Cmi Brief 2018:9 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statoil-Environment Impact Study for Block 39

Technical Sheet Title: Environmental Impact Study for the Block 39 Exploratory Drilling Project. Client: Statoil Angola Block 39 AS Belas Business Park, Edifício Luanda 3º e 4º andar, Talatona, Belas Telefone: +244-222 640900; Fax: +244-222 640939. E-mail: [email protected] www.statoil.com Contractor: Holísticos, Lda. – Serviços, Estudos & Consultoria Rua 60, Casa 559, Urbanização Harmonia, Benfica, Luanda Telefone: +244-222 006938; Fax: +244-222 006435. E-mail: [email protected] www.holisticos.co.ao Date: August 2013 Environmental Impact Study for the Block 39 Exploratory Drilling Project TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2. PROJECT SITE .............................................................................................................................. 1-4 1.3. PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THE EIS .................................................................................................... 1-5 1.4. AREAS OF INFLUENCE .................................................................................................................... 1-6 1.4.1. Directly Affected area ...................................................................................................... 1-7 1.4.2. Area of direct influence .................................................................................................. -

Taxonomy of Tropical West African Bivalves V. Noetiidae

Bull. Mus. nati. Hist, nat., Paris, 4' sér., 14, 1992, section A, nos 3-4 : 655-691. Taxonomy of Tropical West African Bivalves V. Noetiidae by P. Graham OLIVER and Rudo VON COSEL Abstract. — Five species of Noetiidae are described from tropical West Africa, defined here as between 23° N and 17°S. The Noetiidae are represented by five genera, and four new taxa are introduced : Stenocista n. gen., erected for Area gambiensis Reeve; Sheldonella minutalis n. sp., Striarca lactea scoliosa n. subsp. and Striarca lactea epetrima n. subsp. Striarca lactea shows considerable variation within species. Ecological factors and geographical clines are invoked to explain some of this variation but local genetic isolation could not be excluded. The relationships of the shallow water West African noetiid species are analysed and compared to the faunas of the Mediterranean, Caribbean, Panamic and Indo- Pacific regions. Stenocista is the only genus endemic to West Africa. A general discussion on the relationships of all the shallow water West African Arcoidea is presented. The level of generic endemism is low and there is clear evidence of circumtropical patterns of similarity between species. The greatest affinity is with the Indo-Pacific but this pattern is not consistent between subfamilies. Notably the Anadarinae have greatest similarity to the Panamic faunal province. Résumé. — Description de cinq espèces de Noetiidae d'Afrique occidentale tropicale, ici définie entre 23° N et 17° S. Les Noetiidae sont représentés par cinq genres. Quatre taxa nouveaux sont décrits : Stenocista n. gen. (espèce-type Area gambiensis Reeve) ; Sheldonella minutalis n. sp., Striarca lactea scoliosa n. -

MURKY WATERS Why the Cholera Epidemic in Luanda

MURKY WATERS Why the cholera epidemic in Luanda (Angola) was a disaster waiting to happen MSF May 2006 ! !1 Executive Summary Since February 2006, Luanda is going through its worst ever cholera epidemic, with an average of 500 new cases per day. The outbreak has also rapidly spread to the provinces and to date, 11 of the 18 provinces are reporting cases. The population of Luanda has doubled in the last 10 years, and most of this growth is concentrated in slums where the living conditions are appalling. Despite impressive revenues from oil and diamonds, there has been virtually no investment in basic services since the 1970s and only a privileged minority of the people living in Luanda have access to running water. The rest of the population get most of their water from a huge network of water trucks that collect water from two main points (Kifangondo at Bengo river in Cacuaco and Kikuxi at Kuanza river in Viana) and then distribute it all over town at a considerable profit. Water, the most basic of commodities, is a lucrative and at times complex business in Luanda, with prices that vary depending on demand. Without sufficient quantities of water, and given the lack of proper drainage and rubbish collection, disease is rampant in the vast slums. This disastrous water and sanitation situation makes it virtually impossible to contain the rapid spread of the outbreak. Médecins Sans Frontières is already working in ten cholera treatment structures, and may open more in the coming weeks. Out of the 17,500 patients reported in Luanda (the figure for all of Angola is 34,000), more than14,000 have been treated in MSF centres Despite significant efforts to ensure that patients have access to treatment, very little has been done to prevent hundreds more from becoming infected. -

