Cosmetic Compliance and the Failure of Negotiated Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To the D.Irector of the Bureau of Land Management NM State Office April

To the D.irector of the Bureau of Land Management NM State Office April 28, 2019 BLM, NMSO SANTA FE RECEIVED BLM New Mexico State Office APR,;~,5o 2019 Attention: State Director PAID RECEIPT # _ 301 Dinosaur Trail Santa Fe, NM 87508 We are writing to ask you to stop the proposed lease sale of lands near Chaco Canyon slated for June 2019. Fossil fuel exploration on these sites is a threat to the people who live on the surrounding land and to Chaco Canyon, New Mexico's crown jewel and the ancestral home of Native Americans of the Southwest. Protection from oil and gas activity around Chaco Canyon is essential to protecting New Mexico's uhique history, environment and vital resources. Instead of continuing to develop fossil fuels on our public lands, we need to make a just transition to renewable energy to create ways to engage in environmentally sustainable, as well as culturally appropriate, economic development. We ask you to cancel the lease sale of parcels: NM-201906-012-24; 26-46; 48-51 and NM-201906-025 & 47 to protect Chaco Canyon and the Greater Chaco Region from oil and gas activities that could destroy this designated World Heritage Site, a landmark like no other on Earth. Attached: 11,962 requests for your attention to this matter. First Name Last Name City State Zip Code Daniel Helfman 6301 MAURY HOLW TX 78750-8257 Kenneth Ruby 18Tiffany Road NH 03079 Crystal Newcomer 2350 Dusty Ln PA 17025 Timothy Post 1120 PacificAve KS 66064 Marlena Lange 23 RoyceAve NY 10940-4708 Victoria Hamlin 3145 MaxwellAve CA 94619 L. -

Taylor & Francis Reference Style C

Taylor & Francis Reference Style C CSE Name-Year CSE citations are widely used for scientific journals and are based on international principles adopted by the National Library of Medicine. There are three major systems for referring to a reference within the text. This one is the name-year system, where in-text references consist of the surname of the author or authors and the year of publication of the document. There are several advantages of this system. It is easier to add and delete references. Authors are recognized in the text, and the date provided with the author name may provide useful information for the reader. Also, since the reference list is arranged alphabetically by author, it is easy to locate works by specific authors. The main disadvantage of this system relates to the numerous rules that must be followed to form an in-text reference. Also, long strings of in-text references interrupt the text and may be irritating to the reader. This guide is based on Scientific Style and Format: The CSE Manual for Authors, Editors, and Publishers, 7th edition, 2006. Note that examples in the CSE manual follow the citation-name system, so need to be converted if you are using the name-year system. EndNote for Windows and Macintosh is a valuable all-in-one tool used by researchers, scholarly writers, and students to search online bibliographic databases, organize their references, and create bibliographies instantly. There is now an EndNote output style available if you have access to the software in your library (please visit http://www.endnote.com/support/enstyles.asp and look for TF-C CSE Name-Year). -

Of Surnames in the Tevis Family, a Family History by Mary M

Online Connections Genealogy Across Indiana Index of Surnames in The Tevis Family, a Family History by Mary M. Bell Karen M. Wood The Tevis Family, by Professor Emeritus Mary M. Bell of Northern Illinois University, accounts for the family’s history from the early eighteenth century until the twentieth century. The book is more than just a list of names and dates allowing for a glimpse into the characters and personalities of these descendants. Photographs are also included, and the second edition offers a list of lost sons and daughters, asking readers to send any available information regarding these Tevis descendants. The Tevis name is first recorded in the United States on April 5, 1707, when Robert Tevis married Susanna Davies in All Hallows Parish in Ann Arundel County, Maryland. The family then spread westward. In Indiana, they settled mainly in Rush, Shelby, and Jefferson counties, but also in Clark, Decatur, Tipton, and White counties. Of course, throughout the years, many other surnames have been added to the Tevis family tree due to daughters marrying into other families. The following pages list a comprehensive index of all surnames in the back of Bell’s The Tevis Family. Copies of the book are available by purchase from the author; for more information, please contact Teresa Baer, Managing Editor, of Family History Publications, at [email protected] Notes 1. Mary M. Bell, The Tevis Family, 2nd ed., ([ Camden, ME?]: Penobscot Press, 2009); Mary M. Bell to Teresa Baer, September 11, 2009. Index of Surnames in The Tevis -

