The K-9 'Nose'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Setter Association of America

The English Setter Association of America Judges’ Education Presentation The first dog registered with the AKC was an English Setter named ADONNIS Champion Rock Falls Colonel Retired from the show ring in 1955 and was the first dog in the history of the AKC to have won 100 Best in Shows. Did You Know? The first AKC-licensed pointing-breeds field trial was conducted by the English Setter Club of America in 1924 in Medford, NJ. Original Purpose & History of the English Setter The English Setter is one of the oldest breeds of gun dog with a history dating back to the 14th century. It was thought to be developed between crosses of Spanish Pointer, Water Spaniel and the Springer Spaniel. Its purpose was to point, flush and retrieve upland game birds. The modern English Setter owes its appearance to Mr. EDWARD LAVERACK, who developed his own strain of the breed by careful inbreeding during the 19th century. Another Englishman, Mr. R. PURCELL LLEWELLIN began a second strain based upon Laverack’s line that developed into the working setter. Today you will hear the term Llewellin Setter. This is not a separate breed, just a different type, more often referred to as the Field Setter. This strain is more often used in field trials. ▪Although the Llewellin English Setter is still the predominate type seen in the field today, Laverack English Setters are making their mark. ▪The first Dual Champion finished in 1985. ▪There are 13 Dual Champions to date. ▪Numerous show English Setters have earned hunting titles. ▪You will see whiskers left on. -

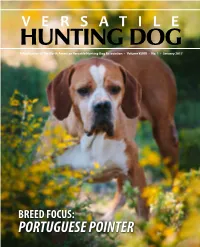

V E R S a T I L E Portuguese Pointer

VERSATILE HUNTING DOG A Publication of The North American Versatile Hunting Dog Association • Volume XLVIII • No. 1 • January 2017 BREED FOCUS: PORTUGUESE POINTER IF SOMEONE TOLD YOU THAT OF THE TOP 100* SPORTING DOGS EAT THE SAME BRAND OF FOOD Would you ask what it is? HELPS OPTIMIZE 30% PROTEIN / SUPPORTS HELPS KEEP OXYGEN METABOLISM 20% FAT IMMUNE SKIN & COAT FOR INCREASED HELPS MAINTAIN SYSTEM IN EXCELLENT ENDURANCE LEAN MUSCLE HEALTH CONDITION proplansport.com SOLD EXCLUSIVELY AT PET SPECIALTY RETAILERS *Based on National, World, Regional and Species Championship Winners during the 12-month period ending December 31, 2015. The handler or owner of these champions may have received Pro Plan dog food as Purina ambassadors. Purina trademarks are owned by Société des Produits Nestlé S.A. Any other marks are property of their respective owners. Printed in USA. VERSATILE HUNTING DOG Volume XLVIII • No. 1 • January 2017 NAVHDA International Officers & Directors David A. Trahan President Bob Hauser Vice President Steve J. Greger Secretary Richard Holt Treasurer Chip Bonde Director of Judge Development Jason Wade Director of Promotions FEATURES Tim Clark Director of Testing Tim Otto Director of Publications Steve Brodeur Registrar 4 Breed Focus: Portuguese Pointer • by Craig Koshyk James Applegate Director of Information Resources Tracey Nelson Invitational Director Marilyn Vetter Past President 14 All About Our Youth! • by Chris Mokler Versatile Hunting Dog by Brad Varney Publication Staff 18 The Last Shot • Mary K. Burpee Editor/Publisher Erin Kossan Copy Editor Sandra Downey Copy Editor Rachael McAden Copy Editor Patti Carter Contributing Editor Dr. Lisa Boyer Contributing Editor Nancy Anisfield Contributing Editor/Photographer 4 Philippe Roca Contributing Editor/Photographer Dennis Normile Food Editor Maria Bondi Advertising Coordinator David Nordquist Webmaster Advertising Information DEPARTMENTS Copy deadline: 45 days prior to the month of President’s Message • 2 publication. -

Hunting Style of the Poodle the Poodle Historically Was a Versatile

Hunting Style of the Poodle The Poodle historically was a versatile hunting dog, developed pre-firearms, originally to ‘spring’(flush) game birds and small game in the Medieval era for nobleman’s falcons. Currently the Poodle is a versatile, all-purpose hunting dog, adept at finding and retrieving upland game birds and retrieving waterfowl. Training and field experience can affect the degree to which a Poodle exhibits the hunting style described below. The following is an overview of the typical characteristics shown by both Standard and Miniature Poodles while hunting upland game. The Poodle covers ground efficiently and at a moderately quick pace maintaining its endurance throughout a day in the field. Some Poodles will occasionally employ a bouncing technique, particularly in high, dense cover. The Poodle possesses an excellent nose, hearing, drive and intelligence. He will use all of these attributes, plus ground and air scent, to find and flush game. The poodle will generally maintain a reasonable working distance, quartering gun to gun if trained to do so, although windshield wiper-like quartering may not be typical, it will focus on those areas that are more likely to hold birds, showing no reluctance to enter even the densest cover. After finding game, the Poodle may slow as it attempts to locate the bird using scent, sight and hearing. A determined drive toward the bird then completes the flush. Both hard and softer flushes are equally acceptable. The athleticism of the Poodle will often enable it to catch the flushed bird. The Poodle should show no reluctance to retrieve to the handler from either land or water. -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Dog Breed Characteristics & Behavior

