Making Sense of Shanghai's Growing Automobile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shanghai, China's Capital of Modernity

SHANGHAI, CHINA’S CAPITAL OF MODERNITY: THE PRODUCTION OF SPACE AND URBAN EXPERIENCE OF WORLD EXPO 2010 by GARY PUI FUNG WONG A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOHPY School of Government and Society Department of Political Science and International Studies The University of Birmingham February 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines Shanghai’s urbanisation by applying Henri Lefebvre’s theories of the production of space and everyday life. A review of Lefebvre’s theories indicates that each mode of production produces its own space. Capitalism is perpetuated by producing new space and commodifying everyday life. Applying Lefebvre’s regressive-progressive method as a methodological framework, this thesis periodises Shanghai’s history to the ‘semi-feudal, semi-colonial era’, ‘socialist reform era’ and ‘post-socialist reform era’. The Shanghai World Exposition 2010 was chosen as a case study to exemplify how urbanisation shaped urban experience. Empirical data was collected through semi-structured interviews. This thesis argues that Shanghai developed a ‘state-led/-participation mode of production’. -

Integrating Chinese and Western Pursuit of Excellence

2021 4th International Workshop on Advances in Social Sciences (IWASS 2021) Integrating Chinese and Western Pursuit of Excellence Jing Zeng1, Huijun Shen2 1Arts College of Sichuan University, PhD student 2College of Forestry, Sichuan Agricultural University, Wenjiang 611130, China Keywords: Shanghai furniture, Chinese and western combination, “innovation and progress” Abstract: “ShangHai furniture” was born under the combined effect of the localization of Western-style furniture and the westernization of faithful furniture. It is the most representative fusion of China and the West. This article analyzes the contribution of “Shanghai style furniture” to the fusion of Chinese and Western furniture and its positive effect on China's modern furniture innovation based on the four stages of “Shanghai style furniture”: “germination”, “development”, “rejuvenation” and “innovation”. 1. Introduction ShangHai furniture is the product of ShangHai culture, which generally refers to the combination of Chinese and Western style furniture. It is a combination of the advantages of Western-style furniture. During the Republic of China, the beach was born and the place where all the nations came together, thus forming this vast and profound furniture. Shanghai style furniture is the product of the collision between Chinese and Western cultures, and it is partially integrated, so it has dual characteristics of Chinese and Western cultures. Although it is ordinary daily necessities, it is the bearer of China's historical culture. Since ancient times, the Chinese nation has firmly believed in the idea of “harmony and difference” and “tolerance is greater”. Among the furniture, no one can better interpret the harmony culture than Shanghai furniture. Therefore, since its birth, it has become the spokesperson for the fusion of Chinese and Western furniture. -

Business Risk of Crime in China

Business and the Ris k of Crime in China Business and the Ris k of Crime in China Roderic Broadhurst John Bacon-Shone Brigitte Bouhours Thierry Bouhours assisted by Lee Kingwa ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 3 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Business and the risk of crime in China : the 2005-2006 China international crime against business survey / Roderic Broadhurst ... [et al.]. ISBN: 9781921862533 (pbk.) 9781921862540 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Crime--China--21st century--Costs. Commercial crimes--China--21st century--Costs. Other Authors/Contributors: Broadhurst, Roderic G. Dewey Number: 345.510268 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image: The gods of wealth enter the home from everywhere, wealth, treasures and peace beckon; designer unknown, 1993; (Landsberger Collection) International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Foreword . vii Lu Jianping Preface . ix Acronyms . xv Introduction . 1 1 . Background . 25 2 . Crime and its Control in China . 43 3 . ICBS Instrument, Methodology and Sample . 79 4 . Common Crimes against Business . 95 5 . Fraud, Bribery, Extortion and Other Crimes against Business . -

Shanghai Metro Map 7 3

January 2013 Shanghai Metro Map 7 3 Meilan Lake North Jiangyang Rd. 8 Tieli Rd. Luonan Xincun 1 Shiguang Rd. 6 11 Youyi Rd. Panguang Rd. 10 Nenjiang Rd. Fujin Rd. North Jiading Baoyang Rd. Gangcheng Rd. Liuhang Xinjiangwancheng West Youyi Rd. Xiangyin Rd. North Waigaoqiao West Jiading Shuichan Rd. Free Trade Zone Gucun Park East Yingao Rd. Bao’an Highway Huangxing Park Songbin Rd. Baiyin Rd. Hangjin Rd. Shanghai University Sanmen Rd. Anting East Changji Rd. Gongfu Xincun Zhanghuabang Jiading Middle Yanji Rd. Xincheng Jiangwan Stadium South Waigaoqiao 11 Nanchen Rd. Hulan Rd. Songfa Rd. Free Trade Zone Shanghai Shanghai Huangxing Rd. Automobile City Circuit Malu South Changjiang Rd. Wujiaochang Shangda Rd. Tonghe Xincun Zhouhai Rd. Nanxiang West Yingao Rd. Guoquan Rd. Jiangpu Rd. Changzhong Rd. Gongkang Rd. Taopu Xincun Jiangwan Town Wuzhou Avenue Penpu Xincun Tongji University Anshan Xincun Dachang Town Wuwei Rd. Dabaishu Dongjing Rd. Wenshui Rd. Siping Rd. Qilianshan Rd. Xingzhi Rd. Chifeng Rd. Shanghai Quyang Rd. Jufeng Rd. Liziyuan Dahuasan Rd. Circus World North Xizang Rd. Shanghai West Yanchang Rd. Youdian Xincun Railway Station Hongkou Xincun Rd. Football Wulian Rd. North Zhongxing Rd. Stadium Zhenru Zhongshan Rd. Langao Rd. Dongbaoxing Rd. Boxing Rd. Shanghai Linping Rd. Fengqiao Rd. Zhenping Rd. Zhongtan Rd. Railway Stn. Caoyang Rd. Hailun Rd. 4 Jinqiao Rd. Baoshan Rd. Changshou Rd. North Dalian Rd. Sichuan Rd. Hanzhong Rd. Yunshan Rd. Jinyun Rd. West Jinshajiang Rd. Fengzhuang Zhenbei Rd. Jinshajiang Rd. Longde Rd. Qufu Rd. Yangshupu Rd. Tiantong Rd. Deping Rd. 13 Changping Rd. Xinzha Rd. Pudong Beixinjing Jiangsu Rd. West Nanjing Rd. -

