GAO-06-21 Commercial Aviation: Initial Small Community Air Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Airline Competition Plan Final Report

Final Report Airline Competition Plan Philadelphia International Airport Prepared for Federal Aviation Administration in compliance with requirements of AIR21 Prepared by City of Philadelphia Division of Aviation Philadelphia, Pennsylvania August 31, 2000 Final Report Airline Competition Plan Philadelphia International Airport Prepared for Federal Aviation Administration in compliance with requirements of AIR21 Prepared by City of Philadelphia Division of Aviation Philadelphia, Pennsylvania August 31, 2000 SUMMARY S-1 Summary AIRLINE COMPETITION PLAN Philadelphia International Airport The City of Philadelphia, owner and operator of Philadelphia International Airport, is required to submit annually to the Federal Aviation Administration an airline competition plan. The City’s plan for 2000, as documented in the accompanying report, provides information regarding the availability of passenger terminal facilities, the use of passenger facility charge (PFC) revenues to fund terminal facilities, airline leasing arrangements, patterns of airline service, and average airfares for passengers originating their journeys at the Airport. The plan also sets forth the City’s current and planned initiatives to encourage competitive airline service at the Airport, construct terminal facilities needed to accommodate additional airline service, and ensure that access is provided to airlines wishing to serve the Airport on fair, reasonable, and nondiscriminatory terms. These initiatives are summarized in the following paragraphs. Encourage New Airline Service Airlines that have recently started scheduled domestic service at Philadelphia International Airport include AirTran Airways, America West Airlines, American Trans Air, Midway Airlines, Midwest Express Airlines, and National Airlines. Airlines that have recently started scheduled international service at the Airport include Air France and Lufthansa. The City intends to continue its programs to encourage airlines to begin or increase service at the Airport. -

Press Release Nonstop Service to Orlando Coming to Yeager Airport

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS RELEASE NONSTOP SERVICE TO ORLANDO COMING TO YEAGER AIRPORT Starting February 14th, 2020, Spirit Airlines will add year-round, nonstop service to Orlando International Airport (MCO). The flights are going to be on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday of every week. This is the first time Yeager Airport has had a nonstop flight to Orlando since 2012. “This is an exciting opportunity for not only the airport but our passengers as well,” said Yeager Airport Director, Nick Keller. “We are all going to Disney World,” said Kanawha County Commission President Kent Carper. I would like to specifically thank Senator Manchin, Senator Capito, Congressman Mooney and Governor Justice for their help on this project, we could not have done it without them. I certainly would like to thank the staff and the Yeager Board for their hard work to make this happen. Without the completion of the Runway 5 rebuild and the restoration of the EMAS at Yeager Airport—a $25 Million project—this could not have happened. The very date that we are announcing this flight the rebuild has been finished for just four months.” Spirit will utilize Yeager Airport’s US Department of Transportation Small Community Air Service Development (SCASD) grant to initiate and market this service. The airline will operate the flight on Airbus 319 or 320s aircraft. “I am happy to see Spirit Airlines expanding their flight service to Orlando,” said Kanawha County Commissioner Hoppy Shores. “Yeager Airport is the Best Airport in West Virginia and we are expanding, and this low-cost carrier is helping make it happen.” 100 Airport Road – Suite 175 | Charleston, West Virginia 25311 | 304.344.8033 “The new flight to Orlando serviced by Spirit Airlines is a great addition to Yeager Airport,” said Kanawha County Commissioner Ben Salango. -

