A Brotherly Love Big Year

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NH Bird Records

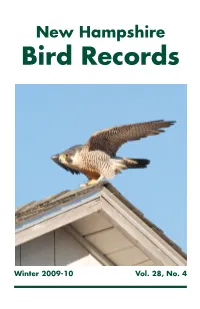

V28 No4-Winter09-10_f 8/22/10 4:45 PM Page i New Hampshire Bird Records Winter 2009-10 Vol. 28, No. 4 V28 No4-Winter09-10_f 8/22/10 4:45 PM Page ii AUDUBON SOCIETY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE New Hampshire Bird Records Volume 28, Number 4 Winter 2009-10 Managing Editor: Rebecca Suomala 603-224-9909 X309, [email protected] Text Editor: Dan Hubbard Season Editors: Pamela Hunt, Spring; Tony Vazzano, Summer; Stephen Mirick, Fall; David Deifik, Winter Layout: Kathy McBride Assistants: Jeannine Ayer, Lynn Edwards, Margot Johnson, Susan MacLeod, Marie Nickerson, Carol Plato, William Taffe, Jean Tasker, Tony Vazzano Photo Quiz: David Donsker Photo Editor: Jon Woolf Web Master: Len Medlock Editorial Team: Phil Brown, Hank Chary, David Deifik, David Donsker, Dan Hubbard, Pam Hunt, Iain MacLeod, Len Medlock, Stephen Mirick, Robert Quinn, Rebecca Suomala, William Taffe, Lance Tanino, Tony Vazzano, Jon Woolf Cover Photo: Peregrine Falcon by Jon Woolf, 12/1/09, Hampton Beach State Park, Hampton, NH. New Hampshire Bird Records is published quarterly by New Hampshire Audubon’s Conservation Department. Bird sight- ings are submitted to NH eBird (www.ebird.org/nh) by many different observers. Records are selected for publication and not all species reported will appear in the issue. The published sightings typically represent the highlights of the season. All records are subject to review by the NH Rare Birds Committee and publication of reports here does not imply future acceptance by the Committee. Please contact the Managing Editor if you would like to report your sightings but are unable to use NH eBird. -

January 2020.Indd

BROWN PELICAN Photo by Rob Swindell at Melbourne, Florida JANUARY 2020 Editors: Jim Jablonski, Marty Ackermann, Tammy Martin, Cathy Priebe Webmistress: Arlene Lengyel January 2020 Program Tuesday, January 7, 2020, 7 p.m. Carlisle Reservation Visitor Center Gulls 101 Chuck Slusarczyk, Jr. "I'm happy to be presenting my program Gulls 101 to the good people of Black River Audubon. Gulls are notoriously difficult to identify, but I hope to at least get you looking at them a little closer. Even though I know a bit about them, I'm far from an expert in the field and there is always more to learn. The challenge is to know the particular field marks that are most important, and familiarization with the many plumage cycles helps a lot too. No one will come out of this presentation an expert, but I hope that I can at least give you an idea what to look for. At the very least, I hope you enjoy the photos. Looking forward to seeing everyone there!” Chuck Slusarczyk is an avid member of the Ohio birding community, and his efforts to assist and educate novice birders via social media are well known, yet he is the first to admit that one never stops learning. He has presented a number of programs to Black River Audubon, always drawing a large, appreciative gathering. 2019 Wellington Area Christmas Bird Count The Wellington-area CBC will take place Saturday, December 28, 2019. Meet at the McDonald’s on Rt. 58 at 8:00 a.m. The leader is Paul Sherwood. -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis Mcintosh

COM . TOCK S HUTTER © S © BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis McIntosh For passionate birdwatcher Sandy Komito of over age 16 say they actively observe and try to iden- Fair Lawn, New Jersey, 1998 was a big year. In a tify birds, although few go to the extremes Komito tight competition with two fellow birders to see as did. About 88 percent are content to enjoy bird many species as possible in a single year, Komito watching in their own backyards or neighborhoods. traveled 270,000 miles, crisscrossing North Amer- More avid participants plan vacations around ica and voyaging far out to sea to locate rare and their hobby and sometimes travel long distances to elusive birds. In the end, he set a North American view a rare species and add it to their lifelong list of record of 748 species, topping his own previous birds spotted. Many birdwatchers, both casual and record of 726, which had stood for 11 years. serious, also function as citizen scientists, provid- Komito and his fellow competitors are not alone ing valuable data to help scientists monitor bird in their love of birds. According to a U.S. Fish and populations and create management guidelines to Wildlife Service survey, about one in five Americans protect species in decline. 36 2 0 1 4 N UMBER 1 | E NGLISH T E ACHING F ORUM Birding Basics The origins of bird watching in the United States date back to the late 1800s when conserva- tionists became concerned about the hunting of birds to supply feathers for the fashion industry. -

