in a couple of emails, to which there has never been a reply. I hadn’t listened to any of his sermons for about half a year, when, in October i think, i noticed that there was some bruha on audioverse.org about the removal of his “Converging Crisis” audio. Reading the reasons given, and knowing Brother David’s conspiracy comments before, i sent a email encouraging the webmaster at audioverse. But actually, i should have carefully listened to the content first before doing that. What has prompted this review, is that last week a strong SDA friend in India said two of his closest church Brothers had stopped attending church because of this sermon, saying that “Jesus is going to come back before 2031 anyway, so what need is there to go to church now”? Fortunately my friend did not follow them.