Baz1a, Which Is the Closest Mammalian Homolog of Acf1 from Drosophila

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Functional Roles of Bromodomain Proteins in Cancer

cancers Review Functional Roles of Bromodomain Proteins in Cancer Samuel P. Boyson 1,2, Cong Gao 3, Kathleen Quinn 2,3, Joseph Boyd 3, Hana Paculova 3 , Seth Frietze 3,4,* and Karen C. Glass 1,2,4,* 1 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Colchester, VT 05446, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Pharmacology, Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT 05405, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Biomedical and Health Sciences, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT 05405, USA; [email protected] (C.G.); [email protected] (J.B.); [email protected] (H.P.) 4 University of Vermont Cancer Center, Burlington, VT 05405, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.F.); [email protected] (K.C.G.) Simple Summary: This review provides an in depth analysis of the role of bromodomain-containing proteins in cancer development. As readers of acetylated lysine on nucleosomal histones, bromod- omain proteins are poised to activate gene expression, and often promote cancer progression. We examined changes in gene expression patterns that are observed in bromodomain-containing proteins and associated with specific cancer types. We also mapped the protein–protein interaction network for the human bromodomain-containing proteins, discuss the cellular roles of these epigenetic regu- lators as part of nine different functional groups, and identify bromodomain-specific mechanisms in cancer development. Lastly, we summarize emerging strategies to target bromodomain proteins in cancer therapy, including those that may be essential for overcoming resistance. Overall, this review provides a timely discussion of the different mechanisms of bromodomain-containing pro- Citation: Boyson, S.P.; Gao, C.; teins in cancer, and an updated assessment of their utility as a therapeutic target for a variety of Quinn, K.; Boyd, J.; Paculova, H.; cancer subtypes. -

Functional Compensation Among HMGN Variants Modulates the Dnase I Hypersensitive Sites at Enhancers

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 9, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research Functional compensation among HMGN variants modulates the DNase I hypersensitive sites at enhancers Tao Deng,1,12 Z. Iris Zhu,2,12 Shaofei Zhang,1 Yuri Postnikov,1 Di Huang,2 Marion Horsch,3 Takashi Furusawa,1 Johannes Beckers,3,4,5 Jan Rozman,3,5 Martin Klingenspor,6,7 Oana Amarie,3,8 Jochen Graw,3,8 Birgit Rathkolb,3,5,9 Eckhard Wolf,9 Thure Adler,3 Dirk H. Busch,10 Valérie Gailus-Durner,3 Helmut Fuchs,3 Martin Hrabeˇ de Angelis,3,4,5 Arjan van der Velde,2,13 Lino Tessarollo,11 Ivan Ovcherenko,2 David Landsman,2 and Michael Bustin1 1Protein Section, Laboratory of Metabolism, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, USA; 2Computational Biology Branch, National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, USA; 3German Mouse Clinic, Institute of Experimental Genetics, Helmholtz Zentrum München, German Research Center for Environmental Health, 85764 Neuherberg, Germany; 4Experimental Genetics, Center of Life and Food Sciences Weihenstephan, Technische Universität München, 85354 Freising-Weihenstephan, Germany; 5German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD), 85764 Neuherberg, Germany; 6Molecular Nutritional Medicine, Technische Universität München, 85350 Freising, Germany; 7Center for Nutrition and Food Sciences, Technische Universität München, 85350 Freising, Germany; 8Institute of Developmental Genetics (IDG), 85764 -

Cyclin D1 Is a Direct Transcriptional Target of GATA3 in Neuroblastoma Tumor Cells

