Simulated Imperialism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SMALL TOWN AMERICAS: REPRESENTING the NATION in the MINIATURE TOURIST ATTRACTION, 1953-2014 by SAMANTHA JOHNSTON BOARDMAN A

SMALL TOWN AMERICAS: REPRESENTING THE NATION IN THE MINIATURE TOURIST ATTRACTION, 1953-2014 by SAMANTHA JOHNSTON BOARDMAN A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in American Studies written under the direction of Timothy F. Raphael and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ Newark, New Jersey MAY, 2015 2015 Samantha Johnston Boardman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Small Town Americas: Representing The Nation In The Miniature Tourist Attraction, 1953-2014 By SAMANTHA J. BOARDMAN Dissertation Director: Timothy F. Raphael Nationally themed miniature tourist attractions are popular destinations in many areas of the world, however there is currently no site in the U.S. exactly analogous to such locations as Madurodam, Mini Israel, or Italia in Miniatura. What the U.S. does have, however, is a history of numerous “American”-themed attractions employing scale models and miniature landscapes that similarly purport to represent an overview of the nation. Developments in travel infrastructure and communications technology, the decentralization of national tourism objectives and strategies, the evolution of tourism and tourist attractions in the nation and changing American cultural mores can all be seen in the miniature American landscapes investigated in this project. Significantly, while research has been conducted on the Miniaturk and Taman Mini Java parks and the ways in which they are constructed by/construct a particular view of national identity in Turkey and Indonesia respectively, no such study has looked at the meaning(s) contained in and conveyed by their American counterparts. -

A Critical Review of Ankapark, Ankara a Thesis

THEME PARK AS A SOCIO-CULTURAL AND ARCHITECTURAL PROGRAM: A CRITICAL REVIEW OF ANKAPARK, ANKARA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF THE MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY GÜN SU EYÜBOĞLU IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE IN ARCHITECTURE MAY 2018 Approval of the thesis: THEME PARK AS A SOCIO-CULTURAL AND ARCHITECTURAL PROGRAM: A CRITICAL REVIEW OF ANKAPARK, ANKARA submitted by GÜN SU EYÜBOĞLU in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture in Department of Architecture, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Halil Kalıpçılar Dean, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences Prof. Dr. F. Cânâ Bilsel Head of Department, Architecture Assoc. Prof. Dr. İnci Basa Supervisor, Architecture Dept., METU Examining Committee Members: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ela Alanyalı Aral Architecture Dept., METU Assoc. Prof. Dr. İnci Basa Architecture Dept., METU Prof. Dr. Zeynep Uludağ Architecture Dept., Gazi University Prof. Dr. Adnan Barlas City and Regional Planning Dept., METU Assist. Prof. Dr. Esin Kömez Dağlıoğlu Architecture Dept., METU Date: 09.05.2018 I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Gün Su Eyüboğlu Signature: iv ABSTRACT THEME PARK AS A SOCIO-CULTURAL AND ARCHITECTURAL PROGRAM: A CRITICAL REVIEW OF ANKAPARK, ANKARA Eyüboğlu, Gün Su M.Arch, Department of Architecture Supervisor: Assoc. -

Heterotopia And

1111 2 Heterotopia and the City 3 4 5111 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 3111 Heterotopia, literally meaning ‘other places’, is a rich concept in urban design 4 that describes a world off-center with respect to normal or everyday spaces, 5 one that possesses multiple, fragmented, or even incompatible meanings. The 6 term has had an impact on architectural and urban theory since it was coined 7 by Foucault in the late 1960s but has remained a source of confusion and 8 debate since. Heterotopia and the City seeks to clarify this concept and investi- 9 gates the heterotopias which exist throughout our contemporary world: in 20111 museums, theme parks, malls, holiday resorts, gated communities, wellness 1 hotels, and festival markets. 2 The book combines theoretical contributions on the concept of heterotopia, 3 including a new translation of Foucault’s influential 1967 text, Of Other Spaces, 4 with a series of critical case studies that probe a range of (post-) urban 5 transformations, from the ‘malling’ of the agora, through the ‘gating’ of dwelling, 6 to the ‘theming’ of urban renewal. Wastelands and terrains vagues are explored as sites of promise and resistance in a section on urban activism and trans- 7 gression. The reader gets a glimpse of the extremes of our dualized, postcivil 8 condition through case studies on Jakarta, Dubai, and Kinshasa. 9 Heterotopia and the City provides a collective effort to reposition heterotopia 30111 as a crucial concept for contemporary urban theory and redirects the current 1 debate on the privatization of public space. -

