Go and Cognition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUNE 1950 EVERY SECOND MONTH T BIR.THDAY WEEK.END TOURNA^Rtents T SOUTHSEA TOURNEY T Overseos & N.Z

rTE ]IEW ZEALAII[I Vol. 3-No. 14 JUNE 1950 EVERY SECOND MONTH t BIR.THDAY WEEK.END TOURNA^rtENTS t SOUTHSEA TOURNEY t Overseos & N.Z. Gomes ,1 ts t PROBLEMS + TH E SLAV DEFENCE :-, - t lr-;ifliir -rr.]t l TWO SH ILLIN GS "Jl 3 OIIDSSPLAYBBSe LIBBABY 3 ,,C BOOKS BOOKS H E INTER SOLD BY Fol rvhich tir THE NEW ZEATAND CHESSPLAYER ANNUAL 256 DOMTNION ROAD, LIFI AUCKLAND. PHONE 64-277 (Ne In ordering, merely quote Editor and I catalogue number shown. Postage: Add one penny in every Z/- Champion anr Australia. GAMES G l3-Fifty Great Games of Modern Chess- Golombek. G l-My Best Well annotated. and very gc - _ What son' Games, 1924-32-Alekhine. 120 value. 4/3 games by the greatest player and the greatest annotator. 14/- G l4-Moscow - Prague Match, lg46-The -_ " I take games of exceptional interest Revierv.' Your G 2-Capablanca's Hundred Best Games- to all advanc._ Forest Hills. l p_lay_ery (not recommended beginners Golombek. A book grace for " I have lea, to everv- chess WeII indexed for openings ; and endings. 3/- ancl Purdy's r player's _ library. Well-selected games extensively G l5-Amenities and Background all the other l annotated. 17/G of Che=. bought."-H.A Play-Napier. Delightful liiile book of gre=. G 3-Tarrasch's Best Games-Reinfeld. 1BB " One maga fully annotated games based on Tarrasch,s g_a1es by a master of Chess and writing. 3/- -'eaches chess' own notes. 23/- G 16-Great Britain v. -

Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames

Games of No Chance MSRI Publications Volume 29, 1996 Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames LEWIS STILLER Abstract. This article has three chief aims: (1) To show the wide utility of multilinear algebraic formalism for high-performance computing. (2) To describe an application of this formalism in the analysis of chess endgames, and results obtained thereby that would have been impossible to compute using earlier techniques, including a win requiring a record 243 moves. (3) To contribute to the study of the history of chess endgames, by focusing on the work of Friedrich Amelung (in particular his apparently lost analysis of certain six-piece endgames) and that of Theodor Molien, one of the founders of modern group representation theory and the first person to have systematically numerically analyzed a pawnless endgame. 1. Introduction Parallel and vector architectures can achieve high peak bandwidth, but it can be difficult for the programmer to design algorithms that exploit this bandwidth efficiently. Application performance can depend heavily on unique architecture features that complicate the design of portable code [Szymanski et al. 1994; Stone 1993]. The work reported here is part of a project to explore the extent to which the techniques of multilinear algebra can be used to simplify the design of high- performance parallel and vector algorithms [Johnson et al. 1991]. The approach is this: Define a set of fixed, structured matrices that encode architectural primitives • of the machine, in the sense that left-multiplication of a vector by this matrix is efficient on the target architecture. Formulate the application problem as a matrix multiplication. -

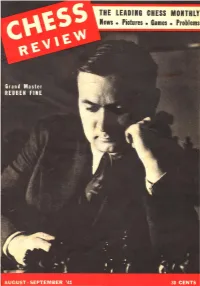

THE LEADING CHESS MOIITHLY News

THE LEADING CHESS MOIITHLY News. Pictures. Games. Problems • Learn winning technique from Rubinstein's brilliant games you CAN GET more practical information on how to play winning chess by study Rubinstein (Black) Won ing the games of the great RUBINSTEIN than in Four Crushing Moves! you could obtain from a dozen theoretical text-books. 1 ... RxKtl! By playing over the selections in "Rubin stein's Chess Masterpieces," you will see for 2 PxQ yourself how this great strategist developed R.Q7!! his game with accuracy and precision, over 3 QxR came his world-renowned opponents with BxBch crushing blows in the middle-game or with superb, polished technique in the end-game, 4 Q-Kt2 There is no beller or more pleasant way of R·HS!! inproving your knowledge of chess. You will 5 Resigns enjoy these games for their entertainment value alone. You will learn how to apply the This startling combination from Ru underlying principles of Rubinstein's winning binstein's "Immortal Game" reveals technique to your own games. Complete and his great genius and shows how the thorough annotations explain the intricacies Grandmaster used "blitz-krieg" tac of Rubinstein's play, help you to understand tics when given the opportunity. the motives and objectives. CREATIVE GENIUS REVEALED IN GAMES See Page 23 of this new book con Rubinstein has added more to chess theory taining 100 of Rubinstein's brilliant. and technique than any other master in the instructive games. Just published. past 30 years! His creative genius is revealed Get your copy NOW. in this book. -

