1865 Cornwall Quarter Sessions & Assizes Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

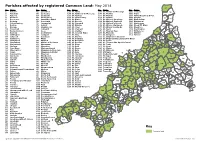

Parish Boundaries

Parishes affected by registered Common Land: May 2014 94 No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name 1 Advent 65 Lansall os 129 St. Allen 169 St. Martin-in-Meneage 201 Trewen 54 2 A ltarnun 66 Lanteglos 130 St. Anthony-in-Meneage 170 St. Mellion 202 Truro 3 Antony 67 Launce lls 131 St. Austell 171 St. Merryn 203 Tywardreath and Par 4 Blisland 68 Launceston 132 St. Austell Bay 172 St. Mewan 204 Veryan 11 67 5 Boconnoc 69 Lawhitton Rural 133 St. Blaise 173 St. M ichael Caerhays 205 Wadebridge 6 Bodmi n 70 Lesnewth 134 St. Breock 174 St. Michael Penkevil 206 Warbstow 7 Botusfleming 71 Lewannick 135 St. Breward 175 St. Michael's Mount 207 Warleggan 84 8 Boyton 72 Lezant 136 St. Buryan 176 St. Minver Highlands 208 Week St. Mary 9 Breage 73 Linkinhorne 137 St. C leer 177 St. Minver Lowlands 209 Wendron 115 10 Broadoak 74 Liskeard 138 St. Clement 178 St. Neot 210 Werrington 211 208 100 11 Bude-Stratton 75 Looe 139 St. Clether 179 St. Newlyn East 211 Whitstone 151 12 Budock 76 Lostwithiel 140 St. Columb Major 180 St. Pinnock 212 Withiel 51 13 Callington 77 Ludgvan 141 St. Day 181 St. Sampson 213 Zennor 14 Ca lstock 78 Luxul yan 142 St. Dennis 182 St. Stephen-in-Brannel 160 101 8 206 99 15 Camborne 79 Mabe 143 St. Dominic 183 St. Stephens By Launceston Rural 70 196 16 Camel ford 80 Madron 144 St. Endellion 184 St. Teath 199 210 197 198 17 Card inham 81 Maker-wi th-Rame 145 St. -

Wind Turbines East Cornwall

Eastern operational turbines Planning ref. no. Description Capacity (KW) Scale Postcode PA12/02907 St Breock Wind Farm, Wadebridge (5 X 2.5MW) 12500 Large PL27 6EX E1/2008/00638 Dell Farm, Delabole (4 X 2.25MW) 9000 Large PL33 9BZ E1/90/2595 Cold Northcott Farm, St Clether (23 x 280kw) 6600 Large PL15 8PR E1/98/1286 Bears Down (9 x 600 kw) (see also Central) 5400 Large PL27 7TA E1/2004/02831 Crimp, Morwenstow (3 x 1.3 MW) 3900 Large EX23 9PB E2/08/00329/FUL Redland Higher Down, Pensilva, Liskeard 1300 Large PL14 5RG E1/2008/01702 Land NNE of Otterham Down Farm, Marshgate, Camelford 800 Large PL32 9SW PA12/05289 Ivleaf Farm, Ivyleaf Hill, Bude 660 Large EX23 9LD PA13/08865 Land east of Dilland Farm, Whitstone 500 Industrial EX22 6TD PA12/11125 Bennacott Farm, Boyton, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 8NR PA12/02928 Menwenicke Barton, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 8PF PA12/01671 Storm, Pennygillam Industrial Estate, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 7ED PA12/12067 Land east of Hurdon Road, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 9DA PA13/03342 Trethorne Leisure Park, Kennards House 500 Industrial PL15 8QE PA12/09666 Land south of Papillion, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 7EZ PA12/00649 Trevozah Cross, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 9LT PA13/03604 Land north of Treguddick Farm, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 7JN PA13/07962 Land northwest of Bottonett Farm, Trebullett, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 9QF PA12/09171 Blackaton, Lewannick, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 7QS PA12/04542 Oak House, Trethawle, Horningtops, Liskeard 500 Industrial -