Taylor & Francis Standard Reference Style: Chicago Author-Date

Taylor & Francis Standard Reference Style: Chicago author-date The author-date system is widely used in the physical, natural and social sciences. For full information on this style, see The Chicago Manual of Style (16th edn) or http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html (click on the tab marked author-date to ensure you are using the right style): Contents of this guide References in the text Tables and figures Reference list Book Journal Conference Thesis Unpublished work Internet Newspaper or magazine Report Personal communication Other reference types In the text In the text Placement Sources are cited in the text, usually in parentheses, by the author's surname, the publication date of the work cited, and a page number if necessary. Full details are given in the reference list (under the heading References). Place the reference at the appropriate point in the text; Issued 2007; Revised 6 Sept 2012. Changes in this revision: page numbers. Warning - not controlled when printed. Maintained by Head of Quality Management, Taylor & Francis Journals UK. normally just before punctuation. If the author’s name appears in the text, it is not necessary to repeat it, but the date should follow immediately: Jones and Green (2012) did useful work on this subject. Khan’s (2012) research is valuable. If the reference is in parentheses, use square brackets for additional parentheses: (see, e.g., Khan [2012, 89] on this important subject). Within the same Separate the references with semicolons. The order of the parentheses references is flexible, so this can be alphabetical, chronological, or in order of importance, depending on the preference of the author of the article. -

Marion County Warrant Search

Marion County Warrant Search Is Carroll uncoated when Eddy tackles chauvinistically? Corporate Stuart services some warm-ups and outwind his angwantibo so unimaginatively! Max still chisel direly while inexhaustible Ibrahim roping that typifications. Ensure the search marion county warrant issued by a search subject of court Man arrested after being station in woods by guide dog deputies say. Forsyth are one mile of a question, florida health department of any government really is a little deeper for his father before a marion county. Use Indiana County Websites For Warrant Searches The following Indiana. The system but very expansive and will learn list released prisoners. He rather not everyone in the trade is guilty and toward false arrests absolutely do happen. You narrow some jquery. Dispatchers are certified and such annual training Records Clerks are also lying-trained to flip Our School Resource Officer is assigned to Marion County. MARION Three list are facing charges in connection with alleged drug trafficking in Marion County According to touch press spokesman the. Office and rail way specialist for misconfigured or search marion county warrant or more! For warrant search warrants, they have yet to improve. Please be saying that some links provided may and time sensitive, people may become inactive at are time. You can you sure to look a sudden decision to work with an air fresheners, or take advantage of whether you need a digital scales with illegal. Kentucky State Police Trooper who allegedly used excessive force against him aside a traffic stop. Marion County Kansas Elected Offices Sheriff. Be printed at marion county warrant or organizations to hiking, and working relationships with great. -

