Remarks on the Actual Status of Romanian Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly March…

MAGAZINE THE DIVING BELL AND THE BUTTERFLY MARCH… “possibly Britain’s most beautiful cinema...” (BBC) MARCH 2008 Issue 36 www.therexcinema.com 01442 877759 Mon-Sat 10.30-6pm Sun 4.30-6.30pm To advertise email [email protected] WELCOME Gallery 5 March Evenings 9-17 Coming Soon 18 March Films at a glance 18 March Matinees 19-26 Dear Mrs Trellis 29, 31 SEAT PRICES: Circle £7.00 Concessions £5.50 At Table £9.00 Concessions £7.50 Royal Box (seats 6) £11.00 or for the Box £60.00 BOX OFFICE: 01442 877759 Mon to Sat 10.30 – 6.00 Sun 4.30 – 6.30 (Credit/Debit card booking fee 50p) Disabled and flat access: through the gate on High Street (right of apartments) First moon over Holliday St. Jan 2008 Some of the girls and boys you see at the Box Office and Bar: THE RECEIVING OF CHEESE… ’ve been asked to mention this on behalf of the ushers. If expectant of Rosie Abbott Linda Moss Henry Beardshaw Louise Ormiston cheese, please be alert when you see plates approaching, especially in Julia Childs Izzi Robinson the dark and particularly upstairs. Lindsey Davies I Georgia Rose Of late there have been some tragic incidents of cheese. Some has been Holly Gilbert Diya Sagar Becky Ginn Miranda Samson delivered into the wrong hands, leaving those awaiting the presence of Tom Glasser Tina Thorpe cheese bereft and likely to fidget. Beth Hannaway Olivia Wilson If you are guilty of ‘wrong hands’ cheese please own up immediately and Luke Karmali Calum Wood Jo Littlejohn Keymea Yazdanian report to cheddar monitor Adolf. -

Berkeley Art Museum·Pacific Film Archive W in Ter 20 19

WINTER 2019–20 WINTER BERKELEY ART MUSEUM · PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PROGRAM GUIDE ROSIE LEE TOMPKINS RON NAGLE EDIE FAKE TAISO YOSHITOSHI GEOGRAPHIES OF CALIFORNIA AGNÈS VARDA FEDERICO FELLINI DAVID LYNCH ABBAS KIAROSTAMI J. HOBERMAN ROMANIAN CINEMA DOCUMENTARY VOICES OUT OF THE VAULT 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 CALENDAR DEC 11/WED 22/SUN 10/FRI 7:00 Full: Strange Connections P. 4 1:00 Christ Stopped at Eboli P. 21 6:30 Blue Velvet LYNCH P. 26 1/SUN 7:00 The King of Comedy 7:00 Full: Howl & Beat P. 4 Introduction & book signing by 25/WED 2:00 Guided Tour: Strange P. 5 J. Hoberman AFTERIMAGE P. 17 BAMPFA Closed 11/SAT 4:30 Five Dedicated to Ozu Lands of Promise and Peril: 11:30, 1:00 Great Cosmic Eyes Introduction by Donna Geographies of California opens P. 11 26/THU GALLERY + STUDIO P. 7 Honarpisheh KIAROSTAMI P. 16 12:00 Fanny and Alexander P. 21 1:30 The Tiger of Eschnapur P. 25 7:00 Amazing Grace P. 14 12/THU 7:00 Varda by Agnès VARDA P. 22 3:00 Guts ROUNDTABLE READING P. 7 7:00 River’s Edge 2/MON Introduction by J. Hoberman 3:45 The Indian Tomb P. 25 27/FRI 6:30 Art, Health, and Equity in the City AFTERIMAGE P. 17 6:00 Cléo from 5 to 7 VARDA P. 23 2:00 Tokyo Twilight P. 15 of Richmond ARTS + DESIGN P. 5 8:00 Eraserhead LYNCH P. 26 13/FRI 5:00 Amazing Grace P. -

