Film Literacy & Education in Singapore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14

Radio 4 Listings for 2 – 8 May 2020 Page 1 of 14 SATURDAY 02 MAY 2020 Professor Martin Ashley, Consultant in Restorative Dentistry at panel of culinary experts from their kitchens at home - Tim the University Dental Hospital of Manchester, is on hand to Anderson, Andi Oliver, Jeremy Pang and Dr Zoe Laughlin SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000hq2x) separate the science fact from the science fiction. answer questions sent in via email and social media. The latest news and weather forecast from BBC Radio 4. Presenter: Greg Foot This week, the panellists discuss the perfect fry-up, including Producer: Beth Eastwood whether or not the tomato has a place on the plate, and SAT 00:30 Intrigue (m0009t2b) recommend uses for tinned tuna (that aren't a pasta bake). Tunnel 29 SAT 06:00 News and Papers (m000htmx) Producer: Hannah Newton 10: The Shoes The latest news headlines. Including the weather and a look at Assistant Producer: Rosie Merotra the papers. “I started dancing with Eveline.” A final twist in the final A Somethin' Else production for BBC Radio 4 chapter. SAT 06:07 Open Country (m000hpdg) Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Helena Merriman Closed Country: A Spring Audio-Diary with Brett Westwood SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (m000j0kg) tells the extraordinary true story of a man who dug a tunnel into Radio 4's assessment of developments at Westminster the East, right under the feet of border guards, to help friends, It seems hard to believe, when so many of us are coping with family and strangers escape. -

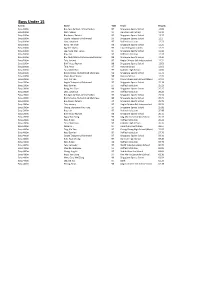

Boys Under 15

Boys Under 15 Events Name YOB Team Results Boys 100m Bin Agos Sahbali, Amirul Sofian 97 Singapore Sports School 12.09 Boys 100m Moh, Shaun 97 Dunman High School 12.11 Boys 100m Bin Anuar, Zuhairi 97 Singapore Sports School 12.17 Boys 100m Sugita Tadayoshi, Richmond 97 Singapore Sports School 12.2 Boys 100m Lew, Jonathon 97 Raffles Institution 12.23 Boys 100m Kang, Yee Cher 98 Singapore Sports School 12.25 Boys 100m Ng, Kee Hsien 97 Hwa Chong Institution 12.25 Boys 100m Lee, Song Wei, Lucas 97 Singapore Sports School 12.36 Boys 100m Poy, Ian 97 Raffles Institution 12.37 Boys 100m Bin Abdul Wahid, Muhammad Syazani 98 Singapore Sports School 12.44 Boys 100m Toh, Jeremy 97 Anglo Chinese Sch Independant 12.51 Boys 100m Bin Fairuz, Rayhan 98 Singapore Sports School 12.63 Boys 100m Thia, Aven 97 Victoria School 12.63 Boys 100m Tan, Chin Kean 97 Catholic High School 12.66 Boys 100m Bin Norzaha, Muhammad Shahrieza 98 Singapore Sports School 12.72 Boys 100m Chen, Ryan Shane 98 Victoria School 12.73 Boys 200m Ong, Xin Yao 97 Chung Cheng High School (Main) 24.91 Boys 200m Sugita Tadayoshi, Richmond 97 Singapore Sports School 25.18 Boys 200m Kee, Damien 97 Raffles Institution 25.23 Boys 200m Kang, Yee Cher 98 Singapore Sports School 25.25 Boys 200m Lew, Jonathon 97 Raffles Institution 25.26 Boys 200m Bin Agos Sahbali, Amirul Sofian 97 Singapore Sports School 25.50 Boys 200m Bin Norzaha, Muhammad Shahrieza 98 Singapore Sports School 25.71 Boys 200m Bin Anuar, Zuhairi 97 Singapore Sports School 25.72 Boys 200m Toh, Jeremy 97 Anglo Chinese Sch Independant -

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland a study © Adrienne Clare Scullion Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD to the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow. March 1992 ProQuest Number: 13818929 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818929 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Frontispiece The Clachan, Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, 1911. (T R Annan and Sons Ltd., Glasgow) GLASGOW UNIVERSITY library Abstract This study investigates the cultural scene in Scotland in the period from the 1880s to 1939. The project focuses on the effects in Scotland of the development of the new media of film and wireless. It addresses question as to what changes, over the first decades of the twentieth century, these two revolutionary forms of public technology effect on the established entertainment system in Scotland and on the Scottish experience of culture. The study presents a broad view of the cultural scene in Scotland over the period: discusses contemporary politics; considers established and new theatrical activity; examines the development of a film culture; and investigates the expansion of broadcast wireless and its influence on indigenous theatre. -

