Chess S Gary Alan Fine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annex 42 Commission for Women in Chess Batumi, Georgia 29Th

Annex 42 Commission for Women in Chess Batumi, Georgia 29th September 2018, 11.00-13.00 Chairpersons: Susan Polgar (USA), M. Fierro (ECU) Present: N. Cinar (TUR), P. Ambarukwi (INA), D. Chen (TPE), A. Sorokina (BLR), S. Johnson (TTO), U. Umudova (AZE), A. Dimitrijevic (BIH), K. Blackman (BCF), D. Murray (BCF), C. Zhu (QAT), P. Truong (CAM), M. Naugana (MAW), K. Howie (SCO), C. Meyer (USA), R. Haring (USA), U. E. Gronn (NOR), S. Bayat (IRI), S. Rohde (USA), M. Khamboo (NEP), Dr. G. Font (HUN), Dr. N. Short (ENG), A. Karlovych (UKR) MATTERS DISCUSSED At the beginning of the meeting, we addressed the items discussed in the official WOM report submitted to FIDE. The Chairperson (Ms. Polgar) especially praised FIDE for the Women’s World Blitz and Rapid Championships in Saudi Arabia which had a substantially increased prize fund, though it was only one third of the prize in the Open section. The total prize fund in the Women’s championships were $250,000 for each event. Beatriz Marinello reported on her project “Smart Girl” on behalf of the Social Action commission, which included projects in Uganda, Chile, France and the US. This projects seeks to increase participation by girls in chess in those countries. Martha Fierro elaborated on the project about chess in women prisons in Genoa, Italy, which involved the training of refugees in Italy who in turn, train women prisoners. Sophia Rohde from the United States shared some of the work their federation is in doing to promote chess for girls in the USA. They subsequently presented a video showing various interviews with young girls in chess, highlighting the benefits and challenges that they experience in chess. -

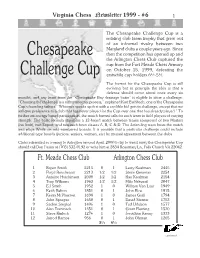

1999/6 Layout

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #6 1 The Chesapeake Challenge Cup is a rotating club team trophy that grew out of an informal rivalry between two Maryland clubs a couple years ago. Since Chesapeake then the competition has opened up and the Arlington Chess Club captured the cup from the Fort Meade Chess Armory on October 15, 1999, defeating the 1 1 Challenge Cup erstwhile cup holders 6 ⁄2-5 ⁄2. The format for the Chesapeake Cup is still evolving but in principle the idea is that a defense should occur about once every six months, and any team from the “Chesapeake Bay drainage basin” is eligible to issue a challenge. “Choosing the challenger is a rather informal process,” explained Kurt Eschbach, one of the Chesapeake Cup's founding fathers. “Whoever speaks up first with a credible bid gets to challenge, except that we will give preference to a club that has never played for the Cup over one that has already played.” To further encourage broad participation, the match format calls for each team to field players of varying strength. The basic formula stipulates a 12-board match between teams composed of two Masters (no limit), two Expert, and two each from classes A, B, C & D. The defending team hosts the match and plays White on odd-numbered boards. It is possible that a particular challenge could include additional type boards (juniors, seniors, women, etc) by mutual agreement between the clubs. Clubs interested in coming to Arlington around April, 2000 to try to wrest away the Chesapeake Cup should call Dan Fuson at (703) 532-0192 or write him at 2834 Rosemary Ln, Falls Church VA 22042. -

The Check Is in the Mail June 2007

The Check Is in the Mail June 2007 NOTICE: I will be out of the office from June 16 through June 25 to teach at Castle Chess Camp in Atlanta, Georgia. During that GM Cesar Augusto Blanco-Gramajo time I will be unable to answer any of your email, US mail, telephone calls, or GAME OF THE MONTH any other form of communication. Cesar’s provisional USCF rating is 2463. NOTICE #2 As you watch this game unfold, you can The email address for USCF almost see Blanco’s rating go upwards. correspondence chess matters has changed to [email protected] RUY LOPEZ (C67) White: Cesar Blanco (2463) ICCF GRANDMASTER in 2006 Black: Benjamin Coraretti (0000) ELECTRONIC KNIGHTS 2006 Electronic Knights Cesar Augusto Blanco-Gramajo, born 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 Nf6 4.0–0 January 14, 1959, is a Guatemalan ICCF Nxe4 5.d4 Nd6 6.Bxc6 dxc6 7.dxe5 Grandmaster now living in the US and Ne4 participating in the 2006 Electronic An unusual sideline that seems to be Knights. Cesar has had an active career gaining in popularity lately. in ICCF (playing over 800 games there) and sports a 2562 ICCF rating along 8.Qe2 with the GM title which was awarded to him at the ICCF Congress in Ostrava in White chooses to play the middlegame 2003. He took part in the great Rest of as opposed to the endgame after 8. the World vs. Russia match, holding Qxd8+. With an unstable Black Knight down Eleventh Board and making two and quick occupancy of the d-file, draws against his Russian opponent. -