THE PSYCHOLOGY of CHESS: an Interview with Author Fernand Gobet

FM MIKE KLEIN, the Chess Journalists Chess Life of America's (CJA) 2017 Chess Journalist of the Year, stepped OCTOBER to the other side of the camera for this month's cover shoot. COLUMNS For a list of all CJA CHESS TO ENJOY / ENTERTAINMENT 12 award winners, It Takes A Second please visit By GM Andy Soltis chessjournalism.org. 14 BACK TO BASICS / READER ANNOTATIONS The Spirits of Nimzo and Saemisch By GM Lev Alburt 16 IN THE ARENA / PLAYER OF THE MONTH Slugfest at the U.S. Juniors By GM Robert Hess 18 LOOKS AT BOOKS / SHOULD I BUY IT? Training Games By John Hartmann 46 SOLITAIRE CHESS / INSTRUCTION Go Bogo! By Bruce Pandolfini 48 THE PRACTICAL ENDGAME / INSTRUCTION How to Write an Endgame Thriller By GM Daniel Naroditsky DEPARTMENTS 5 OCTOBER PREVIEW / THIS MONTH IN CHESS LIFE AND US CHESS NEWS 20 GRAND PRIX EVENT / WORLD OPEN 6 COUNTERPLAY / READERS RESPOND Luck and Skill at the World Open BY JAMAAL ABDUL-ALIM 7 US CHESS AFFAIRS / GM Illia Nyzhnyk wins clear first at the 2018 World Open after a NEWS FOR OUR MEMBERS lucky break in the penultimate round. 8 FIRST MOVES / CHESS NEWS FROM AROUND THE U.S. 28 COVER STORY / ATTACKING CHESS 9 FACES ACROSS THE BOARD / How Practical Attacking Chess is Really Conducted BY AL LAWRENCE BY IM ERIK KISLIK 51 TOURNAMENT LIFE / OCTOBER The “secret sauce” to good attacking play isn’t what you think it is. 71 CLASSIFIEDS / OCTOBER CHESS PSYCHOLOGY / GOBET SOLUTIONS / OCTOBER 32 71 The Psychology of Chess: An Interview with Author 72 MY BEST MOVE / PERSONALITIES Fernand Gobet THIS MONTH: FM NATHAN RESIKA BY DR. -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

Dutchman Who Did Not Drink Beer. He Also Surprised My Wife Nina by Showing up with Flowers at the Lenox Hill Hospital Just Before She Gave Birth to My Son Mitchell

168 The Bobby Fischer I Knew and Other Stories Dutchman who did not drink beer. He also surprised my wife Nina by showing up with flowers at the Lenox Hill Hospital just before she gave birth to my son Mitchell. I hadn't said peep, but he had his quiet ways of finding out. Max was quiet in another way. He never discussed his heroism during the Nazi occupation. Yet not only did he write letters to Alekhine asking the latter to intercede on behalf of the Dutch martyrs, Dr. Gerard Oskam and Salo Landau, he also put his life or at least his liberty on the line for several others. I learned of one instance from Max's friend, Hans Kmoch, the famous in-house annotator at AI Horowitz's Chess Review. Hans was living at the time on Central Park West somewhere in the Eighties. His wife Trudy, a Jew, had constant nightmares about her interrogations and beatings in Holland by the Nazis. Hans had little money, and Trudy spent much of the day in bed screaming. Enter Nina. My wife was working in the New York City welfare system and managed to get them part-time assistance. Hans then confided in me about how Dr. E greased palms and used his in fluence to save Trudy's life by keeping her out of a concentration camp. But mind you, I heard this from Hans, not from Dr. E, who was always Max the mum about his good deeds. Mr. President In 1970, Max Euwe was elected president of FIDE, a position he held until 1978. -

A GUIDE to SCHOLASTIC CHESS (11Th Edition Revised June 26, 2021)

