Identification of Kelp Gull Frederic Jiguet, Alvaro Jaramillo and Ian Sinclair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Official Gazette of RM", No. 28/04 and 37/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro, at Its Meeting Held on ______2007, Enacted This

In accordance with Article 6 paragraph 3 of the FT Law ("Official Gazette of RM", No. 28/04 and 37/07), the Government of the Republic of Montenegro, at its meeting held on ____________ 2007, enacted this DECISION ON CONTROL LIST FOR EXPORT, IMPORT AND TRANSIT OF GOODS Article 1 The goods that are being exported, imported and goods in transit procedure, shall be classified into the forms of export, import and transit, specifically: free export, import and transit and export, import and transit based on a license. The goods referred to in paragraph 1 of this Article were identified in the Control List for Export, Import and Transit of Goods that has been printed together with this Decision and constitutes an integral part hereof (Exhibit 1). Article 2 In the Control List, the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license, were designated by the abbreviation: “D”, and automatic license were designated by abbreviation “AD”. The goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license designated by the abbreviation “D” and specific number, license is issued by following state authorities: - D1: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for protection of human health - D2: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for animal and plant health protection, if goods are imported, exported or in transit for veterinary or phyto-sanitary purposes - D3: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for environment protection - D4: the goods for which export, import and transit is based on a license issued by the state authority competent for culture. -

The Herring Gull Complex (Larus Argentatus - Fuscus - Cachinnans) As a Model Group for Recent Holarctic Vertebrate Radiations

The Herring Gull Complex (Larus argentatus - fuscus - cachinnans) as a Model Group for Recent Holarctic Vertebrate Radiations Dorit Liebers-Helbig, Viviane Sternkopf, Andreas J. Helbig{, and Peter de Knijff Abstract Under what circumstances speciation in sexually reproducing animals can occur without geographical disjunction is still controversial. According to the ring species model, a reproductive barrier may arise through “isolation-by-distance” when peripheral populations of a species meet after expanding around some uninhabitable barrier. The classical example for this kind of speciation is the herring gull (Larus argentatus) complex with a circumpolar distribution in the northern hemisphere. An analysis of mitochondrial DNA variation among 21 gull taxa indicated that members of this complex differentiated largely in allopatry following multiple vicariance and long-distance colonization events, not primarily through “isolation-by-distance”. In a recent approach, we applied nuclear intron sequences and AFLP markers to be compared with the mitochondrial phylogeography. These markers served to reconstruct the overall phylogeny of the genus Larus and to test for the apparent biphyletic origin of two species (argentatus, hyperboreus) as well as the unex- pected position of L. marinus within this complex. All three taxa are members of the herring gull radiation but experienced, to a different degree, extensive mitochon- drial introgression through hybridization. The discrepancies between the mitochon- drial gene tree and the taxon phylogeny based on nuclear markers are illustrated. 1 Introduction Ernst Mayr (1942), based on earlier ideas of Stegmann (1934) and Geyr (1938), proposed that reproductive isolation may evolve in a single species through D. Liebers-Helbig (*) and V. Sternkopf Deutsches Meeresmuseum, Katharinenberg 14-20, 18439 Stralsund, Germany e-mail: [email protected] P. -

Long-Eared Owl Asio Otus Breeding in a Caspian Gull Larus Cachinnans

ORNIS SVECICA 30: 73–78, 2020 | DOI: 10.34080/OS.V30.22033 SHORT COMMUNICATION Received 31 August 2020 | Revised 12 November 2020 | Accepted 24 November 2020 | Published 31 December 2020 Editor: Jonas Hentati-Sundberg Long-eared Owl Asio otus breeding in a Caspian Gull Larus cachinnans colony: Reversed roles in protective nesting association? Hornugglor Asio otus häckande i en koloni med kaspiska trutar Larus cachinnans: Omvända skyddsroller för samhäckare? Klaudia Litwiniak & Marcin Przymencki . Poleska 37/17, 51-354 Wrocław, Poland | [email protected] & [email protected] WE DESCRIBE the event of Long-eared Owls Asio otus nesting on an island within a colony of Caspian Gulls Larus cachinnans at the Mietków Reservoir (SW Poland). The owls nested in an old (possible corvid) nest in a willow and raised two owlets. They probably did not hunt gulls, neither adults nor chicks. We suggest that, in this case, the Long-eared Owls benefitted from breeding within a gull colony because of the added security against predators that the gulls provided. Keywords: breeding association | breeding ecology | gull defense | nesting habitat | predator-free area Introduction The choice of a suitable habitat is presumably the damental needs of breeding adults and young, including result of integration of different habitat patches satisfy- the protection from predators and weather, and also ing the different requirements of individuals (Orians & the proximity to food sources. Because a choice may Wittenberger 1991). Bird nest-sites must meet the fun- enhance reproductive success, the behaviour involved Citation: Litwiniak K & Przymencki M. 2020. Long-eared Owl Asio otus breeding in a Caspian Gull Larus cachinnans colony: Reversed roles in protective nesting association? Ornis Svecica 30: 73–78. -