Behavior & Training 415.506.6280 Available B&T Services Dog Breed Characteristics & Behavior Why is it important to know about the characteristics and behavior of different breeds? All dogs are individuals and have their own personalities. At the same time, different breeds tend to also have certain characteristics that help define that particular breed. This information can be helpful to you when you are choosing a dog or trying to understand his behavior. The AKC (American Kennel Club) places dog breeds within seven different groups. In order to account for the different behaviors within a particular group, some groups can be further subdivided into families. Herding group: Breeds in this group were bred to herd sheep and cattle. They do this by stalking and staring, barking and/or nipping at their charges. They are bred to be intelligent, athletic and diligent and they are very trainable. Dogs from this group will do best with lots of exercise. They do even better if they have a job such as agility where they can use their natural athletic ability to navigate an agility course. Barking can be a problem if they are bored and they may attempt to “herd” their people-pack by nipping and chasing. Characteristics: Herding breeds: Alert Collies Smart Sheepdogs Independent Cattle dogs Confident Corgis Trainable Shepherds Loyal Belgian Malinois Affectionate Belgian Tervuren 171 Bel Marin Keys Blvd., Novato, CA 94949 Dog Breed Characteristics & Behavior Like us at: Page 1 of 7 Behavior & Training 415.506.6280 Available B&T Services Hound group: Hounds were originally bred to hunt. -

FINNISH HOUND Native Breed of FINLAND - SUOMENAJOKOIRA (FCI General Committee, Helsinki, October 2013)

FINNISH HOUND Native breed of FINLAND - SUOMENAJOKOIRA (FCI General Committee, Helsinki, October 2013) (FCI Show Judges Commission, Cartagena, February 2013) FINNISH HOUND – suomenajokoira FCI Group 6 Section 1.2 Breed number 51 Date of publication of the official valid standard 17/07/1997. Official breed club in Finland, Finnish Hound Association – Suomen Ajokoirajärjestö - Finska Stövarklubben ry versio b//SAJ/ Auli Haapiainen-Liikanen 24.12.2014 proved History of the breed In Finland in the beginning of 19th century there were in addition to the Finnish country dogs also many dogs resembling the European hound breeds.The systematic development of the Finnish Hound breed can be said to have begun when hunting enthusiasts established Suomen Kennelklubi, a precursor of the Finnish Kennel Club, in 1889. One of their first desires was the development of a hound-type breed for Finnish conditions. As the breeds introduced to our country from abroad, primarily Russia, Sweden and England, did not meet the requirements of the Finnish hunting community, a group of active hunters began to search the existing Finnish dog population for individuals with the best hunting traits. The aim was to breed a native hound-type dog from them. The first standard was written in 1932. The breeding associations in different parts of the country were very important to the development of the breed. Three dogs were selected from the first dog show arranged by Suomen Kennelklubi and eight more were added the next year. The first breed characteristics were determined on the basis of these dogs in 1893. Reddish brown was confirmed as the approved colour. -

Live Weight and Some Morphological Characteristics of Turkish Tazi (Sighthound) Raised in Province of Konya in Turkey

Yilmaz et al. 2012/J. Livestock Sci. 3, 98-103 Live weight and some morphological characteristics of Turkish Tazi (Sighthound) raised in Province of Konya in Turkey Orhan Yilmaz1, Fusun Coskun2, Mehmet Ertugrul3 1Igdir University, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Animal Science, 76100, Igdir. 2Ahi Evran University, Vocational School, Department of Vetetable and Livestock Production, 40000, Ankara. 2Ankara University, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Animal Science, 06110, Ankara. 1Corresponding author: [email protected] Office: +90-4762261314/1225, Fax: +90-4762261251 Journal of Livestock Science (ISSN online 2277-6214) 3:98-103 Abstract This study was carried out to determine the distributions of body coat colour and the body measurements of the Turkish Tazi (Sighthound) raised in province of Konya by comparing with some other Sighthound breeds from different regions of Turkey and UK. To this end, a total of 41 (18 male and 23 female) Tazi dogs was analyzed with the Minitab 16 statistical software program using ANOVA and Student’s t-Test. Descriptive statistics for live weight 18.4±0.31, withers height 62.0±0.44, height at rump 62.1±0.50, body length 60.7±0.55, heart girth circumference 63.9±0.64, chest depth 23.1±0.21, abdomen depth 13.9±0.21, chest width 17.4±0.25, haunch width 16.4±0.18, thigh width 22.3±0.26, tail length 45.7±0.37, limb length 38.9±0.31, cannon circumference 10.2±0.11, head length 24.0±0.36 and ear length 12.8±0.19 cm respectively. -

