Edward Said and Irish Criticism Conor Mccarthy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Identity in Seamus Deane's Reading in the Dark Peter Jasinski

Inscape Volume 21 | Number 2 Article 6 10-1-2001 Irish Identity in Seamus Deane's Reading in the Dark Peter Jasinski Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/inscape Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Jasinski, Peter (2001) "Irish Identity in Seamus Deane's Reading in the Dark," Inscape: Vol. 21 : No. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/inscape/vol21/iss2/6 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inscape by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. IRISH IDENTITY IN SEAMUS DEANE'S READING IN THE DARK Peter Jasinski n Seamus Deane's Reading in the Dark, Deane presents us with the Ichildhood of an unnamed narrator who tells the story of his troubled family in postwar Northern Ireland. As the boy stumbles through the complexities and ironies of the adult world, he slowly increases in social and political awareness. The novel takes its title from a scene in which the boy, after the lights are turned off, tries to imagine the story he had been reading. The image of reading in the dark expresses the difficulty of reconstructing the past from fragmen tary accounts available in the present: the narrator's family history "came to [him] in bits, from people who rarely recognized all they had told" (236). He uncovers only a partial picture of the truth as he tries to put together the tragic, mysterious past of his family. -

Irish Divorce/Joyce's

Irish Divorce/Joyce’s Ulysses Irish Divorce/ Joyce’s Ulysses Peter Kuch Peter Kuch University of Otago Dunedin, New Zealand ISBN 978-1-349-95187-1 ISBN 978-1-137-57186-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57186-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017939123 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institu- tional affiliations. Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Nature America Inc. -

Field Day Revisited (II): an Interview with Declan Kiberd1

Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies 33.2 September 2007: 203-35 Field Day Revisited (II): An Interview with Declan Kiberd1 Yu-chen Lin National Sun Yat-sen University Abstract Intended to address the colonial crisis in Northern Ireland, the Field Day Theatre Company was one of the most influential, albeit controversial, cultural forces in Ireland in the 1980’s. The central idea for the company was a touring theatre group pivoting around Brian Friel; publications, for which Seamus Deane was responsible, were also included in its agenda. As such it was greeted by advocates as a major decolonizing project harking back to the Irish Revivals of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Its detractors, however, saw it as a reactionary entity intent on reactivating the same tired old “Irish Question.” Other than these harsh critiques, Field Day had to deal with internal divisions, which led to Friel’s resignation in 1994 and the termination of theatre productions in 1998. Meanwhile, Seamus Deane persevered with the publication enterprise under the company imprint, and planned to revive Field Day in Dublin. The general consensus, however, is that Field Day no longer exists. In view of this discrepancy, I interviewed Seamus Deane and Declan Kiberd to track the company’s present operation and attempt to negotiate among the diverse interpretations of Field Day. In Part One of this transcription, Seamus Deane provides an insider’s view of the aspirations, operation, and dilemma of Field Day, past and present. By contrast, Declan Kiberd in Part Two reconfigures Field Day as both a regional and an international movement which anticipated the peace process beginning in the mid-1990’s, and also the general ethos of self-confidence in Ireland today. -

Downloaded from Downloaded on 2020-06-06T01:34:25Z Ollscoil Na Héireann, Corcaigh

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title A cultural history of The Great Book of Ireland – Leabhar Mór na hÉireann Author(s) Lawlor, James Publication date 2020-02-01 Original citation Lawlor, J. 2020. A cultural history of The Great Book of Ireland – Leabhar Mór na hÉireann. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2020, James Lawlor. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/10128 from Downloaded on 2020-06-06T01:34:25Z Ollscoil na hÉireann, Corcaigh National University of Ireland, Cork A Cultural History of The Great Book of Ireland – Leabhar Mór na hÉireann Thesis presented by James Lawlor, BA, MA Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College Cork The School of English Head of School: Prof. Lee Jenkins Supervisors: Prof. Claire Connolly and Prof. Alex Davis. 2020 2 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 4 Declaration .......................................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ 6 List of abbreviations used ................................................................................................... 7 A Note on The Great -