JUNE 1950 EVERY SECOND MONTH T BIR.THDAY WEEK.END TOURNA^Rtents T SOUTHSEA TOURNEY T Overseos & N.Z

rTE ]IEW ZEALAII[I Vol. 3-No. 14 JUNE 1950 EVERY SECOND MONTH t BIR.THDAY WEEK.END TOURNA^rtENTS t SOUTHSEA TOURNEY t Overseos & N.Z. Gomes ,1 ts t PROBLEMS + TH E SLAV DEFENCE :-, - t lr-;ifliir -rr.]t l TWO SH ILLIN GS "Jl 3 OIIDSSPLAYBBSe LIBBABY 3 ,,C BOOKS BOOKS H E INTER SOLD BY Fol rvhich tir THE NEW ZEATAND CHESSPLAYER ANNUAL 256 DOMTNION ROAD, LIFI AUCKLAND. PHONE 64-277 (Ne In ordering, merely quote Editor and I catalogue number shown. Postage: Add one penny in every Z/- Champion anr Australia. GAMES G l3-Fifty Great Games of Modern Chess- Golombek. G l-My Best Well annotated. and very gc - _ What son' Games, 1924-32-Alekhine. 120 value. 4/3 games by the greatest player and the greatest annotator. 14/- G l4-Moscow - Prague Match, lg46-The -_ " I take games of exceptional interest Revierv.' Your G 2-Capablanca's Hundred Best Games- to all advanc._ Forest Hills. l p_lay_ery (not recommended beginners Golombek. A book grace for " I have lea, to everv- chess WeII indexed for openings ; and endings. 3/- ancl Purdy's r player's _ library. Well-selected games extensively G l5-Amenities and Background all the other l annotated. 17/G of Che=. bought."-H.A Play-Napier. Delightful liiile book of gre=. G 3-Tarrasch's Best Games-Reinfeld. 1BB " One maga fully annotated games based on Tarrasch,s g_a1es by a master of Chess and writing. 3/- -'eaches chess' own notes. 23/- G 16-Great Britain v. -

May 2020 E S

$3.95 orthwes N t C h May 2020 e s s Northwest Chess On the front cover: May 2020, Volume 74-05 Issue 868 Photo credit: Philip Peterson. ISSN Publication 0146-6941 Published monthly by the Northwest Chess Board. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Office of Record: Northwest Chess c/o Orlov Chess Academy 4174 148th Ave NE, On the back cover: Building I, Suite M, Redmond, WA 98052-5164. Paul Morphy grave. New Orleans, Louisiana. Photo credit: Philip Peterson. Periodicals Postage Paid at Seattle, WA USPS periodicals postage permit number (0422-390) NWC Staff Chesstoons: Editor: Jeffrey Roland, Chess cartoons drawn by local artist Brian Berger, [email protected] of West Linn, Oregon. Games Editor: Ralph Dubisch, [email protected] Publisher: Duane Polich, Submissions [email protected] Business Manager: Eric Holcomb, Submissions of games (PGN format is preferable for games), [email protected] stories, photos, art, and other original chess-related content are encouraged! Multiple submissions are acceptable; please indicate if material is non-exclusive. All submissions are subject Board Representatives to editing or revision. Send via U.S. Mail to: Chouchanik Airapetian, Eric Holcomb, Jeffrey Roland, NWC Editor Alex Machin, Duane Polich, Ralph Dubisch, 1514 S. Longmont Ave. Jeffrey Roland, Josh Sinanan. Boise, Idaho 83706-3732 or via e-mail to: Entire contents ©2020 by Northwest Chess. All rights reserved. [email protected] Published opinions are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editor or the Northwest Chess Board. Northwest Chess is the official publication of the chess Northwest Chess Knights governing bodies of the states of Washington and Idaho. -

Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames

Games of No Chance MSRI Publications Volume 29, 1996 Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames LEWIS STILLER Abstract. This article has three chief aims: (1) To show the wide utility of multilinear algebraic formalism for high-performance computing. (2) To describe an application of this formalism in the analysis of chess endgames, and results obtained thereby that would have been impossible to compute using earlier techniques, including a win requiring a record 243 moves. (3) To contribute to the study of the history of chess endgames, by focusing on the work of Friedrich Amelung (in particular his apparently lost analysis of certain six-piece endgames) and that of Theodor Molien, one of the founders of modern group representation theory and the first person to have systematically numerically analyzed a pawnless endgame. 1. Introduction Parallel and vector architectures can achieve high peak bandwidth, but it can be difficult for the programmer to design algorithms that exploit this bandwidth efficiently. Application performance can depend heavily on unique architecture features that complicate the design of portable code [Szymanski et al. 1994; Stone 1993]. The work reported here is part of a project to explore the extent to which the techniques of multilinear algebra can be used to simplify the design of high- performance parallel and vector algorithms [Johnson et al. 1991]. The approach is this: Define a set of fixed, structured matrices that encode architectural primitives • of the machine, in the sense that left-multiplication of a vector by this matrix is efficient on the target architecture. Formulate the application problem as a matrix multiplication. -

THE LEADING CHESS MOIITHLY News

THE LEADING CHESS MOIITHLY News. Pictures. Games. Problems • Learn winning technique from Rubinstein's brilliant games you CAN GET more practical information on how to play winning chess by study Rubinstein (Black) Won ing the games of the great RUBINSTEIN than in Four Crushing Moves! you could obtain from a dozen theoretical text-books. 1 ... RxKtl! By playing over the selections in "Rubin stein's Chess Masterpieces," you will see for 2 PxQ yourself how this great strategist developed R.Q7!! his game with accuracy and precision, over 3 QxR came his world-renowned opponents with BxBch crushing blows in the middle-game or with superb, polished technique in the end-game, 4 Q-Kt2 There is no beller or more pleasant way of R·HS!! inproving your knowledge of chess. You will 5 Resigns enjoy these games for their entertainment value alone. You will learn how to apply the This startling combination from Ru underlying principles of Rubinstein's winning binstein's "Immortal Game" reveals technique to your own games. Complete and his great genius and shows how the thorough annotations explain the intricacies Grandmaster used "blitz-krieg" tac of Rubinstein's play, help you to understand tics when given the opportunity. the motives and objectives. CREATIVE GENIUS REVEALED IN GAMES See Page 23 of this new book con Rubinstein has added more to chess theory taining 100 of Rubinstein's brilliant. and technique than any other master in the instructive games. Just published. past 30 years! His creative genius is revealed Get your copy NOW. in this book. -

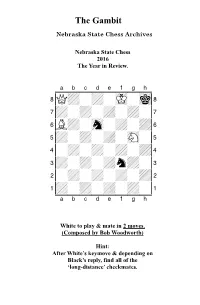

2016 Year in Review

The Gambit Nebraska State Chess Archives Nebraska State Chess 2016 The Year in Review. XABCDEFGHY 8Q+-+-mK-mk( 7+-+-+-+-' 6L+-sn-+-+& 5+-+-+-sN-% 4-+-+-+-+$ 3+-+-+n+-# 2-+-+-+-+" 1+-+-+-+-! xabcdefghy White to play & mate in 2 moves. (Composed by Bob Woodworth) Hint: After White’s keymove & depending on Black’s reply, find all of the ‘long-distance’ checkmates. Gambit Editor- Kent Nelson The Gambit serves as the official publication of the Nebraska State Chess Association and is published by the Lincoln Chess Foundation. Send all games, articles, and editorial materials to: Kent Nelson 4014 “N” St Lincoln, NE 68510 [email protected] NSCA Officers President John Hartmann Treasurer Lucy Ruf Historical Archivist Bob Woodworth Secretary Gnanasekar Arputhaswamy Webmaster Kent Smotherman Regional VPs NSCA Committee Members Vice President-Lincoln- John Linscott Vice President-Omaha- Michael Gooch Vice President (Western) Letter from NSCA President John Hartmann January 2017 Hello friends! Our beloved game finds itself at something of a crossroads here in Nebraska. On the one hand, there is much to look forward to. We have a full calendar of scholastic events coming up this spring and a slew of promising juniors to steal our rating points. We have more and better adult players playing rated chess. If you’re reading this, we probably (finally) have a functional website. And after a precarious few weeks, the Spence Chess Club here in Omaha seems to have found a new home. And yet, there is also cause for concern. It’s not clear that we will be able to have tournaments at UNO in the future. -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

