Chronic Lyme Disease and Co-Infections: Differential Diagnosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abscess Prevention

ABSCESS PREVENTION ▪ Chest pains may occur if infection How do you soak/use Avoiding abscesses goes to heart or lungs compresses? • Wash your hands and the injection site. What should I do if I get ▪ Use warm/hot water (that doesn’t burn your skin) • Use alcohol pads and wipe an abscess? ▪ Soak in tub of plain hot water or hot back & forth (rub hard) over ▪ Treat at home with warm soaks water with Epsom salts injection site to remove dirt. only if: ▪ Use hot, wet, clean washcloth and - No red streaks hold on abscess, if abscess cannot • Then use another new alcohol - Skin not hot and puffy be soaked in tub pad for the final cleaning. ▪ Soak abscess 3 to 4 times a day for ▪ Go to a clinic if abscess: 10-15 minutes each time, if possible What is a skin abscess? - Not improving, especially ▪ Cover with a clean dry bandage after after 5-7 days soaking ▪ Pocket of pus - Gets bigger and/or very ▪ soaking/using compresses ▪ Often found at injection sites, but STOP painful when abscess starts draining can be found elsewhere - Is hot and puffy ▪ More likely with Red streaks start spreading skin-popping from the abscess-go ASAP! muscling What about missing a vein ▪ Go to emergency room if: ▪ May occur even after you stop Chest pain antibiotics? injecting High fever, chills ▪ Take all antibiotics, if Infection looks like it is How do you know it’s an spreading fast prescribed, even if you feel better abscess? ▪ Take antibiotics after you fix (if ▪ using heroin) ▪ Pink or reddish lump on skin ▪ Do not take antibiotics with ▪ Tender or painful Warning -

LYME DISEASE Other Names: Borrelia Burgdorferi

LYME DISEASE Other names: Borrelia burgdorferi CAUSE Lyme disease is caused by a spirochete bacteria (Borrelia burgdorferi) that is transmitted through the bite from an infected arthropod vector, the black-legged or deer tick Ixodes( scapularis). SIGNIFICANCE Lyme disease can infect people and some species of domestic animals (cats, dogs, horses, and cattle) causing mild to severe illness. Although wildlife can be infected by the bacteria, it typically does not cause illness in them. TRANSMISSION The bacteria has been observed in the blood of a number of wildlife species including several bird species but rarely appears to cause illness in these species. White-footed mice, eastern chipmunks, and shrews serve as the primary natural reservoirs for Lyme disease in eastern and central parts of North America. Other species appear to have low competencies as reservoirs for the bacteria. The transmission of Lyme disease is relatively convoluted due to the complex life cycle of the black-legged tick. This tick has multiple developmental stages and requires three hosts during its life cycle. The life cycle begins with the eggs of the ticks that are laid in the spring and from which larval ticks emerge. Larval ticks do not initially carryBorrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria must be acquired from their hosts they feed upon that are carriers of the bacteria. Through the summer the larval ticks feed on the blood of their first host, typically small mammals and birds. It is at this point where ticks may first acquireBorrelia burgdorferi. In the fall the larval ticks develop into nymphs and hibernate through the winter. -

Phagocytosis of Borrelia Burgdorferi, the Lyme Disease Spirochete, Potentiates Innate Immune Activation and Induces Apoptosis in Human Monocytes Adriana R

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn UCHC Articles - Research University of Connecticut Health Center Research 1-2008 Phagocytosis of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme Disease Spirochete, Potentiates Innate Immune Activation and Induces Apoptosis in Human Monocytes Adriana R. Cruz University of Connecticut School of Medicine and Dentistry Meagan W. Moore University of Connecticut School of Medicine and Dentistry Carson J. La Vake University of Connecticut School of Medicine and Dentistry Christian H. Eggers University of Connecticut School of Medicine and Dentistry Juan C. Salazar University of Connecticut School of Medicine and Dentistry See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/uchcres_articles Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cruz, Adriana R.; Moore, Meagan W.; La Vake, Carson J.; Eggers, Christian H.; Salazar, Juan C.; and Radolf, Justin D., "Phagocytosis of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme Disease Spirochete, Potentiates Innate Immune Activation and Induces Apoptosis in Human Monocytes" (2008). UCHC Articles - Research. 182. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/uchcres_articles/182 Authors Adriana R. Cruz, Meagan W. Moore, Carson J. La Vake, Christian H. Eggers, Juan C. Salazar, and Justin D. Radolf This article is available at OpenCommons@UConn: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/uchcres_articles/182 INFECTION AND IMMUNITY, Jan. 2008, p. 56–70 Vol. 76, No. 1 0019-9567/08/$08.00ϩ0 doi:10.1128/IAI.01039-07 Copyright © 2008, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved. Phagocytosis of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme Disease Spirochete, Potentiates Innate Immune Activation and Induces Apoptosis in Human Monocytesᰔ Adriana R. Cruz,1†‡ Meagan W. Moore,1† Carson J. -

