Wilayah Mindanao’ by Joseph Franco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

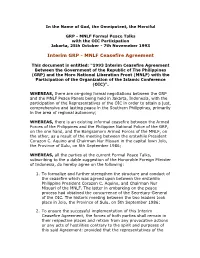

Interim GRP - MNLF Ceasefire Agreement

In the Name of God, the Omnipotent, the Merciful GRP - MNLF Formal Peace Talks with the OIC Participation Jakarta, 25th October - 7th Novemeber 1993 Interim GRP - MNLF Ceasefire Agreement This document is entitled: "1993 Interim Ceasefire Agreement Between the Government of the Republic of The Philippines (GRP) and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) with the Participation of the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC)". WHEREAS, there are on-going formal negotiations between the GRP and the MNLF Peace Panels being held in Jakarta, Indonesia, with the participation of the Representatives of the OIC in order to attain a just, comprehensive and lasting peace in the Southern Philippines, primarily in the area of regional autonomy; WHEREAS, there is an existing informal ceasefire between the Armed Forces of the Philippines and the Philippine National Police of the GRP, on the one hand, and the Bangsamoro Armed Forces of the MNLF, on the other, as a result of the meeting between the erstwhile President Corazon C. Aquino and Chairman Nur Misuari in the capital lown Jolo, the Province of Sulu, on 5th September 1986; WHEREAS, all the parties at the current Formal Peace Talks, subscribing to the a dable suggestion of the Honorable Foreign Minister of Indonesia, do hereby agree on the following: 1. To formalize and further strengthen the structure and conduct of the ceasefire which was agreed upon between the erstwhile Philippine President Corazon C. Aquino, and Chairman Nur Misuari of the MNLF. The latter in embarking on the peace process had obtained the concurrence of the Secretary-General of the OIC. -

KEPUTUSAN MAHKAMAH TERHADAP AL-MA'unah ADALAH PROSES KEADILAN, KATA PM (Bernama 29/12/2001)

29 DEC 2001 Mahathir-Ma'unah KEPUTUSAN MAHKAMAH TERHADAP AL-MA'UNAH ADALAH PROSES KEADILAN, KATA PM KUALA LUMPUR, 29 Dis (Bernama) -- Perdana Menteri Datuk Seri Dr Mahathir Mohamad berkata kerajaan tidak pernah bertolak ansur terhadap tindakan ganas seperti yang dilakukan kumpulan Al-Ma'unah dan rakyat haruslah sedar akan akibat undang-undang yang menanti mereka yang melakukannya. Semasa diminta mengulas hukuman mati dan penjara sepanjang hayat yang dikenakan terhadap 19 anggota Al-Ma'unah kerana melancarkan peperangan terhadap Yang di-Pertuan Agong, beliau berkata: "Kerajaan tidak pernah bertolak ansur terhadap tindakan sedemikian. Rakyat patut tahu." Dr Mahathir, yang juga pengerusi Barisan Nasional (BN) dan presiden Umno berkata demikian pada satu sidang akhbar selepas merasmikan perhimpunan agung Parti Progresif Penduduk Malaysia ke-48 di Pusat Dagangan Dunia Putra (PWTC) di sini. Semasa ditanya sama ada beliau gembira dengan hukuman itu, Perdana Menteri berkata ia bukan soal suka atau gembira. "Saya tidak kata yang saya gembira. Saya tidak gembira apabila seseorang itu dihukum mati. Ini merupakan satu keputusan. Ia bukan soal kegembiraan atau suka hati atau apa-apapun. Ia merupakan soal mendukung keadilan," katanya. Mereka yang dihukum mati ialah ketua kumpulan Al-Ma'unah Mohamed Amin Mohamed Razali, orang kanannya Zahit Muslim dan ketua wilayah utara kumpulan itu Jamaluddin Darus. Kesalahan itu dilakukan di tiga tempat di Perak -- dua di Gerik, Hulu Perak dan ketiga Bukit Jenalek, Sauk di Kuala Kangsar. Detektif Korporal R. Saghadevan dan Truper Matthew Medan telah ditembak di Bukit Jenalek. Dr Mahathir berkata: "Saya fikir keluarga orang yang telah dibunuh itu tentulah berasa di negara kita ini terdapat keadilan tidak kira kaum atau agama. -