Payment Systems in Angola

THE PAYMENT SYSTEM IN ANGOLA Table of Contents OVERVIEW OF THE NATIONAL PAYMENT SYSTEM IN ANGOLA ............................... 5 1. INSTITUTIONAL ASPECTS .............................................................................................. 5 1.1 General legal aspects ................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Roles of financial intermediaries that provide payment services ........................... 6 1.3 Roles of the central bank ............................................................................................ 6 1.4 Roles of other private sector and public sector bodies ............................................ 7 2. SUMMARY INFORMATION ON PAYMENT MEDIA USED BY NON-BANKS ....... 7 2.1 Cash payments ............................................................................................................ 7 2.2 Non-cash payments ..................................................................................................... 8 2.2.1 Cheques ............................................................................................................... 8 2.2.2 Credit transfer orders ......................................................................................... 8 2.2.3 Standing/stop order drafts .................................................................................. 8 2.2.4 Other documents to be cleared ........................................................................... 8 2.2.5 Other transfer documents .................................................................................. -

Angola-Luanda-Bita-Water-Supply

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: 137066-AO Public Disclosure Authorized INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED GUARANTEE Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF UP TO US$500 MILLION IN SUPPORT OF THE REPUBLIC OF ANGOLA FOR THE LUANDA BITA WATER SUPPLY GUARANTEE PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized June 11, 2019 Water Global Practice Africa Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective April 30 , 2019) Currency Unit = Angolan Kwanza (AKZ) AKZ 323.08 = US$1 FISCAL YEAR January 1-December 31 Regional Vice President: Hafez Ghanem Country Director: Elisabeth Huybens Senior Global Practice Director: Jennifer Sara Practice Managers: Maria Angelica Sotomayor Araujo, Sebnem Erol Madan Task Team Leaders: Pier Francesco Mantovani, Satheesh Kumar Sundararajan i ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ACS Additional Cash Support AKZ Angolan Kwanza AML/CFT Anti-Money Laundering / Combating the Financing of Terrorism AQR Asset Quality Review ATI African Trade Insurance Agency BNA Central Bank of Angola bpifrance French Public Investment Bank (Banque Publique d’Investissement) C-ESMP Contractor Environmental and Social Management Plan CD Distribution Center (Centro de Distribução) CE Citizen Engagement CLO Community Liaison Officer CPF Country -

Urban Poverty in Luanda, Angola CMI Report, Number 6, April 2018

NUMBER 6 CMI REPORT APRIL 2018 AUTHORS Inge Tvedten Gilson Lázaro Urban poverty Eyolf Jul-Larsen Mateus Agostinho in Luanda, COLLABORATORS Nelson Pestana Angola Iselin Åsedotter Strønen Cláudio Fortuna Margareht NangaCovie Urban poverty in Luanda, Angola CMI Report, number 6, April 2018 Authors Inge Tvedten Gilson LázAro Eyolf Jul-Larsen Mateus Agostinho Collaborators Nelson PestanA Iselin Åsedotter Strønen Cláudio FortunA MargAreht NAngACovie ISSN 0805-505X (print) ISSN 1890-503X (PDF) ISBN 978-82-8062-697-4 (print) ISBN 978-82-8062-698-1 (PDF) Cover photo Gilson LázAro CMI Report 2018:06 Urban poverty in Luanda, Angola www.cmi.no Table of content 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Poverty in AngolA ................................................................................................................................ 4 1.2 AnalyticAl ApproAch ............................................................................................................................. 6 1.3 Methodologies ..................................................................................................................................... 7 1.4 The project sites .................................................................................................................................. 9 2 Structural context ....................................................................................................................................... -

