LDS Hispanic Americans and Lamanite Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JULY 2004 Liahona One Million Milestone in Mexico, P

THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • JULY 2004 Liahona One Million Milestone in Mexico, p. 34 Pioneering in Moldova, p. 20 Knowing Who You Are, p. F2 THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • JULY 2004 Liahona FOR ADULTS 2 First Presidency Message: Miracles of Faith President Thomas S. Monson 8 Book of Mormon Times at a Glance: Chart 2—Alma through Mormon and Moroni 25 Visiting Teaching Message: Feeling the Love of the Lord through Prayer ON THE COVER 26 Protecting Your Child from Gang Influence Dennis J. Nordfelt Photography by Don L. Searle. 30 Book of Mormon Principles: Submitting Our Will to the Father’s Elder Benjamin De Hoyos 34 One Million in Mexico Don L. Searle 44 Latter-day Saint Voices My Child Is Drowning! Hirofumi Nakatsuka Two-of-a-Kind Table Son Quang Le and Beth Ellis Le She Was My Answer Dori Wright 48 Comment FOR YOUTH 15 Poster: Make Waves THE FRIEND COVER 16 All Is Well Elder David B. Haight Illustrated by Steve Kropp. 20 A Message from Moldova Karl and Sandra Finch 29 Outnumbered Paolo Martin N. Macariola 47 Did You Know? THE FRIEND: FOR CHILDREN F2 Come Listen to a Prophet’s Voice: Knowing Who You Are President James E. Faust F4 Sharing Time: A Special Day Sheila E. Wilson F6 From the Life of President Heber J. Grant: Learning to Sing F8 Poster Article: Temples Bless Families F10 Courage and a Kind Word Patricia Reece Roper F14 Making Friends: Medgine Atus of Miramar, Florida Tiffany E. -

Early Mormon Exploration and Missionary Activities in Mexico

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 22 Issue 3 Article 4 7-1-1982 Early Mormon Exploration and Missionary Activities in Mexico F. LaMond Tullis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Tullis, F. LaMond (1982) "Early Mormon Exploration and Missionary Activities in Mexico," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 22 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol22/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Tullis: Early Mormon Exploration and Missionary Activities in Mexico early mormon exploration and missionary activities in mexico F lamond tullis in 1875 a few days before the first missionaries to mexico were to depart brigham young changed his mind rather than have them travel to california where they would take a steamer down the coast and then go by foot or horseback inland to mexico city brigham asked if they would mind making the trip by horseback going neither to california nor mexico city but through arizona to the northern mexican state of sonora a round trip of 3000 miles he instructed them to look along the way for places to settle and to deter- mine whether the lamanitesLamanites were ready to receive the gospel but brigham young had other things in mind the saints might need another place of refuge and advanced -

The Beginning of a Unique Church School in Mexico

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 52 Issue 4 Article 5 12-1-2013 Benemérito de las Américas: The Beginning of a Unique Church School in Mexico Barbara E. Morgan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Morgan, Barbara E. (2013) "Benemérito de las Américas: The Beginning of a Unique Church School in Mexico," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 52 : Iss. 4 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol52/iss4/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Morgan: Benemérito de las Américas: The Beginning of a Unique Church Scho Benemérito de las Américas The Beginning of a Unique Church School in Mexico Barbara E. Morgan n a bittersweet ceremony on January 29, 2013, Elder Daniel L. Johnson, Ia member of the Seventy and President of the Mexico Area, announced the transformation of Benemérito de las Américas, a Church-owned high school in Mexico City, into a missionary training center at the end of the school year.1 To the emotional students and faculty at the meet- ing, Elders Russell M. Nelson and Jeffrey R. Holland of the Quorum of the Twelve explained the urgent need to provide additional facilities for missionary training in the wake of President Thomas S. Monson’s announcement that minimum ages for missionary service were being lowered and the consequent upsurge in numbers.2 While The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has owned and operated other schools, this school was unique in the expansive role it played in Mexi- can Church history. -

