Archived Content Contenu Archivé

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..39 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 40th PARLIAMENT, 3rd SESSION 40e LÉGISLATURE, 3e SESSION Journals Journaux No. 2 No 2 Thursday, March 4, 2010 Le jeudi 4 mars 2010 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE DAILY ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AFFAIRES COURANTES ORDINAIRES TABLING OF DOCUMENTS DÉPÔT DE DOCUMENTS Pursuant to Standing Order 32(2), Mr. Lukiwski (Parliamentary Conformément à l'article 32(2) du Règlement, M. Lukiwski Secretary to the Leader of the Government in the House of (secrétaire parlementaire du leader du gouvernement à la Chambre Commons) laid upon the Table, — Government responses, des communes) dépose sur le Bureau, — Réponses du pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), to the following petitions: gouvernement, conformément à l’article 36(8) du Règlement, aux pétitions suivantes : — Nos. 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, — nos 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, 402- 402-1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 402- 402-1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 and 402-1513 1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 et 402-1513 au sujet du concerning the Employment Insurance Program. — Sessional régime d'assurance-emploi. — Document parlementaire no 8545- Paper No. 8545-403-1-01; 403-1-01; — Nos. 402-1129, 402-1174 and 402-1268 concerning national — nos 402-1129, 402-1174 et 402-1268 au sujet des parcs parks. — Sessional Paper No. 8545-403-2-01; nationaux. — Document parlementaire no 8545-403-2-01; — Nos. -

Canada Gazette, Part I

EXTRA Vol. 140, No. 3 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 140, no 3 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 3, 2006 OTTAWA, LE VENDREDI 3 FÉVRIER 2006 CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 39th general election Rapport de députés(es) élus(es) à la 39e élection générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Canada Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’article 317 Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, have been de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, dans l’ordre received of the election of Members to serve in the House of ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élection de députés(es) à Commons of Canada for the following electoral districts: la Chambre des communes du Canada pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral Districts Members Circonscriptions Députés(es) South Surrey—White Rock— Russ Hiebert Surrey-Sud—White Rock— Russ Hiebert Cloverdale Cloverdale Kitchener—Conestoga Harold Glenn Albrecht Kitchener—Conestoga Harold Glenn Albrecht Wild Rose Myron Thompson Wild Rose Myron Thompson West Vancouver—Sunshine Blair Wilson West Vancouver—Sunshine Blair Wilson Coast—Sea to Sky Country Coast—Sea to Sky Country Nepean—Carleton Pierre Poilievre Nepean—Carleton Pierre Poilievre Whitby—Oshawa Jim Flaherty Whitby—Oshawa Jim Flaherty Saint-Hyacinthe—Bagot Yvan Loubier Saint-Hyacinthe—Bagot Yvan Loubier Sudbury Diane Marleau Sudbury Diane Marleau Toronto—Danforth -

Mass Cancellations Put Artists' Livelihoods at Risk; Arts Organizations in Financial Distress

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau March 17, 2020 Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland The Honourable Steven Guilbeault The Honourable William Francis Morneau Minister of Canadian Heritage Minister of Finance The Honourable Mona Fortier The Honourable Navdeep Bains Minister of Middle-Class Prosperity Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry Associate Minister of Finance The Honourable Mélanie Joly Minister of Economic Development and Official Languages Re: Mass cancellations put artists’ livelihoods at risk; arts organizations in financial distress Dear Prime Minister Trudeau; Deputy Prime Minister Freeland; and Ministers Guilbeault, Morneau, Fortier, Joly, and Bains, We write as the leadership of Opera.ca, the national association for opera companies and professionals in Canada. In light of recent developments around COVID-19 and the waves of cancellations as a result of bans on mass gatherings, Opera.ca is urgently requesting federal aid on behalf of the Canadian opera sector and its artists -- its most essential and vulnerable people -- while pledging its own emergency support for artists in desperate need. Opera artists are the heart of the opera sector, and their economic survival is in jeopardy. In response to the dire need captured by a recent survey conducted by Opera.ca, the board of directors of Opera.ca today voted for an Opera Artists Emergency Relief Fund to be funded by the association. Further details will be announced shortly. Of the 14 professional opera companies in Canada, almost all have cancelled their current production and some the remainder of the season. This is an unprecedented crisis with long-reaching implications for the entire Canadian opera sector. -

