Unit 9 Dance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meaning of Shivataandava Stotra

meaning of shivataaNDava stotra ¡£¢ ¤¦¥¨§ © § §§ (' ¢ § ¥¨§ § § !§#"$§¤&% §)" *+§,§.-/ matted hair-thick as forest-water-flow-consecrated-areaD +1 :9 ;£< < A B0 ¥0§# %2§§#§4365 §)7 38* § §>=(?* §@=(?+§ C in the throat-stuck-hanging-snake-lofty-garland ON 9 E E E E E §+§ §GF§ §GF§ §GFHI§JLKM §%2§ §PF§RQ§TS § DD damat-damat-damat-damat-having sound-drum-thisDDZY B0 9 < ¡ ¡ U U V § Q§ §6© F ©WFH%2§ *+§LX * § § %2§ %2§>C did-fierce-Tandava-may he shower-on us-Siva- auspiciousness With his neck, consecrated by the flow of water flowing from the thick forest-like locks of hair, and on the neck, where the lofty snake is hanging garland, and the Damaru drum making the sound of Damat Damat Damat Damat, Lord Siva did the auspi- cious dance of Tandava and may He shower prosperity on us all. WB W' 9 ; ; A ¢ §[ § ,§ ¤&§§ ¤&§RJLK§ §]\OJWQ§_^ ` § - matted hair-a well-agitation-moving-celestialD river ¢+b ¢ %2§§ c¦` dQ aX §# §§ §[ § X Q§fegJ - agitating-waves-rows-glorified-head N N B¨ h §+¥0§ §.eg¥¨§ §.e/¥¨§ § iSjH§ § ck "$§jlm" %2§ v DD Dhagat dhagat dhagat-flaming-forehead-flatDuD area-fire +p 9 n U X Q§ §6§.o ¤ Q Q§q¦ "$§¤¦q4rs§#© I§t§ baby-moon-crest jewel-love-every moment-for me I have a very deep interest in Lord Siva, whose head is glo- rified by the rows of moving waves of the celestial river Ganga, ag- itating in the deep well of his hair-locks, and who has the brilliant fire flam- ing on the surface of his forehead, and who has the crescent moon as a jewel on his head. -

Indian Classical Dance Is a Relatively New Umbrella Term for Various Codified Art Forms Rooted in Natya, the Sacred Hindu Musica

CLASSICAL AND FOLK DANCES IN INDIAN CULTURE Palkalai Chemmal Dr ANANDA BALAYOGI BHAVANANI Chairman: Yoganjali Natyalayam, Pondicherry. INTRODUCTION: Dance in India comprises the varied styles of dances and as with other aspects of Indian culture, different forms of dances originated in different parts of India, developed according to the local traditions and also imbibed elements from other parts of the country. These dance forms emerged from Indian traditions, epics and mythology. Sangeet Natak Akademi, the national academy for performing arts, recognizes eight distinctive traditional dances as Indian classical dances, which might have origin in religious activities of distant past. These are: Bharatanatyam- Tamil Nadu Kathak- Uttar Pradesh Kathakali- Kerala Kuchipudi- Andhra Pradesh Manipuri-Manipur Mohiniyattam-Kerala Odissi-Odisha Sattriya-Assam Folk dances are numerous in number and style, and vary according to the local tradition of the respective state, ethnic or geographic regions. Contemporary dances include refined and experimental fusions of classical, folk and Western forms. Dancing traditions of India have influence not only over the dances in the whole of South Asia, but on the dancing forms of South East Asia as well. In modern times, the presentation of Indian dance styles in films (Bollywood dancing) has exposed the range of dance in India to a global audience. In ancient India, dance was usually a functional activity dedicated to worship, entertainment or leisure. Dancers usually performed in temples, on festive occasions and seasonal harvests. Dance was performed on a regular basis before deities as a form of worship. Even in modern India, deities are invoked through religious folk dance forms from ancient times. -