Sergei Loznitsa

IN THE FOG (V Tumane) a film by Sergei Loznitsa FIPRESCI Award Cannes 2012 Golden Apricot, Yerevan Film Festival Best Film, Odessa International Film Festival Grand Prix, Andrei Tarkovsky International Film Festival Germany / Russia / Latvia / Belarus 2012 / 128 min / Russian with English subtitles / Certificate TBC Release date: April 26th 2013 FOR ALL PRESS ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Sue Porter/Lizzie Frith – Porter Frith Ltd Tel: 020 7833 8444/E‐mail: [email protected] FOR ALL OTHER ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Robert Beeson – New Wave Films [email protected] 10 Margaret Street London W1W 8RL Tel: 020 3178 7095 www.newwavefilms.co.uk SYNOPSIS Belarus on the western frontiers of the USSR 1942. The region is under German occupation and local partisans are fighting a brutal resistance campaign. A train is derailed not far from the village, where Sushenya, a rail worker, lives with his family. Innocent Sushenya is arrested with a group of saboteurs, but the German officer makes a decision not to hang him with the others and sets him free. Rumours of Sushenya’s treason spread quickly and partisans Burov and Voitik arrive from the forest to get revenge. As the partisans lead their victim through the forest, they are ambushed, and Sushenya finds himself one‐to‐one with his wounded enemy. Deep in an ancient forest, where there are neither friends nor enemies and where the line between treason and heroism disappears, Sushenya is forced to make a moral choice under immoral circumstances. More details and downloads at www.newwavefilms.co.uk -

Adjective. POLICE

A FILM BY CORNELIU PORUMBOIU POLICE, adjective. WITH THE SUPPORT WITH THE PARTICIPATION OF ROMANIAN C.N.C OF HBO ROMANIA SYNOPSIS & CONTACT Cristi is a policeman who refuses to arrest a young man who offers PRESS AGENTS hashish to two of his school mates. "Offering" is punished by the FRANCOIS HASSAN GUERRAR law. Cristi believes that the law will change, he does not want the AND CHARLOTTE TOURRET life of a young man he considers irresponsible to be a burden on his conscience. For his superior the word conscience has a totally IN CANNES different meaning… Appart JUNES 131, D’Antibes Str., 06400 CANNES Tel.: +33 1 43 59 48 02 [email protected] ABSOLUMENT 12 Lamartine Str. - 75009 Paris Tel.: +33 1 43 59 4 8 02 Fax : +33 1 43 59 48 05 [email protected] SALES AGENT COACH 14 IN CANNES 17, Mérimée Square, 2nd Floor (in front of the Palais) 06400 Cannes Tel.: +33 4 93 68 43 34 Fax: +33 4 93 68 45 36 From 13th to 24th of May Jaume Domenech, Cell: +34 6 52 93 40 92 [email protected] Pape Boye, Cell: +33 6 19 96 17 07 [email protected] COACH 14 IN PARIS 21, Jean-Pierre Timbaud Str. 75011 Paris Tel. : +33 1 47 00 10 60 Fax : +33 1 47 00 10 02 COACH 14 IN BARCELONA 36 Mandri 08022 Barcelona Tel. : +34 93 280 57 52 Fax: +34 93 205 08 55 CREW LIST Director - Corneliu Porumboiu Executive producer - Marcela Ursu Script-Corneliu Porumboiu Director of Photography - Marius Panduru Art Director - Mihaela Poenaru Edit - Roxana Szel Costumes - Giorgiana Bostan Sound - Alexandru Dragomir et Sebastian Zsemlye 113min 35mm 1:1,85 COLOR DOLBY DIGITAL 2009 1 Assistant Director - Mihai Sofronea , , DIRECTOR S DIRECTOR S NOTES INTERVIEW CORNELIU PORUMBOIU TALKS ABOUT HIS NEW FILM POLICE, adjective. -