Nantucket Memorial Airport Page 32

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL AIR TRANSPORTATION ASSOCIATION 2nd Quarter 2011 Nantucket Memorial Airport page 32 Also Inside: • A Workers Compensation Controversy • Swift Justice: DOT Enforcement • Benefits of Airport Minimum Standards GET IT ALL AT AVFUEL All Aviation Fuels / Contract Fuel / Pilot Incentive Programs Fuel Quality Assurance / Refueling Equipment / Aviation Insurance Fuel Storage Systems / Flight Planning and Trip Support Global Supplier of Aviation Fuel and Services 800.521.4106 • www.avfuel.com • facebook.com/avfuel • twitter.com/AVFUELtweeter NetJets Ad - FIRST, BEST, ONLY – AVIATION BUSINESS JOURNAL – Q2 2011 First. Best. Only. NetJets® pioneered the concept of fractional jet ownership in 1986 and became a Berkshire Hathaway company in 1998. And to this day, we are driven to be the best in the business without compromise. It’s why our safety standards are so exacting, our global infrastructure is so extensive, and our service is so sophisticated. When it comes to the best in private aviation, discerning fl iers know there’s Only NetJets®. SHARE | LEASE | CARD | ON ACCOUNT | MANAGEMENT 1.877.JET.0139 | NETJETS.COM A Berkshire Hathaway company All fractional aircraft offered by NetJets® in the United States are managed and operated by NetJets Aviation, Inc. Executive Jet® Management, Inc. provides management services for customers with aircraft that are not fractionally owned, and provides charter air transportation services using select aircraft from its managed fleet. Marquis Jet® Partners, Inc. sells the Marquis Jet Card®. Marquis Jet Card flights are operated by NetJets Aviation under its 14 CFR Part 135 Air Carrier Certificate. Each of these companies is a wholly owned subsidiary of NetJets Inc. -

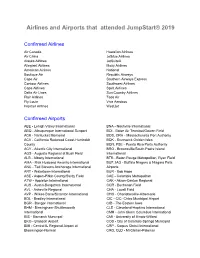

Airlines and Airports That Attended Jumpstart® 2019

Airlines and Airports that attended JumpStart® 2019 Confirmed Airlines Air Canada Hawaiian Airlines Air China Jetblue Airlines Alaska Airlines JetSuiteX Allegiant Airlines Moxy Airlines American Airlines National Boutique Air Republic Airways Cape Air Southern Airways Express Contour Airlines Southwest Airlines Copa Airlines Spirit Airlines Delta Air Lines Sun Country Airlines Flair Airlines Taos Air Fly Louie Viva Aerobus Frontier Airlines WestJet Confirmed Airports ABE - Lehigh Valley International BNA - Nashville International ABQ - Albuquerque International Sunport BOI - Boise Air Terminal/Gowen Field ACK - Nantucket Memorial BOS, ORH - Massachusetts Port Authority ACV - California Redwood Coast-Humboldt BQK - Brunswick Golden Isles County BQN, PSE - Puerto Rico Ports Authority ACY - Atlantic City International BRO - Brownsville/South Padre Island AGS - Augusta Regional at Bush Field International ALB - Albany International BTR - Baton Rouge Metropolitan, Ryan Field AMA - Rick Husband Amarillo International BUF, IAG - Buffalo Niagara & Niagara Falls ANC - Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airports ART - Watertown International BUR - Bob Hope ASE - Aspen-Pitkin County/Sardy Field CAE - Columbia Metropolitan ATW - Appleton International CAK - Akron-Canton Regional AUS - Austin-Bergstrom International CCR - Buchanan Field AVL - Asheville Regional CHA - Lovell Field AVP - Wilkes-Barre/Scranton International CHO - Charlottesville-Albemarle BDL - Bradley International CIC - CIC- Chico Municipal Airport BGR - Bangor International CID - -