Odissi Dance

ORISSA REFERENCE ANNUAL - 2005 ODISSI DANCE Photo Courtesy : Introduction : KNM Foundation, BBSR Odissi dance got its recognition as a classical dance, after Bharat Natyam, Kathak & Kathakali in the year 1958, although it had a glorious past. The temple like Konark have kept alive this ancient forms of dance in the stone-carved damsels with their unique lusture, posture and gesture. In the temple of Lord Jagannath it is the devadasis, who were performing this dance regularly before Lord Jagannath, the Lord of the Universe. After the introduction of the Gita Govinda, the love theme of Lordess Radha and Lord Krishna, the devadasis performed abhinaya with different Bhavas & Rasas. The Gotipua system of dance was performed by young boys dressed as girls. During the period of Ray Ramananda, the Governor of Raj Mahendri the Gotipua style was kept alive and attained popularity. The different items of the Odissi dance style are Mangalacharan, Batu Nrutya or Sthayi Nrutya, Pallavi, Abhinaya & Mokhya. Starting from Mangalacharan, it ends in Mokhya. The songs are based upon the writings of poets who adored Lordess Radha and Krishna, as their ISTHADEVA & DEVIS, above all KRUSHNA LILA or ŎRASALILAŏ are Banamali, Upendra Bhanja, Kabi Surya Baladev Rath, Gopal Krishna, Jayadev & Vidagdha Kavi Abhimanyu Samant Singhar. ODISSI DANCE RECOGNISED AS ONE OF THE CLASSICAL DANCE FORM Press Comments :±08-04-58 STATESMAN őIt was fit occasion for Mrs. Indrani Rehman to dance on the very day on which the Sangeet Natak Akademy officially recognised Orissi dancing -

Guide to 275 SIVA STHALAMS Glorified by Thevaram Hymns (Pathigams) of Nayanmars

Guide to 275 SIVA STHALAMS Glorified by Thevaram Hymns (Pathigams) of Nayanmars -****- by Tamarapu Sampath Kumaran About the Author: Mr T Sampath Kumaran is a freelance writer. He regularly contributes articles on Management, Business, Ancient Temples and Temple Architecture to many leading Dailies and Magazines. His articles for the young is very popular in “The Young World section” of THE HINDU. He was associated in the production of two Documentary films on Nava Tirupathi Temples, and Tirukkurungudi Temple in Tamilnadu. His book on “The Path of Ramanuja”, and “The Guide to 108 Divya Desams” in book form on the CD, has been well received in the religious circle. Preface: Tirth Yatras or pilgrimages have been an integral part of Hinduism. Pilgrimages are considered quite important by the ritualistic followers of Sanathana dharma. There are a few centers of sacredness, which are held at high esteem by the ardent devotees who dream to travel and worship God in these holy places. All these holy sites have some mythological significance attached to them. When people go to a temple, they say they go for Darsan – of the image of the presiding deity. The pinnacle act of Hindu worship is to stand in the presence of the deity and to look upon the image so as to see and be seen by the deity and to gain the blessings. There are thousands of Siva sthalams- pilgrimage sites - renowned for their divine images. And it is for the Darsan of these divine images as well the pilgrimage places themselves - which are believed to be the natural places where Gods have dwelled - the pilgrimage is made. -

All in One Gs 06 फेब्रुअरी 2019

ALL IN ONE GS 06 FEBRUARY 2019 Classical Dance in India: 3. Yajurveda / यजुर्ेद 4. Rigveda / ऋग्र्ेद Ans- 2 भारत मᴂ शास्त्रीय न配ृ य: Q-2 The oldest form of the composition of Hindustani Vocal Music is: Classical Dances are based on Natya Shastra. सहंदुस्तानी गायन संगीत की रचना का सबसे पुराना 셂प है: शास्त्रीय नृ配य नाट्य शास्त्र पर आधाररत होते हℂ। 1. Ghazal / ग़ज़ल 2. Dhrupad / ध्रुपद Classical dances can only be performed by trained dancers and who have 3. Thumri / ठुमरी 4. Qawwali / कव्र्ाली studied their form for many years. Ans- 2 शास्त्रीय नृ配य के वल प्रशशशित नततशकयⴂ द्वारा शकया जा सकता है और शजन्हⴂने कई वर्षⴂ तक Q-3 Which of the following is correct? अपने 셁पⴂ का अध्ययन शकया है। सन륍न में से कौन सा सही है? Classical dances have very particular meanings for each step, known as 1. Hojagiri dance- Tripura / होजासगरी नृ配य- सिपुरा "Mudras". 2. Bhavai dance- Rajasthan / भर्ई नृ配य- राजस्थान शास्त्रीय नृ配यⴂ के प्र配येक चरण के शलए बहुत शवशेर्ष अर्त होते हℂ, शजन्हᴂ "मुद्रा" के 셂प मᴂ 3. Karakattam- Tamil Nadu / करकटम- तसमलनाडु जाना जाता है। 4. All of the above / उपरोक्त सभी Classical dance forms are based on grace and formal gestures, steps, and Ans- 4 poses. Q-4 Which of the musical instruments is of Indo-Islamic origin? शास्त्रीय नृ配य 셂पⴂ अनुग्रह और औपचाररक इशारⴂ, और हाव-भाव पर आधाररत होते हℂ। कौन सा र्ाद्ययंि इडं ो-इस्लासमक मूल का है? 1. -

