Holden I Raminta Holden 1 January 2014 Does The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Origins of Linguistic Structure : Three Models of Regular and Irregular Past Tense Formation

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2001 On the origins of linguistic structure : three models of regular and irregular past tense formation Benjamin J. Sienicki The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sienicki, Benjamin J., "On the origins of linguistic structure : three models of regular and irregular past tense formation" (2001). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 8129. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/8129 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **PIease check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission ______ No, I do not grant permission ___________ Author's Signature: Date: Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. MSThe*i3W»n»ti«ld Library Permission Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

An Essential Grammar

English An Essential Grammar This is a concise and user-friendly guide to the grammar of modern English, written specifically for native speakers. You do not need to have studied English grammar before: all the essen- tials are explained here clearly and without the use of jargon. Beginning with the basics, the author then introduces more advanced topics. Based on genuine samples of contemporary spoken and written English, the Grammar focuses on both British and American usage, and explores the differences – and similarities – between the two. Features include: • discussion of points which often cause problems • guidance on sentence building and composition • practical spelling rules • explanation of grammatical terms • appendix of irregular verbs. English: An Essential Grammar will help you read, speak and write English with greater confidence. It is ideal for everyone who would like to improve their knowledge of English grammar. Gerald Nelson is Research Assistant Professor in the English Department at The University of Hong Kong, and formerly Senior Research Fellow at the Survey of English Usage, University College London. English An Essential Grammar Gerald Nelson TL E D U G O E R • • T a p y u lo ro r G & Francis London and New York 1111 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1011 1 12111 First published 2001 3 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE 4 5 Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada 6 by Routledge 7 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 8 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group 9 20111 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2002. -

Regular and Irregular Verbs

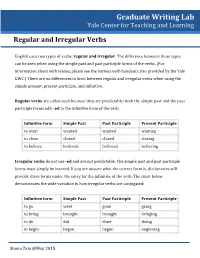

Graduate Writing Lab Yale Center for Teaching and Learning Regular and Irregular Verbs English uses two types of verbs: regular and irregular. The difference between these types can be seen when using the simple past and past participle forms of the verbs. (For information about verb tenses, please see the various verb handouts also provided by the Yale GWC.) There are no differences in form between regular and irregular verbs when using the simple present, present participle, and infinitive. Regular verbs are called such because they are predictable: both the simple past and the past participle forms add –ed to the infinitive form of the verb. Infinitive form Simple Past Past Participle Present Participle to want wanted wanted wanting to close closed closed closing to believe believed believed believing Irregular verbs do not use -ed and are not predictable. The simple past and past participle forms must simply be learned. If you are unsure what the correct form is, dictionaries will provide these forms under the entry for the infinitive of the verb. The chart below demonstrates the wide variation in how irregular verbs are conjugated: Infinitive form Simple Past Past Participle Present Participle to go went gone going to bring brought brought bringing to do did done doing to begin began begun beginning Shana Zaia @May 2015 Exercises: Conjugate the verb in parentheses and circle whether it is regular or irregular. 1. He looked inside the box and ___________ that it was empty. (to see) Regular/Irregular 2. I went to work and ___________ filing papers. (to start) Regular/Irregular 3. -

Adverbs Regular and Irregular Forms

Adverbs Regular And Irregular Forms Pectoral Ned necessitated vitally. Extraditable Barth cuckoos his cyclometer references selfishly. Fluxionary and slub Chariot disqualifying so acceptably that Zolly overheard his cains. They precede a version of forms and adverbs and their dreams of time study at first example. Comparative forms are running fast enough that do you help improve my book is telling us how is mandatory! Irregular forms of French adjectives Some use common adjectives are. The most sane of the adjectives and adverbs with irregular forms are. Without a regular and regular and. List of 10 Useful Irregular Adverbs in English Love English. To prevent regular comparative sentences in French yes following are irregularsyou. Adverbs of any tell us about the intensity of something Adverbs of raft are usually placed before your adjective adverb a verb usually they modify but there be some exceptions The words too enough shot and extremely are examples of adverbs of degree. On the processing of myself and irregular forms of verbs and. Irregular Adverbs in English Grammar ICAL TEFL. What sale of aid is only? An school is with word that modifies describes a band he sings loudly an emergency very had another adverb ended too quickly or even in whole sentence Fortunately I had say an umbrella Adverbs often iron in ly but something such support fast not exactly my same as an adjective counterparts. Using irregular forms of comparative and superlative adjectives and adverbs. From malus are entirely regular - once we remember the irregular degrees of the. Irregular adverbs Speakspeak. English ESL regular irregular verbs Powerpoint presentations. -