Shenzhen China Itinerary

Shenzhen China itinerary Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Shenzhen China itinerary Shenzhen china vacaon, the best things to do in Shenzhen: shenzhen mall, shenzhen zoo shenzhen market, shenzhen night market, shenzhen queen spa, shenzhen shopping centers and more... Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 1 - Arrival to Shenzhen Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 1 - Arrival to Shenzhen 1. Shenzhen Bao'an International Airport Bao'an, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China Telephone: +86 755 2345 6789 Website: www.szairport.com Rating: 3.8 2. Shenzhen Grand Theatre Shen Zhen Da Ju Yuan, CaiWuWei, Luohu Qu, Shenzhen Shi, Guangdong Sheng, China, 518000 3. CPC Diwang Mansion United Committee China, Guangdong, Shenzhen Shi, Luohu Qu, CaiWuWei, Shennan E Rd, 5002号信兴广场43层4317 邮政编码: 518001 4. Dongmen Pedestrian Street Pedestrian St, DongMen, Luohu Qu, Shenzhen Shi, Guangdong Sheng, China, 518000 Rating: 4.2 Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 2 - Shenzhen Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 2 - Shenzhen naonalies. It is one of the world's largest scenery parks 5. Dream Aquarium 1. Shenzhen more.. China, Guangdong, Shenzhen Shi, Nanshan Qu, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China HuaQiaoCheng, Baishi Rd, 白石路东8号欢乐海岸购物中心 2 层西侧 3. Hua Art Museum WIKIPEDIA Telephone: +86 755 8612 2132 Hua Mei Shu Guan, HuaQiaoCheng, Nanshan Qu, Shenzhen Shenzhenis a major city in Guangdong Province, China and one Rating: 2.8 Shi, Guangdong Sheng, China, 518053 of the four largest and wealthiest cies of China. The city is located immediately north of Hong Kong Special Administrave Region and holds sub-provincial administrave status, with powers slightly less than a province. -

The Use of Miniature Parks As a Museum for Egyptian Architectural Heritage

Current Science International Volume : 08 | Issue : 04| Oct.- Dec. | 2019 EISSN:2706-7920 ISSN: 2077-4435 Pages: 623-639 DOI: 10.36632/csi/2019.8.4.3 The use of miniature parks as a museum for Egyptian architectural heritage Nermin Mokhtar Farrag Civil & Architectural Department, Engineering Division, National Research Centre (NRC), 33 El- Buhouth St., 12622 Dokki, Giza, Egypt. E-mail: [email protected] Ayman Hesham Elalfy Civil & Architectural Department, Engineering Division, National Research Centre (NRC), 33 El- Buhouth St., 12622 Dokki, Giza, Egypt. E-mail: [email protected] Received: 30 July 2019/ Accepted 25 Sept. 2019 / Publication date: 15 Oct. 2019 ABSTRACT Miniature heritage parks are considered a good chance for people to be aware of their countries architectural heritage. It might be hard for every person to visit most of a country’s monumental places. Egypt is a country that has various historical places and a lot of monuments located in different natural and cultural environments. Egypt had passed various historical periods including pharaonic, Coptic and Islamic. Miniature heritage parks contain a blend of small scale architectural models and sculpture art models that compose a good knowledge environment that enhance its visitors to know about their heritage. Although Egypt has a very rich heritage environment. Yet there are few opened miniature heritage parks. Nowadays there is a great demand to enhance the design and construction of such parks with the guidance of the foreign miniature heritage parks found in China, Holland and the United States of America. The research goal is to enhance the architectural design process for heritage mini parks in Egypt through a comparative study for of some foreign park examples displaying Egyptian monumental models and two miniature heritage parks existing in Egypt reaching architectural design criteria that should be considered during the design process. -