Full Journal

Advisory Board Alan L. Wilkins, chair James P. Bell Donna Lee Bowen Douglas M. Chabries Doris R. Dant Randall L. Hall Editor in Chief John W. Welch Church History Board Richard Bennett, chair 19th-century history Brian Q. Cannon 20th-century history Kathryn Daynes 19th-century history Gerrit J. Dirkmaat Joseph Smith, 19th-century Mormonism Steven C. Harper documents Frederick G. Williams cultural history Liberal Arts and Sciences Board Eric Eliason, chair English, folklore Barry R. Bickmore geochemistry David C. Dollahite faith and family life Susan Howe English, poetry, drama Neal Kramer early British literature, Mormon studies Steven C. Walker Christian literature Reviews Board Eric Eliason co-chair John M. Murphy co-chair Angela Hallstrom literature Greg Hansen music Emily Jensen new media Trevor Alvord new media Megan Sanborn Jones theater and media arts Herman du Toit art, museums Specialists Involving Readers Casualene Meyer poetry editor in the Latter-day Saint Thomas R. Wells Academic Experience photography editor STUDIES QUARTERLY BYU Vol. 52 • No. 4 • 2013 ARTICLES 4 Loyal Opposition: Ernest L. Wilkinson’s Role in Founding the BYU Law School Galen L. Fletcher 49 What Happened to My Bell-Bottoms? How Things That Were Never Going to Change Have Sometimes Changed Anyway, and How Studying History Can Help Us Make Sense of It All Craig Harline 77 Revisiting the Seven Lineages of the Book of Mormon and the Seven Tribes of Mesoamerica Diane E. Wirth 89 Benemérito de las Américas: The Beginning of a Unique Church School in Mexico Barbara E. Morgan 117 “My God, My God, Why Hast Thou Forsaken Me?”: Psalm 22 and the Mission of Christ Shon Hopkin REVIEW ESSAY 152 Likening in the Book of Mormon: A Look at Joseph M. -

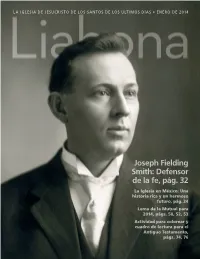

Joseph Fielding Smith: Defensor De La Fe, Pág

LA IGLESIA DE JESUCRISTO DE LOS SANTOS DE LOS ÚLTIMOS DÍAS • ENERO DE 2014 Joseph Fielding Smith: Defensor de la fe, pág. 32 La Iglesia en México: Una historia rica y un hermoso futuro, pág. 24 Lema de la Mutual para 2014, págs. 50, 52, 53 Actividad para colorear y cuadro de lectura para el Antiguo Testamento, págs. 74, 76 “Tal vez algunas de ustedes sientan que no pueden salir del estanque contami- nado, que sus circunstancias son muy difíciles, que sus pruebas son dema- siado complejas y que sus tentaciones son demasiado grandes… Recuerden: el tallo del lirio acuático crece en la adversidad y, así como el tallo sostiene al lirio, su fe las sostendrá y elevará”. Mary N. Cook, ex Segunda Consejera de la Presidencia de las Mujeres Jóvenes, “Las anclas del testimonio”, Liahona, mayo de 2008, pág. 122. Liahona, enero de 2014 18 MENSAJES 24 Pioneros en toda tierra: 12 Los profetas del Antiguo Despliegue de la Iglesia Testamento: Adán 4 Mensaje de la Primera en México: De la lucha Presidencia: El mejor momento a la fortaleza 14 Clásicos del Evangelio: para plantar un árbol Por Sally Johnson Odekirk La divina Trinidad Por el presidente Dieter F. Uchtdorf Santos de los Últimos Días de Por el presidente Gordon B. Hinckley México sacrificaron mucho para 7 Mensaje de las maestras 17 La enseñanza de Para la visitantes: La misión divina establecer la Iglesia en su país. Fortaleza de la Juventud: La de Jesucristo: Ejemplo 32 Leal y fiel: Inspiración de observancia del día de reposo la vida y las enseñanzas de 38 Voces de los Santos ARTÍCULOS DE INTERÉS Joseph Fielding Smith de los Últimos Días Por Hoyt W. -