Truro 1961 Repairs BLISLAND St

Locality Church Name Parish County Diocese Date Grant reason BALDHU St. Michael & All Angels BALDHU Cornwall Truro 1961 Repairs BLISLAND St. Pratt BLISLAND Cornwall Truro 1894-1895 Reseating/Repairs BOCONNOC Parish Church BOCONNOC Cornwall Truro 1934-1936 Repairs BOSCASTLE St. James MINSTER Cornwall Truro 1899 New Church BRADDOCK St. Mary BRADDOCK Cornwall Truro 1926-1927 Repairs BREA Mission Church CAMBORNE, All Saints, Tuckingmill Cornwall Truro 1888 New Church BROADWOOD-WIDGER Mission Church,Ivyhouse BROADWOOD-WIDGER Devon Truro 1897 New Church BUCKSHEAD Mission Church TRURO, St. Clement Cornwall Truro 1926 Repairs BUDOCK RURAL Mission Church, Glasney BUDOCK RURAL, St. Budoc Cornwall Truro 1908 New Church BUDOCK RURAL St. Budoc BUDOCK RURAL, St. Budoc Cornwall Truro 1954-1955 Repairs CALLINGTON St. Mary the Virgin CALLINGTON Cornwall Truro 1879-1882 Enlargement CAMBORNE St. Meriadoc CAMBORNE, St. Meriadoc Cornwall Truro 1878-1879 Enlargement CAMBORNE Mission Church CAMBORNE, St. Meriadoc Cornwall Truro 1883-1885 New Church CAMELFORD St. Thomas of Canterbury LANTEGLOS BY CAMELFORD Cornwall Truro 1931-1938 New Church CARBIS BAY St. Anta & All Saints CARBIS BAY Cornwall Truro 1965-1969 Enlargement CARDINHAM St. Meubred CARDINHAM Cornwall Truro 1896 Repairs CARDINHAM St. Meubred CARDINHAM Cornwall Truro 1907-1908 Reseating/Repairs CARDINHAM St. Meubred CARDINHAM Cornwall Truro 1943 Repairs CARHARRACK Mission Church GWENNAP Cornwall Truro 1882 New Church CARNMENELLIS Holy Trinity CARNMENELLIS Cornwall Truro 1921 Repairs CHACEWATER St. Paul CHACEWATER Cornwall Truro 1891-1893 Rebuild COLAN St. Colan COLAN Cornwall Truro 1884-1885 Reseating/Repairs CONSTANTINE St. Constantine CONSTANTINE Cornwall Truro 1876-1879 Repairs CORNELLY St. Cornelius CORNELLY Cornwall Truro 1900-1901 Reseating/Repairs CRANTOCK RURAL St. -

![CORNWALL.] FAR 946 ( L,OST OFFICE FARMERB Continued](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3089/cornwall-far-946-l-ost-office-farmerb-continued-403089.webp)

CORNWALL.] FAR 946 ( L,OST OFFICE FARMERB Continued

[CORNWALL.] FAR 946 ( l,OST OFFICE FARMERB continued. Kittow John, Higher Penrest, Lezant, Laity William, Tregartha, St. Hilary, Kempe Jas. Rosemanowas,St.Stythians Launceston Marazion Kempe John, Trolvis, St. Stytbians Kittow Jonathan, St. Clether, Launcstn Laity W.Tregiffian, St.Buryan,Penznce Kempthorne Charles, Carythenack, Kittow R. W estcot, Tremaine, Launcstn Laity W. Trerose, Mawnan, Falmouth Constantine, Penryn Kittow T.Browda,Linkinhorne,Callngtn Lake Daniel, Trevalis, St. Stythians Kempthorne James, Chenhall, Mawnan, Kittow Thomas, Tremaine, Launceston Lamb William & Charles, Butler's Falmouth KittowT. Uphill, Linkinhorne,Callingtn tenement, Lanteglos-by-Fowey,Fowy Kempthorne J. Park, Illogan,Camborne Kittow W. Trusell, Tremaine,Launcestn Lamb Charles, Lower Langdon, St. Kendall Mrs. Edwd. Treworyan, Probus KneeboneC.Polgear,Carnmenellis,Rdrth Neot, Liskeard Kendall J. Honeycombs, St.Allen,Truro Kneebone Joseph, Manuals, St. Columb Lamb H. Tredethy, St. Mabyn, Bodmin Kendall Richard, Zelah, St.Allen,Truro Minor Lamb J .Tencreek, St.Veep, Lostwithiel Kendall Roger, Trevarren, St. Mawgan, KneeboneRichard, Hendra, St. Columb Lambrick J.Lesneage,St.Keverne,Hlstn St. Columb Minor Lambrick John, Roskruge,St.Anthony- Kendall SilasFrancis,Treworyan, Probus Knee bone T. Reginnis,St. Paul,Penzance in-M eneage, Helston Kendall Thoma..'l, Greenwith common, Kneebone Thos. South downs, Redruth Lamerton Wm. Botus Fleming, Hatt Perran-arworthal Kneebone W. Gwavas,St.Paul,Penzance Laming Whitsed, Lelant, Hay le KendallThomas,Trevarren,St.Mawgan, Knight James, Higher Menadue, Lux- Lampshire W.Penglaze, St.Alleu,Truro St. Columb ulyan, Bodmin Lander C. Tomrose, Blisland, Bodmin Kendall 'Villiam, Bodrugan, Gorran Knight J. Rosewarrick,Lanivet,Bodmin Lander C. Skews, St. Wenn, Bodmin Kendall William, Caskean, Probus Knight }Jrs. J .Trelill,St.Kew, Wadebrdg Lander J. -