Oncogene (2010) 29, 2739–2745 & 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0950-9232/10 $32.00 www.nature.com/onc SHORT COMMUNICATION Cyclin D1 is a direct transcriptional target of GATA3 in neuroblastoma tumor cells JJ Molenaar1,2, ME Ebus1, J Koster1, E Santo1, D Geerts1, R Versteeg1 and HN Caron2 1Department of Human Genetics, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands and 2Department of Pediatric Oncology, Emma Kinderziekenhuis, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Almost all neuroblastoma tumors express excess levels of 2000). Several checkpoints normally prevent premature Cyclin D1 (CCND1) compared to normal tissues and cell-cycle progression and cell division. The crucial G1 other tumor types. Only a small percentage of these entry point is controlled by the D-type Cyclins that can neuroblastoma tumors have high-level amplification of the activate CDK4/6 that in turn phosphorylate the pRb Cyclin D1 gene. The other neuroblastoma tumors have protein. This results in a release of the E2F transcription equally high Cyclin D1 expression without amplification. factor that causes transcriptional upregulation of Silencing of Cyclin D1 expression was previously found to numerous genes involved in further progression of the trigger differentiation of neuroblastoma cells. Over- cell cycle (Sherr, 1996). expression of Cyclin D1 is therefore one of the most Neuroblastomas are embryonal tumors that originate frequent mechanisms with a postulated function in neuro- from precursor cells of the sympathetic nervous system. blastoma pathogenesis. The cause for the Cyclin D1 This tumor has a very poor prognosis and despite the overexpression is unknown. -

Gene Regulation and Speciation in House Mice

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 26, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research Gene regulation and speciation in house mice Katya L. Mack,1 Polly Campbell,2 and Michael W. Nachman1 1Museum of Vertebrate Zoology and Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-3160, USA; 2Department of Integrative Biology, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, Oklahoma 74078, USA One approach to understanding the process of speciation is to characterize the genetic architecture of post-zygotic isolation. As gene regulation requires interactions between loci, negative epistatic interactions between divergent regulatory elements might underlie hybrid incompatibilities and contribute to reproductive isolation. Here, we take advantage of a cross between house mouse subspecies, where hybrid dysfunction is largely unidirectional, to test several key predictions about regulatory divergence and reproductive isolation. Regulatory divergence between Mus musculus musculus and M. m. domesticus was charac- terized by studying allele-specific expression in fertile hybrid males using mRNA-sequencing of whole testes. We found ex- tensive regulatory divergence between M. m. musculus and M. m. domesticus, largely attributable to cis-regulatory changes. When both cis and trans changes occurred, they were observed in opposition much more often than expected under a neutral model, providing strong evidence of widespread compensatory evolution. We also found evidence for lineage-specific positive se- lection on a subset of genes related to transcriptional regulation. Comparisons of fertile and sterile hybrid males identified a set of genes that were uniquely misexpressed in sterile individuals. Lastly, we discovered a nonrandom association between these genes and genes showing evidence of compensatory evolution, consistent with the idea that regulatory interactions might contribute to Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities and be important in speciation. -

HMGB1 in Health and Disease R

Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine Journal Articles Academic Works 2014 HMGB1 in health and disease R. Kang R. C. Chen Q. H. Zhang W. Hou S. Wu See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://academicworks.medicine.hofstra.edu/articles Part of the Emergency Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Kang R, Chen R, Zhang Q, Hou W, Wu S, Fan X, Yan Z, Sun X, Wang H, Tang D, . HMGB1 in health and disease. 2014 Jan 01; 40():Article 533 [ p.]. Available from: https://academicworks.medicine.hofstra.edu/articles/533. Free full text article. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine Academic Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine Academic Works. Authors R. Kang, R. C. Chen, Q. H. Zhang, W. Hou, S. Wu, X. G. Fan, Z. W. Yan, X. F. Sun, H. C. Wang, D. L. Tang, and +8 additional authors This article is available at Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine Academic Works: https://academicworks.medicine.hofstra.edu/articles/533 NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Mol Aspects Med. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 December 01. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Mol Aspects Med. 2014 December ; 0: 1–116. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2014.05.001. HMGB1 in Health and Disease Rui Kang1,*, Ruochan Chen1, Qiuhong Zhang1, Wen Hou1, Sha Wu1, Lizhi Cao2, Jin Huang3, Yan Yu2, Xue-gong Fan4, Zhengwen Yan1,5, Xiaofang Sun6, Haichao Wang7, Qingde Wang1, Allan Tsung1, Timothy R. -

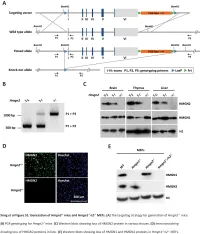

Loss of ISWI Atpase SMARCA5 (SNF2H) in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells Inhibits Proliferation and Chromatid Cohesion