First Confirmed Record of Belcher's Gull Larus Belcheri for Colombia with Notes on the Status of Other Gull Species

First confirmed record of Belcher's Gull Larus belcheri for Colombia with notes on the status of other gull species Primer registro confirmado de la Gaviota Peruana Larus belcheri para Colombia con notas sobre el estado de otras especies de gaviotas Trevor Ellery1 & José Ferney Salgado2 1 Independent. Email: [email protected] 2 Corporación para el Fomento del Aviturismo en Colombia. Abstract We present photographic records of a Belcher's Gull Larus belcheri from the Colombian Caribbean region. These are the first confirmed records of this species in the country. Keywords: new record, range extension, gull, identification. Resumen Presentamos registros fotograficos de un individuo de la Gaviota Peruana Larus belcheri en la region del Caribe de Colombia. Estos son los primeros registros confirmados para el país. Palabras clave: Nuevo registro, extensión de distribución, gaviota, identificación. Introduction the Pacific Ocean coasts of southern South America, and Belcher's Gull or Band-tailed Gull Larus belcheri has long Olrog's Gull L. atlanticus of southern Brazil, Uruguay and been considered a possible or probable species for Argentina (Howell & Dunn 2007, Remsen et al. 2018). Colombia, with observations nearby from Panama (Hilty & Brown 1986). It was first listed for Colombia by Salaman A good rule of thumb for gulls in Colombia is that if it's not et al. (2001) without any justification or notes, perhaps on a Laughing Gull Leucophaeus atricilla, then it's interesting. the presumption that the species could never logically have A second good rule of thumb for Colombian gulls is that if reached the Panamanian observation locality from its it's not a Laughing Gull, you are probably watching it at Los southern breeding grounds without passing through the Camarones or Santuario de Fauna y Flora Los Flamencos, country. -

• Checklist of the Birds of Goa • Baltic Gull Indian BIRDS Indian BIRDS Vol

VOL. 14 NO. 1 | Vol. 14 No. 1 14 | Vol. • Checklist of the birds of Goa • Baltic Gull BIRDS Indian Indian BIRDS www.indianbirds.in VOL. 14 NO. 1 DATE OF PUBLICATION: 7 JANUARY 2018 ISSN 0973-1407 EDITOR: Aasheesh Pittie [email protected] CONTENTS ASSOCIATE EDITORS: V. Santharam, Praveen J. EDITORIAL BOARD Maan Barua, Anwaruddin Choudhury Bill Harvey, Farah Ishtiaq, Rajah Jayapal, Girish Jathar Ragupathy Kannan, Madhusudan Katti 1 A checklist of the birds of Goa, India R. Suresh Kumar, Taej Mundkur, Rishad Naoroji Pronoy Baidya & Mandar Bhagat Prasad Ganpule, Suhel Quader Harkirat Singh Sangha, C. Sashikumar Manoj Sharma, S. Subramanya, K. S. Gopi Sundar 32 The Baltic Gull Larus fuscus fuscus in Goa: An addition to the Indian avifauna David Williams & Martin Gottschling LAYOUT & COVER DESIGN: ShreeDesigns OffICE: P. Rambabu NEW ORNIS FOUNDATION Registration No. 314/2004 FOUNDER TRUSTEES Zafar Futehally (1920–2013) Aasheesh Pittie, V. Santharam TRUSTEES Aasheesh Pittie, V. Santharam, Rishad Naoroji, Taej Mundkur, S. Subramanya, Suhel Quader, Praveen J. AIMS & OBJECTIVES • To publish a newsletter that will provide a platform to birdwatchers for publishing notes and observations primarily on birds of South Asia. • To promote awareness of birdwatching amongst the general public. • To establish and maintain links/liaison with other associations or organized bodies in India or abroad whose objectives are in keeping with the objectives of the Trust (i.e. to support amateur birdwatchers with cash / kind for projects in ornithology). Volume 13 onwards Indian BIRDS is only available as PDFs on www.indianbirds.in. Both, individual papers, and entire issues can be downloaded free of cost. -