Classical Dances Have Drawn Sustenance

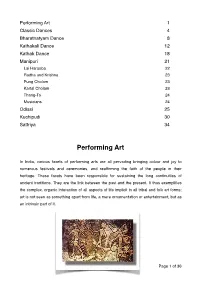

Performing Art 1 Classic Dances 4 Bharatnatyam Dance 8 Kathakali Dance 12 Kathak Dance 18 Manipuri 21 Lai Haraoba 22 Radha and Krishna 23 Pung Cholam 23 Kartal Cholam 23 Thang-Ta 24 Musicians 24 Odissi 25 Kuchipudi 30 Sattriya 34 Performing Art In India, various facets of performing arts are all pervading bringing colour and joy to numerous festivals and ceremonies, and reaffirming the faith of the people in their heritage. These facets have been responsible for sustaining the long continuities of ancient traditions. They are the link between the past and the present. It thus exemplifies the complex, organic interaction of all aspects of life implicit in all tribal and folk art forms; art is not seen as something apart from life, a mere ornamentation or entertainment, but as an intrinsic part of it. Page !1 of !36 Pre-historic Cave painting, Bhimbetka, Madhya Pradesh Under the patronage of Kings and rulers, skilled artisans and entertainers were encouraged to specialize and to refine their skills to greater levels of perfection and sophistication. Gradually, the classical forms of Art evolved for the glory of temple and palace, reaching their zenith around India around 2nd C.E. onwards and under the powerful Gupta empire, when canons of perfection were laid down in detailed treatise - the Natyashastra and the Kamasutra - which are still followed to this day. Through the ages, rival kings and nawabs vied with each other to attract the most renowned artists and performers to their courts. While the classical arts thus became distinct from their folk roots, they were never totally alienated from them, even today there continues a mutually enriching dialogue between tribal and folk forms on the one hand, and classical art on the other; the latter continues to be invigorated by fresh folk forms, while providing them with new thematic content in return. -

7 CHAPTER 1.Pdf

1 In general day to day life, if you describe someone as dynamic, you approve of them because they are full of energy or full of new and exciting ideas. The dynamic of a system or process is the force that causes it to change or progress. 'Dynamic' is used as an adjective, except when it means "motivating force", while 'dynamics' is always used as a noun meaning 'functioning' and 'development'. I think that, in the case of my research work, 'dynamics' is better suited than 'dynamic'. In contemporary India n society, a revitalisation of ‘traditional’ dances can be observed which manifests in the proliferation of dance schools and institutions, especially in urban areas. This revival was part of the drive, which has characterised India, to reconstruct itself after the traumatic colonial rule of 200 years. It was to create a new, unified nation that strives to be ‘modern’ and integrated into the global market economy. Here in the thesis I try to explore the repertoire and dynamics of one of the eight accepted classical dance styles, which is Bharatanatyam and its repertoire that is the Margam , as it embodies the new national identity. I have also tried looking into and pointing to the practices and views of gurus, teachers, scholars and dancers trained in the pre-colonial period and those from contemporary times with respect to the structure of the Margam . My research concentrates and is limited to looking and exploring the dynamics of changes in the format and structure of the Bharatanatyam Margam . The postures of classical dancer obey and follow strict rules established by tradition while following the mechanical rules of the body. -