Brief Submitted to the Committee

Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs Sixth Floor, 131 Queen Street House of Commons Ottawa ON K1A 0A6 Canada November 27, 2020 Please accept this brief for the Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs study of support for Indigenous communities, businesses, and individuals through a second wave of Covid-19. SITUATION Since March 2020, James Smith Cree Nation (JSCN) and the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN), have made requests to Canada for funding support for a First Nations led and managed solution to address our urgent and emergency need for Personal Protective Equipment in order to ensure the safety and wellbeing of our communities in the face of COVID-19. We have engaged exhaustive correspondence and communications about these proposals with: Rt. Hon. Justin Trudeau, Hon. Chrystia Freeland, Hon. Marc Miller, Mr. Mike Burton, Hon. Carolyn Bennett, and ISC Regional officials Jocelyn Andrews, Rob Harvey and Bonnie Rushowick. Despite extensive consultations and discussions with the department and minister’s office, we have experienced significant delays and denials from Canada to support these urgently needed and emergency proposals. This has been well documented since May, with particular reference to ‘Indigenous Services Moving Goalposts on First Nations PPE’, CBC News, September 11, 2020 (https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/first-nations-ppe-proposal-1.5721249). The failed funding and departmental dysfunction have resulted in significant outbreaks which are occurring across our regions. By Canada’s own admission on November 29, COVID-19 is now four times (4x) worse in First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities than during the first wave which occurred from March through May 2020. -

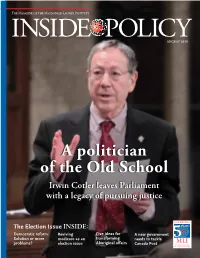

The August 2015 Issue of Inside Policy

AUGUST 2015 A politician of the Old School Irwin Cotler leaves Parliament with a legacy of pursuing justice The Election Issue INSIDE: Democratic reform: Reviving Five ideas for A new government Solution or more medicare as an transforming needs to tackle problems? election issue Aboriginal affairs Canada Post PublishedPublished by by the the Macdonald-Laurier Macdonald-Laurier Institute Institute PublishedBrianBrian Lee Lee Crowley, byCrowley, the Managing Macdonald-LaurierManaging Director,Director, [email protected] [email protected] Institute David Watson,JamesJames Anderson,Managing Anderson, Editor ManagingManaging and Editor, Editor,Communications Inside Inside Policy Policy Director Brian Lee Crowley, Managing Director, [email protected] James Anderson,ContributingContributing Managing writers:writers: Editor, Inside Policy Past contributors ThomasThomas S. AxworthyS. Axworthy ContributingAndrewAndrew Griffith writers: BenjaminBenjamin Perrin Perrin Thomas S. AxworthyDonald Barry Laura Dawson Stanley H. HarttCarin Holroyd Mike Priaro Peggy Nash DonaldThomas Barry S. Axworthy StanleyAndrew H. GriffithHartt BenjaminMike PriaroPerrin Mary-Jane Bennett Elaine Depow Dean Karalekas Linda Nazareth KenDonald Coates Barry PaulStanley Kennedy H. Hartt ColinMike Robertson Priaro Carolyn BennettKen Coates Jeremy Depow Paul KennedyPaul Kennedy Colin RobertsonGeoff Norquay Massimo Bergamini Peter DeVries Tasha Kheiriddin Benjamin Perrin Brian KenLee Crowley Coates AudreyPaul LaporteKennedy RogerColin Robinson Robertson Ken BoessenkoolBrian Lee Crowley Brian -

PRISM::Advent3b2 17.25

House of Commons Debates VOLUME 147 Ï NUMBER 187 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 41st PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Monday, March 23, 2015 Speaker: The Honourable Andrew Scheer CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 12135 HOUSE OF COMMONS Monday, March 23, 2015 The House met at 11 a.m. In March, barely 30 days before that fateful day of April 30, the Khmer Rouge forces had effectively surrounded Phnom Penh, the Cambodian capital. The American ambassador, Ambassador Dean, had begun preparations for the final pullout of embassy staff and Prayers Americans and third-country nationals, which took place on April 12, and which led to the eventual Cambodian genocide, the brutal Ï (1100) murder of more than two million Cambodians, and a dark five years in that Southeast Asian country. [Translation] VACANCY Barely three weeks later, the United States ambassador in Saigon, OTTAWA WEST—NEPEAN Ambassador Martin, decided it was time to end the American presence in that country. The musical strains of White Christmas The Speaker: It is my duty to inform the House that a vacancy were heard on April 29, and on armed forces radio in Saigon a voice has occurred in the representation, namely. said it is 110 degrees in Saigon and rising. This was the signal to all [English] Americans, to all third-country nationals, to all Vietnamese who had worked in various ways for the United States over the previous three Mr. Baird, member for the electoral district of Ottawa West— decades, to assemble at evacuation points and to leave the country. -