Infectious Disease

INFECTIOUS DISEASE Infectious diseases are caused by germs that are transmitted directly from person to NOTE: person; animal to person (zoonotic The following symbols are used throughout this Community Health Assessment Report to serve only as a simple and quick diseases); from mother to unborn child; or reference for data comparisons and trends for the County. indirectly, such as when a person touches Further analysis may be required before drawing conclusions about the data. a surface that some germs can linger on. The NYSDOH recommends several The apple symbol represents areas in which Oneida County’s status or trend is FAVORABLE or COMPARABLE to its effective strategies for preventing comparison (i.e., NYS, US) or areas/issues identified as infectious diseases,, including: ensuring STRENGTHS. procedures and systems are in place in The magnifying glass symbols represent areas in which Oneida County’s status or trend is UNFAVORABLE to its communities for immunizations to be up to comparison (i.e., NYS, US) or areas/issues of CONCERN date; enabling sanitary practices by or NEED that may warrant further analysis. conveniently located sinks for washing DATA REFERENCES: hands; influencing community resources • All References to tables are in Attachment A – Oneida County Data Book. and cultures to facilitate abstinence and • See also Attachment B – Oneida County Chart Book for risk reduction practices for sexual behavior additional data. and injection drug use, and setting up support systems to ensure medicines are taken as prescribed.453 The reporting of suspect or confirmed communicable diseases is mandated under the New York State Sanitary Code (10NYCRR 2.10). -

Parinaud's Oculoglandular Syndrome

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Case Report Parinaud’s Oculoglandular Syndrome: A Case in an Adult with Flea-Borne Typhus and a Review M. Kevin Dixon 1, Christopher L. Dayton 2 and Gregory M. Anstead 3,4,* 1 Baylor Scott & White Clinic, 800 Scott & White Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA; [email protected] 2 Division of Critical Care, Department of Medicine, University of Texas Health, San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA; [email protected] 3 Medical Service, South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA 4 Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of Texas Health, San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-210-567-4666; Fax: +1-210-567-4670 Received: 7 June 2020; Accepted: 24 July 2020; Published: 29 July 2020 Abstract: Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome (POGS) is defined as unilateral granulomatous conjunctivitis and facial lymphadenopathy. The aims of the current study are to describe a case of POGS with uveitis due to flea-borne typhus (FBT) and to present a diagnostic and therapeutic approach to POGS. The patient, a 38-year old man, presented with persistent unilateral eye pain, fever, rash, preauricular and submandibular lymphadenopathy, and laboratory findings of FBT: hyponatremia, elevated transaminase and lactate dehydrogenase levels, thrombocytopenia, and hypoalbuminemia. His condition rapidly improved after starting doxycycline. Soon after hospitalization, he was diagnosed with uveitis, which responded to topical prednisolone. To derive a diagnostic and empiric therapeutic approach to POGS, we reviewed the cases of POGS from its various causes since 1976 to discern epidemiologic clues and determine successful diagnostic techniques and therapies; we found multiple cases due to cat scratch disease (CSD; due to Bartonella henselae) (twelve), tularemia (ten), sporotrichosis (three), Rickettsia conorii (three), R. -

If Needed You Can Use Two Lines

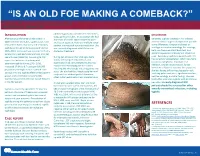

“IS AN OLD FOE MAKING A COMEBACK?” •Eyob Tadesse MD1; Samie Meskele MD1; Ankoor Biswas MD1 •Aurora Health Care, Milwaukee WI. NTRODUCTION abdomen gradually spread to her extremities, DISCUSSION I scalp, palms and soles. In association she had After being on the verge of elimination in shortness of breath, vague abdominal pain Generally, syphilis presents in HIV infected 2000 in the United States, syphilis cases have and loss of appetite, history of multiple sexual patients similar to general population yet with rebounded. Rates of primary and secondary partner, unprotected sex and prostitution. She some differences. Diagnosis is based on syphilis continued to increase overall during was recently diagnosed with HIV but not serologic test and microbiology. For serology, 2005–2013. Increases have occurred primarily started on treatment. both non treponemal antibody test, and among men, and particularly among men has specific treponemal antibody test should be used. Secondary syphilis in patients with HIV sex with men (MSM)(1). According to CDC During her admission her vital signs were has varied skin presentation, which can mimic report the incidence of primary and stable, she had pale conjunctivae, skin cutaneous lymphoma, mycobacterial secondary syphilis during 2015–2016, examination had demonstrated widespread macular and maculopapular skin lesions infection, bacillary angiomatosis, fungal increased 17.6% to 8.7 cases per 100,000 infections or Kaposi’s sarcoma. In our patient, population, the highest rate reported since involving the whole body including palms and soles. She also had thin, fragile scalp hair and she was having diffuse maculopapular rash, 1993(2). HIV and syphilis affect similar patient scalp hair loss without genital ulceration; involving palms and soles, significant hair loss, groups and co-infection is common(3). -

