07-William Altman.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Have the Belgians Ever Done for Us? an Iron Age Mystery

What have the Belgians ever done for us? An Iron Age mystery Up until recently many accounts of the history of Wheathampstead confidently stated that the first settlers came from Belgium. “Sometime after 100B.C. a sophisticated group of invaders from the continent moved up the rivers Thames and Lea. They came from the area which is today Belgium. These Belgae made the first permanent settlements in the area.” (WEA 1973, p12). Who were these mysterious and ‘sophisticated’ Belgians who founded Wheathampstead? An equally interesting question is why have references to Belgic invaders largely disappeared from recent history books? Solving the puzzle The Belgic invasion theory emerged in the late nineteenth century as a solution to a puzzle. Why was there a lack of middle Iron Age archaeological finds in southeast Britain? While there was evidence of earlier occupation the absence of archaeological finds suggested that southeast Britain had been unsettled in the mid Iron Age up to around 150BC. After this date Victorian archaeologists were able to identify a great deal of evidence of intensive activity and occupation, including the building of hill forts in the southeast and locally the Devil’s Dyke in Wheathampstead. What prompted this dramatic change? A dig in Kent An archaeological excavation in 1890 provided a strong clue. This dig was carried out by Arthur Evans who would later become world famous for excavating the Palace of Knossos on Crete. Evans investigated a late Iron Age cemetery at Aylesford in Kent and he pointed out that the finds were strikingly similar to Belgic cemeteries on the continent. -

Phases of Irish History

¥St& ;»T»-:.w XI B R.AFLY OF THE UNIVERSITY or ILLINOIS ROLAND M. SMITH IRISH LITERATURE 941.5 M23p 1920 ^M&ii. t^Ht (ff'Vj 65^-57" : i<-\ * .' <r The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. University of Illinois Library • r m \'m^'^ NOV 16 19 n mR2 51 Y3? MAR 0*1 1992 L161—O-1096 PHASES OF IRISH HISTORY ^.-.i»*i:; PHASES OF IRISH HISTORY BY EOIN MacNEILL Professor of Ancient Irish History in the National University of Ireland M. H. GILL & SON, LTD. so UPPER O'CONNELL STREET, DUBLIN 1920 Printed and Bound in Ireland by :: :: M. H. Gill &> Son, • • « • T 4fl • • • JO Upper O'Connell Street :: :: Dttblin First Edition 1919 Second Impression 1920 CONTENTS PACE Foreword vi i II. The Ancient Irish a Celtic People. II. The Celtic Colonisation of Ireland and Britain . • • • 3^ . 6i III. The Pre-Celtic Inhabitants of Ireland IV. The Five Fifths of Ireland . 98 V. Greek and Latin Writers on Pre-Christian Ireland . • '33 VI. Introduction of Christianity and Letters 161 VII. The Irish Kingdom in Scotland . 194 VIII. Ireland's Golden Age . 222 IX. The Struggle with the Norsemen . 249 X. Medieval Irish Institutions. • 274 XI. The Norman Conquest * . 300 XII. The Irish Rally • 323 . Index . 357 m- FOREWORD The twelve chapters in this volume, delivered as lectures before public audiences in Dublin, make no pretence to form a full course of Irish history for any period. -

1 Gallo-Roman Relations Under the Early Empire by Ryan Walsh A

Gallo-Roman Relations under the Early Empire By Ryan Walsh A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Ancient Mediterranean Cultures Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Ryan Walsh 2013 1 Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This paper examines the changing attitudes of Gallo-Romans from the time of Caesar's conquest in the 50s BCE to the start of Vespasian's reign in 70-71 CE and how Roman prejudice shaped those attitudes. I first examine the conflicted opinions of the Gauls in Caesar's time and how they eventually banded together against him but were defeated. Next, the activities of each Julio-Claudian emperor are examined to see how they impacted Gaul and what the Gallo-Roman response was. Throughout this period there is clear evidence of increased Romanisation amongst the Gauls and the prominence of the region is obvious in imperial policy. This changes with Nero's reign where Vindex's rebellion against the emperor highlights the prejudices still effecting Roman attitudes. This only becomes worse in the rebellion of Civilis the next year. After these revolts, the Gallo-Romans appear to retreat from imperial offices and stick to local affairs, likely as a direct response to Rome's rejection of them. -