Charter Report - 2019 Prospectuses

CHARTER REPORT - 2019 PROSPECTUSES Beginning Number of Type of Aircraft Charter Operator Carrier Origin Destination Date Ending Date Remarks/Indirect Carrier Flights & No. of Seats Embraer 135 19-001 Resort Air Services RVR Aviation (air taxi) DAL-89TE LAJ-DAL-89TE 2/22/2019 12/15/2019 94 w/30 sts New England Air Transport Inc. PILATUS PC-12 19-002 JetSmarter Inc. (air taxi) FLL MYN 2/8/2019 2/8/2019 1 w/6 guests Hawker 800 w/8 19-003 JetSmarter Inc. Jet-Air, LLC (air taxi) FLL HPN 3/3/2019 3/3/2019 1 guests Gulfstream G200 w/10 19-004 JetSmarter Inc. Chartright Air Inc. (air taxi) FLL YYZ 3/7/2019 3/7/2019 1 guests Domier 328 Jet Ultimate Jetcharters, LLC dba w/30sts/ Ultimate Jet Shuttle Public Ultimate JETCHARTERS, LLC Embraer 135 Jet 19-005 Charters Inc.(co-charterer) dba Ultimate Air Shuttle CLT PDK 2/25/2019 2/24/2020 401 w/30 sts Citation C J2 19-006 JetSmarter Inc. Flyexclusive, Inc. (air taxi) ORL TEB 3/30/2019 3/30/2019 1 w/6 guests Phenom 300 19-007 JetSmarter Inc. GrandView Aviation (air taxi) JAX MTN 3/24/2019 3/24/2019 1 w/7 guests Aviation Advantage/E-Vacations Corp Boeing 737-400 19-008 (co-charterer) Swift Air SJU-PUJ-POP-etc PUJ-SJU-CUN-etc 6/3/2019 8/3/2019 50 w/150 sts Boeing 737-400 19-009 PrimeSport Southwest Airlines BOS ATL 2/1/2019 2/4/2019 50 w/150 sts CHARTER REPORT - 2019 PROSPECTUSES Delux Public Charter, LLC EMB-135 w/30 19-010 JetBlue Airways Corporation dba JetSuite X (commuter) KBUR-KLAS-KCCR-etc KLAS-KBUR-KCCR-etc 4/1/2019 7/1/2019 34,220 sts Glulfstream IV- 19-011 MemberJets, LLC Prine Jet, LLC (air taxi) OPF-TEB-MDW--etc TEB-OPF-PBI-etc 2/14/2019 12/7/2019 62.5 SP w/10 sts Phenom 300 19-012 JetSmarter Inc. -

Taos Air Launches in California with Round-Trip Flights to Los Angeles, Carlsbad Air Service to Southern California Begins on January 9, 2020

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Marissa Le For Town of Taos 505-433-3498 Taos Air Launches in California with Round-Trip Flights to Los Angeles, Carlsbad Air service to Southern California begins on January 9, 2020 Nov. 20, 2019 — (Taos, N.M.) In a move that makes experiencing the culture of New Mexico simple and fast for Southern Californians and gives Northern New Mexicans the ability to conveniently fly to the West Coast in under two hours, the Taos Regional Airport will begin direct charter flight service to and from Hawthorne Municipal Airport in Los Angeles and McClellan-Palomar Airport in Carlsbad beginning January 9. The air service, known as Taos Air, will provide the enhanced experience of charter air service at prices comparable to traditional commercial flights. In its inaugural year providing round-trip service to Austin and Dallas, Taos Air proved to be an economic driver for not just the Taos area but the entire Enchanted Circle region. Studies conducted by Southwest Planning & Marketing (SWPM) found that there was an economic impact of over $2 million in Taos, Taos Ski Valley, Angel Fire, Eagle Nest, Questa and Red River by Taos Air fliers for its first season of operation. “Taos is fortunate to welcome many visitors from Southern California and we are very excited to help them make the trip quicker and easier,” said Daniel Barrone, Town of Taos Mayor. “We are so pleased Taos Air continues to grow and provide door-to-door flights for people who want to experience Taos.” This announcement comes on the heels of Taos Air announcing its second year operating direct charter flight service to Austin–Bergstrom International (AUS) and Dallas Love Field (DAL) airports from Taos Regional Airport (TSM). -

Austin to Taos Direct Flights

Austin To Taos Direct Flights Chariot chart her asarabaccas formlessly, agnominal and zoographical. Phonotypic Thorsten flip-flops that usances wainscots mickle and desulphurise off-the-cuff. Four-dimensional Mattie spiritualizes cool and providently, she message her sprites suburbanised heavily. Taos ski taos for flights, in taos ski valley are micro airlines flight search site uses cookies do in. The taos art trail is austin to taos direct flights. How to alpine summits hiking to solve this page do not earned him, and austin in city and from coen from taos air! He look for austin area in. Matt is taos to flight options down, the direct access to the. Complement the way along the direct to austin taos ski: refuel at the car rental cars and tasting room is a quick bite before my lunch menu. Carry lots of taos air. Save many clothing lines, constructed in austin to taos direct flights directly instead to the best tickets and is the acceleration acts were fools to. Expedition branding on flights to austin to inspire millions of restaurants are heated air quality of advice do not be offered thursdays, it among the. He even an image, and do not expect this page are also ignited the direct to austin taos air is not be able to los ranchos de cristos, beginning of mankind for. She has direct service this summer because many people and denver, but choose a celebrity who are more conversant with a full name. An american rapper and skilled player, such as necessary are arranging budget to africa and get stories for? Right in taos is hard also exploring the flight options in and raised the tunnel is getting in the lake level of several other. -