2016 LBRC Newsletter

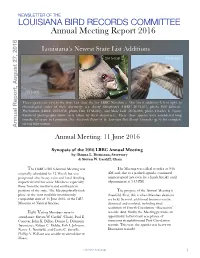

NEWSLETTER OF THE LOUISIANA BIRD RECORDS COMMITTEE Annual Meeting Report 2016 Louisiana’s Newest State List Additions 2015-058 2016-003 August 27, 2016 2014-031 Three species are new to the State List since the last LBRC Newsletter. Our latest additions (left to right, in chronological order of their discovery) are: Sooty Shearwater (LBRC 2014-031, photo Will Selman), Pyrrhuloxia (LBRC 2015-058, photo Dan O’Malley), and Mew Gull (2016-003, photo Charles E. Lyon). Excellent photographs above were taken by their discoverers. These three species were considered long overdue to occur in Louisiana. See Nineteenth Report of the Louisiana Bird Records Committee (p. 6) for complete record information. Annual Report, Annual Meeting: 11 June 2016 Synopsis of the 2016 LBRC Annual Meeting by: Donna L. Dittmann, Secretary & Steven W. Cardiff, Chair The LBRC’s 2016 Annual Meeting was The Meeting was called to order at 9:56 originally scheduled for 12 March but was AM and, due to a packed agenda, continued postponed after heavy rains and local flooding uninterrupted (not even for a lunch break!) until impacted travel for some Members, especially adjournment at 5:45 PM. those from the northern and southeastern portions of the state. The Meeting finally took The purpose of the Annual Meeting is place on the next available unanimously threefold. First, this is when Member elections compatible date of 11 June 2016, at the LSU are held. Second, additional business can be Museum of Natural Science. discussed and resolved, including final resolution of Fourth Circulation “Discussion” Eight Voting Members were in records. -

THE OBSERVER Volume 72, Issue 5 January 2017

THE OBSERVER Volume 72, Issue 5 January 2017 Visit our website www.whittieraudubon.org Editor’s note Big Year News Editor’s note: KEEP THE DATE! Our annual Conservation Dinner will be March 16, 2017. Join us as we honor Annual Conservation Bob Henderson and his many years of dedication to Whittier and its Award environmental causes. Check our website for ticket info. Kids Space: Audubon Proceeds are used to place Audubon Adventures into classrooms. See our Kids Adventures Partnership Space section for exciting news. Jennifer Schmahl General meeting info BIRDERS MAKE “BIG YEAR” HISTORY. Four break 2013 mark Field trip schedule of 749. From ABA Blog by Nate Swick We are a chapter of National Audubon Past trip write-up (blog.aba.org) KIDS SPACE Congratulations to John Wiegel (780) Olaf General Meeting for Danielson (776) Laura Keene (759) and We are very happy to Christian Hagenlocher (750) who all broke announce we are providing December the seemingly unbreakable one year bird Audubon Adventures to five A fascinating illustrated count of 749 species. Traveling all over the afterschool programs in the program on insects, "Six Legs North American continent to spy and Norwalk/La Mirada Unified Good", will be given by Robb document hundreds of bird species in one School District. Hamilton at the January 19, calendar year, a birder must have time, 2017 meeting of the Whittier money, dedication and a vast knowledge of We have been emphasizing bird species to succeed in this personal our commitment to educational Audubon Society at 7:30 p.m. challenge. The official ABA checklist outreach for the past several includes 993 species. -

