“The Choosing of a Proper Hobby”: Sir William Crowther and His Library1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Political Writings 2009-10

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library Information, analysis and advice for the Parliament BIBLIOGRAPHY www.aph.gov.au/library Selected Australian political writings 2009‐10 Contents Biographies ............................................................................................................................. 2 Elections, electorate boundaries and electoral systems ......................................................... 3 Federalism .............................................................................................................................. 6 Human rights ........................................................................................................................... 6 Liberalism and neoliberalism .................................................................................................. 6 Members of Parliament and their staff .................................................................................... 7 Parliamentary issues ............................................................................................................... 7 Party politics .......................................................................................................................... 13 Party politics- Australian Greens ........................................................................................... 14 Party politics- Australian Labor Party .................................................................................... 14 Party politics- -

Case Study: Tasmania

1968 the ACF purchased private land to add to the that Australia’s population be kept at the “optimum.” Alfred National Park in East Gippsland, with funds The submission was based on papers by Barwick, Chit- raised by ACF Councillor Sir Maurice Mawby, the tleborough, Fenner, and future ACF president H.C. Managing Director of Conzinc Riotinto Australia “Nugget” Coombs, a people-hater to rival Philip him- (CRA), now Rio Tinto—the Queen’s own mining com- self. Coombs once said, “The whole [human] species pany. Mawby was chairman of the ACF’s Benefactors [has] become itself a disease. [T]he human species and National Sponsors Committee. [is] like a cancerous growth reproducing itself beyond control.” Eradicate the ‘Plague’ . of People In the Nov. 23, 1970 issue of the Melbourne Herald, Prince Philip authored a full-page feature entitled Case Study: Tasmania “Wildlife Crisis: Every Life Form Is in Danger.” Under the subhead “Plague of People,” he declared: “The phe- nomenon now widely described as the population ex- Tasmania today is a Green basket case. Over half of the plosion means that the human race has reached plague state is locked up in a complex system of nature re- proportions.” Upon assuming the presidency of the serves, including Australia’s biggest declared wilder- ACF a few months later, the Duke emphasized the im- ness area, in the Southwest (Figure 4). Green policies portance of two conservation issues: national parks and have decimated traditional Tasmanian economic activi- population. The loudest early voices in Australia for ties such as forestry and agriculture, and it has the population reduction were all “experts” associated with lowest population growth in Australia. -

Paradoxes of Protection Evolution of the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service and National Parks and Reserved Lands System

Paradoxes of Protection Evolution of the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service and National Parks and Reserved Lands System By Dr Louise Crossley May 2009 A Report for Senator Christine Milne www.christinemilne.org.au Australian Greens Cover image: Lake Gwendolen from the track to the summit of Frenchmans Cap, Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Photo: Matt Newton Photography Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................. 1 1. THE INITIAL ESTABLISHMENT OF PARKS AND RESERVES; UTILITARIANS VERSUS CONSERVATIONISTS 1915-1970....................................................................... 3 1.1 The Scenery Preservation Board as the first manager of reserved lands ............................................................ 3 1.2 Extension of the reserved lands system ................................................................................................................... 3 1.3The wilderness value of wasteland ........................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Inadequacies of the Scenery Protection Board ...................................................................................................... 4 2. THE ESTABLISHMENT AND ‘GLORY DAYS’ OF THE NATIONAL PARKS AND WILDLIFE SERVICE 1971-81 ........................................................................................... 6 2.1 The demise of the Scenery Preservation Board and the Lake Pedder controversy -

Power & Environmental Policy : Tasmanian Ecopolitics from Pedder

Power & Environmental Policy: Tasmanian Ecopolitics from Pedder to Wesley Vale. bY Catherine M. Crowley" B. Arts, (Mon.), Dip. Ed., (Rusden) & Dip. Rec., (Phillip Inst.). Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia, May 1994. 1 all other publications by the name of Kate Crowley. Statements This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any tertiary institution. To the best of the candidate's knowledge and belief, this thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text of the thesis. This thesis may be available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. v1/1274 Catherine M Crow elf - Date ii Power and Environmental Policy: Tasmanian Eco politics from Pedder to Wesley Vale Abstract It is argued that the realisation of ecopolitical values, interests and demands is inevitably constrained by material interests within advanced industrial societies. The policy environment in the state of Tasmania is examined, and both a traditional affirmation and accommodation of the goals of industrial development, and a resistance to the more recent ecopolitical challenge to established state interests is found. However, a review of four key environmental disputes finds that the politics of ecology ('ecopolitics'), despite routine constraint by material interests, continues to defy predictions -