David Bronstein

The Rise and Fall of David Bronstein Genna Sosonko The Rise and Fall of David Bronstein Author: Genna Sosonko Managing Editor: Ilan Rubin, Founder and CEO, LLC Elk and Ruby Publishing House (www.elkandruby.ru) Translated from the Russian by Ilan Rubin Edited by Reilly Costigan-Humes Typesetting by Andrei Elkov (www.elkov.ru) Artwork by Sergey Elkin First published in Russia in 2014 © LLC Elk and Ruby Publishing House, 2017 (English version). All rights reserved © Genna Sosonko and Andrei Elkov, 2014 (Russian original). All rights reserved ISBN 978-5-9500433-1-4 Foreword by Garry Kasparov David Bronstein – Chess Innovator It gives me immense pleasure to introduce the first English edition of Genna Sosonko’s book The Rise and Fall of David Bronstein, a work devoted to the life and times of a brilliant grandmaster who was just a step away from reaching the very summit of Mount Olympus, and who, in terms of his understanding of the game, undoubtedly belonged to the world champions’ club. Bronstein’s games were full of original, fresh solutions and exciting, amazing ideas nobody had ever come up with before. He possessed a unique vision of the chess board and was irresistibly drawn to unconventionality. Sometimes, ingenious concepts were hidden behind this unconventionality, ones that proved to be way ahead of their time. Bronstein stands out from post-war generation grandmasters in terms of the sheer volume of his contribution to chess. He was one of the game’s greatest popularizers. Take his famous book Zurich International Chess Tournament (1953), for instance: he wrote a truly iconic middle-game textbook based on the analysis of that super-tournament’s games that proved to be useful even for average players. -

What's Wrong with David?

• America j Chil:U neWJpaper Copyright 1956 by United States Cheso F&deratlon _~~~~!,"-~I~Vol. X, o. __________________________________T"h~,"~'"da"~,~Ju"~ly~5",_'"9"5~6 _ ________________________________________ ~15ocCO'on~t=' __ What's Wrong With David? Conduclltd by PO$;riotl Nv. IS; By International Master GEORGE KOLTANOWSKI Contributed by RUSSELL CHAUVENiT N 1950 David Bronstein of the USSR won the C:andid.ates' Tourn~me.nt RICHARD McLELLAN I ill Budapest. In 1951 he played a match WIth Mikhael Botvmruk, END solutions to Position No. cbampion of the world, for the title, in Moscow. The match ended. in a S 187 to reach Russell Cbauvenet, tie 12-12. Many are the players, who saw the games, who are convlOc~d 721 Gist Ave., Silver Spring. Md., that Botvinnik should have lost this match and with it the title. DaVid by August 5, 1956. With your solu had considcrablc success since then. His style b on the bizarre, he has tion, please send analysis or rea no set rulC's of opening plays. One can almost say his ideas are fan sons supporting your choice of tastic. and seldom can one play ovet a game of his, and say it was dull. "Best Move" or moves. In the Candidates' Tournament in Zurich, 1953, he beat Reshevsky IS. KR·KKtl 0 ·0 32. RxRch K>' Solution to Position No. 1117 will ap 16. K· Kt2 8-Q2 33. K·Rl R·B4 twice, so that his forthcoming 17. P·R4 8·K93 34. Q·R4 Kt_B3 pear in the August 10, 1956 issue. -

George Koltanowski: Father of Northern California Chess

GEORGE KOLTANOWSKI: FATHER OF NORTHERN CALIFORNIA CHESS Chess flourished during the Great Depression, but when World War II started the entire country was galvanized to defeat the Axis. Chess interest went into hibernation: or would have, if not for a small group of masters like Kolty. Of course, everyone knows that he set the world’s blindfold record in September of 1937. What they may not know, is that after he received a U.S. visa in 1940, he spent the next 7 years criss‐crossing the country promoting chess with exhibitions and lectures. Post war Northern California was a chess desert. Most of the chess clubs had dissolved before or during the war. The only two that were left, the Mechanics’ Institute Chess Room and the Sacramento Chess Club, stood in isolation. It wasn’t until 1947 when he settled down in Santa Rosa, California, that the Northern California chess clubs and chess league started re‐forming again. It wasn’t a coincidence; he jumpstarted dozens of chess clubs, city by city, via lectures, and simultaneous and blindfold exhibitions…he was a fantastic showman. His first column, in 1947, was for the Santa Rosa Press Democrat. A year later he started writing a column for the San Francisco Chronicle. In November, 1947 he launched his first magazine called appropriately ‘California Chess News’. It ran through 1949, after which it changed its name to ‘Chess Digest’. ‘Chess Digest’ folded on December of 1950. (See http://www.chessdryad.com/articles/lawless/art_12.htm) After he moved to San Francisco in 1949, he continued to promote chess at the individual, club and city level.