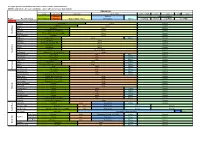

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

DBG Book 1 Outline

Caesar’s De Bello Gallico BOOK I OUTLINE Chapter I 1-4 Gaul has three parts, inhabited by three tribes (Belgae, Aquitaini, and Celtae/Galli) who are different in language, institutions, and laws. 4-5. The rivers that separate the three areas. 6-11. Three reasons why the Belgae are the bravest. 11-15. The final reason explains why the Helvetians surpass the other Gauls in courage, because they fight regularly with the Germans, either in Germania or in their own land. 15-18. The boundaries of the land the Gauls occupy. 18-21. The boundaries of the land the Belgae occupy. 21-24. The boundaries of the land the Aquitani occupy. Chapter II 1-6. The richest and noblest Helvetian made a conspiracy among the nobility because of a desire for power and persuaded his people to leave their land with the argument that because of their surpassing courage they would easily get control of all Gaul. 6-12. He easily swayed them because the Helvetians were hemmed in on all sides by natural barriers. 12-15. As a result they had less freedom of movement and were less able to wage war against their neighbors, and thus their warriors were afflicted with great sorrow. 15-18. They considered their land, 240 miles by 180 miles, too small in comparison with their numbers and their glory in war. Chapter III 1-6 Persuaded by their situation and the authority of Orgetorix, the Helvetians decide to get ready for departure: they buy all the wagons and pack animals they can; plant as many crops as possible for supplies on the trip, and make alliances with the nearest states. -

Oratio Recta and Oratio Obliqua in Caesar's De Bello

VOICES OF THE ENEMY: ORATIO RECTA AND ORATIO OBLIQUA IN CAESAR’S DE BELLO GALLICO by RANDY FIELDS (Under the Direction of James C. Anderson, jr.) ABSTRACT According to his contemporaries and critics, Julius Caesar was an eminent orator. Despite the lack of any extant orations written by Caesar, however, one may gain insight into Caesar’s rhetorical ability in his highly literary commentaries, especially the De Bello Gallico. Throughout this work, Caesar employs oratio obliqua (and less frequently oratio recta) to animate his characters and give them “voices.” Moreover, the individuals to whom he most frequently assigns such vivid speeches are his opponents. By endowing his adversaries in his Commentarii with the power of speech (with exquisite rhetorical form, no less), Caesar develops consistent characterizations throughout the work. Consequently, the portrait of self-assured, unification-minded Gauls emerges. Serving as foils to Caesar’s own character, these Gauls sharpen the contrast between themselves and Caesar and therefore serve to elevate Caesar’s status in the minds of his reader. INDEX WORDS: Caesar, rhetoric, oratory, De Bello Gallico, historiography, propaganda, opponent, oratio obliqua, oratio recta VOICES OF THE ENEMY: ORATIO RECTA AND ORATIO OBLIQUA IN CAESAR’S DE BELLO GALLICO by RANDY FIELDS B.S., Vanderbilt University, 1992 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2005 © 2005 Randy Fields All Rights Reserved VOICES OF THE ENEMY: ORATIO RECTA AND ORATIO OBLIQUA IN CAESAR’S DE BELLO GALLICO by RANDY FIELDS Major Professor: James C. -