Counter Terrorist Trends and Analysis Volume 6, Issue 1 Jan/Feb 2014

Counter Terrorist Trends and Analysis Volume 6, Issue 1 Jan/Feb 2014 Annual Threat Assessment SOUTHEAST ASIA Myanmar, Thailand, Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia and Singapore SOUTH ASIA Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka EAST AND CENTRAL ASIA China and Central Asia MIDDLE EAST AND AFRICA Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Egypt, Libya and Somalia INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND TERRORISM RESEARCH S. RAJARATNAM SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES NANYANG TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY 2 ANNUAL THREAT ASSESSMENT Terrorism and Political Violence in 2013 Southeast Asia peace talks were held in January 2014. Iraq, too, remains besieged by sectarian violence and constant attacks. In Yemen, Southeast Asia has seen some of its insurgencies and conflicts multiple insurgencies and a robust threat from Al Qaeda in the diminish while others have continued unabated. In Thailand, the Arabian Peninsula have hampered an already difficult political restive south continued to see violence in 2013 while Bangkok transition. In Egypt, Morsi’s ouster has seen protests continuing witnessed a political crisis with protests against the government to plague the country while the military attempts another turning violent. In Myanmar, reforms have moved forward but political transition. Libya, meanwhile, faces a persistent security communal violence continues to plague the country and has challenge in its southern border region and the success of its evolved from targeting Rohingyas towards Muslim minority transition after Gaddafi will depend on the militias which communities in general. Indonesia continues to face a potent deposed the former dictator giving up their arms. In Somalia, threat from radicalization and concern has emerged over the al-Shabaab has intensified its campaign against the role its “hard” counterterrorist approach is playing in fueling government in the wake of a hardline faction emerging further extremism. -

Prof. M. Kamal Hassan Rector, International Islamic University (IIUM), Malaysia

“ISLAM IN SOUTHEAST ASIA TODAY”∗ Prof. M. Kamal Hassan Rector, International Islamic University (IIUM), Malaysia Southeast Asia may be divided into two parts; a) the Muslim majority countries of Indonesia (230 million), Malaysia (23 million) and Brunei Darussalam (360,000), and b) the Muslim minority countries of Thailand, the Philippines, Cambodia, Singapore, Myanmar, Vietnam and Laos in a multi-religious region in which Hinduism, Buddhism and animism had been the dominant religions or belief systems of the populace prior to the advent of Islam. Muslim communities of this region have lived for centuries with neighbours consisting of Catholics, Protestants, Confucianists, Taoists, Buddhists, Hindus, Sikhs, animists and ancestor worshippers. This multi-religious, multi-cultural and multi-ethnic background is an important factor in conditioning the religio-political thought and behaviour of the Muslims in different nation states of Southeast Asia. The different political systems and the way each state treats Islam and Muslims constitute another factor which determines the differing responses of Muslims as a religio-political force. It can be said that the Muslim community in the Malay-Indonesian world has gone through six major periods in the long process of Islamization: 1. The period of initial conversion to Islam signifying a radical change in belief system from polytheism to Islamic monotheism. ∗ Paper presented at the Conference on Eastern-Western Dialogue, organized by Casa Asia in Madrid, Spain on 29th October 2003 and in Casa Asia, Barcelona, on 30th October 2003. 2 2. The period of living in independent Muslim sultanates which combined Islamic beliefs and practices with pre-Islamic Malay customs (adat) and values, thus allowing for a degree of syncreticism and ecclecticism at the level of folk religion in several areas. -

The Lahad Datu Incursion and Its Impact on Malaysia's Security

THE LAHAD DATU INCURSION its Impact on MALAYSIA’S SECURITY by JASMINE JAWHAR & KENNIMROD SARIBURAJA “Coming together is a beginning. Keeping together is progress. Working together is success.” - Henry Ford - Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Cataloguing-in Publication Data Jasmine Jawhar THE LAHAD DATU INCURSION AND ITS IMPACT ON MALAYSIA’S SECURITY ISBN: 978-983-44397-8-1 1. National security--Malaysia 2. Territorial waters--Sabah (Malaysia(. 3. Internal security-- Malaysia-- Lahad Datu (Sabah). 4. Security clearances-- Malaysia -- Lahad Datu (Sabah). 5. Lahad Datu (Sabah, Malaysia)-- emigration and immigration. I. Sariburaja, Kennimrod, 1983-.II. Title. 959.52152 First published in 2016 SEARCCT is dedicated to advocating the understanding of issues pertaining to terrorism and counter-terrorism and contributing ideas for counter- terrorism policy. The Centre accomplishes this mainly by organising capacity building courses, research, publications and public awareness programmes. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. All statements of facts, opinions and expressions contained in this work are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Malaysia. The Government of Malaysia assume no responsibility for any statements of facts or opinions expressed in this work. PUBLISHER The Southeast Asia Regional Centre for Counter-Terrorism (SEARCCT), Ministry -