![CORNWALL.] FAR 952 [POST OFFICE FARMERS Continued](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5174/cornwall-far-952-post-office-farmers-continued-445174.webp)

CORNWALL.] FAR 952 [POST OFFICE FARMERS Continued

[CORNWALL.] FAR 952 [POST OFFICE FARMERS continued. Penna W. Gear, Perranzabuloe, Truro Phillips Jas. Carnhill, Gwinear, Hayle Pearce Voisey, Pillaton, St. Mellion Penny Edward, Butternell, Linkin- PhillipsJas.Raskrow,St.Gluvias,Penryn Pearce W .Calleynough, Helland, Bodmn borne, Callington Phillips J. Bokiddick, Lanivet, Bodmin Pearce W. Helland, Roche, St. Austell Penny Mrs. Luckett, Stoke Clims- Phillips John, Higher Greadow, Lan- Pearce W.Boskell,Treverbyn,St.Austell land, Callington livery, Bodmin Pearce William, Bucklawren, St. Penprage John, Higher Rose vine, Phillips John, Mineral court, St. Martin-by-Looe, Liskeard Gerrans, Grampound Stephens-in-Branwell Pearce Wm. Durfold, Blisland,Bodmin Penrose J. Bojewyan,Pendeen,Penzance Phillips John, N anquidno, St. Just-in- Pearce W. Hobpark, Pelynt, Liskeard Penrose Mrs .•lane, Coombe, Fowey Penwith, Penzance Pearce William, Mesmeer, St. Minver, Penrose J. Goverrow,Gwennap,Redruth Phillips John, Tregurtha, St. Hilary, W adebridge PenroseT .Bags ton, Broadoak ,Lostwi thil M arazion Pearce William,'Praze, St. Erth, Hayle PenroseT. Trevarth, Gwennap,Redruth Phillips John, Trenoweth,l\Iabe,Penryn Pearce William, Roche, St. Austell Percy George, Tutwill, Stoke Clims- Phillips John, Treworval, Constantine, Pearce Wm. Trelask~ Pelynt, Liskeard land, Callington Penryn Pearn John, Pendruffie, Herods Foot, PercyJames, Tutwill, Stoke Climsland, Phillips John, jun. Bosvathick, Con- Liskeard Callington stantine, Penryn Peam John, St. John's, Devonport Percy John, Trehill, Stoke Climsland, Phillips Mrs. Mary, Greadow, Lan- Pearn Robt. Penhale, Duloe, Liskeard Callington livery, Bodmin Pearn S.Penpont, Altemun, Launcestn Percy Thomas, Bittams, Calstock Phillips Mrs. Mary, Penventon,Illogan, Peam T.Trebant, Alternun, Launceston Perkin Mrs. Mary, Haydah, Week St. Redruth PearseE.Exevill,Linkinhorne,Callingtn Mary, Stratton Pl1illips M. -

![CORNWALL.] Farmers-Continued](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4222/cornwall-farmers-continued-484222.webp)