Januari 2014 Liahona

GEREJA YESUS KRISTUS DARI ORANG-ORANG SUCI ZAMAN AKHIR • JANUARI 2014 Joseph Fielding Smith: Pembela Iman, hlm. 32 Gereja di Meksiko— Sejarah yang Melimpah, Masa Depan yang Indah, hlm. 24 Tema Kebersamaan Tahun 2014, hlm. 50, 52, 53 Kegiatan mewarnai dan Bagan Bacaan untuk Perjanjian Lama, hlm. 74, 76 “Beberapa dari Anda mungkin merasa bahwa Anda tidak bisa maju karena keadaan sekitar Anda, bahwa keadaan Anda terlalu sulit, kesulitan Anda terlalu berat, godaan Anda terlalu besar .… Ingatlah, tangkai dari bunga lili tumbuh dalam kesulitan, dan sewaktu tangkai itu mengangkat bunga lili, iman Anda akan mendukung dan mengangkat Anda.” Mary N. Cook, mantan Penasihat Kedua dalam presidensi umum Remaja Putri, “Sauh Kesaksian,” Liahona, Mei 2008, 122. Liahona, Januari 2014 18 PESAN ARTIKEL-ARTIKEL UTAMA DEPARTEMEN 4 Pesan Presidensi Utama: Waktu 18 Menghadapi Masa Depan 8 Catatan Konferensi Terbaik untuk Menanam Pohon dengan Iman dan Pengharapan Oktober 2013 Oleh Presiden Dieter F. Uchtdorf Oleh Penatua M. Russell Ballard Kita harus mendedikasikan dan 10 Kita Berbicara tentang Kristus: 7 Pesan Pengajaran Berkunjung: menguduskan kehidupan kita Dari Kegelapan Menuju Terang Misi Ilahi Yesus Kristus: Teladan untuk urusan Juruselamat, de- Nama dirahasiakan ngan berjalan dalam iman dan 12 Para Nabi Perjanjian Lama: bekerja dengan keyakinan. Adam 25 Pionir di Setiap Negeri: 14 Injil Klasik: Tubuh Meksiko Terungkap—dari Ke-Allah-an Ilahi Perjuangan Menuju Kekuatan Oleh Presiden Gordon B. Hinckley Oleh Sally Johnson Odekirk Para Orang Suci Zaman Akhir di 17 Mengajarkan Untuk Kekuatan Meksiko berkurban banyak untuk Remaja: Pengudusan Hari Sabat membangun Gereja di negara mereka. 38 Suara Orang Suci Zaman Akhir 33 Teguh dan Setia: Inspirasi dari 80 Sampai Kita Bertemu Lagi: Kehidupan dan Ajaran-Ajaran Dapatkah Dia Melihat Saya? Joseph Fielding Smith Oleh Teresa Starr Oleh Hoyt W. -

History Through Seer Stones: Mormon Historical Thought 1890-2010

History Through Seer Stones: Mormon Historical Thought 1890-2010 by Stuart A. C. Parker A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Stuart A. C. Parker 2011 History Through Seer Stones : Mormon Historical Thought 1890-2010 Stuart A. C. Parker Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2011 Abstract Since Mark Leone’s landmark 1979 study Roots of Modern Mormonism , a scholarly consensus has emerged that a key element of Mormon distinctiveness stems from one’s subscription to an alternate narrative or experience of history. In the past generation, scholarship on Mormon historical thought has addressed important issues arising from these insights from anthropological and sociological perspectives. These perspectives have joined a rich and venerable controversial literature seeking to “debunk” Mormon narratives, apologetic scholarship asserting their epistemic harmony or superiority, as well as fault-finding scholarship that constructs differences in Mormon historical thinking as a problem that must be solved. The lacuna that this project begins to fill is the lack of scholarship specifically in the field of intellectual history describing the various alternate narratives of the past that have been and are being developed by Mormons, their contents, the methodologies by which they are produced and the theories of historical causation that they entail. This dissertation examines nine chronica (historical narratives -