Pacnet Number 7 Jan

Pacific Forum CSIS Honolulu, Hawaii PacNet Number 7 Jan. 19, 2016 Islamic State branches in Southeast Asia by Rohan Ma’rakah Al-Ansar Battalion led by Abu Ammar; 3) Ansarul Gunaratna Khilafah Battalion led by Abu Sharifah; and 4) Al Harakatul Islamiyyah Battalion in Basilan led by Isnilon Hapilon, who is Rohan Gunaratna ([email protected]) is Professor of the overall leader of the four battalions. Al Harakatul Security Studies at the S. Rajaratnam School of Security Islamiyyah is the original name of ASG. Referring to Hapilon Studies (RSIS) and head of the International Centre for as “Sheikh Mujahid Abu Abdullah Al-Filipini,” an IS official Political Violence and Terrorism Research (ICPVTR) at RSIS, organ Al-Naba’ reported on the unification of the “battalions” Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Earlier of God’s fighters (“mujahidin”). The IS choice of Hapilon to versions of this article appeared in The Straits Times and as lead an IS province in the Philippines presents a long-term RSIS Commentary 004/2016. threat to the Philippines and beyond. The so-called Islamic State (IS) is likely to create IS At the oath-taking to Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, the battalions branches in the Philippines and Indonesia in 2016. Although were represented by Ansar Al-Shariah Battalion leader Abu the Indonesian military pre-empted IS plans to declare a Anas Al-Muhajir who goes by the alias Abraham. Abu Anas satellite state of the “caliphate” in eastern Indonesia, IS is Al-Muhajir is Mohammad bin Najib bin Hussein from determined to declare such an entity in at least one part of Malaysia and his battalion is in charge of laws and other Southeast Asia. -

Counter-Insurgency Vs. Counter-Terrorism in Mindanao

THE PHILIPPINES: COUNTER-INSURGENCY VS. COUNTER-TERRORISM IN MINDANAO Asia Report N°152 – 14 May 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. ISLANDS, FACTIONS AND ALLIANCES ................................................................ 3 III. AHJAG: A MECHANISM THAT WORKED .......................................................... 10 IV. BALIKATAN AND OPLAN ULTIMATUM............................................................. 12 A. EARLY SUCCESSES..............................................................................................................12 B. BREAKDOWN ......................................................................................................................14 C. THE APRIL WAR .................................................................................................................15 V. COLLUSION AND COOPERATION ....................................................................... 16 A. THE AL-BARKA INCIDENT: JUNE 2007................................................................................17 B. THE IPIL INCIDENT: FEBRUARY 2008 ..................................................................................18 C. THE MANY DEATHS OF DULMATIN......................................................................................18 D. THE GEOGRAPHICAL REACH OF TERRORISM IN MINDANAO ................................................19 -

Policy Notes March 2021

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY MARCH 2021 POLICY NOTES NO. 100 In the Service of Ideology: Iran’s Religious and Socioeconomic Activities in Syria Oula A. Alrifai “Syria is the 35th province and a strategic province for Iran...If the enemy attacks and aims to capture both Syria and Khuzestan our priority would be Syria. Because if we hold on to Syria, we would be able to retake Khuzestan; yet if Syria were lost, we would not be able to keep even Tehran.” — Mehdi Taeb, commander, Basij Resistance Force, 2013* Taeb, 2013 ran’s policy toward Syria is aimed at providing strategic depth for the Pictured are the Sayyeda Tehran regime. Since its inception in 1979, the regime has coopted local Zainab shrine in Damascus, Syrian Shia religious infrastructure while also building its own. Through youth scouts, and a pro-Iran I proxy actors from Lebanon and Iraq based mainly around the shrine of gathering, at which the banner Sayyeda Zainab on the outskirts of Damascus, the Iranian regime has reads, “Sayyed Commander Khamenei: You are the leader of the Arab world.” *Quoted in Ashfon Ostovar, Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (2016). Khuzestan, in southwestern Iran, is the site of a decades-long separatist movement. OULA A. ALRIFAI IRAN’S RELIGIOUS AND SOCIOECONOMIC ACTIVITIES IN SYRIA consolidated control over levers in various localities. against fellow Baathists in Damascus on November Beyond religious proselytization, these networks 13, 1970. At the time, Iran’s Shia clerics were in exile have provided education, healthcare, and social as Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi was still in control services, among other things. -

'Battle of Marawi': Death and Destruction in the Philippines

‘THE BATTLE OF MARAWI’ DEATH AND DESTRUCTION IN THE PHILIPPINES Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Military trucks drive past destroyed buildings and a mosque in what was the main battle (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. area in Marawi, 25 October 2017, days after the government declared fighting over. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © Ted Aljibe/AFP/Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 35/7427/2017 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP 4 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. METHODOLOGY 10 3. BACKGROUND 11 4. UNLAWFUL KILLINGS BY MILITANTS 13 5. HOSTAGE-TAKING BY MILITANTS 16 6. ILL-TREATMENT BY GOVERNMENT FORCES 18 7. ‘TRAPPED’ CIVILIANS 21 8. LOOTING BY ALL PARTIES TO THE CONFLICT 23 9. -