Support the Bill to Ban Canada's Asbestos Exports Send Your Letter to All Party Leaders

Support the bill to ban Canada's asbestos exports Send your letter to all party leaders Asbestos kills and goes on killing for generations. It is impossible to manage asbestos safely and so all industrialized countries have banned or stopped using all forms of asbestos. But Canada is one of the world’s largest exporters of asbestos, mostly to poor countries. That’s why today, June 1, Member of Parliament Nathan Cullen (NDP, Skeena-Bulkley Valley) introduced a Private Member’s Bill to ban the mining and export of asbestos. It deserves everyone’s support. Send your letter to party leaders to urge them to support "An Act to amend the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (asbestos)." We no longer use asbestos in Canada. Instead, we export it to developing countries, telling them it is a safe, desirable product for their homes and schools. The World Health Organization estimates that 125 million workers worldwide are exposed to asbestos every year and more than 90,000 workers die as a result of their exposure. This heartless double standard must stop. The Bill was inspired by three remarkable students from Smithers, a small town in north-west British Columbia, who are determined to make sure Canada is no longer disgraced by its dirty exports. Write to Party leaders to tell them to support the Bill, and to listen to the message of the students, of health organizations and of the worldwide trade union movement. Do the right thing. Help stop Canada’s export of asbestos. Thank you for speaking up for human rights! Kathleen, Peggy, Pauline, Becky Where the political parties stand: • The NDP and the Green Party support the banning of asbestos. -

September 15, 2020 the Hon. Pierre Poilievre Shadow Minister, Finance

September 15, 2020 The Hon. Pierre Poilievre Shadow Minister, Finance Conservative Party of Canada Member of Parliament, Carleton Dear Mr. Poilievre, On behalf of the Ontario Federation of Agriculture (OFA), we would like to congratulate you on being appointed the Shadow Minister of Finance for the Conservative Party of Canada. We know your leadership abilities will be a great asset in your new role. We look forward to working together with you and your colleagues to unlock continued economic growth opportunities for Ontario’s agri-food sector and drive a healthy economy that benefits all Ontarians and contributes to all Canadians. The COVID-19 pandemic has created a new reality for all Ontarians and Canadians as the changes and challenges to our social and economic environment continue to mount each day. Ontarians rely on the agri-food system to ensure they have steady and reliable access to safe, healthy and affordable food products. Farmers are well-known for their resilience and perseverance. But, even before the COVID-19 crisis, farmers were coping with a difficult year that included multiple rail disruptions, a shortage of meat processing capacity and volatile global trade and market access. Ontario’s diverse and innovative agri-food industry feeds our population, continues to provide positive environmental and climate change benefits, fuels our rural communities and serves as an economic engine for the provincial economy, generating more than 860,000 jobs and contributing more than $47 billion to Ontario’s annual GDP. From farmers to our diverse food processing industry, our agri-food sector is a powerhouse of possibilities. -

Core 1..146 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 8.00)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 140 Ï NUMBER 098 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 38th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, May 13, 2005 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 5957 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, May 13, 2005 The House met at 10 a.m. Parliament on February 23, 2005, and Bill C-48, an act to authorize the Minister of Finance to make certain payments, shall be disposed of as follows: 1. Any division thereon requested before the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, shall be deferred to that time; Prayers 2. At the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, all questions necessary for the disposal of the second reading stage of (1) Bill C-43 and (2) Bill C-48 shall be put and decided forthwith and successively, Ï (1000) without further debate, amendment or deferral. [English] Ï (1010) MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE The Speaker: Does the hon. government House leader have the The Speaker: I have the honour to inform the House that a unanimous consent of the House for this motion? message has been received from the Senate informing this House Some hon. members: Agreed. that the Senate has passed certain bills, to which the concurrence of this House is desired. Some hon. members: No. Mr. Jay Hill (Prince George—Peace River, CPC): Mr. -