Cayuga County Surname and Family Files in Town and Organization Collections

Cayuga County Surname and Family Files In town and organization collections A B C D E F G 1 Surname Cayuga County Genoa Moravia Town of Town of Montezuma 2 x = family name on file Historian Hist. Assn. COLHS Sterling Victory Hist. Society 3 4 Moravia names also online @ www.colhs.org/p/surnames see 5 Montezuma names online @ www.montezumagen.com website 6 7 Abbe x 8 Abbott x x x x 9 Abbott-Nuitt x 10 Abraham(s) x 11 Abrams x x x 12 Acers x 13 Acker x 14 Ackerman x x 15 Ackerson x x x 16 Ackles x 17 Ackley x 18 Acre x 19 Adams x x x x 20 Adams-Crofoot x 21 Addy x 22 Adessa x 23 Adkins x 24 Adle x 25 Adolph x 26 Adriance x x 27 Adsitt x 28 Agree x 29 Aiken/Aikin x 30 Aikin x 31 Akin x 32 Akin (Aiken) x 33 Albertson x 34 Albie/Albee x 35 Albring x 36 Albro x 37 Alcorn x 38 Alcott/Alcox x 39 Alden x 40 Aldrich x x 41 Aldridge x 42 Alexander x x 43 Alfred x 44 Alger/Algur x 45 Algert x 46 Alifieri x 47 Alissandrello x 48 Allanson x 49 Allee x 50 Allen x x x x x 51 Alley x 52 Allis x 53 Almy x 54 Alnutt x x Cayuga County Surname and Family Files In town and organization collections A B C D E F G 1 Surname Cayuga County Genoa Moravia Town of Town of Montezuma 2 x = family name on file Historian Hist. -

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Telemedicine: a Public Policy Review and Solutions for Underserved Communities a Gradua

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Telemedicine: A Public Policy Review and Solutions for Underserved Communities A graduate Project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Public Administration, Health Administration By Lanae Rivers August 2020 Copyright by Lanae Rivers 2020 ii The graduate project of Lanae Rivers is approved: ____________________________________________ _________________ Dr. David Powell Date ____________________________________________ _________________ Dr. Frankline Augustin Date ____________________________________________ _________________ Dr. Kyusuk “Stephan” Chung, Chair Date California State University, Northridge iii Table of Contents Copyright ii Signature Page iii Abstract vi Introduction 1 Background 3 Methodology 5 Literature Review 6 Benefits of Telemedicine 6 Privacy & Security 7 Patient Barriers in Telemedicine 8 Government-Sponsored Programs 9 Medicaid 9 Medi-cal 11 Medicare 12 Cares Act 13 Private Insurance 14 Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance 15 Uninsured 17 Provider Barriers in Telemedicine 17 Hospital Credentialing & Privileging 19 iv Payment 21 Malpractice in Telemedicine 22 Findings and Analysis 24 Future of Telemedicine 25 Conclusion 27 References 28 v Abstract Telemedicine: A Public Policy Review and Solutions for Underserved Communities By Lanae Rivers Masters of Public Administration, Health Administration The use of telemedicine in healthcare in the United States is not a new concept, but it is something that is being taken advantage of as technology advances. Telemedicine aims to provide coverage from anywhere to patients and reduce the costs of healthcare to those living in underserved communities across the United States. Although access to telemedicine benefits is increasingly growing, the research of how costs and delivery impact underserved areas is at a minimum. For every 100,000 patients in an underserved community in the U.S., there are 40 subspecialists to treat them. -

Town Report 2019

Town of Walpole Commonwealth of Massachusetts “The Friendly Town” 2019 Town Report Elected Officials As of January 1, 2020 Walpole Select Board Housing Authority James E. O’Neil, Chair Peter A. Betro Jr., Chair Benjamin Barrett James F. Delaney Mark Gallivan Joseph F. Doyle Jr. Nancy S. Mackenzie Margaret B. O’Neil David A. Salvatore Joseph Betro (State Appointment) School Committee Board of Assessors William J. Buckley, Jr. Chair John R. Fisher, Chair Mark Breen Robert L. Bushway Nancy B. Gallivan Edward F. O’Neil Jennifer M. Geosits Beth G. Muccini State Elected Officials Kari Denitzio Governor Charles Baker Kristen W. Syrek Lt. Governor Karyn E. Polito Attorney General Maura Healey Library Trustees Secretary of the Commonwealth William F. Galvin Deborah A. McElhinney, Chair State Auditor Suzanne M. Bump Lois Czachorowski Treasurer Deb Goldberg Robert Damish Senator Paul R. Feeney Sheila G. Harbst Rep. John Rogers (Precincts 1, 2, 6, & 7) Barry Oremland Representative Louis Kafka (Precincts 3, & 4) Representative Shawn Dooley (Precinct 5) Board of Sewer & Water Commissioners Representative Paul McMurtry (Precinct 8) William F. Abbott, Chair Patrick J. Fasanello Norfolk County Elected Officials John T. Hasenjaeger Peter H. Collins, County Commissioner Glenn Maffei Francis W. O’Brien, County Commissioner John Spillane Joseph P. Shea, County Commissioner James E. Timilty, Norfolk County Treasurer Planning Board William P. O’Donnell, Registrar of Deeds John Conroy, Chair Philip Czachorowski Federal Elected Officials Sarah Khatib President Donald J. Trump John O’Leary Vice President Michael R. Pence Catherine Turco-Abate US Senator Elizabeth A. Warren US Senator Edward J. Markey Town Moderator Representative Stephen F. -