La-Primera-Conferencia-General-De

INFORME OFICIAL de la PRIMERA CONFERENCIA GENERAL DE AREA PARA MEXICO Y CENTROAMERICA de LA IGLESIA DE JESUCRISTO DE LOS SANTOS DE LOS ULTIMOS DIAS verificada en el Auditorio Nacional del Parque de Chapultepec en México, D. F. los días 25, 26 y 27 de agosto de 1972 Publicado por La Iglesia de Jesucristo de Los Santos de Los Ultimos Días Biblioteca SUD OFFICIAL REPORT of the FIRST AREA GENERAL CONFERENCE FOR MEXICO AND CENTRAL AMERICA Derechos reservados por la Corporación del Presidente de la Iglesia de Jesucris to de los Santos de los Ultimos Días 1973 1973 Corporation of the President of The Church of Jesús Christ of Latter-day Saints Printed in the United States of America by Deseret Press LA PRIMERA CONFERENCIA GENERAL DE AREA PARA MEXICO Y CENTROAMERICA DE LA IGLESIA DE JESUCRISTO DE LOS SANTOS DE LOS ULTIMOS DIAS La primera Conferencia General de Area para México y Centroamérica de La Iglesia de Jesucristo de los Santos delos Ultimos Días, se llevó a cabo los días 25, 26 y 27 de agosto de 1972 en la ciudad de México. Las siguientes sesiones se efectuaron en los lugares indicados: Viernes, 25 de agosto de 1972, 20:00 hs.: Programa de actividades........................................................... Auditorio Nacional Sábado, 26 de agosto, 10:00 hs.: Primera sesión general ...............................................................Auditorio Nacional Sábado, 26 de agosto, 14:00 hs.: Segunda sesión general..............................................................Auditorio Nacional Sábado, 26 de agosto, 19:00 hs.: Reunión del Sacerdocio Aarónico Centro de la Estaca de la Cd. de México en Churubusco Sábado, 26 de agosto, 19:00 hs.: Reunión del Sacerdocio de Melquisedec ............................Centro de la Estaca de la Cd. -

Mormons, We Spoke to Bate Lije? Mormons in Japan, Russia and A: Well, Yes, I Suppose, Essen- Mexico, and Some Say the Church Tially

ON THE RECORD ON NON-AMERICAN G.A.S are imposed. Q: What about gay people who Q: When The Chronicle did a feel God made them that way? series last year on the global impact You're saying they must lead a celi- of the Mormons, we spoke to bate liJe? Mormons in Japan, Russia and A: Well, yes, I suppose, essen- Mexico, and some say the church tially. A lot of people live a celi- MAIN MORMON" has not moved fast enough to give bate life. Lots of them. A third of power and authority to Mormons the people in the United States jrom other ethnic groups. are now single. Many of them A: It'll come. It's coming. It's live a celibate life. This spring, while in Northern CaliJornia to deliver an address to the World coming. We have people from Q: But what homosexuals say is Forum of Silicon Valley, ws Church President Gordon B. Hinckley was in- Mexico, Central America, South they don't have the opportunity to terviewed by the San Francisco Chronicle. These are excerptsfrom that America, Japan, Europe among many and be monogamous and published interview. the general authorities. And that faithful. This interview was published under the above heading in the 13 April will increase, I think, inevitably. A: We believe that mamage, 1997 San Francisco Sunday Examiner & Chronicle. Copy right 1997, As we become more and more a of a man and a woman, is that Sunday Examiner & Chronicle. Reprinted by permission. world church, we'll have greater which is ordained of God for the world representation. -