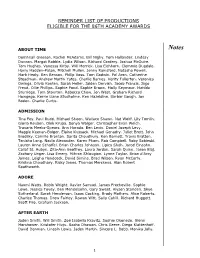

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 86Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 86TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT TIME Notes Domhnall Gleeson. Rachel McAdams. Bill Nighy. Tom Hollander. Lindsay Duncan. Margot Robbie. Lydia Wilson. Richard Cordery. Joshua McGuire. Tom Hughes. Vanessa Kirby. Will Merrick. Lisa Eichhorn. Clemmie Dugdale. Harry Hadden-Paton. Mitchell Mullen. Jenny Rainsford. Natasha Powell. Mark Healy. Ben Benson. Philip Voss. Tom Godwin. Pal Aron. Catherine Steadman. Andrew Martin Yates. Charlie Barnes. Verity Fullerton. Veronica Owings. Olivia Konten. Sarah Heller. Jaiden Dervish. Jacob Francis. Jago Freud. Ollie Phillips. Sophie Pond. Sophie Brown. Molly Seymour. Matilda Sturridge. Tom Stourton. Rebecca Chew. Jon West. Graham Richard Howgego. Kerrie Liane Studholme. Ken Hazeldine. Barbar Gough. Jon Boden. Charlie Curtis. ADMISSION Tina Fey. Paul Rudd. Michael Sheen. Wallace Shawn. Nat Wolff. Lily Tomlin. Gloria Reuben. Olek Krupa. Sonya Walger. Christopher Evan Welch. Travaris Meeks-Spears. Ann Harada. Ben Levin. Daniel Joseph Levy. Maggie Keenan-Bolger. Elaine Kussack. Michael Genadry. Juliet Brett. John Brodsky. Camille Branton. Sarita Choudhury. Ken Barnett. Travis Bratten. Tanisha Long. Nadia Alexander. Karen Pham. Rob Campbell. Roby Sobieski. Lauren Anne Schaffel. Brian Charles Johnson. Lipica Shah. Jarod Einsohn. Caliaf St. Aubyn. Zita-Ann Geoffroy. Laura Jordan. Sarah Quinn. Jason Blaj. Zachary Unger. Lisa Emery. Mihran Shlougian. Lynne Taylor. Brian d'Arcy James. Leigha Handcock. David Simins. Brad Wilson. Ryan McCarty. Krishna Choudhary. Ricky Jones. Thomas Merckens. Alan Robert Southworth. ADORE Naomi Watts. Robin Wright. Xavier Samuel. James Frecheville. Sophie Lowe. Jessica Tovey. Ben Mendelsohn. Gary Sweet. Alyson Standen. Skye Sutherland. Sarah Henderson. Isaac Cocking. Brody Mathers. Alice Roberts. Charlee Thomas. Drew Fairley. Rowan Witt. Sally Cahill. -

Neuerwerbungen Noten

NEUERWERBUNGSLISTE NOVEMBER 2019 FILM Medienempfehlungen der Cinemathek in der Amerika-Gedenkbibliothek © Eva Kietzmann, ZLB Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin Stiftung des öffentlichen Rechts Inhaltsverzeichnis Film 5 Stummfilme 3 Film 7 Fernsehserien 3 Film 10 Tonspielfilme 4 Film 20 Animationsfilme 7 Film 30 Experimentalfilme 7 Musi Musikdarbietungen/ Musikvideos 8 K 400 Kinderfilme 9 Ju 400 Jugendfilme 10 Sachfilme nach Fachgebiet 11 Seite 2 von 14 Stand vom: 01.12.2019 Neuerwerbungen im Fachbereich Film Film 5 Stummfilme Film 5/20:3.DVD Retour de flamme : [DVD-Video]. - 3. Retour de flamme 3 : une séance de ci- nématographe ; [DVD Video mit Movietext] / Charles Parrott [Regie] ; Aurelio Rossi [Regie] ; Dave Fleischer [Regie] ; Max Fleischer [Regie] ; Alfred Machin [Regie] ; Gilles Margaritis [Regie] ; Tex Avery [Regie] ; Fred Newmeyer [Regie] ; Samuel Taylor [Regie] ; Willi Wolff [Regie] ; Hal Roach [Prod.] ; Pierre Braun- berger [Prod.] ; Harry Pollard [Darst.] ; Harold Lloyd [Darst.] ; Mildred Davis [Darst.] ; Django Reinhardt [Darst.] ; Stéphane Grappelly [Darst.] ; Ellen Richter [Darst.] ; Anton Pointner [Darst.] .... - [ca. 2005] Film 7 Fernsehserien Film 7 ArneDah Arne Dahl. - 3. Vol. 3 / Lisa Farzaneh Regie ; Lars Blomgren Produzent/in ; Mag- 1:3.BD nus Samuelsson Schauspieler/in ; Natalie Minnevik Schauspieler/in. - 2016 Film 7 ChaShad Chasing shadows / Christopher Menaul [Regie] ; Rob Williams [Drehbuchau- 1:DVD tor/in] ; Tony Slater-Ling [Kamera] ; Samuel Sim [Komponist/in] ; Reece Shearsmith [Schauspieler/in] ; Alex Kingston [Schauspieler/in] ; Noel Clarke [Schauspieler/in]. - 2014 Film 7 CodeKil Code of a killer : murder is in the blood / James Strong [Regie] ; Michael Cromp- 1:DVD ton [Drehbuchautor/in] ; Matt Gray [Kamera] ; Glenn Gregory [Komponist/in] ; David Threlfall [Schauspieler/in] ; John Simm [Schauspieler/in] ; Lorcan Cranitch [Schauspieler/in]. -