Cabinet Committee Mandate and Membership

Cabinet Committee Mandate and Membership Current as of September 28, 2020 The Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance and the Minister of Middle Class Prosperity and Associate Minister of Finance are ex-officio members of Committees where they are not shown as standing members. The Honourable James Gordon Carr, P.C. will be invited to attend committee meetings at the request of Committee Chairs. Cabinet Committee on Agenda, Results and Communications Addresses major issues affecting national unity and the strategic agenda of the government, tracks progress on the government’s priorities, coordinates the implementation of the government’s overall agenda, and considers strategic communications issues. Chair: The Rt. Hon. Justin P. J. Trudeau Vice-Chair: The Hon. Chrystia Freeland Members The Hon. Navdeep Singh Bains The Hon. James Gordon Carr The Hon. Mélanie Joly The Hon. Dominic LeBlanc The Hon. Carla Qualtrough The Hon. Pablo Rodriguez The Honourable James Gordon Carr, the Special Representative for the Prairies, will be invited to attend meetings. Treasury Board Acts as the government’s management board. Provides oversight of the government’s financial management and spending, as well as oversight on human resources issues. Provides oversight on complex horizontal issues such as defence procurement and modernizing the pay system. Responsible for reporting to Parliament. Is the employer for the public service, and establishes policies and common standards for administrative, personnel, financial, and organizational practices across government. Fulfills the role of the Committee of Council in approving regulatory policies and regulations, and most orders-in-council. Chair: The Hon. Jean-Yves Duclos Vice-Chair: The Hon. -

Letter to Prime Minister Trudeau Re Radioactive Waste Policy

The Right Honourable Justin Trudeau September 19 2017 Prime Minister of Canada Dear Prime Minister Trudeau: Canada is at the dawn of a new era: the Age of Nuclear Waste. Yet this country has no official policy regarding the long-term management of any radioactive wastes other than irradiated nuclear fuel. A federal policy on radioactive wastes other than irradiated fuel is urgently needed. The absence of such a policy in effect gives a green light for the approval of three ill-considered projects to abandon long-lived radioactive wastes at sites very close to major bodies of water – wastes that will remain hazardous for hundreds of thousands of years. One is a gigantic multi- story mound, on the surface at Chalk River, one kilometre from the Ottawa River, meant to permanently house up to a million cubic metres of mixed radioactive wastes. The other two projects involve the in-situ abandonment of the long-lived radioactive remains from two defunct nuclear reactors – the NPD reactor at Rolphton on the Ottawa River, and the WR-1 reactor at Pinawa on the Winnipeg River. These projects pose a threat to future generations, and they set a dreadful example for other countries looking to Canada for socially and environmentally acceptable policies and practices. All three projects involve radioactive wastes that are the sole responsibility of the government of Canada; yet in each case, the projects have been conceived by a private consortium of multinational corporations hired by the previous federal government under a time-limited contract. The previous government also ensured that the approvals process for all three projects is entirely in the hands of the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC), a body whose independence has been challenged from many quarters. -

Core 1..31 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 8.00)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 38th PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 38e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 134 No 134 Friday, October 7, 2005 Le vendredi 7 octobre 2005 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE GOVERNMENT ORDERS ORDRES ÉMANANT DU GOUVERNEMENT The House resumed consideration of the motion of Mr. Mitchell La Chambre reprend l'étude de la motion de M. Mitchell (Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food), seconded by Mr. Brison (ministre de l'Agriculture et de l'Agroalimentaire), appuyé par M. (Minister of Public Works and Government Services), — That Bill Brison (ministre des Travaux publics et des Services S-38, An Act respecting the implementation of international trade gouvernementaux), — Que le projet de loi S-38, Loi concernant commitments by Canada regarding spirit drinks of foreign la mise en oeuvre d'engagements commerciaux internationaux pris countries, be now read a second time and referred to the par le Canada concernant des spiritueux provenant de pays Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food. étrangers, soit maintenant lu une deuxième fois et renvoyé au Comité permanent de l'agriculture et de l'agroalimentaire. The debate continued. Le débat se poursuit. The question was put on the motion and it was agreed to. La motion, mise aux voix, est agréée. Accordingly, Bill S-38, An Act respecting the implementation En conséquence, le projet de loi S-38, Loi concernant la mise en of international trade commitments by Canada regarding spirit oeuvre d'engagements commerciaux internationaux pris par le drinks of foreign countries, was read the second time and referred Canada concernant des spiritueux provenant de pays étrangers, est to the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food.