That's the Question

Romanization or not Romanization – that’s the Question Indisier på romanisering i den første boken av Caesars De Bello Gallico Master i Historie – HI320S Vår 2011 Universitetet i Nordland Fakultet for Samfunnsvitenskap Michèle Gabathuler Takk… …til veilederen min Per-Bjarne Ravnå, som har vært uendelig tålmodig og som har ledet meg tilbake på veien igjen når jeg har gått meg vill så mange ganger. Takk for gode råd, tipps og ideer, og ikke minst for at du tok imot utfordringen med å veilede en sveitser som skriver som Yoda snakker og som er glad i å finne opp egne norske ord som ingen andre enn meg forstår. …til dere alle som måtte tåle mitt åndsfravær når vi var sammen, som måtte høre på meg legge ut om hvor artig og spennende det er å skrive om dette temaet, som måtte svare på alle slags rare spørsmål i forbindelse med oppgava mi, og som måtte oppleve entusiasmen min om dere ville eller ikke. …til dere alle som også måtte høre på sytingen min når berg- og dalbanen hadde nådd et lavpunkt igjen, der jeg syntes at det her aldri kommer til å gå bra. Takk for at dere sa “jo, det her kommer til å gå bra. Stå på.” Merci villmol allna eu! Michèle Gabathuler Bodø, 15.05.2011 1 ::ruuus::fUU'U6:n.n..tLtS C ...."SA~".~SA~ \4oI\R~ Pf!R1E5PeRIESPeReS f.G1lSKeRf.4IER6K1iR'1-4ER6~~. R\AI\Al. 1b9'PEN~1tWÆN AV SfNstNSI'N KA~I'GRGKAR'1IZ~KA~~" PRØMT"5~M'T'5ORØM1li irj ARET 50 F. -

Celtic Britain

1 arfg Fitam ©0 © © © © ©©© © © © © © © 00 « G XT © 8 i imiL ii II I IWtv,-.,, iM » © © © © © ©H HWIW© llk< © © J.Rhjsffi..H. © I EARLY BRITAIN, CELTIC BRITAIN. BY J. RHYS, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon/). Honorary LL.D. (Edin.). Honorary D.Litt. (Wales). FROFESSOR OF CELTIC IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD J PRINCIPAL OF JESUS COLLEGE, AND LATE FELLOW OF MERTON COLLEGE FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY. WITH TWO MAPS, AND WOODCUTS OF COIliS, FOURTH EDITION. FUBLISHED UNDER THE D.RECTION OF THE GENERAL LITERATURE COMMITTEE. LONDON: SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE, NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C. ; 43, queen victoria street, e.c. \ Brighton: 129, north street. New York : EDWIN S. GORHAM. iqoP, HA 1^0 I "l C>9 |X)VE AND MALCOMSON, LIMITED, PRINTERS, 4 AND 5, DEAN STREET, HIGH HOLBORN, LONDON, W.C. PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. These are the days of little books, and when the author was asked to add one to their number, he accepted the invitation with the jaunty simplicity of an inexperienced hand, thinking that it could not give him much trouble to expand or otherwise modify the account given of early Britain in larger works ; but closer acquaintance with them soon convinced him of the folly of such a plan— he had to study the subject for himself or leave it alone. In trying to do the former he probably read enough to have enabled him to write a larger work than this ; but he would be ashamed to confess how long it has occupied him. As a student of language, he is well aware that no severer judgment could be passed on his essay in writing history than that it should be found to be as bad as the etymologies made by historians are wont to be ; but so essential is the study of Celtic names to the elucidation of the early history of Britain that the risk is thought worth incurring. -

Julius Caesar's System Understanding

JULIUS CAESAR’S SYSTEM UNDERSTANDING OF THE GALLIC CRISIS: A PEEK IN THE MIND OF A HISTORY MAKER Armenia S.(1), De Angelis A.(2) (1) DIAG, Sapienza University of Rome, V.le Ariosto, 25 - 00185 Rome, Italy, - [email protected] President of the System Dynamics Italian Chapter (SYDIC) – www.systemdynamics.it (2) Col. It.A.F. – Teacher of Operations Planning - Joint Services Staff College of the Italian Armed Forces, Piazza della Rovere, 83, 00165 Rome, Italy - [email protected] ABSTRACT When studying history, it usually through the accounts of the achievements of some outstanding leaders, who were capable of grasping the defining elements of the complexity of situations they faced, like Julius Caesar, whose political career was a collection of successes that were the result of his deep understanding of the Roman society and of his sensitivity in appreciating the complex situations in the lands under his control. In this work we will focus on the early stages of Caesar’s campaign in the Gallic war. By a Systems Thinking approach, we will retrace Caesar’s thought process, thus showing that what Caesars faced in those years is no different from many situations that today’s policy makers are required to manage. It is striking to see how many similarities there are between then and now, and how many lessons could be learned (re-learned?) and applied by our policy makers. Caesar’s decisions and following actions were, in fact, the consequence of his deep and thorough understanding of the environment, and because of such systemic comprehension, he could achieve Rome’s desired end-state: securing the northwestern borders. -