The Role of Indian Dances on Indian Culture

www.ijemr.net ISSN (ONLINE): 2250-0758, ISSN (PRINT): 2394-6962 Volume-7, Issue-2, March-April 2017 International Journal of Engineering and Management Research Page Number: 550-559 The Role of Indian Dances on Indian Culture Lavanya Rayapureddy1, Ramesh Rayapureddy2 1MBA, I year, Mallareddy Engineering College for WomenMaisammaguda, Dhulapally, Secunderabad, INDIA 2Civil Contractor, Shapoor Nagar, Hyderabad, INDIA ABSTRACT singers in arias. The dancer's gestures mirror the attitudes of Dances in traditional Indian culture permeated all life throughout the visible universe and the human soul. facets of life, but its outstanding function was to give symbolic expression to abstract religious ideas. The close relationship Keywords--Dance, Classical Dance, Indian Culture, between dance and religion began very early in Hindu Wisdom of Vedas, etc. thought, and numerous references to dance include descriptions of its performance in both secular and religious contexts. This combination of religious and secular art is reflected in the field of temple sculpture, where the strictly I. OVERVIEW OF INDIAN CULTURE iconographic representation of deities often appears side-by- AND IMPACT OF DANCES ON INDIAN side with the depiction of secular themes. Dancing, as CULTURE understood in India, is not a mere spectacle or entertainment, but a representation, by means of gestures, of stories of gods and heroes—thus displaying a theme, not the dancer. According to Hindu Mythology, dance is believed Classical dance and theater constituted the exoteric to be a creation of Brahma. It is said that Lord Brahma worldwide counterpart of the esoteric wisdom of the Vedas. inspired the sage Bharat Muni to write the Natyashastra – a The tradition of dance uses the technique of Sanskrit treatise on performing arts. -

Final Senior Fellowship Report

FINAL SENIOR FELLOWSHIP REPORT NAME OF THE FIELD: DANCE AND DANCE MUSIC SUB FIELD: MANIPURI FILE NO : CCRT/SF – 3/106/2015 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF TWO VAISHNAVISM INFLUENCED CLASSICAL DANCE FORM, SATRIYA AND MANIPURI, FROM THE NORTH EAST INDIA NAME : REKHA TALUKDAR KALITA VILL – SARPARA. PO – SARPARA. PS- PALASBARI (MIRZA) DIST – KAMRUP (ASSAM) PIN NO _ 781122 MOBILE NO – 9854491051 0 HISTORY OF SATRIYA AND MANIPURI DANCE Satrya Dance: To know the history of Satriya dance firstly we have to mention that it is a unique and completely self creation of the great Guru Mahapurusha Shri Shankardeva. Shri Shankardeva was a polymath, a saint, scholar, great poet, play Wright, social-religious reformer and a figure of importance in cultural and religious history of Assam and India. In the 15th and 16th century, the founder of Nava Vaishnavism Mahapurusha Shri Shankardeva created the beautiful dance form which is used in the act called the Ankiya Bhaona. 1 Today it is recognised as a prime Indian classical dance like the Bharatnatyam, Odishi, and Kathak etc. According to the Natya Shastra, and Abhinaya Darpan it is found that before Shankardeva's time i.e. in the 2nd century BC. Some traditional dances were performed in ancient Assam. Again in the Kalika Purana, which was written in the 11th century, we found that in that time also there were uses of songs, musical instruments and dance along with Mudras of 108 types. Those Mudras are used in the Ojha Pali dance and Satriya dance later as the “Nritya“ and “Nritya hasta”. Besides, we found proof that in the temples of ancient Assam, there were use of “Nati” and “Devadashi Nritya” to please God. -