Chlamydia-English

URGENT and PRIVATE IMPORTANT INFORMATION ABOUT YOUR HEALTH DIRECTIONS FOR SEX PARTNERS OF PERSONS WITH CHLAMYDIA PLEASE READ THIS VERY CAREFULLY Your sex partner has recently been treated for chlamydia. Chlamydia is a sexually transmitted disease (STD) that you can get from having any kind of sex (oral, vaginal, or anal) with a person who already has it. You may have been exposed. The good news is that it’s easily treated. You are being given a medicine called azithromycin (sometimes known as “Zithromax”) to treat your chlamydia. Your partner may have given you the actual medicine, or a prescription that you can take to a pharmacy. These are instructions for how to take azithromycin. The best way to take care of this infection is to see your own doctor or clinic provider right away. If you can’t get to a doctor in the next several days, you should take the azithromycin. Even if you decide to take the medicine, it is very important to see a doctor as soon as you can, to get tested for other STDs. People can have more than one STD at the same time. Azithromycin will not cure other sexually transmitted infections. Having STDs can increase your risk of getting HIV, so make sure to also get an HIV test. SYMPTOMS Some people with chlamydia have symptoms, but most do not. Symptoms may include pain in your testicles, pelvis, or lower part of your belly. You may also have pain when you urinate or when having sex. Many people with chlamydia do not know they are infected because they feel fine. -

Treating Opportunistic Infections Among HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Recommendations and Reports December 17, 2004 / Vol. 53 / No. RR-15 Treating Opportunistic Infections Among HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents Recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association/ Infectious Diseases Society of America INSIDE: Continuing Education Examination department of health and human services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention MMWR CONTENTS The MMWR series of publications is published by the Epidemiology Program Office, Centers for Disease Introduction......................................................................... 1 Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of How To Use the Information in This Report .......................... 2 Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA 30333. Effect of Antiretroviral Therapy on the Incidence and Management of OIs .................................................... 2 SUGGESTED CITATION Initiation of ART in the Setting of an Acute OI Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treating (Treatment-Naïve Patients) ................................................. 3 Management of Acute OIs in the Setting of ART .................. 4 opportunistic infections among HIV-infected adults and When To Initiate ART in the Setting of an OI ........................ 4 adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Special Considerations During Pregnancy ........................... 4 Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association/ Disease Specific Recommendations .................................... -

Compendium of Measures to Control Chlamydia Psittaci Infection Among

Compendium of Measures to Control Chlamydia psittaci Infection Among Humans (Psittacosis) and Pet Birds (Avian Chlamydiosis), 2017 Author(s): Gary Balsamo, DVM, MPH&TMCo-chair Angela M. Maxted, DVM, MS, PhD, Dipl ACVPM Joanne W. Midla, VMD, MPH, Dipl ACVPM Julia M. Murphy, DVM, MS, Dipl ACVPMCo-chair Ron Wohrle, DVM Thomas M. Edling, DVM, MSpVM, MPH (Pet Industry Joint Advisory Council) Pilar H. Fish, DVM (American Association of Zoo Veterinarians) Keven Flammer, DVM, Dipl ABVP (Avian) (Association of Avian Veterinarians) Denise Hyde, PharmD, RP Preeta K. Kutty, MD, MPH Miwako Kobayashi, MD, MPH Bettina Helm, DVM, MPH Brit Oiulfstad, DVM, MPH (Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists) Branson W. Ritchie, DVM, MS, PhD, Dipl ABVP, Dipl ECZM (Avian) Mary Grace Stobierski, DVM, MPH, Dipl ACVPM (American Veterinary Medical Association Council on Public Health and Regulatory Veterinary Medicine) Karen Ehnert, and DVM, MPVM, Dipl ACVPM (American Veterinary Medical Association Council on Public Health and Regulatory Veterinary Medicine) Thomas N. Tully JrDVM, MS, Dipl ABVP (Avian), Dipl ECZM (Avian) (Association of Avian Veterinarians) Source: Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery, 31(3):262-282. Published By: Association of Avian Veterinarians https://doi.org/10.1647/217-265 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1647/217-265 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. -