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Loss of ISWI ATPase SMARCA5 (SNF2H) in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells Inhibits Proliferation and Chromatid Cohesion 1, 1, 1 2,3,4 1 Tomas Zikmund y , Helena Paszekova y , Juraj Kokavec , Paul Kerbs , Shefali Thakur , Tereza Turkova 1, Petra Tauchmanova 1, Philipp A. Greif 2,3,4 and Tomas Stopka 1,* 1 Biocev, 1st Medical Faculty, Charles University, 25250 Vestec, Czech Republic; [email protected] (T.Z.); [email protected] (H.P.); [email protected] (J.K.); [email protected] (S.T.); [email protected] (T.T.); [email protected] (P.T.) 2 Department of Medicine III, University Hospital, LMU Munich, D-80539 Munich, Germany; [email protected] (P.K.); [email protected] (P.A.G.) 3 German Cancer Consortium (DKTK), partner site Munich, D-80336 Munich, Germany 4 German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-32587-3001 These authors contributed equally. y Received: 26 February 2020; Accepted: 16 March 2020; Published: 18 March 2020 Abstract: ISWI chromatin remodeling ATPase SMARCA5 (SNF2H) is a well-known factor for its role in regulation of DNA access via nucleosome sliding and assembly. SMARCA5 transcriptionally inhibits the myeloid master regulator PU.1. Upregulation of SMARCA5 was previously observed in CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients. Since high levels of SMARCA5 are necessary for intensive cell proliferation and cell cycle progression of developing hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in mice, we reasoned that removal of SMARCA5 enzymatic activity could affect the cycling or undifferentiated state of leukemic progenitor-like clones. -

Insights Into Regulation of Human RAD51 Nucleoprotein Filament Activity During

Insights into Regulation of Human RAD51 Nucleoprotein Filament Activity During Homologous Recombination Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ravindra Bandara Amunugama, B.S. Biophysics Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Richard Fishel PhD, Advisor Jeffrey Parvin MD PhD Charles Bell PhD Michael Poirier PhD Copyright by Ravindra Bandara Amunugama 2011 ABSTRACT Homologous recombination (HR) is a mechanistically conserved pathway that occurs during meiosis and following the formation of DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) induced by exogenous stresses such as ionization radiation. HR is also involved in restoring replication when replication forks have stalled or collapsed. Defective recombination machinery leads to chromosomal instability and predisposition to tumorigenesis. However, unregulated HR repair system also leads to similar outcomes. Fortunately, eukaryotes have evolved elegant HR repair machinery with multiple mediators and regulatory inputs that largely ensures an appropriate outcome. A fundamental step in HR is the homology search and strand exchange catalyzed by the RAD51 recombinase. This process requires the formation of a nucleoprotein filament (NPF) on single-strand DNA (ssDNA). In Chapter 2 of this dissertation I describe work on identification of two residues of human RAD51 (HsRAD51) subunit interface, F129 in the Walker A box and H294 of the L2 ssDNA binding region that are essential residues for salt-induced recombinase activity. Mutation of F129 or H294 leads to loss or reduced DNA induced ATPase activity and formation of a non-functional NPF that eliminates recombinase activity. DNA binding studies indicate that these residues may be essential for sensing the ATP nucleotide for a functional NPF formation. -

The Function and Evolution of C2H2 Zinc Finger Proteins and Transposons

The function and evolution of C2H2 zinc finger proteins and transposons by Laura Francesca Campitelli A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Molecular Genetics University of Toronto © Copyright by Laura Francesca Campitelli 2020 The function and evolution of C2H2 zinc finger proteins and transposons Laura Francesca Campitelli Doctor of Philosophy Department of Molecular Genetics University of Toronto 2020 Abstract Transcription factors (TFs) confer specificity to transcriptional regulation by binding specific DNA sequences and ultimately affecting the ability of RNA polymerase to transcribe a locus. The C2H2 zinc finger proteins (C2H2 ZFPs) are a TF class with the unique ability to diversify their DNA-binding specificities in a short evolutionary time. C2H2 ZFPs comprise the largest class of TFs in Mammalian genomes, including nearly half of all Human TFs (747/1,639). Positive selection on the DNA-binding specificities of C2H2 ZFPs is explained by an evolutionary arms race with endogenous retroelements (EREs; copy-and-paste transposable elements), where the C2H2 ZFPs containing a KRAB repressor domain (KZFPs; 344/747 Human C2H2 ZFPs) are thought to diversify to bind new EREs and repress deleterious transposition events. However, evidence of the gain and loss of KZFP binding sites on the ERE sequence is sparse due to poor resolution of ERE sequence evolution, despite the recent publication of binding preferences for 242/344 Human KZFPs. The goal of my doctoral work has been to characterize the Human C2H2 ZFPs, with specific interest in their evolutionary history, functional diversity, and coevolution with LINE EREs. -