Paper on Expression of Advaita Vedanta Through Classical Music

Paper on Expression of Advaita Vedanta through Classical Music Advaitic kritis composed by Swami Dayānanda Saraswati (1930 - 2015) of Arsha Vidya Gurukulam -By Sonali Ambasankar Rarely will there be any person who has not heard of the kriti Bho Śambho Śiva Śambho Svayambho. Composed and written by Pujya Swami Dayānanda Saraswati (1930 - 2015), who established the Arsha Vidya Gurukulam, it is an immensely melodious and a much popular composition on Lord Śiva. So much is the popularity, that the song is sung by many a singer without even knowing the composer and the writer of these wonderful lyrics. It probably reflects the greatness of Swami Dayānanda ji as a teacher, where he wants the teaching to be remembered over the teacher, the song to be remembered over the composer. Swamiji composed many such Sanskrit kritis, in praise of different devatas. 19 kritis to be precise to be sung upon Gaṇapati, Someśvara, Śāradādevi, Mi̇̄nākśi, Ṣaṇmukham, Rāma, Govinda, Dakshināmurty, ĀdiŚankara and even on our dearest Bhāratavarsha. The last of his compositions was on Devi Jñāneśwari, in praise of the Veda, our Śruti māta. Across all his kritis, Swamiji has beautifully woven together Saguna and Nirguna Brahman. At first glance, these might appear as simple compositions like many others, sung as praises on different deities. But taking a closer look reveals a lot more. In the Bhagavad Gitā, Chapter 7, verse 16, Bhagavān Krṣṇā talks about the 4 bhaktas - ārta, arthārthi, jijñāsu and the jnāni. Each type of bhakta is seeking or connecting with Bhagavān through his own understanding of Bhagavān. ĀdiŚankara in his bhāsya on the Gitā says चतुवधाः चतुःकाराः भजते सेवंते मां जनाः सुकृतनः पुयकमाणः हे अजुन । आतः आतपरगृहतः तकरयारोगादना अभभूतः आपनः, िजासुः भगववं ातुमछत यः, अथाथ धनकामः, ानी वणोः तववच हे भरतषभ ॥ ७.१६ ॥ Swami Dayānandaji's compositions connect with each of these 4 types of bhaktas to his personal understanding of Bhagavān. -

Bhagavata Mela Dance-Drama of Bharata Natya

BHAGAVATA MELA DANCE-DRAMA OF BHARATA NATYA E. Krishna Iyer The classical dance-drama of the Bhagavata Mela tradition which is struggling for survival in the Tanjore District is a rare art of great value. Its revival will not only add one more rich variety to our existing dance arts but also help to clear away many prevailing misconceptions about Bharata Natya, by proving, that it is not confined to, or exhausted by, the solo Sadir-Natya of women and that it has a dramatic form too with many male and female characters expounding great Puranic themes and rasas other than Sringara as well. In short it will be found as an exemplifica tion of the 2000-year old conception of Natya as dance-drama according to the Natyasastra. Incidentally it may also prove the art to be a source of rich material to help the creation or evolution' of new forms of dance drama and ballet. Bharata Natya, properly understood, is a vast, comprehensive and generic system of classical dance in India, the principles and technique of which are closely applied to three chief forms among others namely; (1)the lyrical solo Sadir nautch, (2) the heavy Bhagavata Me/a dance-drama and (3) the light Kuravanji ballet. Of these, only the first has become widely popular and is called by the generic name itself. Early Origins The Bhagavata Mela Dance-Drama tradition seems to have been in vogue in this country from the 1lth century A.D. ifnot earlier. It is known to have come into prominence in South India from the time of Thirtha narayana Yogi, the author of Krishna Lee/a Tharangini who migrated from Andhra Desa, lived 'and died at Varahur in the Tanjore District about The late 'Shri E. -

Bridging the Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances As a Source of Dance/Movement Therapy, a Literature Review

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses (GSASS) Spring 5-16-2020 Bridging The Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances as a source of Dance/Movement Therapy, A Literature Review. Ruta Pai Lesley University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses Part of the Art Education Commons, Counseling Commons, Counseling Psychology Commons, Dance Commons, Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pai, Ruta, "Bridging The Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances as a source of Dance/Movement Therapy, A Literature Review." (2020). Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses. 234. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses/234 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences (GSASS) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. BRIDGING THE GAP 1 Bridging the Gap: Exploring Indian Classical Dances as a source of Dance/Movement Therapy, A Literature Review. Capstone Thesis Lesley University August 5, 2019 Ruta Pai Dance/Movement Therapy Meg Chang, EdD, BC-DMT, LCAT BRIDGING THE GAP 2 ABSTRACT Indian Classical Dances are a mirror of the traditional culture in India and therefore the people in India find it easy to connect with them. These dances involve a combination of body movements, gestures and facial expressions to portray certain emotions and feelings.