CORNWALL.] Farmers-Continued

TRADES DIRECTORY.] 941 FAR [CORNWALL.] FARMERs-continued. Gummow William,Pettimee,St,.l\linver, Harper John, Tall Petherwin, Soutll Gould Edward, Merrymeeting, Gwen- 'Vadebridge Petherwin, Launceston nap, Redrutb Gundry Mrs. John & Son, Trebah, Con- HarperSaml. Mawla,St. Agnes, Scorrier Govett James, Halbathick, Liskeard stantine, Pemyn Harris P.&H.Bilberry,Roche,St.Austell Goyne J. Goonvrea, St. Agnes, Scorrier Gundry Benj. Perran-uthnoe, Marazion Harri~A. Trelugga,RuanMajor,Helston Goyns Samuel, W'ringworthy, Morval, Gundry B.jun.Perran-uthnoe,Marazior. Harris A.R.Tregenna,Biisland, Bodmin Liskeard Gundry Miss Elizabeth, Goldsithney, HaiTis Chr. Highway, Illogan, Redruth Gray Mrs. Catherine, Twelveheads, Perran-nthnoe, Marazion Harris Chr. Treg-oose, Sithney, Helston Gwennap, Scorrier Gundry Hy.Porkellis, Wendron, Helston Harris Di!rory, Prestacott, Kilkhamp- Greea J. Hellengove, Gulval, Penzance Gundry Rd. Porkellis, W endron, Helston ton, Stratton Green John, St. Feock, Truro Gundry Thos. Bosworgy,St.Et·th, Hayle HarrisE.Botallick,Boconnoc,Lostwitllil GreenMrs.Maria, Westgate st.Launcestn Gunn Hugh, Coombe, Kea, Truro Harris Edward, Frogmore, Lanteglos Green William, Sparrel stick, St. Min- Guy A. Boswarthen, Madron, Penzance by-Fowey, Fowey ver, Wadebridge Guy B. Boswarthen, Madron, Penzance Harris E.Pigscombe,Lanreath,Liskeard GreenawayR.Dimma,Jacobstow,Strattn GuyJonathan,Treswarrow,St.Endellion, Harris Fras. Banns, St. Agnes, Scorrier Greenaway Samuel, Limsworthy, Kilk- Wadebridge Harris George, Antony, Devonport hampton, Stratton Guy Jonathan Samuel, Trewint, St. HarrisG.Nrth.Country,Treleigh,Redrth Greenaway Thomas, Trebarfoot, Pound- EndellioH, Wadebridge Harris H. Gry lis, Lesnewth, Boscastle stock, Strattou Guy Robert Andrew, Trelights, St. HarrisH.Landrine,Ladock,Grmpnd.Rd Greenwood G.Tredwin,Davidstw.Eoscstl Endellion, Wadebridge HarrisH.Trengune,,Varbstow,Launcstn Greenwood J ames, Tregurren, Mawgan- Gwenap J. -

Offers Over £405,000

Catchfrench Barn, Trerulefoot, Saltash, Cornwall, PL12 5BY Ref: 85753 Torpoint 10 miles, Plymouth 15 miles (all distances approximate) Presenting this lovely four bedroomed Period Barn Conversion beautifully located in a very private location and boarded on three sides by the grounds of Catchfrench Manor. Oak framed triple Garage (built by English Heritage) with 27ft triple aspect Studio/Office above. Private gated driveway with room for numerous cars. Sitting room with wood burner, Dining room, Kitchen, Breakfast room, Conservatory and Utility room. Double glazing and central heating. EPC Rating D. Offers Over £405,00 0 Catchfrench Barn, Trerulefoot, Saltash, Cornwall, PL12 5BY The property is situated near Trerulefoot which is located approximately 4 miles from Master Bedroom. the market town of Liskeard, conveniently placed with good access to the A38 dual carriageway. Liskeard provides a wide range of shops and other amenities including BATHROOM supermarkets and out of town retail outlets, indoor sports complex and educational uPVC double glazed window to front aspect, three piece modern white suite comprising fantastic oversize pedestal wash hand basin, low-level WC, matching contemporary bath facilities, doctors, community hospital and places of worship. The village of Tideford with a lively country pub and old fashioned butcher is 3 miles distant and historic St (Hansgrove fittings) with centrally located taps and overflow to allow room for two. Germans with post office, convenience store, pub and annual literature, ar ts and music Electric shower. Chrome towel ladder radiator. Wood effect floor. Inset spotlights to festival 4 miles. Saltash and the Tamar Bridge are approximately 5 miles to the east. -