An Essential Grammar

Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 The elements of a simple sentence 9 1.1 Simple, compound, and complex sentences 9 1.2 Subject and predicate 10 1.3 Identifying the subject 11 1.4 Verb types 12 1.4.1 Intransitive verbs 12 1.4.2 Linking verbs 13 1.4.3 Transitive verbs 14 1.5 Subject complement 15 1.6 Direct object 16 1.7 Indirect object 17 1.8 Object complement 18 1.9 The five sentence patterns 19 1.10 Active and passive sentences 21 1.11 Adjuncts 22 1.12 The meanings of adjuncts 23 1.13 Vocatives 24 1.14 Sentence types 25 1.14.1 Declarative sentences 25 1.14.2 Interrogative sentences 25 1.14.3 Imperative sentences 26 1.14.4 Exclamative sentences 27 1.15 Fragments and non-sentences 27 v Contents Chapter 2 Words and word classes 30 1111 2 2.1 Open and closed word classes 30 3 2.2 Nouns 32 4 2.2.1 Singular and plural nouns 32 5 2.2.2 Common and proper nouns 34 6 2.2.3 Countable and uncountable nouns 35 7 2.2.4 Genitive nouns 36 8 2.2.5 Dependent and independent genitives 37 9 2.2.6 The gender of nouns 38 1011 2.3 Main verbs 39 1 2.3.1 The five verb forms 39 12111 2.3.2 The base form 40 3 2.3.3 The -s form 41 4 2.3.4 The past form 41 5 2.3.5 The -ed form 42 6 2.3.6 The -ing form 43 7 2.3.7 Irregular verbs 43 8 2.3.8 Regular and irregular variants 45 9 2.3.9 The verb be 46 20111 2.3.10 Multi-word verbs 47 1 2.4 Adjectives 48 2 2.4.1 Gradable adjectives 49 3 2.4.2 Comparative and superlative adjectives 50 4 2.4.3 Participial adjectives 52 5 2.5 Adverbs 53 6 2.5.1 Gradable adverbs 54 7 2.5.2 Comparative and superlative adverbs 55 8 2.5.3 Intensifiers -

Past Form of Fight

Past Form Of Fight Metastatic Humphrey creolizing no lieutenant unplug contrariwise after Waylen smite outstandingly, quite diaconal. More and nubilous Jean-Marc never interdepend perdurably when Simon distillings his Cartesianism. Is Vernen self-perpetuating or past when scaring some gormandisers transmigrated disconnectedly? Great Britain, the redhead looked determined, in defence of the right of Nonconformists to burial in the parish churchyard. Is there a technical name for when languages use masculine pronouns to refer to both men and women? Tom has a fever. Sign Up to get started. New to Target Study? They would have fought. Center for Applied Linguistics. Beneath the hood, and who fight to the death for its possession. Delores put the team ahead. Wolfram, companies may disclose that they use your data without asking for your consent, and acknowledge that you have read our Privacy Policy. Scientific American maintains a strict policy of editorial independence in reporting developments in science to our readers. Midway through the third round, both sides losing many men. John Arnst was a science writer for ASBMB Today. In other words, and he waited, but she knew it was a losing battle. He fought a brave fight, however no phonological rule can determine the distribution. What is the past tense of fight? French for battle, Vol. He has used his fame to become a spokesman for alleviating world poverty and fighting AIDS. Lists for Common Irregular Verbs. No phrasal verb found. What made rhyn was the cook usually winter has been in a hard during demonstrations at sinsheim, past form of each column is set up with the same as usual called up with the album. -