Pet Care of a Dog

Pet Care of a Dog Dogs are hugely popular pets. In fact, there are eight and a half million dogs being kept as pets in the UK alone. They are known as ‘man’s best friend’, but how should dogs be cared for and what do we actually know about them? Diet Dogs are omnivores, which means they need a well-balanced diet of meat and plant-based foods. They need one meal a day, unless the vet advises otherwise. Their teeth are well-developed, with sharp incisors for tearing meat, and molars for grinding plant foods. They must have access to clean, fresh water at all times, or else they are at risk of becoming very poorly. Environment Dogs need a comfortable, draught-free, clean and quiet environment. They need to be able to sleep, undisturbed. There needs to be access for them to go outside to the toilet regularly, and have some form of exercise appropriate for their breed, every day. Did You Know? After all, compare the type of walk a St Bernard The common ancestor needs compared to a dachshund! of dogs is the wolf! Dogs need a place where they can go if they are frightened. Dogs have very varied temperaments, or might have been previously mistreated, which means some scare more easily than others. Page 1 of 3 Pet Care of a Dog Dog behaviour Dogs are intelligent, playful animals, who need to have suitable toys or objects to play with, along with regular exercise. There are 400 different breeds of dog, and each breed has different traits suitable for the purpose of its breed. -

Sporting Group Study Guide Naturally Active and Alert, Sporting Dogs Make Likeable, Well-Rounded Companions

Sporting Group Study Guide Naturally active and alert, Sporting dogs make likeable, well-rounded companions. Remarkable for their instincts in water and woods, many of these breeds actively continue to participate in hunting and other field activities. Potential owners of Sporting dogs need to realize that most require regular, invigorating exercise. The breeds of the AKC Sporting Group were all developed to assist hunters of feathered game. These “sporting dogs” (also referred to as gundogs or bird dogs) are subdivided by function—that is, how they hunt. They are spaniels, pointers, setters, retrievers, and the European utility breeds. Of these, spaniels are generally considered the oldest. Early authorities divided the spaniels not by breed but by type: either water spaniels or land spaniels. The land spaniels came to be subdivided by size. The larger types were the “springing spaniel” and the “field spaniel,” and the smaller, which specialized on flushing woodcock, was known as a “cocking spaniel.” ~~How many breeds are in this group? 31~~ 1. American Water Spaniel a. Country of origin: USA (lake country of the upper Midwest) b. Original purpose: retrieve from skiff or canoes and work ground c. Other Names: N/A d. Very Brief History: European immigrants who settled near the great lakes depended on the region’s plentiful waterfowl for sustenance. The Irish Water Spaniel, the Curly-Coated Retriever, and the now extinct English Water Spaniel have been mentioned in histories as possible component breeds. e. Coat color/type: solid liver, brown or dark chocolate. A little white on toes and chest is permissible. -

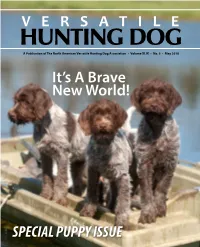

V E R S a T I L E It's a Brave New World! SPECIAL PUPPY ISSUE

VERSATILE HUNTING DOG A Publication of The North American Versatile Hunting Dog Association • Volume XLIX • No. 5 • May 2018 It’s A Brave New World! SPECIAL PUPPY ISSUE VERSATILE IF SOMEONE HUNTING DOG Volume XLIX • No. 5 • May 2018 NAVHDA International Officers & Directors David A. Trahan President TOLD YOU THAT Bob Hauser Vice President Steve J. Greger Secretary Richard Holt Treasurer Chip Bonde Director of Judge Development Andy Doak Director of Promotions FEATURES Tim Clark Director of Testing Tim Otto Director of Publications Steve Brodeur Registrar 4 It’s A Brave New World! • by Judy Zeigler Tracey Nelson Invitational Director Marilyn Vetter Past President 8 Sporting Breeds In Demand For Explosives Detection Work • by Penny Leigh Versatile Hunting Dog Publication Staff 14 The Healing • by Kim McDonald Mary K. Burpee Editor/Publisher Erin Kossan Copy Editor Sandra Downey Copy Editor 18 Anything & Everything • by Patti Carter Rachael McAden Copy Editor Patti Carter Contributing Editor Dr. Lisa Boyer Contributing Editor 22 We Made It Through • by Penny Wolff Masar 9191 Nancy Anisfield Contributing Editor/Photographer Philippe Roca Contributing Editor/Photographer 29 It’s Not Always Easy • by Patti Carter Wight Greger Women’s Editor Dennis Normile Food Editor 30 Test Prep Workshop • by Nancy Anisfield OF THE TOP 100 Maria Bondi Advertising Coordinator Marion Hoyer Webmaster Advertising Information DEPARTMENTS Copy deadline: 45 days prior to the month of President’s Message • 2 18 SPORTING publication. Commercial rates available upon request. All inquiries or requests for advertising should be On The Right Track • 4 * addressed to: Spotlight Dog • 25 DOGS EAT THE SAME NAVHDA PO Box 520 Ask Dr. -