Structure and Ideology in the Tasmanian Labor Party

Structure and Ideology in the Tasmanian Labor Party: Postmaterialism and Party change ,- By Peter James Patmore LL.B., Dip. Crim. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements fo r the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania, March 2000 II This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously pubJished or written by another person except where due acknowledgment is made in the text ofthe thesis. ................�................. �---=;,.......... Peter Patmore 23" February 2000. III This thesis is not to be made available for loan or copying for two years fo llowing the date this statement is signed. Following that time the thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Peter Pa tmore 23'" February 2000 iv ABSTRACT The Tasmanian Labor Party has found itself, like many western social democratic parties, recently subject to challenge; not from its traditional enemy, the economic right, but froma new postmaterialist left. This thesis considers the concept of postmaterialism, its rise and role in the fo rmation of new ecocentric political parties, and its impact on the structure, ideology and electoral strategy of the Tasmanian Labor Party. Maurice Duverger's typology of political parties has been used to elucidate and consider the characteristics and fo rmation of political parties and the importance of electoral systems - particularly proportional representation - in achieving representational success. -

Earle Page and the Imagining of Australia

‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA ‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA STEPHEN WILKS Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, Or what’s a heaven for? Robert Browning, ‘Andrea del Sarto’ The man who makes no mistakes does not usually make anything. Edward John Phelps Earle Page as seen by L.F. Reynolds in Table Talk, 21 October 1926. Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463670 ISBN (online): 9781760463687 WorldCat (print): 1198529303 WorldCat (online): 1198529152 DOI: 10.22459/NPM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This publication was awarded a College of Arts and Social Sciences PhD Publication Prize in 2018. The prize contributes to the cost of professional copyediting. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: Earle Page strikes a pose in early Canberra. Mildenhall Collection, NAA, A3560, 6053, undated. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Illustrations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Abbreviations . xiii Prologue: ‘How Many Germans Did You Kill, Doc?’ . xv Introduction: ‘A Dreamer of Dreams’ . 1 1 . Family, Community and Methodism: The Forging of Page’s World View . .. 17 2 . ‘We Were Determined to Use Our Opportunities to the Full’: Page’s Rise to National Prominence . -

Parliamentary Experiences of the Tasmanian Greens: the Politics of the Periphery1

in Ecopolitics: Thought and Action, Vol 1, No 1, 2000, pp. 53-71. Parliamentary Experiences of the Tasmanian Greens: The Politics of the Periphery1 i Kate Crowley ABSTRACT This paper reflects upon the green political trajectory in Tasmania from the founding in 1972 of the world's first green2 party, the United Tasmania Group, to the recent 'electoral reform’ that in effect disenfranchised most of the Tasmanian parliamentary greens (Crowley, 2000). It argues that green politics, whilst fundamentally transforming the island state of Tasmania in part through its nature conservation successes, has remained a politics at the periphery that is resisted by both the major parties. This peripheralisation is not entirely owed to the green's longstanding pursuit of wilderness preservation, however, but also to their preoccupation both with progressive politics and democratic accountability that has led them into state parliament where they have twice achieved the balance of power (Crowley, 1996; 1999b). This paper recounts familiar terrain with its description of Tasmania as a conservative, economically marginal island state that has pursued a development formula based upon resource exploitation and hydroindustrialisation that went unchallenged until the rise of the greens. It shows how Tasmania's green politics, perhaps unlike green politics in more vital, less marginal contexts, has been a politics of contrast and change, ecocentric to its core, but strategically concerned with broader social reformism. By considering the failure of both green minority governments (Labor-Green 1989-91; and Liberal-Green 1996-8), it further reinforces how much the major parties have resisted green efforts both to share the state political stage and to move more than rhetorically away from resource based developmentalism3. -