ANGOLA: FLOODS 30 January 2007

DREF Bulletin no. MDRAO002 Glide no. FF-2007-000020-AGO ANGOLA: FLOODS 30 January 2007 The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its millions of volunteers are active in over 185 countries. In Brief This DREF Bulletin is being issued based on the situation described below reflecting the information available at this time. CHF 90,764 (USD 74,397 or EUR 56,463) has been allocated from the Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to respond to the needs in this operation. This operation is expected to be implemented over 5 months, and will be completed by 30 June 2007; a Final Report will be made available three months after the end of the operation. Unearmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. <Click here to go directly to the attached map> This operation is aligned with the International Federation's Global Agenda, which sets out four broad goals to meet the Federation's mission to "improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity". Global Agenda Goals: • Reduce the numbers of deaths, injuries and impact from disasters. • Reduce the number of deaths, illnesses and impact from diseases and public health emergencies. • Increase local community, civil society and Red Cross Red Crescent capacity to address the most urgent situations of vulnerability. • Reduce intolerance, discrimination and social exclusion and promote respect for diversity and human dignity. Background and current situation Since 21 January 2007, Angola’s capital city Luanda has been experiencing heavy rains which caused damage to infrastructure and displaced thousands of people. -

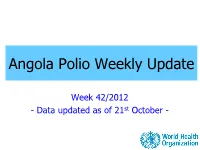

Weekly Polio Eradication Update

Angola Polio Weekly Update Week 42/2012 - Data updated as of 21st October - * Data up to Oct 21 Octtoup Data * Reported WPV cases by month of onset and SIAs, and SIAs, of onset WPV cases month by Reported st 2012 2008 13 12 - 11 2012* 10 9 8 7 WPV 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Jul-08 Jul-09 Jul-10 Jul-11 Jul-12 Jan-08 Jun-08 Oct-08 Jan-09 Jun-09 Oct-09 Jan-10 Jun-10 Oct-10 Jan-11 Jun-11 Oct-11 Jan-12 Jun-12 Feb-08 Mar-08 Apr-08 Feb-09 Mar-09 Apr-09 Feb-10 Mar-10 Apr-10 Fev-11 Mar-11 Apr-11 Feb-12 Mar-12 Apr-12 Sep-08 Nov-08 Dec-08 Sep-09 Nov-09 Dec-09 Sep-10 Nov-10 Dez-10 Sep-11 Nov-11 Dec-11 Sep-12 May-08 Aug-08 May-09 Aug-09 May-10 Aug-10 May-11 Aug-11 May-12 Aug-12 Wild 1 Wild 3 mOPV1 mOPV3 tOPV Angola bOPV AFP Case Classification Status 22 Oct 2011 to 21 Oct 2012 290 Reported Cases 239 3 43 5 0 Discarded Not AFP Pending Compatible Wild Polio Classification 27 0 16 Pending Pending Pending final Lab Result ITD classification AFP Case Classification by Week of Onset 22 Oct 2011 to 21 Oct 2012 16 - 27 pending lab results - 16 pending final classification 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 43 44 45 46 48 49 50 51 52 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 Pending_Lab Pending_Final Class Positive Compatible Discarded Not_AFP National AFP Surveillance Performance Twelve Months Rolling-period, 2010-2012 22 Oct 2010 to 21 Oct 2011 22 Oct 2011 to 21 Oct 2012 NP AFP ADEQUACY NP AFP ADEQUACY PROVINCE SURV_INDEX PROVINCE SURV_INDEX RAT E RAT E RAT E RAT E BENGO 4.0 100 4.0 BENGO 3.0 75 2.3 BENGUELA 2.7 -

Strengthening Angolan Systems for Health (SASH) Angola Final Report

Strengthening Angolan Systems for Health (SASH) Angola Final Report October 1, 2011– April 30, 2017 Submitted: June 30, 2017 Produced for review by: United States Agency for International Development, USAID Cooperative Agreement No. AID-654-A-11-00001 Prepared by: Jhpiego in collaboration with Management Sciences for Health This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Jhpiego Corporation or the Angola SASH program and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Table of Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms ......................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................... vii Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... ix Major Accomplishments .................................................................................................................x Background and Approach ............................................................................................................ 1 Key Changes in SASH’s SOW ........................................................................................................ 2 Geographic Focus ......................................................................................................................... -

The Angolan Revolution, Vol. I: the Anatomy of an Explosion (1950-1962)

The Angolan revolution, Vol. I: the anatomy of an explosion (1950-1962) http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp2b20033 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The Angolan revolution, Vol. I: the anatomy of an explosion (1950-1962) Author/Creator Marcum, John Publisher Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press (Cambridge) Date 1969 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Angola, Portugal, United States, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Congo, Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Coverage (temporal) 1950 - 1962 Source Northwestern University Libraries, Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, 967.3 M322a, v. -