US Edition 2020/21 Goway: the Only Way to Go to Asia

US Edition 2020/21 Goway: The Only Way To Go To Asia ” E XOTIC" is often used when describing Asia. Come on an unforgettable journey with the experts to Asia...an amazingly diverse continent, a land of mystery, legend, and a place where you can experience culture at its most magnificent. There is so much to see and do in Asia, mainly because it is so BIG! Marco Polo travelled for seven- teen years and didn’t see it all. My son completed a twelve month backpacking journey in Asia and only visited eight countries (including the two largest, India and China). If you have already been to Asia, you will know what I am saying. If you haven’t, you should go soon because you will want to keep going back. For our most popular travel ideas to visit Asia, please keep reading our brochure. When you travel with Goway you become part of a special fraternity of travellers of whom we care about Bruce and Claire Hodge in Varanasi very much. Our company philosophy is simple – we want you to be more than satisfied with our services so that (1) you will recommend us to your friends and (2) you will try one of our other great travel ideas. I personally invite you to join the Goway family BRUCE J. HODGE of friends who have enjoyed our services over the last 50 years. Come soon to exotic Asia… with Goway. Founder & President 2 Visit www.goway.com for more details Trans Siberian Railway Ulaan Baatar RUSSIA Karakorum MONGOLIA Tsar’s Gold Urumqi Turpan Beijing Kashgar Sea of Japan Dunhuang Seoul Gyeongju Tokyo Tibet SOUTH KOREA Kyoto Express Hakone CHINA East China -

Walgreens ™ 4181 Oceanside Blvd | Oceanside, CA Walgreens, Oceanside CA | 1 ™

OFFERING MEMORANDUM Walgreens ™ 4181 Oceanside Blvd | Oceanside, CA Walgreens, Oceanside CA | 1 ™ ® college boulevard SUBJECT PROPERTY oceanside boulevard traffic counts OCEANSIDE BOULEVARD......±31,792 VPD ™ COLLEGE2 | BOULEVARD...........±40,116Matthews Retail VPDAdvisors contents ® 04 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 06 financial OVERVIEW 10 tenant overview college boulevard 14 area OVERVIEW exclusively listed by SUBJECT PROPERTY CAITLIN ZIRPOLO college boulevard ASSOCIATE SHOPPING CENTERS [email protected] DIR (949) 432-4518 MOB (760) 685-6873 LIC # 01987844 SUBJECT PROPERTY el warner SVP & NATIONAL DIRECTOR SHOPPING CENTERS [email protected] DIR (310) 579-9690 oceanside boulevard oceanside boulevard MOB (858) 752-3078 LIC # 01890271 kyle matthews CHAIRMAN AND CEO BROKER OF RECORD [email protected] DIR (310) 919-5757 MOB (310) 622-3161 LIC # 01469842 Walgreens, Oceanside CA | 3 executive summary offering summary Matthews National Retail Investment Group-West is pleased to present the absolute triple-net (NNN) ground lease sale of Walgreens, located in North County San Di- ego, city of Oceanside, California. Situated on the hard corner of College Boulevard and Oceanside Boulevard, this asset benefits from its location in a densely popu- lated submarket with strong demographics. This is an excellent opportunity for an investor to acquire an attractive, low risk-asset in the heart of Southern California. Outparceled to Del Oro Marketplace, this irreplaceable retail location provides an investor a long 19-year lease term with -

Beautiful, Good, Important and Special Cultural Heritage, Archaeology, Tourism and the Miniature in the Holy Land