Supplemental Data.Pdf

Table S1. Summary of sequencing results A. DNase‐seq data % Align % Mismatch % >=Q30 bases Sample ID # Reads % unique reads (PF) Rate (PF) (PF) WT_1 84,301,522 86.76 0.52 93.34 96.30 WT_2 98,744,222 84.97 0.51 93.75 89.94 Hmgn1‐/‐_1 79,620,656 83.94 0.86 90.58 88.65 Hmgn1‐/‐_2 62,673,782 84.13 0.87 91.30 89.18 Hmgn2‐/‐_1 87,734,440 83.49 0.71 91.81 90.00 Hmgn2‐/‐_2 82,498,808 83.25 0.69 92.73 90.66 Hmgn1‐/‐n2‐/‐_1 71,739,638 68.51 2.31 81.11 89.22 Hmgn1‐/‐n2‐/‐_2 74,113,682 68.19 2.37 81.16 86.57 B. ChIP‐seq data Histone % Align % Mismatch % >=Q30 % unique Genotypes # Reads marks (PF) Rate (PF) bases (PF) reads H3K4me1 100670054 92.99 0.28 91.21 87.29 H3K4me3 67064272 91.97 0.35 89.11 27.15 WT H3K27ac 90,340,242 93.57 0.28 95.02 89.80 input 111,292,572 78.24 0.55 96.07 86.99 H3K4me1 84598176 92.34 0.33 91.2 81.69 H3K4me3 90032064 92.19 0.44 88.76 15.81 Hmgn1‐/‐n2‐/‐ H3K27ac 86,260,526 93.40 0.29 94.94 87.49 input 78,142,334 78.47 0.56 95.82 81.11 C. MNase‐seq data % Mismatch % >=Q30 bases % unique Sample ID # Reads % Align (PF) Rate (PF) (PF) reads WT_1_Extensive 45,232,694 55.23 1.49 90.22 81.73 WT_1_Limited 105,460,950 58.03 1.39 90.81 79.62 WT_2_Extensive 40,785,338 67.34 1.06 89.76 89.60 WT_2_Limited 105,738,078 68.34 1.05 90.29 85.96 Hmgn1‐/‐n2‐/‐_1_Extensive 117,927,050 55.74 1.49 89.50 78.01 Hmgn1‐/‐n2‐/‐_1_Limited 61,846,742 63.76 1.22 90.57 84.55 Hmgn1‐/‐n2‐/‐_2_Extensive 137,673,830 60.04 1.30 89.28 78.99 Hmgn1‐/‐n2‐/‐_2_Limited 45,696,614 62.70 1.21 90.71 85.52 D. -

Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis Reveals Molecular Subtypes of Pancreatic Cancer

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, 2017, Vol. 8, (No. 17), pp: 28990-29012 Research Paper Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis reveals molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer Nitish Kumar Mishra1 and Chittibabu Guda1,2,3,4 1Department of Genetics, Cell Biology and Anatomy, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, 68198, USA 2Bioinformatics and Systems Biology Core, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, 68198, USA 3Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, 68198, USA 4Fred and Pamela Buffet Cancer Center, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, 68198, USA Correspondence to: Chittibabu Guda, email: [email protected] Keywords: TCGA, pancreatic cancer, differential methylation, integrative analysis, molecular subtypes Received: October 20, 2016 Accepted: February 12, 2017 Published: March 07, 2017 Copyright: Mishra et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT Pancreatic cancer (PC) is the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States with a five-year patient survival rate of only 6%. Early detection and treatment of this disease is hampered due to lack of reliable diagnostic and prognostic markers. Recent studies have shown that dynamic changes in the global DNA methylation and gene expression patterns play key roles in the PC development; hence, provide valuable insights for better understanding the initiation and progression of PC. In the current study, we used DNA methylation, gene expression, copy number, mutational and clinical data from pancreatic patients. -