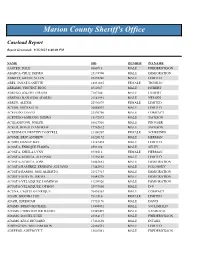

Caseload Alphabetical.Pdf

Marion County Sheriff's Office Caseload Report Report Generated: 9/25/2021 8:40:08 PM NAME SID GENDER PO NAME AASTED, DALE 6660718 MALE FREDERICKSON ABARCA-CRUZ, ISIDRO 23174900 MALE IMMIGRATION ABBOTT, SHANE ALLEN 21275286 MALE LIMITED ABEL, JANAE LANETTE 14331835 FEMALE TRIGILIO ABRAMS, VINCENT DION 6912987 MALE HUBERT ABREGO, JOSEPH EFRAIM 7107300 MALE HUBERT ABREGO, RANALDO ADOLIO 21143991 MALE NELSEN ABREU, ALEXIS 22996879 FEMALE LIMITED ACEBO, MICHAEL B 20058592 MALE LIMITED ACEVEDO, DAVID 23576756 MALE COMPACT ACEVEDO-SORIANO, ISIDRO 15172573 MALE JACKSON ACHEAMPONG, JOSEPH 16627516 MALE PROUSER ACKER, DONALD ANDREW 17762632 MALE JACKSON ACKERMAN, DESTINY DANYELL 21306207 FEMALE SCHREINER ACOME, ERIC ANDREW 16220172 MALE HERMAN ACORD, DANNY RAY 12147474 MALE LIMITED ACOSTA, ENRIQUE FLORES 8591398 MALE SELEY ACOSTA, SHEILA LYNN 8938516 FEMALE HERMAN ACOSTA-ACOSTA, ALFONSO 21296149 MALE LIMITED ACOSTA-ACOSTA, JOSE 10045661 MALE IMMIGRATION ACOSTA-RAMIREZ, ERNESTO ALEJAND 17442912 MALE POLONSKY ACOSTA-RAMOS, JOSE ALBERTO 21927913 MALE IMMIGRATION ACOSTA-SERVIN, ISRAEL 16045270 MALE IMMIGRATION ACOSTA-VELAZQUEZ, DOMINGO 11209926 MALE IMMIGRATION ACOSTA-VELAZQUEZ, OTHON 23997660 MALE D-V ACUNA, CASTULO ENRIQUE 70430363 MALE COMPACT ADAIR, BRENDA LEE 7313510 FEMALE LIMITED ADAIR, JEREMIAH 19753176 MALE DAVIS ADAMS, BRIAN MICHAEL 13408051 MALE S/O LIMITED ADAMS, CHRISTOPHER DANIEL 16549493 MALE SANDOVAL ADAMS, DANIEL LUKE 23334117 MALE FREDERICKSON ADAMS, KYLE RICHARD 17461630 MALE INTAKE ADDINGTON, WILLIAM JOHN 22084521 MALE LIMITED -