Trio 1989-05

ELECTION RESULTS THANK YOU The results of the District Council Evelyn 4 Olive Dunford wish to election are: thank all the people of Port Isaac, Harvey Lander 762 (Majority 193) and St. Endelllon, who showed such Henry Symons 569 wonderful love and kindness during Fred Hocking 490 Olive's recent illness. We are sure Jennifer Green 151 that the editor will not allow us the space to thank everybody who helped in so many ways - the drivers who took Evelyn to Truro every day; CONCERTS AT ST. ENOELLION the cooks who fed him, the ladies Friday 16th. June, 7.30pm: 'Sports who did the washing and shopping - COMMUNITY NEWSLETTER and Pastimes'. The life of the not to mention the hundreds of "Get composer Erik Satie, presented by Issued eleven times a year for the Well" cards and the bouquets of civil parish of St. Endellion, North Bob Devereux and Paul Hancock flowers which filled the Coronary Cornwall. Available at lOp. per copy (Piano). Paul Hancock who lives at Care Unit at Treliske where we from The Harbour Shop and The Bay Hayle is himself a composer, and celebrated our 36th. Wedding Gift Shop, Port Isaac, and the Post Office Stores, Trelights, or by mail being a Cornishman has written Anniversary! Thank you one and all! music depicting parts of the County. for a yearly subscription of £3.30. Admission £2.50. We are pleased to say that the Published by Robin Penna (who does Bionic Woman is doing well with her Friday 30th. June, 7.30pm: Bristol not necessarily hold the same views Pacemaker. -

Environmental Protection Final Draft Report

Environmental Protection Final Draft Report ANNUAL CLASSIFICATION OF RIVER WATER QUALITY 1992: NUMBERS OF SAMPLES EXCEEDING THE QUALITY STANDARD June 1993 FWS/93/012 Author: R J Broome Freshwater Scientist NRA C.V.M. Davies National Rivers Authority Environmental Protection Manager South West R egion ANNUAL CLASSIFICATION OF RIVER WATER QUALITY 1992: NUMBERS OF SAMPLES EXCEEDING TOE QUALITY STANDARD - FWS/93/012 This report shows the number of samples taken and the frequency with which individual determinand values failed to comply with National Water Council river classification standards, at routinely monitored river sites during the 1992 classification period. Compliance was assessed at all sites against the quality criterion for each determinand relevant to the River Water Quality Objective (RQO) of that site. The criterion are shown in Table 1. A dashed line in the schedule indicates no samples failed to comply. This report should be read in conjunction with Water Quality Technical note FWS/93/005, entitled: River Water Quality 1991, Classification by Determinand? where for each site the classification for each individual determinand is given, together with relevant statistics. The results are grouped in catchments for easy reference, commencing with the most south easterly catchments in the region and progressing sequentially around the coast to the most north easterly catchment. ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 110221i i i H i m NATIONAL RIVERS AUTHORITY - 80UTH WEST REGION 1992 RIVER WATER QUALITY CLASSIFICATION NUMBER OF SAMPLES (N) AND NUMBER -

Cornwall Council Altarnun Parish Council

CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Baker-Pannell Lisa Olwen Sun Briar Treween Altarnun Launceston PL15 7RD Bloomfield Chris Ipc Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SA Branch Debra Ann 3 Penpont View Fivelanes Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY Dowler Craig Nicholas Rivendale Altarnun Launceston PL15 7SA Hoskin Tom The Bungalow Trewint Marsh Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TF Jasper Ronald Neil Kernyk Park Car Mechanic Tredaule Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RW KATE KENNALLY Dated: Wednesday, 05 April, 2017 RETURNING OFFICER Printed and Published by the RETURNING OFFICER, CORNWALL COUNCIL, COUNCIL OFFICES, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Kendall Jason John Harrowbridge Hill Farm Commonmoor Liskeard PL14 6SD May Rosalyn 39 Penpont View Labour Party Five Lanes Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY McCallum Marion St Nonna's View St Nonna's Close Altarnun PL15 7RT Richards Catherine Mary Penpont House Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SJ Smith Wes Laskeys Caravan Farmer Trewint Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TG The persons opposite whose names no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. -