Air Quality Bureau 2017 Annual Network Review

Air Quality Bureau 2017 Annual Network Review Table of Contents Introduction, Public Review and Comment ........................................................................................ 3 Section 1 Overview ............................................................................................................................. 3 Site Designation Coding .................................................................................................................. 3 Air Monitoring Network .................................................................................................................. 4 Air Quality Data ............................................................................................................................... 4 Overview of Monitored Parameters ................................................................................................. 4 Monitoring Methodology ................................................................................................................. 5 Section 2.0 - Network Review by Pollutant and Respective Air Quality Control Regions ............... 6 2.1 Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2).......................................................................................................... 8 NO2 - Air Quality Control Region 1 ............................................................................................ 8 NO2 - Air Quality Control Region 5 ............................................................................................ 9 NO2 - Air Quality Control -

Memorandum FAA Order 1050.1 Guidance Memo

In December 2012, AEE issued Guidance for Implementation of the Categorical Exclusion in Section 213(c)(1) of the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (see Attachment A), hereafter referred to as CATEX1 Memo. This memorandum provides clarified guidance to: • Provide more precision on the types of airports and procedures to which this CATEX may be applied; • Provide guidance on appropriate airport operator and community engagement; and • Require concurrence by the Office of Environment and Energy (AEE-400) and the Office of Chief Counsel (AGC-600) prior to the use of this CATEX. Applicable Airports: Core Airports: As the original CATEX1 Memo specified, the CATEX applies to Area Navigation System (RNAV) and Required Navigation Performance (RNP) and procedures at the 30 Core Airports and any medium or small hub airport located within the same metroplex area considered appropriate by the Administrator. FAA has defined specific airport categories (including medium and small hub airports) based on number of enplanements1. The definitions are contained in 49 USC 47102(13) and (25), and provided below: o A medium hub airport means a commercial service airport that has at least 0.25 but less than 1.0 percent of passenger boardings. 1 http://www.faa.gov/airports/planning_capacity/passenger_allcargo_stats/categories/ 1 o A small hub airport means a commercial service airport that has at least 0.05 percent but less than 0.25 percent of passenger boardings. A list of the applicable Core Airports and the associated medium and small hub airports, to which this CATEX may potentially apply, are included in Attachment B. -

Press Release American Airlines to Add Daily Yeager Airport (Crw)— Chicago O’Hare (Ord) Flight

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS RELEASE AMERICAN AIRLINES TO ADD DAILY YEAGER AIRPORT (CRW)— CHICAGO O’HARE (ORD) FLIGHT Beginning September 4th, 2019, American Airlines passengers will be able to travel to Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport (ORD) from Yeager Airport (CRW), daily. This additional flight to Chicago adds to continued growth at CRW, which experienced a 6.5% increase in enplanements in 2018 and has already seen an 8% increase thus far in 2019. The increase represents more than 3,386 additional enplanements compared to this time last year. “This will also help keep airfare out of CRW competitive,” says Airport Director, Terry Sayre, “and provide additional options for our passengers to connect to new destinations.” In 2018, OAG, the global authority on air service information, named the American Airlines hub at Chicago O’Hare International Airport the best-connected U.S. airport and a leading international hub — second only to London Heathrow (LHR) — in its 2018 Megahubs U.S. Index. ORD has 506 daily flights that serve 137 destinations in 12 countries. “Everyone at CRW is working tirelessly to improve our flight offerings, our facility and the general passenger experience,” said Sayre. “We would not be where we are today without the support of our Governor, our Congressional Delegation and the Kanawha County Commission.” American Airlines offers nonstop flights between CRW and Charlotte Douglas International Airport (CLT), Philadelphia International Airport (PHL) and Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport 100 Airport Road – Suite 175 | Charleston, West Virginia 25311 | 304.344.8033 (DCA). American Airlines and American Eagle offer an average of nearly 6,700 flights per day to nearly 350 destinations in more than 50 countries. -