Tasmania's Green Disease

Tasmania’s Green Disease DAVID BARNETT Going Green is a great way to end up in the red. A look at the decay of the island State. ASMANIA is chronically ill herself as a national from the Green virus, and figure, and to win a seat wasting away. According to in the Tasmanian Leg- T the Australian Statistician, islative Assembly. Tasmania is the only State or Territory It is also Bob whose population will decline—regardless Hawke, who was Prime of which of the ABS’s three sets of assump- Minister when the tions are used about immigration, fertility Wesley Vale project Photo removed for reasons of copyright and interstate population flows. By the was proposed, and year 2051, Tasmania’s population will be Graham Richardson, down from its present level of 473,000 to Hawke’s environment either (depending on which set you adopt) minister. You should 462,100, 445,700 or 418,500 people. also include Tasma- Perhaps Tasmanians are fortunate that nian Senator Shayne their fertile and pleasant island has be- Murphy, although he come an economic backwater, and a place made his contribution for mainlanders to escape the hustle and as an official of the Construction, Forestry Robin Gray a thermal power station and bustle which goes along with economic and Mining Union (CFMEU). a lump of money to abandon the Franklin activity, the roar of urban traffic which is Tasmania’s unemployment rate is 10.6 project. the consequence of two cars in every ga- per cent, against a national average of 7.5 Gray saw himself as another Charles rage. -

Reuben Finn Conry

National winner Year level 8 Reuben Finn Conry Calvin Christian School Lake Pedder And The Franklin Dam Reuben Conry 1 Lake Pedder And The Franklin Dam ‘People And Power’ 2019 National History Challenge 8.3 SOSE Mrs Beeton By Reuben Finn Conry Word Count-990 In 1979, the battle to save Lake Pedder was lost. This was simply because a few people in power decided to act. The events of the flooding of Lake Pedder has affected Tasmania, as well as Australia, and has a powerful message with its story: with great power comes great responsibilities. Lake Pedder And The Franklin Dam Reuben Conry 2 Lake Pedder was a beautiful Glacial lake surrounded by mountains. It had been called ‘The Jewel of Tasmania’ and many other titles that reflected the serene beauty of this particular lake. So it came as a shock to many when Eric Reece AKA ‘Electric Eric’ announced that Lake Pedder would be modified. The modification included flooding Lake Pedder. The Hydro-Electric Commision had joined with the Tasmanian government to make a dam so that it could supply Tasmania with electricity. While this would be beneficial for a developing state, there were other ways to get this power and save a priceless location. This started a battle that would change the way people thought about people power, and prove that everyday people could change the state that we live in. The people of Tasmania worked together to attempt to stop the flooding of Lake Pedder. There was a massive response from the people of Hobart, creating a ten thousand signature petition, the highest amount of signatures put together for one petition in Tasmania. -

Wilderness Karst in Tasmanian Resource Politics

WILDERNESS KARST IN TASMANIAN RESOURCE POLITICS by Kevin Kiernan Tasmanian Wilderness Society Until the early 1970s karst resources were largely un recognised in decisions regarding land-use in Tasmania. Over the past decade growing concern for the protection of the wilderness landscape of the island's south-west has stimulated the growth both of community based environmental interest groups and of protective agencies within the administrative machinery of government. Both have attracted individuals with expertise in karst and a personal committment to its proper management. Largely through their awareness and individual efforts, caves and karst have been promoted as little-known but worth while components of the wilderness. The positive results of this have included a stimulus to our knowledge of karst, an increase in public awareness of karst and a strengthening of the case for the prevention of the wilderness area. On the negative side, there may be some potentially dysfunctional consequences attached to the politicising of karst, including the loss of any "first strike" advantage which might otherwise have been available to karst advocates dealing with areas where it is a primary rather than subsidiary resource; and also the developmnent in some sectors of the community of an "anti-cave" ethos which might other wise not yet have arisen. Proceedings of 14th Conference of the ASF 1983 25 I WILDERNESS KARST IN TASMANIAN RESOURCE POLITICS KIERNAN INTRODUCTION The obj ect of this paper is to trace the nature of and changes in the management status over the past decade of one s.all co.ponent of the Tas.anian environ.ent : karst. -