Judging in God's Name

Judging in God’s Name 153 Oxford Journal of Law and Religion , Vol. 3, No. 1 (2014), pp. 152–167 doi:10.1093/ojlr/rwt035 religious state, at least for the 60% of Malaysian Muslims who are subject to Published Advance Access August 14, 2013 such rules and regulations. 4 Likewise, if secularism is understood as the strict separation of religion from governance, Malaysia appears to be the antithesis of Judging in God’s Name: State Power, a secular state. Few would disagree that aspects of religion and governance are intertwined Secularism, and the Politics of Islamic law in contemporary Malaysia, but the simple secular-versus-religious dichotomy tends to obfuscate the ways that religious law is transformed as a result of in Malaysia incorporation as state law. The imposition of select fragments of fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) should not be understood as the implementation of an ‘Islamic’ system of governance, or the achievement of an ‘Islamic state’, for no such TAMIR MOUSTAFA* ideal-type exists.5 Instead, Malaysia provides a textbook example of how core principles in usul al-fiqh (Islamic legal theory) are subverted as a result of state Malaysia ranks sixth out of 175 countries worldwide in the degree of state appropriation. 6 Malaysia thus provides an important opportunity to rethink the regulation of religion. The Malaysian state enforces myriad rules and regulations in relationship between the state, secularism, and the politics of Islamic law. the name of Islam and claims a monopoly on the interpretation of Islamic law. This study proceeds in three parts. First, I provide the reader with a brief However, this should not be understood as the implementation of an ‘Islamic’ system of governance or the realization of an ‘Islamic state’. -

Philippines: Factors of Century-Old Conϐlict and Current Violent Extremism in the South

Issue 22, January 2018 Philippines: Factors of Century-Old Conϐlict and Current Violent Extremism in the South Primitivo Cabanes RAGANDANG III Abstract. The perpetual struggle for separatism among Moros in Mindanao is produced on a back- ground of historical and cultural injustices and by the presence of Moro liberation fronts, along with the government responses to this issue. This article endeavors to trace and interweave the roots of historical and cultural factors of Muslim separatism in Mindanao, along with its implication to the present Marawi crisis as fueled by the ISIS-linked groups who attacked the Philippines’ Islamic city on May 23, 2017. It looks into the history of the arrival of Islam and the subsequent islamization of Mindanao. It then discusses the Muslim resistance movement against two foreign regimes, Spanish and American, which is followed by its resistance against the Philippine government. Factors that trigger Muslims’ desire for separatism include at least three notorious massacres: Jabidah, Manili, and the Tacub Massacre. Such historical factors of injustices have fuelled the century-old struggle for separatism and self-determination. With the government’s and non-government forces’ failure to pacify the island, such struggle resulted into continuing war in the region killing over 120,000 Mindanaoans. Recently, this conlict in the region was reignited when an ISIS-linked group attacked the Philippines’ Islamic city of Marawi, affecting over 84,000 internally displaced persons from over 18,000 families who are now seeking refuge in 70 different evacuation centers, in a state of discomfort, missing home and psychologically distress. Keywords: Marawi, Mindanao, Muslim, Philippines, separatism, violent extremism. -

Will Decentralization Work for the People and the Forests of Indonesia?

CHAPTER 7 CLOSER TO PEOPLE AND TREES: WILL DECENTRALIZATION WORK FOR THE PEOPLE AND THE FORESTS OF INDONESIA? Ida Aju Pradnja Resosudarmo Australian National University [email protected] or [email protected] Forthcoming in a special issue of the European Journal of Development Research Volume 16, Number 1, Spring 2004 Guest Editors: Jesse C. Ribot and Anne M. Larson Acknowledgments First prepared for the World Resources Institute Workshop on Decentralization and the Environment, Bellagio, Italy, 18-22 Feb, 2002. I am grateful to Anne Larson and Jesse Ribot for their extensive and detailed comments at various stages of the writing of this article. Comments from an anonymous reviewer were very helpful. Summary For over 30 years, Indonesia’s central government controlled its forests, the third largest area of tropical forests in the world. Driven by serious political, administrative, and economic demands for reforms, the central government has begun to decentralize, transferring new powers to the district and municipal levels. Decentralization in the forestry sector has included transferring income from permits, logging and reforestation fees, as well as the right for these lower levels of government to issue logging permits. This sudden, new access to Indonesia’s lucrative timber market has led local peoples and governments to rush to take advantage of a resource to which they previously had little right. The result has included the proliferation of permits with little regard for the effect on forest resources. Large areas, including some protected areas, are being destroyed and threatened with conversion to other uses. Local peoples, however, appear not to have been the ones receiving the primary benefits; they have been taken instead by those who have the required capital for permits and logging.