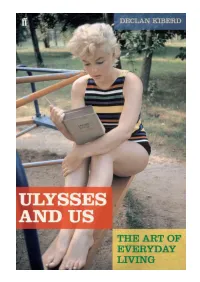

Ulysses and Us

Ulysses and Us The Art of Everyday Living declan kiberd First published in 2009 by Faber and Faber Ltd Bloomsbury House 74–77 Great Russell Street London wc1b 3da Typeset by Faber and Faber Ltd Printed in England by CPI Mackays, Chatham All rights reserved © Declan Kiberd, 2009 The right of Declan Kiberd to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 978–0–571–24254–2 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 In memory of John McGahern ‘Níl ann ach lá dár saol’ Contents Acknowledgements ix Note on the Text xi How Ulysses Didn’t Change Our Lives 3 How It Might Still Do So 16 Paralysis, Self-Help and Revival 32 1 Waking 41 10 Wandering 153 2 Learning 53 11 Singing 168 3 Thinking 64 12 Drinking 181 4 Walking 77 13 Ogling 193 5 Praying 89 14 Birthing 206 6 Dying 100 15 Dreaming 222 7 Reporting 113 16 Parenting 237 8 Eating 124 17 Teaching 248 9 Reading 137 18 Loving 260 Ordinary People’s Odysseys 277 Old Testaments and New 296 Depression and After: Dante’s Comedy 313 Shakespeare, Hamlet and Company 331 Conclusion: The Long Day Fades 347 Notes 359 Index 381 vii Acknowledgements For almost thirty years the students of University College Dublin have been teaching me about their famous fore- runner. -

Seamus Deane Papers 1960-2016

DEANE, SEAMUS, 1940- Seamus Deane papers 1960-2016 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Digital Material Available in this Collection Descriptive Summary Creator: Deane, Seamus, 1940- Title: Seamus Deane papers 1960-2016 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1210 Extent: 9.75 linear feet (21 boxes) Abstract: Papers of Irish poet and educator Seamus Deane, including writings, correspondence, journals and business records Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Source Purchase, 2011. Citation [after identification of item(s)], Seamus Deane papers, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Processing Processed by Susan McDonald and Maggie Greaaves, November 2013. This finding aid may include language that is offensive or harmful. Please refer to the Rose Library's harmful language statement for more information about why such language may appear and ongoing efforts to remediate racist, ableist, sexist, homophobic, euphemistic and other oppressive language. If you are concerned about language used in this finding aid, please contact us at [email protected]. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Seamus Deane papers, 1960-2016 Manuscript Collection No. 1210 Collection Description Biographical Note Seamus Deane (1940-), Irish poet and educator, was born in Derry, Northern Ireland. He attended Queen's University, Belfast and Cambridge University. -

The IRISH Seminar 2021

The IRISH Seminar 2021 Faculty Lead: Barry McCrea Format: Webinar* Please note that all times are listed in EST. Tuesday 8 June 9am Welcome & Introductions by Patrick Griffin & Barry McCrea 9.30am-10.30am Opening Roundtable: The State of Irish History Break Panel: Carole Holohan (Trinity College Dublin) 11.00am – 12.00pm Anne Dolan (Trinity College Dublin) Enda Delaney (University of Edinburgh) Ian McBride (Hertford College, Oxford) Moderator: Patrick Griffin (Notre Dame) 2-3pm Poetry Reading: Doireann Ní Gríofa Moderator: Brian Ó Conchubhair Wednesday 9 June Irish Studies from austerity to pandemic Editors of the Routledge International Handbook of Irish Studies (2021) in conversation with selected contributors. 9.00-9.15am Introduction with Renée Fox (University of California, Santa Cruz), Mike Cronin (Boston College) and Brian Ó Conchubhair (Notre Dame) 9.15-10.00am Eric Falci (University of California, Berkeley): Aesthetics of Irish poetry Sarah Townsend (University of New Mexico): Race in Ireland & Irish America. 10.00-10.15am Break 10.15-11.00am Claire Bracken (Union College): Gender and Irish Studies Nessa Cronin (NUI Galway): Environmentalities & the Anthropocene Maggie O'Neill (NUI Galway): The Ageing body in Irish Literature 11.00-11.15am Break 11.15-12.00pm Discussion and Q&A with panellists and participants Thursday 10 June Digital Humanities & Irish Studies 9.00-9.25 Beyond 2022 project overview. 9.25-10.00 Case Study 1: Medieval Ireland by Lynn Kigallon (Trinity College Dublin) 10.00-10.30 Break 10.30-11.00 Case Study 2: Eighteenth Century Ireland by Tim Murtagh (Trinity College Dublin) 11.00-11.15 Break 11.15-12.00 Discussion Friday 11 June Black Ireland Please note times for this seminar are subject to change** 9am Introduction by Chante Mouton Kinyon (Notre Dame) 9.15am Korey Garibaldi (Notre Dame) with Colm Toibin (Columbia): Culture and Racial Cosmopolitanism 10.15am Comfort break 10.45-11.45 Chante Mouton Kinyon with Colm Tóibín: Stranger in the Village 12:00-12.30 Discussion. -