A GUIDE TO SCHOLASTIC CHESS (11th Edition Revised June 26, 2021) PREFACE Dear Administrator, Teacher, or Coach This guide was created to help teachers and scholastic chess organizers who wish to begin, improve, or strengthen their school chess program. It covers how to organize a school chess club, run tournaments, keep interest high, and generate administrative, school district, parental and public support. I would like to thank the United States Chess Federation Club Development Committee, especially former Chairman Randy Siebert, for allowing us to use the framework of The Guide to a Successful Chess Club (1985) as a basis for this book. In addition, I want to thank FIDE Master Tom Brownscombe (NV), National Tournament Director, and the United States Chess Federation (US Chess) for their continuing help in the preparation of this publication. Scholastic chess, under the guidance of US Chess, has greatly expanded and made it possible for the wide distribution of this Guide. I look forward to working with them on many projects in the future. The following scholastic organizers reviewed various editions of this work and made many suggestions, which have been included. Thanks go to Jay Blem (CA), Leo Cotter (CA), Stephan Dann (MA), Bob Fischer (IN), Doug Meux (NM), Andy Nowak (NM), Andrew Smith (CA), Brian Bugbee (NY), WIM Beatriz Marinello (NY), WIM Alexey Root (TX), Ernest Schlich (VA), Tim Just (IL), Karis Bellisario and many others too numerous to mention. Finally, a special thanks to my wife, Susan, who has been patient and understanding. Dewain R. Barber Technical Editor: Tim Just (Author of My Opponent is Eating a Doughnut and Just Law; Editor 5th, 6th and 7th editions of the Official Rules of Chess). -

January 1945

JANUARY 1945 THE IMAGERY OF C HESS (SuP~l t J) 35 CENTS Subscription Rat e 'NE YEAR $3 N O. 35 or No. 36 MO LD E D CHESSMEN S t ude nt Si ze in Display Box These beautiful chess men are made of The c h e~s men pictured belo\\' arc of ;l genuine Terlllite and arc ideal for hOllie Ilse. sl i);hUy 'liffCI'cnt design ;u1(1 are made by All pieces and [lawns arc St;lIl1lton pattern. anothel' manufactm 'cl', They are avai lable Sturdy nlld practical, they Il'ili sland hard only in the StalUJani Size in mottled Ivory usage. and iJ1lld., T hey present a pleasing. mal'hle· like "i!pcal'ancc. NO. 80 ( S lack &. Ivory) or N o. 81 ( Red &. Ivory : Com. plet e set of s tandard s i~ e c hessmen, fe lt ed, in durabl e, two section, c lot h_covered case. K ing height 2%"; base squdiameteares r _1_5/16"__ ______, F__or____ us__e _o____n bo__ ar__ds__ _______w ith _1%"_____ or__ __2" _ $6.95 Standard s ize ches!\ No. 35 ( Black & Iyory) or No. 36 ( Red & IY ory) : Com. set No. 85 Iliet ured plet e set of student size c hessm e n. fe lted, in cardboard box. King height 2%" ; base d ia met e r 1 3/16". For use on above. ThQ Knight boards w it h l Y2" or 1%" sq ua res ___ ____ ____ ___________ _ $3.50 and King of thl!\ ~et are illustratel] at No. -

SDSU Template, Version 11.1

USING CHESS AS A TOOL FOR PROGRESSIVE EDUCATION _______________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of San Diego State University _______________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Sociology _______________ by Haroutun Bursalyan Summer 2016 iii Copyright © 2016 by Haroutun Bursalyan All Rights Reserved iv DEDICATION To my wife, Micki. v We learn by chess the habit of not being discouraged by present bad appearances in the state of our affairs, the habit of hoping for a favorable change, and that of persevering in the search of resources. The game is so full of events, there is such a variety of turns in it, the fortune of it is so subject to sudden vicissitudes, and one so frequently, after long contemplation, discovers the means of extricating one's self from a supposed insurmountable difficulty.... - Benjamin Franklin The Morals of Chess (1799) vi ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Using Chess as a Tool for Progressive Education by Haroutun Bursalyan Master of Arts in Sociology San Diego State University, 2016 This thesis will look at the flaws in the current public education model, and use John Dewey’s progressive education reform theories and the theory of gamification as the framework to explain how and why chess can be a preferable alternative to teach these subjects. Using chess as a tool to teach the overt curriculum can help improve certain cognitive skills, as well as having the potential to propel philosophical ideas and stimulate alternative ways of thought. The goal is to help, however minimally, transform children’s experiences within the schooling institution from one of boredom and detachment to one of curiosity and excitement. -