CORN"T ALL. [KELLY's

1404 FAR CORN"T ALL. [KELLY's FARMERS continued. Phillips W.Rosenea,Lanliverr,Lostwithl Pomery John, Trethem & Pnlpry, St. Peters John, Kelhelland, Camborne Phillips William John, Bokiddick, Jnst-in-Roseland, Falmonth Peters John, Velandrucia, St. Stythians, Lamvet, Bodmin Pomroy J. Bearland, Callington R.S.O Perranwell Station R.S.O Phillips William John, Lawhibbet, St. Pomroy James, West Redmoor, South Peters John, Windsor Stoke, Stoke Sampsons, Par Station R.S.O hill, Callington R.S.O Climsland, Callington R.S.O Phillips William John, Tregonning, Po:ntingG.Come to Good,PenanwellRSO Peters John, jun. Nancemellan, Kehel- Luxulyan, Lostwithiel Pool John, Penponds, Cam borne land, Camborne Philp Mrs. Amelia, Park Erissey, 'fre- Pooley Henry, Carnhell green, Gwinear, Peters Richard, Lannarth, Redruth leigh, Redruth Camborne Peters S. Gilly vale, Gwennap, Redruth PhilpJn.Belatherick,St.Breward,Bodmin Pooley James,Mount Wise,Carnmenellis, Peters Thomas, Lannarth, Redruth PhilpJ. Colkerrow, Lanlivery ,Lostwithiel Redruth Peters T.J.FourLanes,Loscombe,Redrth Philp J.Harrowbarrow,St.Mellion R.S.O Pooley Wm. Penstraze, Kenwyn, Truro Peters T.Shallow adit, Treleigh,Redruth Philp John, Yolland, Linkinhorne, Cal- Pore Jas. Trescowe, Godolphin, Helston Peters William, Trew1then,St. Stythians, lington R.S.O Pope J. Trescowe, Godolphin, Helston Perranwell Station R.S.O Philp John, jun. Cardwain & Cartowl, Pope Jsph. Trenadrass, St. Erth, Hayle Petherick Thomas, Pempethey, Lante- Pelynt, Duloe R.S.O Pope R. Karly, Jacobstow,StrattonR.S.O glos, Carre1ford Philp Leonard, Downhouse, Stoke Pope William, Lambourne, Perran- Petherick Thomas, Treknow mills, Tin- Climsland, Callingto• R.S.O Zabuloe, Perran-Porth R.S.O tagel, Camelford PhilpRd.CarKeen,St.Teath,Camelford Porter Wm. -

CORNWALL Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph CORNWALL Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No Parish Location Position CW_BFST16 SS 26245 16619 A39 MORWENSTOW Woolley, just S of Bradworthy turn low down on verge between two turns of staggered crossroads CW_BFST17 SS 25545 15308 A39 MORWENSTOW Crimp just S of staggered crossroads, against a low Cornish hedge CW_BFST18 SS 25687 13762 A39 KILKHAMPTON N of Stursdon Cross set back against Cornish hedge CW_BFST19 SS 26016 12222 A39 KILKHAMPTON Taylors Cross, N of Kilkhampton in lay-by in front of bungalow CW_BFST20 SS 25072 10944 A39 KILKHAMPTON just S of 30mph sign in bank, in front of modern house CW_BFST21 SS 24287 09609 A39 KILKHAMPTON Barnacott, lay-by (the old road) leaning to left at 45 degrees CW_BFST22 SS 23641 08203 UC road STRATTON Bush, cutting on old road over Hunthill set into bank on climb CW_BLBM02 SX 10301 70462 A30 CARDINHAM Cardinham Downs, Blisland jct, eastbound carriageway on the verge CW_BMBL02 SX 09143 69785 UC road HELLAND Racecourse Downs, S of Norton Cottage drive on opp side on bank CW_BMBL03 SX 08838 71505 UC road HELLAND Coldrenick, on bank in front of ditch difficult to read, no paint CW_BMBL04 SX 08963 72960 UC road BLISLAND opp. Tresarrett hamlet sign against bank. Covered in ivy (2003) CW_BMCM03 SX 04657 70474 B3266 EGLOSHAYLE 100m N of Higher Lodge on bend, in bank CW_BMCM04 SX 05520 71655 B3266 ST MABYN Hellandbridge turning on the verge by sign CW_BMCM06 SX 06595 74538 B3266 ST TUDY 210 m SW of Bravery on the verge CW_BMCM06b SX 06478 74707 UC road ST TUDY Tresquare, 220m W of Bravery, on climb, S of bend and T junction on the verge CW_BMCM07 SX 0727 7592 B3266 ST TUDY on crossroads near Tregooden; 400m NE of Tregooden opp.