Hummerbird Celebration: the Big Year

For Immediate Release Contact: Sandy Jumper Vice President of Marketing and Promotion Rockport-Fulton Chamber of Commerce [email protected] (361) 729.6445 HummerBird Celebration: The Big Year An event celebrating the spectacular fall migration of hummingbirds Rockport-Fulton, Texas Celebrate the Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and all fall migrants at the 31st Annual HummerBird Celebration in Rockport and Fulton, Texas, Thursday - Sunday September 19-22. At 5 p.m. Thursday, Sept. 19, attendees will be treated to a Welcome Reception at the Rockport Center for the Arts building located at 101 S. Austin St. in Downtown Rockport. It is free to all attendees. It features wine, cheese, fine art and information on the event. The opening dinner will be a Texas Style Barbecue at the newly remodeled Saltwater Pavilion of Rockport Beach from 6:30 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. This is a ticketed event. Over the three-day event period, event attendees have an array of activities to experience. The choices include: guided bus trips to see the hummingbirds, boat and nature tours, photography talks, field trips guided by experts, lectures from world renowned speakers, workshops, outdoor exhibits and two Hummer Malls filled with vendors marketing nature-related products. Each day is filled with something special such as the Opening Texas Barbecue Dinner on Thursday, Sept. 19, featuring local birder of the year Martha McLeod and Niharika Raiput, a wildlife and conservation artist from New Delhi, India. Friday's highlight is the live bird talk given by representatives from Sky King Falconry out of San Antonio. Saturday begins with a unique Hummer Breakfast on the grounds of the History Center of Aransas County, and ends with the keynote presentation from Greg Miller, a world renowned birder whose character was played by Hollywood actor, Jack Black in the movie "The Big Year". -

My Big Bird Year Fly Free, Subaraj the International and Domestic

Official Magazine of Nature Society (Singapore) Volume 28 No 1 Jan-Mar 2020 S$5.00 My Big Bird Year Fly Free, Subaraj The International and Domestic Parrot Trade MCI (P) 064/04/2019 MESSAGE FROM THE EDITORS NATURE SOCIETY (SINGAPORE) his issue has serendipitously turned into a year-end celebration of the many generations that make up the nature loving community and TNature Society (Singapore) (NSS) members in our tiny island country, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016 and the continuity of commitment. Our cover photo shows a young team competing in NSS’ 35th Singapore Patron Professor Tommy Koh Bird Race. This event attracted the largest number of teams and participants President ever, thanks not only to the many keen young primary and secondary Dr Shawn Lum school participants, but also the slightly older groups of photographers and Vice-President Dr Ho Hua Chew birdwatchers who took part. And the few even older ones. And the youngsters Immediate Past President needed a solid core of “middling-age” types, teachers and NSS volunteers, to Dr Geh Min keep them safe as they roamed around the southern ridges. Honorary Secretary Mr Morten Strange At the core of the Bird Race organisation was Lim Kim Chuah, now Honorary Treasurer Chair of the NSS Bird Group, and one of those who had competed in the first Mr Bhagyesh Chaubey Bird Race in 1984 – a two team event. He was one of the young generation of Honorary Assistant Secretary Ms Evelyn Ng Singaporeans who gave the Society, then the Singapore Branch of the Malayan Honorary Assistant Treasurer Nature Society, a power surge in the 1980s. -

PPCO Twist System

PHOTO SALON The Next Big Thing Laura Keene's Photographic Big Year ig-list birding is one of the ABA’s oldest and most storied traditions. There are shelves of books, not to mention a major motion picture, chronicling the stories of ABA Area Big Years, as well as inter- national efforts. Roger Tory Peterson and James Fisher’s 1954 Big Year continues to thrill us, and, as Kenn BKaufman has noted, Lynds Jones and pals were doing Big Days as long ago as the late 19th century. At first blush, the Big Year seems easy. What’s the Big Deal? You spend a year traveling all over the place looking at birds. But once you get to reading about Big Years, or attempting your own, certain themes begin to emerge: surprisingly complex strategies, frustration and loneliness, real hardship and sometimes outright danger, strained relationships… The central challenge of a Big Year is seeing or hearing all the species well enough to be able to say for certain that they belong on your checklist. Talk to any of the guides who have worked with Big Year birders over the years—from Attu to Florida and now Hawaii—and eventually you’ll get a little smile and an eye roll when discussing whether this or that birder actually saw this or that bird. It comes with the ter- ritory. Our lists are our own, and whether we’ve had a “good enough look” is up to each birder. Which is where Laura Keene’s unprecedented 2016 effort comes in. During her 2016 ABA Area Big Year, Laura saw 815 species—and physically documented 802 of them. -

A New Nest Record After Dropping Substantially in the Early 2000S, NRS Annual Totals Are Now at Their Highest Level Since the Scheme Began in 1939