Irelands: Migration, Media, and Locality in Modern Day Dublin

Imagining Irelands: Migration, Media, and Locality in Modern Day Dublin by Aaron Christopher Thornburg Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Naomi Quinn, Supervisor ___________________________ Lee D. Baker ___________________________ Katherine P. Ewing ___________________________ John L. Jackson, Jr. ___________________________ Suzanne Shanahan Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 ABSTRACT Imagining Irelands: Migration, Media, and Locality in Modern Day Dublin by Aaron Christopher Thornburg Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Naomi Quinn, Supervisor ___________________________ Lee D. Baker ___________________________ Katherine P. Ewing ___________________________ John L. Jackson, Jr. ___________________________ Suzanne Shanahan An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Aaron Christopher Thornburg 2011 Abstract This dissertation explores the place of Irish-Gaelic language (Gaeilge) television and film media in the lives of youths living in the urban greater Dublin metropolitan area in the Republic of Ireland. By many accounts, there has been a Gaeilge renaissance underway in recent times. The number of Gaeilge-medium primary and secondary schools (Gaelscoileanna) has grown throughout the 1990s and into the twenty-first century, the year 2003 saw the passage of the Official Languages Act (laying the groundwork to assure all public services would be made available in Gaeilge as well as English), and as of January 2007 Gaeilge has become a working language of the European Union. -

In Joyce's Dubliners

PARALYSIS AS “SPIRITUAL LIBERATION” IN JOYCE’S DUBLINERS Iven Lucas Heister, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: David Holdeman, Major Professor and Chair of the Department of English Masood Raja, Committee Member Stephanie Hawkins, Committee Member Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Heister, Iven Lucas. Paralysis as “spiritual liberation” in Joyce’s Dubliners. Master of Arts (English), May 2014, 50 pp., references, 26 titles. In James Joyce criticism, and by implication Irish and modernist studies, the word paralysis has a very insular meaning. The word famously appears in the opening page of Dubliners, in “The Sisters,” which predated the collection’s 1914 publication by ten years, and in a letter to his publisher Grant Richards. The commonplace conception of the word is that it is a metaphor that emanates from the literal fact of the Reverend James Flynn’s physical condition the narrator recalls at the beginning of “The Sisters.” As a metaphor, paralysis has signified two immaterial, or spiritual, states: one individual or psychological and the other collective or social. The assumption is that as a collective and individual signifier, paralysis is the thing from which Ireland needs to be freed. Rather than relying on this received tradition of interpretation and assumptions about the term, I consider that paralysis is a two-sided term. I argue that paralysis is a problem and a solution and that sometimes what appears to be an escape from paralysis merely reinforces its negative manifestation. Paralysis cannot be avoided. Rather, it is something that should be engaged and used to redefine individual and social states. -

Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies Speakers and Public Talks Series Fall 2015

KEOUGH-NAUGHTON INSTITUTE FOR IRISH STUDIES SPEAKERS AND PUBLIC TALKS SERIES FALL 2015 Cycle Race – 126-Mile Championship of Ireland at Dundalk, 1953 © Irish Photo Archive www.irishphotoarchive.ie SEPTEMBER Tuesday, October 6th Saturday, November 14th 4:00 p.m. DeBartolo Performing Arts Center, Patricia 12:00 p.m. Annenberg Auditorium, Friday, September 4th George Decio Theatre Snite Museum of Art 4:00 p.m. Hesburgh Library, Reading: Barry McGovern Reads Joyce and Beckett Arts and Letters Saturday Scholars Series: Rare Books and Special Collections Barry McGovern, Actor, 1916: Screening the Irish Rebellion Seamus Heaney Memorial Lecture: Naughton Distinguished Visiting Faculty Fellow, Bríona Nic Dhiarmada, University of Notre Dame Heaney, Place and Property Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies Christopher Morash, Trinity College Dublin Friday, November 20th Friday, October 30th 9:00 a.m. Boston Marriott Copley Place, Salon C-D Friday, September 11th 3:30 p.m. 424 Flanner Hall Shamrock Series Event: 5:00 p.m. McKenna Hall Auditorium Joyce’s Empathy Irish in America: Immigration, Religion and Politics Hibernian Lecture: Blood Runs Green: Joseph Buttigieg, University of Notre Dame John McGreevy, Christopher Fox, Bríona Nic The Murder that Transfixed Gilded Age Chicago Dhiarmada, Patrick Griffin, University of Notre Dame; Gillian O’Brien, Liverpool John Moores University Michael Cronin, Boston College Co-sponsored by the Cushwa Center for the Study of NOVEMBER American Catholicism Thursday, November 5th DECEMBER Friday, September 18th Hesburgh Library, Rare Books and Special Collections 4:00 p.m. Hesburgh Library, Friday, December 4th 3:00 p.m. Ian McBride, King’s College London: Rare Books and Special Collections The Meaning of the Troubles 3:30 p.m. -