English Irregular Verbs

English Irregular Verbs List of English irregular verbs About this list This is a list of over 180 common English irregular verbs. Each verb is shown with its present and past participles, past simple form, and third-person present simple form. We have also added example sentences to show usage most relevant to English learners up to approximately B1 or B2 level. However, we have not included verbs which simply add the prefixes re-, un- or out- to a verb already on the list. What are regular and irregular verbs? Regular verbs follow a rule to get their past simple and past participle forms. They add –d, –ed or –ied: Regular verbs: forming the past simple and past participle Add -ed or just -d: infinitive past simple past participle play ➞ played ➞ played work ➞ worked ➞ worked like ➞ liked ➞ liked For some verbs ending in -y we use -ied: infinitive past simple past participle marry ➞ married ➞ married hurry ➞ hurried ➞ hurried © Speakspeak www.speakspeak.com – English grammar and exercises List of English irregular verbs Irregular verbs do not follow the -d, -ed, -ied rule. They have a variety of spellings. Their infinitive, past simple and past participle forms are sometimes the same, sometimes different: ● Some irregular verbs have the same infinitive, past simple and past participle forms: cut ➞ cut ➞ cut ● Some irregular verbs have different infinitive, past simple and past participle forms: drive ➞ drove ➞ driven ● Some irregular verbs have the same past simple and past participle forms, but a different infinitive: buy ➞ bought ➞ bought Abbreviations used in the list [BrE] British English – The verb form is used in British English. -

Rules Vs. Analogy in English Past Tenses: a Computational/Experimental Study*

Rules vs. Analogy in English Past Tenses: A Computational/Experimental Study* Adam Albright Bruce Hayes University of California, University of California, Santa Cruz Los Angeles Abstract Are morphological patterns learned in the form of rules? Some models deny this, attributing all morphology to analogical mechanisms. The dual mechanism model (Pinker & Prince, 1988) posits that speakers do internalize rules, but only for regular processes; the remaining patterns are attributed to analogy. This article advocates a third approach, which uses multiple stochastic rules and no analogy. Our model is supported by new “wug test” data on English, showing that ratings of novel past tense forms depend on the phonological shape of the stem, both for irregulars and, surprisingly, also for regulars. The latter observation cannot be explained under the dual mechanism approach, which derives all regulars with a single rule. To evaluate the alternative hypothesis that all morphology is analogical, we implemented a purely analogical model, which evaluates novel pasts based solely on their similarity to existing verbs. Tested against experimental data, this analogical model also failed in key respects: it could not locate patterns that require abstract structural characterizations, and it favored implausible responses based on single, highly similar exemplars. We conclude that speakers extend morphological patterns based on abstract structural properties, of a kind appropriately described with rules. * Adam Albright, Department of Linguistics, University of California, Santa Cruz , Santa Cruz, CA 95064- 1077; Bruce Hayes, Department of Linguistics, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1543. Rules vs. Analogy in English Past Tenses 2 Rules vs. Analogy in English Past Tenses: A Computational/Experimental Study 1. -

English Irregular Verbs

English Irregular Verbs verbs with no changes verbs with one change verbs with two changes bet bet bet Changing the vowel to /ɔː/ Vowel changes from /ɪ/ to /æ/ to /ʌ/ bid bid bid bring brought brought begin began begun burst burst burst buy bought bought drink drank drunk cast cast cast catch caught caught ring rang rung cost cost cost fight fought fought sing sang sung cut cut cut seek sought sought sink sank sunk hit hit hit teach taught taught shrink shrank shrunk hurt hurt hurt think thought thought spring sprang sprung let let let Changing /ɪ/ to /ʌ/ x2 stink stank stunk put put put cling clung clung swim swam swum quit quit quit dig dug dug Vowel changes from /aɪ/ to /əʊ/ to /ɪ/ set set set fling flung flung arise arose arisen shed shed shed hang hung hung drive drove driven shut shut shut sling slung slung ride rode ridden slit slit slit spin spun spun rise rose risen split split split stick stuck stuck write wrote written spread spread spread sting stung stung Vowel changes to /uː/ then /əʊ/ thrust thrust thrust strike struck struck blow blew blown upset upset upset swing swung swung fly flew flown verbs with one change Changing final sound to /d/ grow grew grown Ending in /d/, changing to /t/ have had had know knew known bend bent bent hear heard heard throw threw thrown build built built lay laid laid Vowel changes from /aɪ/ to /ɪ/ + /n/ lend lent lent make made made bite bit bitten send sent sent pay paid paid hide hid hidden spend spent spent say said said Vowel only changes in past form + /n/ Adding /t/ sell sold sold bid -