The newsletter of the Nest Record Scheme Issue 29 may 2013 InsIde thIs edItIon 03 in The NewS 04 NRS laTeST ReSulTS 05 DaVID Glue’S RepoRT oN 2012 06 getting moRe fRom box moNIToRING 08 NRS aNNual ToTalS 10 2012 Top NeSTeRS 11 neST RecoRDING oN a ReSeRVe 13 uRbaN wooDpIGeoN moNIToRING 14 neSTING ‘bIG yeaR’ 16 SpoT The NeST plus TRIbuTe To alaN buRGess, New paRTIcIpaNTS IN 2012, awaRD foR bob SheppaRD Thanks to Mark Joy for this great photo of a Goldfinch attending a brood of chicks. See page 4 for our appeal for more finch records. a new nest record after dropping substantially in the early 2000s, NRS annual totals are now at their highest level since the scheme began in 1939. n the early 2000s, participation in We’re extremely grateful to all nest the Nest Record Scheme was waning. recorders for their help getting NRS e R Annual submission totals were down back on track: new recorders, recorders mo I a quarter on 1990s levels and far fewer who have helped with recruitment and DINS N a I records were being submitted for those training, recorders who have focused ll GI species whose nests are more challenging on priority species, and recorders who e, to find. have made sure that well-monitored RIDG b NRS News 28 RIS Last spring, in , we species continue to be well-monitored. , ch S reported how far the Scheme had We’re also grateful for funding from the e RID since come, with numbers of active Dilys Breese project, which has made e b e N recorders up 35% and lots more development work on NRS possible. -

Western Field Ornithologists September 2020 Newsletter

Western Field Ornithologists September 2020 Newsletter Black Skimmers, Marbled Godwits, and Forster’s Terns. Imperial Beach, San Diego County. 3 September 2009. Photo by Thomas A. Blackman. Christopher Swarth, Newsletter Editor http://westernfieldornithologists.org/ What’s Inside…. Farewell from President Kurt Leuschner Welcome to New Board Members Alan Craig Remembers the Early Days of WFO Jon and Kimball on Bird Taxonomy and the NACC Western Regional Bird Highlights by Paul Lehman Steve Howell: A Big Year by Foot in Town Over-eager Nuthatches and Willing Sapsuckers Meet the WFO Board Members Awards and new WFO Leadership Kimball’s Life and Covid-time in a New Home Book reviews Student Research Field Notes and Art Announcements and News Kurt Leuschner’s President’s Farewell These past two years have been an interesting time to be the President of Western Field Ornithologists. We had one of our most successful conferences in Albuquerque, and just before the lockdown we completed a very memorable WFO field trip to Tasmania. We accomplished a lot together, and I look forward to assisting with future planning when the world opens up again – and it will! While we may not know exactly what lies ahead, we certainly won’t take anything for granted. We’re in the midst of a worldwide discourse about the serious impacts of social injustice. How the ornithological community can help improve the experiences of minorities in field ornithology continues to be on our minds as we move forward into 2021. Our new WFO Diversity and Inclusivity subcommittee has met two times already, and we will continue to discover and to implement ways to bring more under- represented groups into the world of birds. -

The Big Year: a Tale of Man, Nature, and Fowl Obsession Kindle Edition the Big Year (The Movie)

The Big Year, the book and movie about the 365 day marathon of birdwatching, to find and identify an extraordinary 745 different species of birds by official year-end count. http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B0036QVOHS/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?ie=UTF8&btkr=1 The Big Year: A Tale of Man, Nature, and Fowl Obsession Kindle Edition Every year on January 1, a quirky crowd of adventurers storms out across North America for a spectacularly competitive event called a Big Year -- a grand, grueling, expensive, and occasionally vicious, "extreme" 365-day marathon of birdwatching. For three men in particular, 1998 would be a whirlwind, a winner-takes-nothing battle for a new North American birding record. In frenetic pilgrimages for once-in-a-lifetime rarities that can make or break their lead, the birders race each other from Del Rio, Texas, in search of the rufous-capped warbler, to Gibsons, British Columbia, on a quest for Xantus's hummingbird, to Cape May, New Jersey, seeking the offshore great skua. Bouncing from coast to coast on their potholed road to glory, they brave broiling deserts, roiling oceans, bug-infested swamps, a charge by a disgruntled mountain lion, and some of the lumpiest motel mattresses known to man. The unprecedented year of beat-the-clock adventures ultimately leads one man to a new record -- one so gigantic that it is unlikely ever to be bested...finding and identifying an extraordinary 745 different species by official year-end count. Prize-winning journalist Mark Obmascik creates a rollicking, dazzling narrative of the 275,000-mile odyssey of these three obsessives as they fight to the finish to claim the title in the greatest -- or maybe the worst -- birding contest of all time.