2019 – 2020 English Literature Third Year Option Courses

2019 – 2020 ENGLISH LITERATURE THIRD YEAR OPTION COURSES (These courses are elective and each is worth 20 credits) Before students will be allowed to take one of the non-departmentally taught Option courses (i.e. a LLC Common course or Divinity course), they must already have chosen to do at least 40-credits worth of English or Scottish Literature courses in their Third Year. For Joint Honours students this is likely to mean doing one of their two Option courses (= 20 credits) plus two Critical Practice courses (= 10 credits each). 6 June 2019 SEMESTER ONE Page Body in Literature 3 Contemporary British Drama 6 Creative Writing: Poetry * 8 Creative Writing: Prose * [for home students] 11 Creative Writing: Prose * [for Visiting Students only] 11 Discourses of Desire: Sex, Gender, & the Sonnet Sequence . 15 Edinburgh in Fiction/Fiction in Edinburgh * [for home students] 17 Edinburgh in Fiction/Fiction in Edinburgh * [for Visiting Students only] 17 Fiction and the Gothic, 1840-1940 19 Haunted Imaginations: Scotland and the Supernatural * 21 Modernism and Empire 22 Modernism and the Market 24 Novel and the Collapse of Humanism 26 Sex and God in Victorian Poetry 28 Shakespeare’s Comedies: Identity and Illusion 30 Solid Performances: Theatricality on the Early Modern Stage 32 The Cinema of Alfred Hitchcock (=LLC Common Course) 34 The Making of Modern Fantasy 36 The Subject of Poetry: Marvell to Coleridge * 39 Working Class Representations * 41 SEMESTER TWO Page American Innocence 44 American War Fiction 47 Censorship 49 Climate Change Fiction -

RNL04-NLI Autumn 07.Indd

NEWS Donal Cam O’Sullivan Beare, Number 29: Autumn 2007 courtesy of Maynooth College. A new book, The Irish on the move in Europe, 1600–1800, to be published Winter 2007 offers an illustrated overview of the travels, travails and triumphs of thousands of Irish migrants from all walks of life – students, soldiers, merchants, aristocrats, writers, entrepreneurs, composers and even beggars – who crossed the seas to ports such as Rouen, La Coruna and Ostende from the opening decades of the 1600s onwards. This phenomenon, born of political dislocation in Ireland and the lure of a better life in Europe, would continue until the era of the French Revolution. While people, ideas and goods had always moved between Ireland and Europe, the pace quickened after the Nine Years War between the Ulster earls and Queen Elizabeth had reached its climax. The earls’ defeat at Kinsale, and their departure overseas in 1607, unleashed the first wave of Irish migration, mostly of soldiers and their dependents, to Europe. Irish merchants were key figures in moving the migrating military to the Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann Continent. Their human cargo also included ecclesiastics in search of education and better opportunities. With native ingenuity and foreign patronage they established a National Library of Ireland network of colleges that eventually extended as far east as Wielun in Poland. Together, Irish soldiers, merchants and clergy left their mark on their host societies. In The Irish on the move in Europe, 1600–1800 we catch glimpses of the Irish migrants’ NUACHT achievements in war, trade, politics and religion; we also get a taste of the more mundane side of migrant life – the constant graft for survival, the casualties of war and social conflict, the sorry fate of the weak, the poor and the sick.