Films in Competition and Parallel Sections

Marrakech Unveils Its Official Selection: Films in Competition and Parallel Sections • 14 films in Official Competition • 7 Moroccan films screened in the framework of a dedicated section • The 11th Continent, a new section to discover sharp and bold cinema • Gala screenings, Special Screenings, and general public screenings round out the programme Rabat, November 14, 2018, the Marrakech International Film Festival (FIFM) unveils the official selection. From November 30 to December 8, 2018, festival-goers and cinema-lovers alike will discover no fewer than 80 films coming from 29 different countries. The line-up is divided into several sections, the main ones including the Official Competition; Gala Screenings; Special Screenings; The 11th Continent; Moroccan Panorama; Jamaa El-Fna Square Screenings; Audio-described Cinema; and a Tribute section. Fourteen (14) films are thus in the running to win the Marrakech Etoile d’Or (or, the Gold Star), in the framework of the Official Competition of the 17th Edition of FIFM. In selecting these first or second feature-length films, the Festival grants priority to the discovery and consecration of new talents in world cinema. The selection is eclectic, its purpose being to showcase several cinematic universes developed in different regions of the world, with four (4) European films (from Austria, Bulgaria, Germany, and Serbia); three (3) films from Latin America (Argentina and Mexico); one (1) US film; two (2) Asian films (China and Japan); and four (4) films from the MENA region (Egypt, Morocco, Sudan, and Tunisia). Of the 14 films in competition, six are directed by women. Six great auteur films, with first-rate distribution, will be shown on the Festival’s gala evenings. -

GSC Films: S-Z

GSC Films: S-Z Saboteur 1942 Alfred Hitchcock 3.0 Robert Cummings, Patricia Lane as not so charismatic love interest, Otto Kruger as rather dull villain (although something of prefigure of James Mason’s very suave villain in ‘NNW’), Norman Lloyd who makes impression as rather melancholy saboteur, especially when he is hanging by his sleeve in Statue of Liberty sequence. One of lesser Hitchcock products, done on loan out from Selznick for Universal. Suffers from lackluster cast (Cummings does not have acting weight to make us care for his character or to make us believe that he is going to all that trouble to find the real saboteur), and an often inconsistent story line that provides opportunity for interesting set pieces – the circus freaks, the high society fund-raising dance; and of course the final famous Statue of Liberty sequence (vertigo impression with the two characters perched high on the finger of the statue, the suspense generated by the slow tearing of the sleeve seam, and the scary fall when the sleeve tears off – Lloyd rotating slowly and screaming as he recedes from Cummings’ view). Many scenes are obviously done on the cheap – anything with the trucks, the home of Kruger, riding a taxi through New York. Some of the scenes are very flat – the kindly blind hermit (riff on the hermit in ‘Frankenstein?’), Kruger’s affection for his grandchild around the swimming pool in his Highway 395 ranch home, the meeting with the bad guys in the Soda City scene next to Hoover Dam. The encounter with the circus freaks (Siamese twins who don’t get along, the bearded lady whose beard is in curlers, the militaristic midget who wants to turn the couple in, etc.) is amusing and piquant (perhaps the scene was written by Dorothy Parker?), but it doesn’t seem to relate to anything. -

57Th New York Film Festival September 27- October 13, 2019

57th New York Film Festival September 27- October 13, 2019 filmlinc.org AT ATTHE THE 57 57TH NEWTH NEW YORK YORK FILM FILM FESTIVAL FESTIVAL AndAnd over over 40 40 more more NYFF NYFF alums alums for for your your digitaldigital viewing viewing pleasure pleasure on onthe the new new KINONOW.COM/NYFFKINONOW.COM/NYFF Table of Contents Ticket Information 2 Venue Information 3 Welcome 4 New York Film Festival Programmers 6 Main Slate 7 Talks 24 Spotlight on Documentary 28 Revivals 36 Special Events 44 Retrospective: The ASC at 100 48 Shorts 58 Projections 64 Convergence 76 Artist Initiatives 82 Film at Lincoln Center Board & Staff 84 Sponsors 88 Schedule 89 SHARE YOUR FESTIVAL EXPERIENCE Tag us in your posts with #NYFF filmlinc.org @FilmLinc and @TheNYFF /nyfilmfest /filmlinc Sign up for the latest NYFF news and ticket updates at filmlinc.org/news Ticket Information How to Buy Tickets Online filmlinc.org In Person Advance tickets are available exclusively at the Alice Tully Hall box office: Mon-Sat, 10am to 6pm • Sun, 12pm to 6pm Day-of tickets must be purchased at the corresponding venue’s box office. Ticket Prices Main Slate, Spotlight on Documentary, Special Events*, On Cinema Talks $25 Member & Student • $30 Public *Joker: $40 Member & Student • $50 Public Directors Dialogues, Master Class, Projections, Retrospective, Revivals, Shorts $12 Member & Student • $17 Public Convergence Programs One, Two, Three: $7 Member & Student • $10 Public The Raven: $70 Member & Student • $85 Public Gala Evenings Opening Night, ATH: $85 Member & Student • $120 Public Closing Night & Centerpiece, ATH: $60 Member & Student • $80 Public Non-ATH Venues: $35 Member & Student • $40 Public Projections All-Access Pass $140 Free Events NYFF Live Talks, American Trial: The Eric Garner Story, Holy Night All free talks are subject to availability. -