A Teaching Guide to Using Film and Television with Three- to Eleven-Year Olds Education

LOOKLOOK AGAIN!AGAIN! A teaching guide to using film and television with three- to eleven-year olds Education This publication has been made possible by the generosity of the Department for Education and Skills (DfES). LOOK AGAIN! A teaching guide to using film and television with three- to eleven-year-olds Education ma vie en rose | courtesy of bfi stills LOOK AGAIN ii CREDITS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This publication has been made possible by the British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data British Film Institute Primary Education Working bfi staff involved generosity of the Department for Education and A catalogue record for this book is available from Group 2002-2003 Cary Bazalgette, Head of Education Development Skills (DfES). the British Library. Wendy Earle, Resources Editor Ann Aston, Deputy Head Teacher, Robin Hood Hilary Pearce, 5–14 Development Officer Written and produced by the Primary Education ISBN: 1–903786–11–8 Primary School, Birmingham Dr David Parker, Research Officer Working Group convened by bfi Education. The copyright for this teaching guide belongs to Helen Bromley, independent Early Years the British Film Institute. consultant The Working Group would like to thank the Designed by: Alex Cameron and Kelly Al-Saleh Margaret Foley, Quality Improvement Officer numerous teachers, advisers and literacy If you would like to reproduce anything in this 0–14, Dundee City Council consultants in all parts of the UK who contributed Film stills: guide for any other purpose, please contact the Mary Hilton, Lecturer in Primary English, Faculty to the development process and the experiences courtesy of bfi Stills, Ann Aston, Christopher Resources Editor, bfi Education, 21 Stephen of Education, University of Cambridge cited in this Guide, and in particular Geoff Dean, Duriez, Juliet McCoen, Alison Hempstock, Street, London W1T 1LN. -

Dunman High School 德明政府中学 Dunman High School • 德明政府中学 02 Joint Admissions Exercise

DUNMAN HIGH SCHOOL 德明政府中学 DUNMAN HIGH SCHOOL • 德明政府中学 02 JOINT ADMISSIONS EXERCISE SCHOOL PHILOSOPHY VISION The premier school of Leaders of Honour MISSION To nurture our students to Care, to Serve, and to Lead MOTTO Honesty, Trustworthiness, Moral Courage, Loyalty DUNMAN HIGH SCHOOL • 德明政府中学 JOINT ADMISSIONS EXERCISE 03 DUNMANIAN OUTCOMES MORAL INTEGRITY Students are guided by honesty, trustworthiness, moral courage and loyalty. PASSION FOR LIFE & LEARNING Students are always learning and striving to be their best. IDEALISM Students have the conviction to make a difference to the world. 21ST CENTURY COMPETENCIES Students are proficient in critical and creative thinking, communication and information skills. BILINGUALISM & MULTICULTURALISM Students are effectively bilingual in English and Chinese, appreciate different cultures and navigate them with ease. ACTIVE CITIZENRY Students are global citizens rooted in Singapore who serve the community, both local and beyond. DUNMAN HIGH SCHOOL • 德明政府中学 04 JOINT ADMISSIONS EXERCISE CONTENTS 05 Principal’s Foreword 14 Senior High Co-Curriculum 06 What is the Dunmanian Edge? 16 Academic Achievements 07 Dunman High School in the 17 Careers, Scholarships and Words of Dunmanians: Higher Education Past, Present and Future 18 Your Future Beyond 08 Dunmanians Around the World Dunman High 10 Senior High Curriculum DUNMAN HIGH SCHOOL • 德明政府中学 JOINT ADMISSIONS EXERCISE 05 PRINCIPAL’S FOREWORD “The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. Intelligence plus character — that is the goal of true education.” – Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Dr. King’s vision about the goal of education is and a CCA Leader, embodying our school’s most relevant in today’s world where solutions mission – “To Care, To Serve, and To Lead”. -

Download (PDF)