Beautiful, Good, Important and Special Cultural Heritage, Archaeology, Tourism and the Miniature in the Holy Land Morag M. Kersel and Yorke M. Rowan Abstract Through an examination of representations of cultural heritage in miniature this paper tackles the recurrent question of how are culture, a nation, and the past presented to the public. Exploring how this is achieved at the microcosm of Mini Israel, an outdoor park mid- way between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv where you can “see it all small” (Shapira 2003: 1), we con- clude that Mini Israel offers visitors (foreign or local) what they want; an unthreatening version of the Holy Land, where differences in ethnicities, religions, and political groups are abridged in a pristine environment free from conflict and strife. At Mini Israel displays include the commercial, the contemporary, and the ancient, depicting what is “beautiful, good, important, and special” (Shapira 2003: 2). We argue that the selection of sites in miniature is a reflection of tourism trends, financial motives, and visitor preference, rather than a reflection of facts on the ground. Resumen Mediante un análisis de representaciones del patrimonio cultural en miniatura, este artículo aborda la pregunta recurrente de cómo una cultura, una nación y el pasado se pre- sentan al público. Investigando cómo se logra esto en el microcosmo de Mini Israel, un parque al aire libre a mitad de camino entre Jerusalén y Tel Aviv donde se puede “ver todo pequeño” (Shapira 2003: 1), llegamos a la conclusión de que Mini Israel ofrece a los visitantes (extranjeros o locales) lo que ellos desean: una versión inofensiva de la Tierra Santa, donde las diferencias étnicas, religiosas y políticas están reducidas en un entorno inmaculado libre de conflictos y disputas. -

17.2 TDSR Interior Pages Final

TDSR VOLUME XVII NUMBER II 2006 55 Modeling Citizenship in Turkey’s Miniature Park . IPEK TÜRELI This article discusses the design and wider political significance of Miniaturk, a nonprofit cul- tural heritage site that opened in Istanbul in 2003. It analyzes how image, publicity, and architectural form have come together to rework memory to conform to a new perceived rela- tionship between citizens and the Turkish state. As a site of architectural miniatures, Miniaturk provides an escape from the experience of the everyday. But it also must be under- stood in dialectic relation to gigantic new sites of global capital around the city. Miniature parks are a global type with a long history. The article seeks to understand why a miniature Turkey has only just appeared, and why it has been received with such enthusiasm in the con- text of contemporary Turkish politics. How can its appeal be interpreted in relation to compa- rable sites? As a cultural “showcase,” how does it represent Istanbul, Turkey, and the concept of Turkish citizenship? The Municipality of Istanbul has aroused great controversy recently by its willingness to play host to the giant building proposals of global capital. As the city acquires transpar- ent new buildings of steel and glass, immense public debate has been excited by an ironic lack of transparency in the web of international investment behind them. Yet, only three years ago, the Istanbul Municipality was applauded for its new minia- ture “heritage” park, Miniaturk. The park exhibits scale models of architectural show- pieces chosen for their significance in the city’s and Turkey’s collective memory (fig.1). -

Modelling Citizenship in Turkey's Miniature Park Ipek Tdreli

Chapter 6 Modelling Citizenship in Turkey's Miniature Park Ipek TDreli The Golden Horn (Hali«) suffered over a long period from industrial pollution. Its rehabilitation became an issue as early as the 1960s. In the second half of the 1980s, the government carried out a 'cleaning' operation which also involved major and swift demolition of properties crowding its shoreline. Green parks were created on reclaimed land along the shores but they remained desolate because of the lack of activity. Then the government started encouraging cultural investment around the Golden Horn. Miniaturk, Turkey's first nation-themed park of miniature models, which opened in 2003, is part of the latter phase of this urban regeneration campaign which focuses on culture-led revitalization (figure 6.1). As its name makes plain, Miniaturk presents a 'Turkey in miniature'. Its main outdoor display area features 1/25-scaled models of architectural showpieces chosen for their significance in the city's and Turkey'S history. As a site of architectural miniatures, Miniaturk provides an escape from the experience of the everyday. But it must also be understood in dialectic relation to gigantic new sites of global capital as well as to gigantic older sites of nation building. This chapter seeks to interpret why a miniature Turkey appeared in 2003, and why it has been received with enthusiasm across the political spectrum.! Similar miniature theme parks abound around the world and reveal much about the contexts in which they are situated. Private enterprises like Disneyland have become hallmarks of national experience. Other, state-controlled examples may attempt more explicitly to reconfigure the relationship between a nation and its citizens. -