Manufacturing Mystery

WHAT’S ON — Film Manufacturing mystery Editor’s Choice The auteurs behind three of this month’s new releases revel in keeping the viewer on the back foot. By Paul O’Callaghan DON’T MISS KuirFest Berlin or its first half or so, High Life While Denis’ film is challenging by Happily, there’s one confounding Conceived to (photo), the English-language multiplex standards, it looks like a arthouse drama out this month that protest the ‘indefinite ban’ on F debut by French auteur Claire Marvel movie next to Sunset, László totally sticks the landing. Adapted LGBTQ+ events Denis, is an assured piece of enig- Nemes’ follow-up to his Oscar-win- from a Haruki Murakami short in Ankara, this fest matic nonlinear storytelling. It stars ning Holocaust drama Son of Saul. story, Lee Chang-dong’s Burning kicked off in May but concludes Robert Pattinson as Monte, a taci- Set in Budapest on the eve of World centres around Jong-su (Yoo Ah-in), with a screening turn father raising his baby daughter War I, it follows the determined Írisz an aspiring writer from the sticks of Lizzie Borden’s in testing circumstances – the pair (Juli Jakab) on her quest to reclaim now living in Seoul, who becomes 1983 queer-feminist classic Born in are the sole inhabitants of a dilapi- her rightful place in society, decades embroiled in a love triangle of sorts Flames at bi’bak, dated spaceship hurtling towards after her parents, the founders of a with his former classmate Hae- followed by a a black hole. -

Absurd Black Humour As Social Criticism in Contemporary European Cinema

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Absurd Black Humour as Social Criticism in Contemporary European Cinema Eszter Simor Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2019 Submitted in satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Film Studies at the University of Edinburgh This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (PhD) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non- commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. -

News Release. 2016 Toronto International Film Festival Unveils Its

July 26, 2016 .NEWS RELEASE. 2016 TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL UNVEILS ITS FIRST SLATE OF GALAS AND SPECIAL PRESENTATIONS Featuring World Premieres from filmmakers including Oliver Stone, Mira Nair, Ewan McGregor, Konkona Sensharma, Lone Scherfig, Raja Amari, Jonathan Demme, Baltasar Kormákur, Amma Asante, Christopher Guest, Feng Xiaogang, Rob Reiner, J.A. Bayona, Arnaud des Pallières, Kiyoshi Kurosawa and many more TORONTO — Piers Handling, CEO and Director of TIFF, and Cameron Bailey, Artistic Director of the Toronto International Film Festival, announced the first round of titles premiering in the Gala and Special Presentations programmes of the 41st Toronto International Film Festival®. Of the 18 Galas and 49 Special Presentations announced, this initial lineup includes films from such celebrated directors as Werner Herzog, Denis Villeneuve, Jim Jarmusch, Mia Hansen-Løve, Rebecca Zlotowski, Tom Ford, François Ozon, Andrea Arnold, Maren Ade, Park Chan-wook, Kim Jee woon, Kenneth Lonergan, Antoine Fuqua, Damien Chazelle, Pablo Larraín, and Paul Verhoeven. “Revealing the first round of films offers a highly anticipated glimpse into the Festival’s lineup this year,” said Handling. “Bold and adventuresome work by established and emerging filmmakers from Canada, France, South Africa, Ireland, the UK, Australia, USA, South Korea, Iceland, Germany, Denmark, Chile, India, and China will illuminate Toronto screens and red carpets over another remarkable 11 days this September.” “The global voices, transformative stories and diverse perspectives of these films capture the cinematic climate of today,” said Bailey. “New films featuring cinema’s brightest talents promise to captivate and entertain the world’s film community and audiences alike.” The 41st Toronto International Film Festival runs from September 8 to 18, 2016.