Canine Lyme Borrelia

Canine Lyme Borrelia Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria are the cause of Lyme disease in humans and animals. They can be visualized by darkfild microscopy as "corkscrew-shaped" motile spirochetes (400 x). Inset: The black-legged tick, lxodes scapularis (deer tick), may carry and transmit Borrelia burgdorferi to humans and animals during feeding, and thus transmit Lyme disease. Samples: Blood EDTA-blood as is, purple-top tubes or EDTA-blood preserved in sample buffer (preferred) Body fluids Preserved in sample buffer Notes: Send all samples at room temperature, preferably preserved in sample buffer MD Submission Form Interpretation of PCR Results: High Positive Borrelia spp. infection (interpretation must be correlated to (> 500 copies/ml swab) clinical symptoms) Low Positive (<500 copies/ml swab) Negative Borrelia spp. not detected Lyme Borreliosis Lyme disease is caused by spirochete bacteria of a subgroup of Borrelia species, called Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Only one species, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, is known to be present in the USA, while at least four pathogenic species, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, B. garinii, B. japonica have been isolated in Europe and Asia (Aguero- Rosenfeld et al., 2005). B. burgdorferi sensu lato organisms are corkscrew-shaped, motile, microaerophilic bacteria of the order Spirochaetales. Hard-shelled ticks of the genus Ixodes transmit B. burgdorferi by attaching and feeding on various mammalian, avian, and reptilian hosts. In the northeastern states of the US Ixodes scapularis, the black-legged deer tick, is the predominant vector, while at the west coast Lyme borreliosis is maintained by a transmission cycle which involves two tick species, I. -

Genetic Diversity of Bartonella Species in Small Mammals in the Qaidam

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Genetic diversity of Bartonella species in small mammals in the Qaidam Basin, western China Huaxiang Rao1, Shoujiang Li3, Liang Lu4, Rong Wang3, Xiuping Song4, Kai Sun5, Yan Shi3, Dongmei Li4* & Juan Yu2* Investigation of the prevalence and diversity of Bartonella infections in small mammals in the Qaidam Basin, western China, could provide a scientifc basis for the control and prevention of Bartonella infections in humans. Accordingly, in this study, small mammals were captured using snap traps in Wulan County and Ge’ermu City, Qaidam Basin, China. Spleen and brain tissues were collected and cultured to isolate Bartonella strains. The suspected positive colonies were detected with polymerase chain reaction amplifcation and sequencing of gltA, ftsZ, RNA polymerase beta subunit (rpoB) and ribC genes. Among 101 small mammals, 39 were positive for Bartonella, with the infection rate of 38.61%. The infection rate in diferent tissues (spleens and brains) (χ2 = 0.112, P = 0.738) and gender (χ2 = 1.927, P = 0.165) of small mammals did not have statistical diference, but that in diferent habitats had statistical diference (χ2 = 10.361, P = 0.016). Through genetic evolution analysis, 40 Bartonella strains were identifed (two diferent Bartonella species were detected in one small mammal), including B. grahamii (30), B. jaculi (3), B. krasnovii (3) and Candidatus B. gerbillinarum (4), which showed rodent-specifc characteristics. B. grahamii was the dominant epidemic strain (accounted for 75.0%). Furthermore, phylogenetic analysis showed that B. grahamii in the Qaidam Basin, might be close to the strains isolated from Japan and China. -

Pdf/Bookshelf NBK368467.Pdf

BMJ 2019;365:l4159 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4159 (Published 28 June 2019) Page 1 of 11 Practice BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.l4159 on 28 June 2019. Downloaded from PRACTICE CLINICAL UPDATES Syphilis OPEN ACCESS Patrick O'Byrne associate professor, nurse practitioner 1 2, Paul MacPherson infectious disease specialist 3 1School of Nursing, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario K1H 8M5, Canada; 2Sexual Health Clinic, Ottawa Public Health, Ottawa, Ontario K1N 5P9; 3Division of Infectious Diseases, Ottawa Hospital General Campus, Ottawa, Ontario What you need to know Box 1: Symptoms of syphilis by stage of infection (see fig 1) • Incidence rates of syphilis have increased substantially around the Primary world, mostly affecting men who have sex with men and people infected • Symptoms appear 10-90 days (mean 21 days) after exposure with HIV http://www.bmj.com/ • Main symptom is a <2 cm chancre: • Have a high index of suspicion for syphilis in any sexually active patient – Progresses from a macule to papule to ulcer over 7 days with genital lesions or rashes – Painless, solitary, indurated, clean base (98% specific, 31% sensitive) • Primary syphilis classically presents as a single, painless, indurated genital ulcer (chancre), but this presentation is only 31% sensitive; – On glans, corona, labia, fourchette, or perineum lesions can be painful, multiple, and extra-genital – A third are extragenital in men who have sex with men and in women • Diagnosis is usually based on serology, using a combination of treponemal and non-treponemal tests. Syphilis remains sensitive to • Localised painless adenopathy benzathine penicillin G Secondary on 24 September 2021 by guest.