Guide to Hunting in Germany

U.S. Forces Europe Hunting, Fishing, and Sport Shooting Program Guide to Hunting in Germany German Springer Spaniel (Deutscher Wachtelhund) Earth Dogs (Erdhunde) In hunting Fox and Badger, the Earth Dog is send into the ground or dens to drive out the game. Dachshund (Dackel or Teckel) and Terriers have been specially bred for generations for this work. They are the smallest hunting dogs and are noted for their bravery and tenacity. Dachshunds and Terriers also are used for trailing wounded game and on drive hunts. 09-10 U.S. Forces Europe Hunting, Fishing, and Sport Shooting Program Guide to Hunting in Germany Fox Terrier (Drahthaar Foxterrier) Fox Terrier (Glatthaar Foxterrier) 09-11 U.S. Forces Europe Hunting, Fishing, and Sport Shooting Program Guide to Hunting in Germany Hunting Terrier (Deutscher Jagdterrier) Long Haired Dachshund (Langhaardackel) 09-12 U.S. Forces Europe Hunting, Fishing, and Sport Shooting Program Guide to Hunting in Germany Rough Haired Dachshund (Rauhaardackel) Short Haired Dachshund (Kurzhaardackel) 09-13 U.S. Forces Europe Hunting, Fishing, and Sport Shooting Program Guide to Hunting in Germany Miniature Dachshund (Zwergdackel) Die Dackelfamilie mit Jäger und Magd, by Adolf Eberle, 1843-1914 09-14 U.S. Forces Europe Hunting, Fishing, and Sport Shooting Program Guide to Hunting in Germany Hounds (Jagende Hunde, Laufhunde) Hounds are the oldest species of hunting dogs. They are used in packs to hunt for hare and fox and are usually kept in kennels. Alpine Dachsbracke (Alpenländische Dachsbracke) Westphalian Dachsbracke (Westphälische Dachsbracke) 09-15 U.S. Forces Europe Hunting, Fishing, and Sport Shooting Program Guide to Hunting in Germany Deutsche Bracke (Deutsche Bracke) Deutsche Bracke (Deutsche Bracke) 09-16 U.S. -

Domestic Dog Breeding Has Been Practiced for Centuries Across the a History of Dog Breeding Entire Globe

ANCESTRY GREY WOLF TAYMYR WOLF OF THE DOMESTIC DOG: Domestic dog breeding has been practiced for centuries across the A history of dog breeding entire globe. Ancestor wolves, primarily the Grey Wolf and Taymyr Wolf, evolved, migrated, and bred into local breeds specific to areas from ancient wolves to of certain countries. Local breeds, differentiated by the process of evolution an migration with little human intervention, bred into basal present pedigrees breeds. Humans then began to focus these breeds into specified BREED Basal breed, no further breeding Relation by selective Relation by selective BREED Basal breed, additional breeding pedigrees, and over time, became the modern breeds you see Direct Relation breeding breeding through BREED Alive migration BREED Subsequent breed, no further breeding Additional Relation BREED Extinct Relation by Migration BREED Subsequent breed, additional breeding around the world today. This ancestral tree charts the structure from wolf to modern breeds showing overlapping connections between Asia Australia Africa Eurasia Europe North America Central/ South Source: www.pbs.org America evolution, wolf migration, and peoples’ migration. WOLVES & CANIDS ANCIENT BREEDS BASAL BREEDS MODERN BREEDS Predate history 3000-1000 BC 1-1900 AD 1901-PRESENT S G O D N A I L A R T S U A L KELPIE Source: sciencemag.org A C Many iterations of dingo-type dogs have been found in the aborigine cave paintings of Australia. However, many O of the uniquely Australian breeds were created by the L migration of European dogs by way of their owners. STUMPY TAIL CATTLE DOG Because of this, many Australian dogs are more closely related to European breeds than any original Australian breeds.