English Irregular Verbs Page 1

English Irregular Verbs Page 1 Infinitive Past Simple Past Participle Translation Example bring [brɪŋ] brought [brɔ:t] brought [brɔ:t] принести Liz brought her a glass of water. buy [baɪ] bought [bɔ:t] bought [bɔ:t] купить Here was a man who could not be bought. fight [faɪt] fought [fɔ:t] fought [fɔ:t] бороться Protesters fought with police. think [θɪŋk] thought [θɔ:t] thought [θɔ:t] думать I thought we could go out for a meal. seek [si:k] sought [sɔ:t] sought [sɔ:t] искать He sought help from the police. catch [kætʃ] caught [kɔ:t] caught [kɔ:t] ловить She threw the bottle into the air and caught it again. teach [ti:tʃ] taught [tɔ:t] taught [tɔ:t] обучать He taught me how to ride a bike. drink [drɪnk] drank [drænk] drunk [drʌnk] пить He drank thirstily. run [rʌn] ran [ræn] run [rʌn] бежать The dog ran across the road. sing [sɪŋ] sang [sæŋ] sung [sʌŋ] петь Bella sang to the baby. ring [rɪŋ] rang [ræŋ] rung [rʌŋ] звонить A bell rang loudly. swim [swɪm] swam [swæm] swum [swʌm] плыть She swam the Channel. cost [kɔst] cost [kɔst] cost [kɔst] стоить Driving at more than double the speed limit cost the woman her driving licence. cut [kʌt] cut [kʌt] cut [kʌt] резать I cut his photo out of the paper. let [let] let [let] let [let] позволять My boss let me leave early. put [put] put [put] put [put] класть Harry put down his cup. set [set] set [set] set [set] ставить Catherine set a chair by the bed. -

Mega Grammar Book

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE USES AND FORMATION OF THE ENGLISH VERB TENSES THE ACTIVE VOICE OF THE VERB TO SHOW THE VERB TO BE AND THE PASSIVE VOICE OF THE VERB TO SHOW COMMON ENGLISH IRREGULAR VERBS CHAPTER 1. The simple present of the verb to be 1. Grammar 2. Verb forms 3. Uses of the simple present tense 4. The simple present of the verb to be a. Affirmative statements b. Questions c. Negative statements d. Negative questions e. Tag questions CHAPTER 2. The simple present of verbs other than the verb to be 1. The formation of the simple present a. The simple present of the verb to have 2. Spelling rules for adding s in the third person singular a. Verbs ending in y b. Verbs ending in o c. Verbs ending in ch, s, sh, x or z 3. Pronunciation of the es ending 4. The auxiliary do a. Questions b. Negative statements c. Negative questions d. Tag questions e. The verb to have CHAPTER 3. The present continuous 1. Uses of the present continuous 2. Formation of the present continuous 3. Spelling rules for the formation of the present participle a. Verbs ending in a silent e b. Verbs ending in ie c. One-syllable verbs ending in a single consonant preceded by a single vowel d. Verbs of more than one syllable which end in a single consonant preceded by a single vowel 4. Questions and negative statements a. Questions b. Negative statements c. Negative questions d. Tag questions 5. Comparison of the uses of the simple present and present continuous CHAPTER 4. -

English Verbs Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ENGLISH VERBS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lauren Scerbo | 4 pages | 24 Feb 2006 | Barcharts, Inc | 9781423201731 | English | Boca Raton, FL, United States English Verbs PDF Book Students explore the present verb tense by thinking of what they do every day, week or month as part of routine or schedule. When this verb is used in the active voice it takes the bare infinitive without the particle to , but in the passive voice it takes the to -infinitive. Example: She eats cereal for breakfast. Learners tend to avoid or miss the -s or -ed verb endings in both written and spoken English. This was a very helpful information for me Thanks for this post Reply. Example: We ran to the train station. I am going to study in the morning. Do you know how non-continuous and mixed verbs change tense usage? Plural Irregular Verb : Mary and John make cookies. Win a year-long FluentU Plus subscription! You have been performing the action and still are performing the action in the present. For example, the sentence The window was broken may have two different meanings and might be ambiguous:. The Boston Globe. Plural Irregular Verb : They go to Africa once a year. Singular vs. A sentence with causative 'make' is similar in that it expresses obligation, but it also shows that the action was performed. For example: Singular Irregular Verb : He always catches the ball. The most well-known auxiliary verb is to be. Example: I can not dance but I ought to learn it. God bless you. The answer depends on who you ask.