SARE, Vol. 58, Issue 1 | 2021

SARE, Vol. 58, Issue 1 | 2021 Creating Cultural and Historical Imaginaries in Physical Space: Worldbuilding in Chinese Theme Parks Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, Orlando, USA Abstract Theme parks are fascinating texts built on spatial narratives and detailed storyworlds. Worldbuilding and subcreation are literal in these spaces, but they likewise contain symbolic experiences that represent cultural and historical imaginaries. China is one of the largest markets in the global theme park industry. The design ethos in many parks is to represent fantasy versions of reality or depict cultural beliefs. This article offers analysis of examples in Chinese parks that signify simulated place or culture (for example, Splendid China’s parks), a romanticized historical time (the Songcheng parks), local stories (Sunac Land parks), and national cultural stories (the Fantawild Oriental Heritage model). Each of these spaces presents narratives and immersive environments that have the power to engage visitors on physical, sensual, conceptual, and emotional levels. They are second worlds to play in, imagine in, and to consume fantasy in while also providing a shifting model of theme park experience. Keywords: theme parks, China, worldbuilding, subcreation, immersion, culture China is one of the largest markets in the global theme park industry and it was expected to have the largest attendance in 2020, had the pandemic not interfered with the industry’s trajectory (Rubin 44). Perhaps because of a lack of familiarity with the Chinese industry, the most common discussions within scholarship in English have tended towards the arrival of Western brands such as Disney and Universal into China. After exploring concepts of worldbuilding and immersion, this article provides details of several examples of this practice in Chinese theme parks by examining the parks of four major operators. -

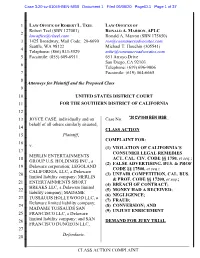

Case 3:20-Cv-01049-BEN-MSB Document 1 Filed 06/08/20 Pageid.1 Page 1 of 37

Case 3:20-cv-01049-BEN-MSB Document 1 Filed 06/08/20 PageID.1 Page 1 of 37 1 LAW OFFICE OF ROBERT L. TEEL LAW OFFICES OF Robert Teel (SBN 127081) RONALD A. MARRON, APLC 2 [email protected] Ronald A. Marron (SBN 175650) 3 1425 Broadway, Mail Code: 20-6690 [email protected] Seattle, WA 98122 Michael T. Houchin (305541) 4 Telephone: (866) 833-5529 [email protected] 5 Facsimile: (855) 609-6911 651 Arroyo Drive San Diego, CA 92103 6 Telephone: (619) 696-9006 7 Facsimile: (619) 564-6665 8 Attorneys for Plaintiff and the Proposed Class 9 10 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 11 FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 12 13 JOYCE CASE, individually and on Case No: '20CV1049 BEN MSB behalf of all others similarly situated, 14 CLASS ACTION 15 Plaintiff, COMPLAINT FOR: 16 v. (1) VIOLATION OF CALIFORNIA’S 17 CONSUMER LEGAL REMEDIES MERLIN ENTERTAINMENTS 18 ACT, CAL. CIV. CODE §§ 1750, et seq.; GROUP U.S. HOLDINGS INC., a (2) FALSE ADVERTISING, BUS. & PROF. 19 Delaware corporation; LEGOLAND CODE §§ 17500, et seq.; CALIFORNIA, LLC, a Delaware 20 (3) UNFAIR COMPETITION, CAL. BUS. limited liability company; MERLIN & PROF. CODE §§ 17200, et seq.; 21 ENTERTAINMENTS SHORT (4) BREACH OF CONTRACT; BREAKS LLC, a Delaware limited 22 (5) MONEY HAD A RECEIVED; liability company; MADAME (6) NEGLIGENCE; 23 TUSSAUDS HOLLYWOOD LLC, a (7) FRAUD; Delaware limited liability company; 24 (8) CONVERSION; AND MADAME TUSSAUDS SAN (9) UNJUST ENRICHMENT 25 FRANCISCO LLC, a Delaware limited liability company; and SAN 26 DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL FRANCISCO DUNGEON LLC, 27 Defendants.