Clases De Quinto Domingo

CLASES DE QUINTO DOMINGO Mayo 2016 Estimados hermanos: Hemos aprobado la enseñanza de estas lecciones sobre la Historia de la Iglesia en nuestro país con el propósito de fortalecer el testimonio de los santos en México y para el beneficio de las futuras generaciones. Esta lección sobre los templos nos permite reconocer los grandes sacrificios que hicieron muchos de los santos mexicanos para que hoy disfrutemos las grandes bendiciones que nos brinda “La cadena de perlas” de los trece templos que adornan nuestro país. La historia brinda grandes oportunidades de aprender sobre aquellas experiencias que forjaron el carácter y la determinación de los primeros santos en épocas difíciles. Al estudiar y conocer los hechos y a las personas que los protagonizaron, podremos descubrir de manera personal, nuestro lugar y nuestro papel en la historia que día a día se sigue escribiendo. Con amor sus hermanos, Presidencia de Área México Élder Benjamín De Hoyos Élder Paul B. Pieper Élder Arnulfo Valenzuela 1 ÍNDICE DE LAS LECCIONES DE LA HISTORIA DE LA IGLESIA EN MÉXICO 1. Cómo llegó el Evangelio y El Libro de Mormón a México. 2. La expedición del apóstol Moses Thatcher a la Ciudad de México en 1879. 3. Los colonizadores mormones en Chihuahua y Sonora. 4. Reapertura de la Misión Mexicana en 1901. 5. Las tribulaciones de los santos durante la Revolución. 6. La Tercera Convención y la reunificación de la Iglesia en 1946 7. La Iglesia y la educación to Presentamos la lección para 5 domingo de mayo de 2016: 8ª Lección: “Templos modernos en México” INSTRUCCIONES: 1. -

Clark Memorandum: Fall 1994 J

Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons The lC ark Memorandum Law School Archives Fall 1994 Clark Memorandum: Fall 1994 J. Reuben Clark Law Society J. Reuben Clark Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/clarkmemorandum Part of the Legal Biography Commons, Legal Education Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation J. Reuben Clark Law Society and J. Reuben Clark Law School, "Clark Memorandum: Fall 1994" (1994). The Clark Memorandum. 16. https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/clarkmemorandum/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Archives at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The lC ark Memorandum by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTENTS FALL 1994 1-1 lkese Hanscn Dean’s Message 3 Dean Too Much Lair< Tho Little Consemus 4 Scott W Camcron Edit07 Eruce C Haf’cn Charles D Cranney 14 AssoL,iate Editor Linda A Sullivan Art Director Keepers of the Flame 22 Elder E Burton I-Ioward John Snyder Photog?upher A Safe Return 28 Michael Goldsmith MEMORANDA Young Mission Presidents 13 The Call to Setve 14 Mark Zobrist An Interview with Mary Hales Hoaglad, New Career Services Director 35 F 1994 LA ICLESIA UE OC LOS LLT MOS The Clark Memorandum is published by the 1 Reuben Clatk Law Society and the J Rcubeii Clark Law School, Brigham Young University Copyiigbt 1994 by Brigham Young Univet sity All Rights -

January 2014 Liahona

PIONEERS IN EVERY LAND Mexico Unfurled: FROM STRUGGLE TO STRENGTH Latter-day Saints in Mexico build on their heritage of faith to bring a beautiful future to their country. By Sally Johnson Odekirk Church Magazines n November 6, 1945, prayers were answered when the first group of Mexican Latter-day Saints arrived at the Mesa Arizona Temple to receive temple ordi- Onances in their native tongue. José Gracia, then president of the Monterrey Branch said, “We have come to do a great work for ourselves and for our fathers. Perhaps some of us have made sacrifices, but those that we have made are not in vain. We are joyous in having made them.” 1 President Gracia and those who traveled to the temple followed in the footsteps of early Mexican Latter-day Saint pioneers, who likewise sacrificed for the restored gospel. PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY ISRAEL GUTIÉRREZ; INSETS, FROM TOP: PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY CRAIG DIMOND; PHOTOGRAPH BY ISRAEL GUTIÉRREZ; INSETS, FROM TOP: PHOTO ILLUSTRATION PHOTO ILLUSTRATION JOHNSON ODEKIRK; PHOTOGRAPH BY SALLY LIBRARY; © GETTY IMAGES; PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF CHURCH HISTORY BY WELDEN C. ANDERSEN PHOTO ILLUSTRATION January 2014 25 Laying the Foundation A land of mountains, deserts, jungles, and exquisite coastlines, ancient Mexico was home to peoples who built beautiful temples and cities. Over the centuries, Mexicans built a strong foundation of faith and prayer that has helped them weather difficult times. While the Saints were establishing the Church in Utah, the Mexican people were working to restructure their society, including writing a new constitution that separated church and state. The gospel message came to Mexico President George Albert Smith visited Mexico and helped unify the members as he reached out to the Third Convention.