Urban Governance and Turning African Cities Around: Luanda Case

Advancing research excellence for governance and public policy in Africa PASGR Working Paper 018 Urban Governance and Turning African CiƟes Around: Luanda Case Study Croese, Sylvia University of Cape Town August, 2016 This report was produced in the context of a mul‐country study on the ‘Urban Governance and Turning African Cies Around ’, generously supported by the UK Department for Internaonal Development (DFID) through the Partnership for African Social and Governance Research (PASGR). The views herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those held by PASGR or DFID. Author contact informaƟon: Sylvia Croese University of Cape Town [email protected] Suggested citaƟon: Croese, S. (2016). Urban Governance and Turning African CiƟes Around: Luanda Case Study. Partnership for African Social and Governance Research Working Paper No. 018, Nairobi, Kenya. Acknowledgements: I would like to acknowledge the research assistance for this study from João Francisco Pinto Domingos, head of the urban governance unit of Development Workshop Angola, and the support of its director, Allan Cain, and the head of its research unit, José Cato. I also thank Cláudia Conceição Luvau and architect Manuel Pimentel, the Director of the Naonal Instute for Spaal Planning and Urban Development, and architect Helder José, the Director of the Instute of Planning and Urban Management of Luanda at the me of research, for parcipang in and supporng the research process. This working paper benefited from the comments of Professor Edgar Pieterse, the principal invesgator of the PASGR research project ‘Urban governance and turning African cies around’; the expert review panel put together by PASGR, comprising Dr. -

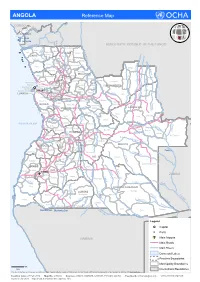

ANGOLA Reference Map

ANGOLA Reference Map CONGO L Belize ua ng Buco Zau o CABINDA Landana Lac Nieba u l Lac Vundu i Cabinda w Congo K DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO o z Maquela do Zombo o p Noqui e Kuimba C Soyo M Mbanza UÍGE Kimbele u -Kongo a n ZAIRE e Damba g g o id Tomboco br Buengas M Milunga I n Songo k a Bembe i C p Mucaba s Sanza Pombo a i a u L Nzeto c u a i L l Chitato b Uige Bungo e h o e d C m Ambuila g e Puri Massango b Negage o MALANGE L Ambriz Kangola o u Nambuangongo b a n Kambulo Kitexe C Ambaca m Marimba g a Kuilo Lukapa h u Kuango i Kalandula C Dande Bolongongo Kaungula e u Sambizanga Dembos Kiculungo Kunda- m Maianga Rangel b Cacuaco Bula-Atumba Banga Kahombo ia-Baze LUNDA NORTE e Kilamba Kiaxi o o Cazenga eng Samba d Ingombota B Ngonguembo Kiuaba n Pango- -Caju a Saurimo Barra Do Cuanza LuanCda u u Golungo-Alto -Nzoji Viana a Kela L Samba Aluquem Lukala Lul o LUANDA nz o Lubalo a Kazengo Kakuso m i Kambambe Malanje h Icolo e Bengo Mukari c a KWANZA-NORTE Xa-Muteba u Kissama Kangandala L Kapenda- L Libolo u BENGO Mussende Kamulemba e L m onga Kambundi- ando b KWANZA-SUL Lu Katembo LUNDA SUL e Kilenda Lukembo Porto Amboim C Kakolo u Amboim Kibala t Mukonda Cu a Dala Luau v t o o Ebo Kirima Konda Ca s Z ATLANTIC OCEAN Waco Kungo Andulo ai Nharea Kamanongue C a Seles hif m um b Sumbe Bailundo Mungo ag e Leua a z Kassongue Kuemba Kameia i C u HUAMBO Kunhinga Luena vo Luakano Lobito Bocoio Londuimbali Katabola Alto Zambeze Moxico Balombo Kachiungo Lun bela gue-B Catum Ekunha Chinguar Kuito Kamakupa ungo a Benguela Chinjenje z Huambo n MOXICO