Caesar De Bello Gallico

Caesar De Bello Gallico 1 Inhoudsopgave Levensloop ................................................................................................... 6 De Bello Gallico ............................................................................................ 9 onder het consulaat van .................................................................................... 12 Lucius Calpurnius Piso ....................................................................................... 12 Beschrijving van Gallia ....................................................................................... 14 De oorlog tegen de Helvetii ....................................................................... 21 caput 2 -29 ................................................................................................. 21 Oorlog met Ariovistus en de Germanen ........................................... 119 caput 30-54 ............................................................................................. 119 2 3 4 5 Inleiding. Levensloop Vanaf het eind van de 2e eeuw voor Chr. was het in Rome politiek onrustig. Steeds kwamen mannen, die machtswellustig waren. Die tendens zette zich in de eerste eeuw voor Chr. voort. In dit rijtje hoort ook Caesar. In Rome probeerden eind jaren 60 v. Chr. twee mannen van de volkspartij de macht tot zich te trekken: Crassus, een rijke handelsman en Caesar, een begaafd politicus. Crassus Pompeius Toen Pompeius, de grote generaal, terugkwam uit het oosten, waar hij de opstandige koning Mithridates mores had geleerd -

Julius Caesar's War Commentaries

Julius Caesar, Gallic Wars1 the Atrebates and the Veromandui, their neighbors, were there awaiting Julius Caesar was a Roman politician. He was elected consul in 59 the arrival of the Romans; for they had persuaded both these nations to BCE, and sent himself as the commander of a military expedition to try the same fortune of war [as themselves]: that the forces of the conquer Gaul (present-day France and Germany); he spend 58-51 BCE in Gaul and successfully conquered it, as well as Britain. His Aduatuci were also expected by them, and were on their march; that military success was helpful as a political asset against his rivals. He they had put their women, and those who through age appeared useless returned to Rome in 49 BCE and refused to disband his army; this led to civil war in which he successfully seized power. He was for war, in a place to which there was no approach for an army, on assassinated in 44 BCE. account of the marshes. The Gallic Wars was written by Julius Caesar himself (even though it refers to him in the third-person) and was published during [2.17]Having learned these things, he sends forward scouts and his lifetime, probably as a form of political self-promotion. The text centurions to choose a convenient place for the camp. And as a great seems to have been adapted from his original dispatches sent back to the Senate while the campaigns were going on.2 many of the surrounding Belgae and other Gauls, following Caesar, marched with him; some of these, as was afterwards learned from the Book 2 - (57 B.C.) prisoners, -

The Mystery of the Skeletons – the Clues 1

02-SHP History-Y7-Activities-cccc:Layout 1 13/8/08 09:20 Page 72 1A The mystery of the skeletons – the clues 1 72 SHP History Year 7 Teacher’s Resource Book © Hodder Education, 2008 02-SHP History-Y7-Activities-cccc:Layout 1 13/8/08 15:33 Page 73 1B The mystery of the skeletons – the clues 2 AB A Roman historian writing about the Britons (10BC–20AD) The Britons are war-mad, courageous and love fighting battles. They fight battles even if they have nothing on their side but their own strength and courage. C D ATREBATES BELGAE CANTIACI DUROTRIGES Maiden Castle II ON MN DU N 0 100 km E F The only written evidence about what happened around Maiden Castle is this, written by a Roman historian called Suetonius. He says Vespasian, the commander of the Second Legion, ‘fought 30 battles, conquered two warlike tribes and captured more than twenty large settlements’. © Hodder Education, 2008 SHP History Year 7 Teacher’s Resource Book 73 02-SHP History-Y7-Activities-cccc:Layout 1 13/8/08 09:20 Page 74 1C The mystery of the skeletons – the clues 3 GH I J The archaeologists at Maiden Castle Four of the people lived on for some uncovered 52 skeletons. There may be time after they were injured. We know more still buried, but only part of the this because the damaged bones had hillfort has been excavated. re-grown after the injury. Although we cannot tell exactly how long they lived ● Fourteen of the 52 skeletons had for after their injuries we know it must wounds made by weapons.