Species Included in Categories A, B & C Scientific

Species included in categories A, B & C Scientific name Race Category 1 Mute Swan Cygnus olor -- A / C1 2 Bewick’s Swan Cygnus columbianus bewickii A >> Tundra Swan columbianus -- 3 Whooper Swan Cygnus cygnus -- A 4 Bean Goose Anser fabalis fabilis A >> Tundra Bean Goose rossicus -- 5 Pink-footed Goose Anser brachyrhynchus -- A 6 White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons flavirostris A >> Russian White-fronted Goose albifrons -- 7 Lesser White-fronted Goose Anser erythropus -- A 8 Greylag Goose Anser anser anser A / C1 9 Snow Goose Anser caerulescens caerulescens A / D1 >> Greater Snow Goose atlanticus -- 10 Cackling Goose Branta hutchinsii hutchinsii A 11 Canada Goose Branta canadensis canadensis A / C1 >> Todd's Canada Goose interior -- 12 Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis -- A / C1 13 Brent Goose Branta bernicla hrota A >> Dark-bellied Brent Goose bernicla -- >> Black Brant nigricans -- 14 Ruddy Shelduck Tadorna ferruginea -- B / D1 15 Shelduck Tadorna tadorna -- A 16 Mandarin Duck Aix galericulata -- C1 17 Wigeon Anas penelope -- A 18 American Wigeon Anas americana -- A 19 Gadwall Anas strepera -- A 20 Baikal Teal Anas formosa -- A / D1 21 Teal Anas crecca crecca A 22 Green-winged Teal Anas carolinensis -- A 23 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos platyrhynchos A / C1 24 American Black Duck Anas rubripes -- A 25 Pintail Anas acuta acuta A 26 Garganey Anas querquedula -- A 27 Blue-winged Teal Anas discors -- A 28 Shoveler Anas clypeata -- A 29 Red-crested Pochard Netta rufina -- A 30 Pochard Aythya ferina -- A 31 Redhead Aythya americana -- A 32 Ring-necked -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

ORIGINAL ARTICLE: Do Invasive

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2010) 37, 1824–1834 ORIGINAL Do invasive species undergo ARTICLE metapopulation dynamics? A case study of the invasive Caspian gull, Larus cachinnans, in Poland Magdalena Lenda1*, Magdalena Zagalska-Neubauer2,3, Grzegorz Neubauer3 and Piotr Sko´rka4 1Institute of Nature Conservation, Polish ABSTRACT Academy of Sciences, Mickiewicza 33, 31-120 Aim The mechanisms of initial dispersal and habitat occupancy by invasive alien Krako´w, Poland, 2Institute of Environmental Sciences, Jagiellonian University, Gronostajowa species are fundamental ecological problems. Most tests of metapopulation 7, 30-387 Krako´w, Poland, 3Ornithological theory are performed on local population systems that are stable or in decline. In Station, Museum and Institute of Zoology, the current study we were interested in the usefulness of metapopulation theory Polish Academy of Sciences, Nadwis´lan´ska 108, to study patch occupancy, local colonization, extinction and the abundance of the 80-680 Gdan´sk, Poland, 4Institute of Zoology, invasive Caspian gull (Larus cachinnans) in its initial invasion stages. Poznan´ University of Life Sciences, Wojska Location Waterbodies in Poland. Polskiego 71 C, 60-625 Poznan´, Poland Methods Characteristics of the habitat patches (waterbodies, 35 in total) occupied by breeding pairs of Caspian gulls and an equal sample of randomly selected unoccupied patches were compared with t-tests. Based on presence– absence data from 1989 to 2006 we analysed factors affecting the probability of local colonization, extinction and the size of local populations using generalized linear models. Results Occupied habitat patches were significantly larger and less isolated (from other habitat patches and other local populations) and were located closer to rivers than empty patches. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Template for Submission of Scientific Information to Describe Areas Meeting Scientific Criteria for Ecologically Or Biologically Significant Marine Areas