Pathway and Network Analysis of Somatic Mutations Across Cancer

Network Analysis of Mutaons Across Cancer Types Ben Raphael Fabio Vandin, Max Leiserson, Hsin-Ta Wu Department of Computer Science Center for Computaonal Molecular Biology Significantly Mutated Genes Muta#on Matrix Stascal test Genes Paents Frequency Number Paents Study Num. Samples Num. SMG TCGA Ovarian (2011) 316 10 TCGA Breast (2012) 510 35 TCGA Colorectal (2012) 276 32 background mutaon rate (BMR), gene specific effects, etc. Significantly Mutated Genes à Pathways Stascal test Frequency Number Paents TCGA Colorectal (Nature 2012) TCGA Ovarian (Nature 2011) background mutaon rate (BMR), gene specific effects, etc. Advantages of Large Datasets Prior knowledge of groups of genes Genes Paents Known pathways Interac3on Network None Prior knowledge • Novel pathways or interac3ons between pathways (crosstalk) • Topology of interac3ons Two Algorithms Prior knowledge of groups of genes Genes Paents Known pathways Interac3on Network None Prior knowledge Number of Hypotheses HotNet subnetworks of Dendrix interac3on network Exclusive gene sets HotNet: Problem Defini3on Given: 1. Network G = (V, E) V = genes. E = interac3ons b/w genes 2. Binary mutaon matrix Genes = mutated = not mutated Paents Find: Connected subnetworks mutated in a significant number of paents. Subnetwork Properes Mutaon frequency/score AND network topology Frequency Number Paents • Moderate frequency/score • High frequency/score • Highly connected • Connected through high-degree node. Example: TP53 has 238 neighbors in HPRD network Mutated subnetworks: HotNet* Muta#on Matrix Human Interac#on Network Genes = mutated genes Paents (1) Muta#on à heat diffusion Extract “significantly hot” subnetworks Hot (2) Cold *F. Vandin, E. Upfal, and B. J. Raphael. J. Comp.Biol. (2011). Also RECOMB (2010). Stas3cal Test Muta#on Matrix Random Binary Matrix Genes Genes Paents Paents Xs = number of subnetworks ≥ s genes Two-stage mul-hypothesis test: Rigorously bound FDR. -

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Table 1. 492 genes are unique to 0 h post-heat timepoint. The name, p-value, fold change, location and family of each gene are indicated. Genes were filtered for an absolute value log2 ration 1.5 and a significance value of p ≤ 0.05. Symbol p-value Log Gene Name Location Family Ratio ABCA13 1.87E-02 3.292 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family unknown transporter A (ABC1), member 13 ABCB1 1.93E-02 −1.819 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family Plasma transporter B (MDR/TAP), member 1 Membrane ABCC3 2.83E-02 2.016 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family Plasma transporter C (CFTR/MRP), member 3 Membrane ABHD6 7.79E-03 −2.717 abhydrolase domain containing 6 Cytoplasm enzyme ACAT1 4.10E-02 3.009 acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 1 Cytoplasm enzyme ACBD4 2.66E-03 1.722 acyl-CoA binding domain unknown other containing 4 ACSL5 1.86E-02 −2.876 acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain Cytoplasm enzyme family member 5 ADAM23 3.33E-02 −3.008 ADAM metallopeptidase domain Plasma peptidase 23 Membrane ADAM29 5.58E-03 3.463 ADAM metallopeptidase domain Plasma peptidase 29 Membrane ADAMTS17 2.67E-04 3.051 ADAM metallopeptidase with Extracellular other thrombospondin type 1 motif, 17 Space ADCYAP1R1 1.20E-02 1.848 adenylate cyclase activating Plasma G-protein polypeptide 1 (pituitary) receptor Membrane coupled type I receptor ADH6 (includes 4.02E-02 −1.845 alcohol dehydrogenase 6 (class Cytoplasm enzyme EG:130) V) AHSA2 1.54E-04 −1.6 AHA1, activator of heat shock unknown other 90kDa protein ATPase homolog 2 (yeast) AK5 3.32E-02 1.658 adenylate kinase 5 Cytoplasm kinase AK7