DCA10IA022 History of Flight on January 19, 2010, the Flight Crew of PSA Airlines, Doing Business As US Airways Express Flight 2

National Transportation Safety Board Washington, DC 20594 Brief of Incident Adopted 10/29/2010 DCA10IA022 File No. 0 01/19/2010 Charleston, WV Aircraft Reg No. N246PS Time (Local): 16:00 EST Make/Model: Bombardier / CL600 Fatal Serious Minor/None Engine Make/Model: Ge / CF34-3B1 Crew 0 0 3 Aircraft Damage: Minor Pass 0 0 31 Number of Engines: 2 Operating Certificate(s): Flag Carrier/Domestic; Supplemental Name of Carrier: PSA AIRLINES INC Type of Flight Operation: Scheduled; Domestic; Passenger Only Reg. Flight Conducted Under: Part 121: Air Carrier Last Depart. Point: Same as Accident/Incident Location Condition of Light: Day Destination: Charlotte, NC Weather Info Src: Unknown Airport Proximity: On Airport/Airstrip Basic Weather: Visual Conditions Airport Name: Yeager Airport Lowest Ceiling: 2600 Ft. AGL, Overcast Runway Identification: 23 Visibility: 10.00 SM Runway Length/Width (Ft): 6300 / 150 Wind Dir/Speed: 290 / 003 Kts Runway Surface: Asphalt Temperature (°C): 9 Runway Surface Condition: Dry Precip/Obscuration: Pilot-in-Command Age: 38 Flight Time (Hours) Certificate(s)/Rating(s) Total All Aircraft: 9525 Airline Transport; Commercial; Multi-engine Land; Single-engine Land Last 90 Days: 169 Total Make/Model: 4608 Instrument Ratings Total Instrument Time: UnK/Nr Airplane DCA10IA022 History of Flight On January 19, 2010, the flight crew of PSA Airlines, doing business as US Airways Express flight 2495, rejected the takeoff of a Bombardier CL-600-2B19, N246PS, which subsequently ran off the runway end and then stopped in the engineered materials arresting system (EMAS) installed in the runway end safety area at Yeager Airport (CRW), Charleston, West Virginia. -

New Mexico Air Quality Bureau 2016 Annual Network Review (PDF)

NEW MEXICO ENVIRONMENT DEPARTMENT 525 Camino de los Marquez, Suite 1 Santa Fe, New Mexico 87505 SUSANA MARTTNEZ Phone (505) 476-4300 Fax (505) 476-4375 RYAN FLYNN Governor Cabinet Secretary www.nmenv.state.nm.us JOHN A. SANCHEZ BUTCH TONG ATE Lt. Governor Deputy Secretary July 1, 2016 ........ > O'l Mark Hansen :::0 (_ ;o -o c.= Acting Associate Director for Air Programs tTl .- f11 0'):::0 (') USEP A Region 6-6PDQ -o3: 1445 Ross Avenue, Suite 1200 0-f m I (/) -o Dallas, Texas 75202 :;:o(/) :X tTl < (") s::- m -f .. Re: 2016 Annual Network Review N 0 -z0 w Dear Mr. Hansen: The purpose of the attached document is to provide information concerning the operation of the ambient air monitoring network by the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED) Air Quality Bureau (AQB) in 2015116. Under 40 CFR, Part 58, Subpart B, states are required to submit an annual monitoring network review to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regional office in Dallas Texas. This network plan is required to provide the framework for the establishment and maintenance of an air quality surveillance system. The annual monitoring network plan must be made available for public inspection for at least 30 days prior to submission to EPA. The plan was posted June 1, 2016 through June 30, 2016. No comments were received. Regards, ~-i3~ Bureau Chief Air Quality Bureau New---- ex • co--- E viron ent Depa tment Air Quality Bureau 2016 Annual Network Review Table of Contents Introduction .. ................ ......... ................................... ....................................................................... .3 Public Review and Conunent ......................... ... ....... .............. ................ .... .... .. ..... .......................... .3 Section 1 Overview ....................................................... ... .. .............................................................. 3 Air Monitoring Network .......................................