Template for Submission of Scientific Information to Describe Areas Meeting Scientific Criteria for Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas Title/Name of the area: Ukrainian bays Abstract (in less than 150 words) Area located in the northern coast of the Black Sea, that encompasses 2 marine Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas mostly designated for the importance for several species of gulls, terns and seaducks. More than 1% of the global/biogeographic population of 10 seabird species occur in the area. The area encompasses also the non-breeding distribution of two Vulnerable seabirds – the Velvet Scoter Melanitta fusca and the Horned Grebe Podiceps auritus. Introduction Area located in the northern coast of the Black Sea (Figure 1), in the shallow waters (< 100 m deep) of the Ukranian bays of Yagorlyts'ka, Tendrivs'ka, Karkinits'ka and Dzharylgats'ka. The area includes 2 marine Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (Figure 1), mostly designated for the importance for several species of gulls, terns and seaducks. More than 1% of the global/biogeographic population of 10 seabird species occur in the area (Greater Scaup Aythya marila, Great White Pelican Pelecanus onocrotalus, Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo, Caspian Gull Larus cachinnans, Little Gull Hydrocoloeus minutus, Slender-billed Gull Larus genei, Mediterranean Gull Larus melanocephalus, Common Tern Sterna hirundo, Sandwich Tern Thalasseus sandvicensis and Caspian Tern Hydroprogne caspia: BirdLife International 2017a, 2017b). The area encompasses also the non- breeding distribution of two Vulnerable seabirds – the Velvet Scoter Melanitta fusca and the Horned Grebe Podiceps auritus (BirdLife International 2017c; Figure 2). Location The area is located in the North coast of Black Sea (ca. -

Laridaerefspart1 V1.2.Pdf

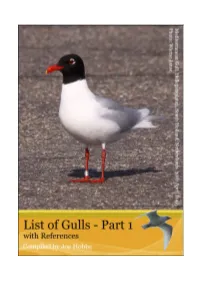

Introduction This is the first of two Gull Reference lists. It includes all those species of Gull that are not included in the genus Larus. I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2014 & 2015 to: [email protected]. Grateful thanks to Wietze Janse (http://picasaweb.google.nl/wietze.janse) and Dick Coombes for the cover images. All images © the photographers. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds.) 2014. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 4.2 accessed April 2014]). Cover Main image: Mediterranean Gull. Hellegatsplaten, South Holland, Netherlands. 30th April 2010. Picture by Wietze Janse. Vignette: Ivory Gull. Baltimore Harbour, Co. Cork, Ireland. 4th March 2009. Picture by Richard H. Coombes. Version Version 1.2 (August 2014). Species Page No. Andean Gull [Chroicocephalus serranus] 19 Audouin's Gull [Ichthyaetus audouinii] 37 Black-billed Gull [Chroicocephalus bulleri] 19 Black-headed Gull [Chroicocephalus ridibundus] 21 Black-legged Kittiwake [Rissa tridactyla] 6 Bonaparte's Gull [Chroicocephalus philadelphia] 16 Brown-headed Gull [Chroicocephalus brunnicephalus] 20 Brown-hooded Gull [Chroicocephalus maculipennis] 20 Dolphin Gull [Leucophaeus scoresbii] 31 Franklin's Gull [Leucophaeus pipixcan] 34 Great Black-headed Gull [Ichthyaetus ichthyaetus] 41 Grey Gull [Leucophaeus -

Species Boundaries in the Herring and Lesser Black-Backed Gull Complex J

Species boundaries in the Herring and Lesser Black-backed Gull complex J. Martin Collinson, David T. Parkin, Alan G. Knox, George Sangster and Lars Svensson Caspian Gull David Quinn ABSTRACT The BOURC Taxonomic Sub-committee (TSC) recently published recommendations for the taxonomy of the Herring Gull and Lesser Black-backed Gull complex (Sangster et al. 2007). Six species were recognised: Herring Gull Larus argentatus, Lesser Black-backed Gull L. fuscus, Caspian Gull L. cachinnans,Yellow-legged Gull L. michahellis, Armenian Gull L. armenicus and American Herring Gull L. smithsonianus.This paper reviews the evidence underlying these decisions and highlights some of the areas of uncertainty. 340 © British Birds 101 • July 2008 • 340–363 Herring Gull taxonomy We dedicate this paper to the memory of Andreas Helbig, our former colleague on the BOURC Taxonomic Sub-committee. He was a fine scientist who, in addition to leading the development of the BOU’s taxonomic Guidelines, made significant contributions to our understanding of the evolutionary history of Palearctic birds, especially chiffchaffs and Sylvia warblers. He directed one of the major research programmes into the evolution of the Herring Gull complex. His tragic death, in 2005, leaves a gap in European ornithology that is hard to fill. Introduction taimyrensis is discussed in detail below, and the Until recently, the Herring Gull Larus argentatus name is used in this paper to describe the birds was treated by BOU as a polytypic species, with breeding from the Ob River east to the at least 12 subspecies: argentatus, argenteus, Khatanga (Vaurie 1965). There has been no heuglini, taimyrensis, vegae, smithsonianus, molecular work comparing the similar and atlantis, michahellis, armenicus, cachinnans, intergrading taxa argentatus and argenteus barabensis and mongolicus (Vaurie 1965; BOU directly and any reference to ‘argentatus’ in this 1971; Grant 1986; fig.