TASMANIA: the Strange and Verdant Politics of a Strange and Verdant Island

TASMANIA: The Strange and Verdant Politics of a Strange and Verdant Island Dr. Peter Hay University of Tasmania © 2000 Peter Hay Like Prince Edward Island, Tasmania is a full partner, and the smallest partner, within its nation's federal compact, though its population of approximately 450,000 would fit very comfortably within any of the major cities of mainland Australia, and its capital city, Hobart, is home to fewer people than live in some of the local government areas of middle suburban Melbourne. The island - my island - is in the shape of an inverted heart, and hangs like a teardrop off the southern coast of eastern Australia, from which it is separated by Bass Strait, a shallow but turbulent body of water. Melbourne is eight sailing hours away on a large car ferry. There is no land to the west until one fetches up against Cape Horn, and nothing to the south before one hits the Antarctic ice shelf. Tasmania is 26,000 square miles. (By way of comparison, Ireland is 32,000 square miles, larger by about a fifth.) It is "a land of innumerable streams, rivers and mountains, with a heavy rainfall on the western side . brought by the prevailing westerlies that blow, unimpeded, more than halfway across the southern oceans" (Robson, updated by Roe 1997: 2). Geologically Tasmania is part of the supercontinent of Gondwanaland. The Southwest, Central Highlands and much of the West Coast remain largely uninhabited, a temperate wetland with high wilderness value, much of it under National Park, and on the World Heritage Register - about which, more shortly. -

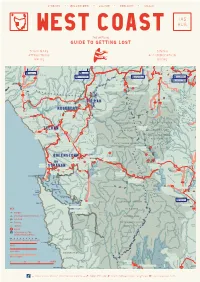

West Coast Municipality Map.Pdf

CAMPBELL NeaseySTRAHAN • QUEENSTOWN • ZEEHAN • ROSEBERY • TULLAH12 Plains 10 THE RANGE 6 Blue Peak 18 4 16 5 Mt 4 DAZZLER Hill 17 Duncan 10 3 5 17 16 12 Ri 13 ver 9 14 7 EUGENANA ARLETONT LATROBE Rive SOUT H River SPALFORD TAS HARFORD River 14 UPPER KINDREDMELROSE Horton R River RIANA 19 5 Guide NATONE River 45 HAMPSHIRE PALOONA ons GUNNS y SPRENT L BALFOUR R AUS 13PLAINS Rubicon Mt Balfour PRESTON 9 LOWER SASSAFRAS Mt CASTRA Mersey R 27 Mt Bertha Emu HEKA BARRINGTON Frankland r ARRINGAW Blythe River WESTKeith COAST Lake 22 17 13 River Paloona n Do Arthu River NOOK R Lindsay THE OFFICIAL iver 49 1106 ST VALENTINES PK River NIETTA SHEFFIELD Mt Hazelton GUIDEDeep TO GETTING CreeLOSTk WILMO T WEST SUNNYSIDE 5 Gully KENTISH PARKHAM Dempster SOUTH LAKE River Leven ROLAND River 78 Savage BARRINGTON 21 Ck NIETTA LOWER Pedder TOWN MAPS GUILDFORD DININGCLAUDEROAD BEULAH Mt Bischoff River Talbots 7 Mt Cleveland WARATAH 1339 BLACK BLUFF STAVERTON13 Lagoon River Lake C157 MOLTEMA 759 Mt Norfolk ATTRACTIONS zlewood 856 ACCOMMODATION1231 MT ROLAND Gairdner CETHANA ELIZABETH C136 GOWRIE PARK ARTHUR PIEMAN Hea 11 TOWN Mt Vero WALKS B23 43 MOINA SHOPS WEEGENA Mt Pearce Mt Claude r C138 CONSERVATION AREA e 1001 W 10 y a w Med v i 16 Mt Cattley River 13River DUNORLAN R River Mersey 19 LEMANA SAVAGE Lake 30 C137 RED HILLS r Rive Lea Iris LAKE River 26 LORINNA RIVER CETHANA LIENA KING 11 River River Middlesex NEEDLES C132 SOLOMONS 4 MOLE STANLEY BURNIE Plains C139 Interview CAVE MAYBERRY C169 Coldstream River Mt Meredith River Que River CREEK R C249 26 River