2021 Industry Guide 44th Göteborg Film Festival goteborgfilmfestival.se Jan 29–Feb 8 2021 #gbgfilmfestival Contents 5 Welcome 16 Industry Programmes 6 Online universe 18 Nordic Competition of Industry 2021 Short guide to our 20 International Competition digital platform. 22 Nordic Documentary 8 Accreditation Guide Competition An explicit visual guide of what's 34 Nostradamus Academy included in your accreditation. Exclusive training programme for film and television 9 Digital self-care industry professionals. 37 Film Production in 11 Discover the West Sweden 44th Göteborg 38 Who's who at Göteborg Film Festival Film Festival? Read more about the 24 Ingmar Bergman festival's annual focus, Competition special programmes, guests and competitions. 26 Nordisk Film & TV Fond Prize 28 Swedish Shorts Competition 30 Nordic Film Lab Nordic Film Lab is an exclusive networking forum for upcoming Scandinavian filmmakers. Cover photo from Gagarine. Industry Guide 2021 – Göteborg Film Festival Göteborg Film Festival Editor: Josef Kullengård, Liisa Nurmela Olof Palmes Plats 1 Editorials: Cia Edström, Nicholas Davies 413 04 Göteborg, Sweden Layout: Felicia Fortes Tel: +46 31 339 30 00 Photo Editor: Linda Petersson E-mail: [email protected] www.goteborgfilmfestival.se 3 4 From Undine Welcome to the 44th Göteborg Film Festival Welcome to the Göteborg Film Festival. For 44 The festival’s industry programme – the years, Scandinavia’s leading film festival pro- Nordic Film Market, TV Drama Vision, Nostrada- gramme has been presented in cinemas packed mus and Film Forum Sweden – transforms into a with expectant audiences and filmmakers. Over multidimensional digital space to offer industry time, the festival audience has become one of delegates exclusive live online sessions, network- the largest in Europe; in a normal year, audiences ing and engaging high-end content. -

A*Star Talent Search and Singapore Science & Engineering Fair 2020 Contents

A*STAR TALENT SEARCH AND SINGAPORE SCIENCE & ENGINEERING FAIR 2020 CONTENTS 03 Singapore Science & Engineering Fair (SSEF) 05 Foreword by Mdm Lee Lin Yee Chairperson, Singapore Science & Engineering Fair 2020 Working Committee 07 Singapore Science & Engineering Fair (SSEF) 2020 Winners 33 A*STAR Talent Search (ATS) 35 Foreword by Prof Ho Teck Hua Chairperson, A*STAR Talent Search 2020 Awards Committee 37 A*STAR Talent Search (ATS) 2020 Finalists 45 Acknowledgements 47 A*STAR Talent Search and Singapore Science & Engineering Fair 2020 Participants SINGAPORE SCIENCE & ENGINEERING FAIR BACKGROUND SSEF 2020 The Singapore Science & Engineering Fair (SSEF) is a national 592 projects were registered online for the SSEF this year. Of these, competition organised by the Ministry of Education (MOE), 320 were shortlisted for judging in March 2020. The total number of the Agency for Science, Technology & Research (A*STAR) and awards for the Main Category was 117, comprising 27 Gold, 22 Silver, Science Centre Singapore. The SSEF is affiliated to the highly 33 Bronze and 35 Merit awards. Additionally, 47 projects were also prestigious Regeneron International Science and Engineering awarded Special Awards sponsored by six different organisations Fair (Regeneron ISEF), which is regarded as the Olympics of (Institution of Chemical Engineers Singapore, Singapore University science competitions. of Technology and Design, Singapore Society for Microbiology and Biotechnology, Yale-NUS College, The Electrochemical Society, and SSEF is open to all secondary and pre-university students Singapore Association for the Advancement of Science). between 15 and 20 years of age. Participants submit research projects on science and engineering. In the Junior Scientists Category (for students under 15 years of age), 49 projects were shortlisted at the SSEF this year. -