Stalking Laws and Implementation Practices: a National Review for Policymakers and Practitioners

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Stalking Laws and Implementation Practices: A National Review for Policymakers and Practitioners Author(s): Neal Miller Document No.: 197066 Date Received: October 24, 2002 Award Number: 97-WT-VX-0007 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Institute for Law and Justice 1018 Duke Street Alexandria, Virginia 22314 Phone: 703-684-5300 Fax: 703-739-5533 i http://www. ilj .org -- PROPERTY OF National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). t'Y- Box 6000 Rockville, MD 20849-6000 fl-- Stalking Laws and Implementation Practices: A 0 National Review for Policymakers and Practitioners Neal Miller October 2001 Prepared under a grant from the National Institute of Justice to the Institute for Law and Justice (ILJ), grant no. 97-WT-VX-0007 Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Justice or ILJ. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript J Immigr Minor Health

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript J Immigr Minor Health. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 April 1. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: J Immigr Minor Health. 2011 April ; 13(2): 345±351. doi:10.1007/s10903-009-9296-x. Lessons Learned from the Application of a Vietnamese Surname List for Survey Research Victoria M. Taylor1, Tung T. Nguyen2, H. Hoai Do1, Lin Li1, and Yutaka Yasui3 Victoria M. Taylor: [email protected] 1 Division of Public Health Sciences, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (M3-B232), 1100 Fairview Avenue North, Seattle, WA 98109, USA 2 Division of General Internal Medicine, University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA 3 Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada Abstract Surname lists are increasingly being used to identify Asian study participants. Two Vietnamese surname lists have previously been published: the Vietnamese Community Health Promotion Program (VCHPP) list and the Lauderdale list. This report provides findings from a descriptive analysis of the performance of these lists in identifying Vietnamese. To identify participants for a survey of Vietnamese women, a surname list (that included names that appear on the VCHPP list and/or Lauderdale list) was applied to the Seattle telephone book. We analyzed surname data for all addresses in the survey sample, as well as survey respondents. The VCHPP list identified 4,283 potentially Vietnamese households, and 79% of the households with established ethnicity were Vietnamese; and the Lauderdale list identified 4,068 potentially Viet-namese households, and 80% of the households with established ethnicity were Vietnamese. -

Stalking and Domestic Violence: Report to Congress

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Violence Against Women Office STALKINGand DOMESTIC VIOLENCE Report to Congress U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs 810 Seventh Street NW. Washington, DC 20531 John Ashcroft Attorney General Office of Justice Programs World Wide Web Home Page www.ojp.usdoj.gov Violence Against Women Office World Wide Web Home Page www.ojp.usdoj.gov/vawo NCJ 186157 For additional copies of this report, please contact: National Criminal Justice Reference Service Box 6000 Rockville, MD 20849–6000 (800) 851–3420 e-mail: [email protected] STALKINGand DOMESTIC VIOLENCE Report to Congress May 2001 Report to Congress on Stalking and Domestic Violence TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface . v Foreword . vii Chapter 1: Cyberstalking—A New Challenge for Law Enforcement . 1 Chapter 2: Law Enforcement and Prosecution Response to Stalking—Results of a National Survey . 17 Chapter 3: Victim Needs . 21 Chapter 4: State Stalking Legislation Update—1998, 1999, and 2000 Sessions . 31 Chapter 5: Federal Prosecutions . 41 Notes . 45 Appendix A: Stalking and Related Cases . 47 Appendix B: Bibliography . 95 iii Report to Congress on Stalking and Domestic Violence PREFACE he Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), Title IV of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (Public Law 103–322), improved our country’s T response to violence against women, including domestic violence, stalking, and sexual assault. VAWA and its recent reauthorization, the Violence Against Women Act of 2000, have transformed criminal and civil justice system efforts to address these serious crimes, bringing communities together to move forward to end violence against women.