Jude Acers Miracle Whip

'AGE 16, BERKELEY BARB, SEPT. 6-12, 1974 Jude Acers Miracle Whip It is the game of kings, the most honored, the a simple chess course designed to make you a most played game and sport in the world. chess fiend while enjoying every instant ofthe Learn to play chess very well. Become a lessons. Enter the fascinating world of the chess expert. A professional master presents royal game .... BEGINNER TO EXPERT: A BLITZ CHESS PROGRAM It is possible to win chess tournaments by playing (U.S. Chess Tour, 1970) poorly and lose tournaments while playing extremely THE ROAD well and learning a great deal! A paradox? Hardly. It Part XIV is inevitable that in a long chess match between two players, understanding is what guarantees the victory. by Jude Acers (US senior master) The loser might win a few games with trappy, unsound tactics, but the outcome of such a match is inevitable. It does not matter if you know nothing about the Because you get crushed at first means nothing. So did chessmen or the chessboard. Chess can be learned so Fischer. easily that it is possible to teach and review all of the A loss should mean absolutely nothing but a lesson rules in a single session. Each year on my lecture tour learned. Don't worry about losing. When we get through many thousands of children learn how to play chess and with you, baby, you'll make cheddar cheese of those op keep a record of every move they play! There is nothing ponents that laughed when you sat down to play! to it but fun. -

Llfornia STAGES U.S. TITLE MATCH Everyone I

• "",., ",." rh ~ ' ~ LlFORNIA STAGES U.S. TITLE MATCH Everyone i. in good humor ill> the t en·game match for the United St a t es Champion ship get a under way in Los Ange les. Challenger Herman Steiner ( left) I, determined to prov ide iI worthy follow-up t o h is recent international t riumphs ; Champion Arn old S, Denker (rig ht) exu des qu iet confidence; Cyril Towbin (st anding ), pre,ident of the sponsor ing Los Feliz Chess Club, is announcing the moves t o the audience; and C randmaster Reuben Fine (center) seems t o f i nd the ro le of referee mOlt congenial. • • RUNAWAY BESTSELLER! Now In ItS 48th Thousand by IRVING CHERNEV and KENNETH HARKNESS HIS new Picture Guide to Chess has shattered all sales records for chess books! Published in 1945, more than 27,000 copies were T sol d during the first year! Another 20,000 copies have been printed to supply the ever-increasing demand. A total of 47,600 copies are now in print! Why has this book sold in such quantities? Why have so many people bought An Invitatfon to Chess after looking through all the other chess primers in bookstores? Here are some of the reasons: • An Invitation to Chess teaches the • Part Two gives the reader· athOl rules and basic principles of ch ess by ough g rounding in thtl basic principles III a new, visual·aid method of instruction, chess: The Relative Values of t he Ches!· originated by the editors of CHESS RE· men; The Princlple of Superior Force : VIEW. -

CHESS REVIEW, 2.5 0 Scriptions from Friends the Increased Circula

THE LEADING CHESS MONTHLY News. Pictures. Games. Problems LETTERS CHESS SUGGESTS AMATEUR DEPA RTM ENT REVIEW S i rH : You speak of the possibility of enlarging CHI·:SS H8VIEW if the subscriptions could be VoL IX, No.7, Aug.-Sept., 1941 increased. .\tight I suggest an Amateur De· (WI,'I CIAL DHGAN ()f' 'I'1·m partment? orrel· a year·s subscription and the IJ. S, CH I ~SS F r;])8H,\'i'ION putJli~ation of one 01" his games to every per· EDITOR L A, H orowitz ~on sendiug" in ten lIew subscribers. "M A NAGING EDITOH Kenneth Hal'kness lJENJAM IN K . HA YS, '\1.D. Oxford, N. C. ASSISTANT l~])['l'OR i\\ a tthew Green • DEPARTM I!:N T EDlTORS Subscriber Hays gets his wish. W e will Reu ben Fine- Game o f the Month Vincent L , Eaton- Proble m Department begin an Amatetlr Games Department as soon 11 "villK Cheruev- Ch es8 Qu i ~ as material is available. However, we will PHOT OGRA PI-! ER- Hanu! Echpvel'l'ia exact no conditions, offer no rewards. If read. Publislled monthly October to :\fay, bi-monthly ers will make g ift subscriptions or get sub. June to September. by CHESS REVIEW, 2.5 0 scriptions from friends the increased circula. \Vest 57th Stred, New Yor'k, N. Y. T elephone tion will, of course, enable us to devote more CIrcle 6-8258 . space to this and other departments. S ubscript ions : Oue year $3.00; Two years Amateurs are requested to send in their $5 .50 ; !.' ive yeal'S $12.50 in the United States, games.