Rediscover Northern Ireland Report Philip Hammond Creative Director

REDISCOVER NORTHERN IRELAND REPORT PHILIP HAMMOND CREATIVE DIRECTOR CHAPTER I Introduction and Quotations 3 – 9 CHAPTER II Backgrounds and Contexts 10 – 36 The appointment of the Creative Director Programme and timetable of Rediscover Northern Ireland Rationale for the content and timescale The budget The role of the Creative Director in Washington DC The Washington Experience from the Creative Director’s viewpoint. The challenges in Washington The Northern Ireland Bureau Publicity in Washington for Rediscover Northern Ireland Rediscover Northern Ireland Website Audiences at Rediscover Northern Ireland Events Conclusion – Strengths/Weaknesses/Potential Legacies CHAPTER III Artist Statistics 37 – 41 CHAPTER IV Event Statistics 42 – 45 CHAPTER V Chronological Collection of Reports 2005 – 07 46 – 140 November 05 December 05 February 06 March 07 July 06 September 06 January 07 CHAPTER VI Podcasts 141 – 166 16th March 2007 31st March 2007 14th April 2007 1st May 2007 7th May 2007 26th May 2007 7th June 2007 16th June 2007 28th June 2007 1 CHAPTER VII RNI Event Analyses 167 - 425 Community Mural Anacostia 170 Community Poetry and Photography Anacostia 177 Arts Critics Exchange Programme 194 Brian Irvine Ensemble 221 Brian Irvine Residency in SAIL 233 Cahoots NI Residency at Edge Fest 243 Healthcare Project 252 Camerata Ireland 258 Comic Book Artist Residency in SAIL 264 Comtemporary Popular Music Series 269 Craft Exhibition 273 Drama Residency at Catholic University 278 Drama Production: Scenes from the Big Picture 282 Film at American Film -

This Document Was Written in 1995 and Concerns Memories O

******************************************************** Disclaimer: This document was written in 1995 and concerns memories of 1930s life; as such there may be opinions expressed or words used that do not meet today’s norms and expectations. * Transcript ID: MH-95-111PL001 * Scan ID: MH-95-111PL001 * CCINTB Document ID: 95-111-1a-b * Number of pages: 4 * Date sent: 20 February 1995 * Transcribed by: TP Transcription Limited/Standardised by: Jamie Terrill * Format: Letter * Details: from Margaret Houlgate to Annette Kuhn and Valentina Bold * Notes: This transcription has rendered the original text as written, including some spelling and grammatical errors. Letter in response to 1995 campaign for the collection of cinemagoing memories. ******************************************************** [redacted], [redacted], Lyndhurst, Hants, [redacted] [redacted] Annette Kuhn and Valentina Bold Department of Theatre Film and Television Studies, University of Glasgow Florentine House, 53 Hillhead Street, Glasgow, G12 8QF. 20.2.95 Dear Both, I was interested to read your filmgoers' project and wonder whether any of my memories are of interest. I was growing up in Croydon in the 1920’s and 1930’s when "going to the pictures" was the main entertainment and interest of people of all ages. There were at least 10 cinemas within bus or cycling distance from my home, all with double features plus Pathe news, "Wonders of Nature", cartoons, and trailers for the following week, or part of the week if programmes were changed midweek. We had a wonderful choice. As well as the film programme, some of the larger cinemas had a floor show, or cinema organ which arose from the depths, and which played for 20 minutes as lights round the stage changed colour. -

SECONDARY SCHOOL EDUCATION Shaping the Next Phase of Your Child’S Learning Journey 01 SINGAPORE’S EDUCATION SYSTEM : an OVERVIEW

SECONDARY SCHOOL EDUCATION Shaping the Next Phase of Your Child’s Learning Journey 01 SINGAPORE’S EDUCATION SYSTEM : AN OVERVIEW 03 LEARNING TAILORED TO DIFFERENT ABILITIES 04 EXPANDING YOUR CHILD’S DEVELOPMENT 06 MAXIMISING YOUR CHILD’S POTENTIAL 10 CATERING TO INTERESTS AND ALL-ROUNDEDNESS 21 EDUSAVE SCHOLARSHIPS & AWARDS AND FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE SCHEMES 23 CHOOSING A SECONDARY SCHOOL 24 SECONDARY 1 POSTING 27 CHOOSING A SCHOOL : PRINCIPALS’ PERSPECTIVES The Ministry of Education formulates and implements policies on education structure, curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. We oversee the development and management of Government-funded schools, the Institute of Technical Education, polytechnics and autonomous universities. We also fund academic research. SECONDARY SCHOOL 01 EDUCATION 02 Our education system offers many choices Singapore’s Education System : An Overview for the next phase of learning for your child. Its diverse education pathways aim to develop each child to his full potential. PRIMARY SECONDARY POST-SECONDARY WORK 6 years 4-5 years 1-6 years ALTERNATIVE SPECIAL EDUCATION SCHOOLS QUALIFICATIONS*** Different Pathways to Work and Life INTEGRATED PROGRAMME 4-6 Years ALTERNATIVE UNIVERSITIES QUALIFICATIONS*** SPECIALISED INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS** 4-6 Years WORK PRIVATELY FUNDED SCHOOLS SPECIAL 4-6 Years EDUCATION PRIMARY SCHOOL LEAVING EXPRESS GCE O-LEVEL JUNIOR COLLEGES/ GCE A-LEVEL CONTINUING EDUCATION EXAMINATION (PSLE) 4 Years CENTRALISED AND TRAINING (CET)**** INSTITUTE 2-3 Years Specialised Schools offer customised programmes -

DETAIL 1 24Th February 2018 Saturday Air Rifle Wome

24th – 27th February 2018 SAFRA Yishun Indoor Air Weapons Range DAY 1 – DETAIL 1 Air Rifle Women (Open/School) 24th February 2018 Preparation and Sighting Time: 0900 hrs Saturday Start Time: 0915 hrs FP Name Organisation Event Entry 01 02 TAN HONG YING Raffles Institution (Year 5-6) ARW(S) 1st Team 03 LIM SI TING Hwa Chong Institution (College) ARW(S) 1st Team 04 FERNEL TAN QIAN NI Singapore Sports School ARW(S) 1st Team 05 CLAIRE NG WEI TENG Yishun Town Secondary School ARW(S) 1st Team 06 CHEW LIU IM Raffles Institution (Year 5-6) ARW(S) 1st Team 07 LEE JING LE Singapore Sports School ARW(S) 2nd Team 08 LIM IVY HomeTeamNS Air Gun Interest Group ARW(O) Individual 09 NICOLE CHAN SHI QI Hwa Chong Institution (College) ARW(S) 1st Team 10 11 TAN MEI YI RENEE SAFRA Shooting Club ARW(O) 1st Team 12 YEO SHI NING KYM Yishun Town Secondary School ARW(S) 1st Team 13 ZHENG XIAYU Hwa Chong Institution (College) ARW(S) 1st Team 14 NUS National University of Singapore ARW(O) 1st Team 15 LEE KELLI-ANN Raffles Institution (Year 5-6) ARW(S) 2nd Team 16 JOY PNG SAFRA Shooting Club ARW(O) 1st Team 17 18 LONG HUI YING NATALIE Yishun Town Secondary School ARW(S) 3rd Team 19 CECILIA NG Singapore Sports School ARW(S) 1st Team 20 ONG TZE YEE CLAIRE Hwa Chong Institution (College) ARW(S) Individual 21 TAY SEE YEN SOPHIE Raffles Institution (Year 5-6) ARW(S) 1st Team 22 CALLIE SIAH YONG XIN Singapore Sports School ARW(S) 2nd Team 23 RAUDHAH NAFISAH BTE HAKIM Yishun Town Secondary School ARW(S) Individual 24 NURUL SYAFIQA BINTE NASSARUDDIN Singapore Sports School -

Interview with Alexander Horwath: on Programming and Comparative Cinema

FILMS UNDER DISCUSSION / INTERVIEW · Cinema Comparat/ive Cinema · Vol. I · No. 1. · 2012 · 12-31 Interview with Alexander Horwath: On Programming and Comparative Cinema Álvaro Arroba (in collaboration with Olaf Möller) ABSTRACT In this interview (realised in collaboration with Olaf Möller), Alexander Horwath takes Jean-Luc Godard’s text ‘Les Cinémathèques et l’histoire du cinéma’ (1979) and his film Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988–98) as a point of departure to discuss: programming as a form of comparative cinema; the Cinémathèques as a place of production; different forms of criticism and writing on film; spatial vs. temporal (or consecutive) comparison; video as a tool to create a form different to cinema itself; programming as a form of historiography in the context of a Cinémathèque; and different programming methods (examples discussed include Peter Kubelka’s programme ‘Was ist Film’ [‘What is Film?’] or Horwath’s own programme for documenta 12 in Kassel in 2007). Finally, Horwath discusses the 1984 Congress of the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF), celebrated in Vienna and dedicated to ‘non-industrial’ films; the existence of an ‘ethical-realist’ critical tradition in France vis-à-vis the ‘experimental’ tradition; the role of the most important film-makers of the Austrian avant-garde in relation to the Austrian Film Museum in 1968; the work of film curator Nicole Brenez; and the so-called ‘expanded cinema’, which he distinguishes from current museum practices or the new digital formats that prevail today. KEYWORDS Jean-Luc Godard, Histoire(s) du cinéma, programming, Austrian Film Museum, Peter Kubelka, ‘Was Ist Film’, documenta 12, comparative cinema, Austrian avant-garde, expanded cinema, Nicole Brenez.