Shanghai Before Nationalism Yexiaoqing

East Asian History NUMBER 3 . JUNE 1992 THE CONTINUATION OF Papers on Fa r EasternHistory Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University Editor Geremie Barme Assistant Editor Helen 1.0 Editorial Board John Clark Igor de Rachewiltz Mark Elvin (Convenor) Helen Hardacre John Fincher Colin Jeffcott W.J.F. Jenner 1.0 Hui-min Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Michael Underdown Business Manager Marion Weeks Production Oahn Collins & Samson Rivers Design Maureen MacKenzie, Em Squared Typographic Design Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This is the second issue of EastAsian History in the series previously entitled Papers on Far Eastern History. The journal is published twice a year. Contributions to The Editor, EastAsian History Division of Pacific and Asian History, Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University, Canberra ACT 2600, Australia Phone +61-6-2493140 Fax +61-6-2571893 Subscription Enquiries Subscription Manager, East Asian History, at the above address Annual Subscription Rates Australia A$45 Overseas US$45 (for two issues) iii CONTENTS 1 Politics and Power in the Tokugawa Period Dani V. Botsman 33 Shanghai Before Nationalism YeXiaoqing 53 'The Luck of a Chinaman' : Images of the Chinese in Popular Australian Sayings Lachlan Strahan 77 The Interactionistic Epistemology ofChang Tung-sun Yap Key-chong 121 Deconstructing Japan' Amino Yoshthtko-translat ed by Gavan McCormack iv Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing ���Il/I, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover illustration Kazai*" -a punishment -

Virtual Shanghai

ASIA mmm i—^Zilll illi^—3 jsJ Lane ( Tail Sttjaca, New Uork SOif /iGf/vrs FO, LIN CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION Draper CHINA AND THE CHINESE L; THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 House 1918 WINE ATJD~SPIRIT MERCHANTS. PROVISION DEALERS. SHIP CHANDLERS. yigents for jfidn\iratty C/jarts- HOUSE BOATS supplied with every re- quisite for Up-Country Trips. LANE CRAWFORD 8 CO., LTD., NANKING ROAD, SHANGHAI. *>*N - HOME USE RULES e All Books subject to recall All borrowers must regis- ter in the library to borrow books fdr home use. All books must be re- turned at end of college year for inspection and repairs. Limited books must be returned within the four week limit and not renewed. Students must return all books before leaving town. Officers should arrange for ? the return of books wanted during their absence from town. Volumes of periodicals and of pamphlets are held in the library as much as possible. For special pur- poses they are given out for a limited time. Borrowers should not use their library privileges for the benefit of other persons Books of special value nd gift books," when the giver wishes it, are not allowed to circulate. Readers are asked to re- port all cases of books marked or mutilated. Do not deface books by marks and writing. - a 5^^KeservaToiioT^^ooni&^by mail or cable. <3. f?EYMANN, Manager, The Leading Hotel of North China. ^—-m——aaaa»f»ra^MS«»» C UniVerS"y Ubrary DS 796.S5°2D22 Sha ^mmmmilS«u,?,?llJff travellers and — — — — ; KELLY & WALSH, Ltd. -

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction The name Shanghai still conjures images of romance, mystery and adventure, but for decades it was an austere backwater. After the success of Mao Zedong's communist revolution in 1949, the authorities clamped down hard on Shanghai, castigating China's second city for its prewar status as a playground of gangsters and colonial adventurers. And so it was. In its heyday, the 1920s and '30s, cosmopolitan Shanghai was a dynamic melting pot for people, ideas and money from all over the planet. Business boomed, fortunes were made, and everything seemed possible. It was a time of breakneck industrial progress, swaggering confidence and smoky jazz venues. Thanks to economic reforms implemented in the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping, Shanghai's commercial potential has reemerged and is flourishing again. Stand today on the historic Bund and look across the Huangpu River. The soaring 1,614-ft/492-m Shanghai World Financial Center tower looms over the ambitious skyline of the Pudong financial district. Alongside it are other key landmarks: the glittering, 88- story Jinmao Building; the rocket-shaped Oriental Pearl TV Tower; and the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The 128-story Shanghai Tower is the tallest building in China (and, after the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the second-tallest in the world). Glass-and-steel skyscrapers reach for the clouds, Mercedes sedans cruise the neon-lit streets, luxury- brand boutiques stock all the stylish trappings available in New York, and the restaurant, bar and clubbing scene pulsates with an energy all its own. Perhaps more than any other city in Asia, Shanghai has the confidence and sheer determination to forge a glittering future as one of the world's most important commercial centers. -

Shanghai 2020

Deloitte China Research and Insight Centre Special issue, July 2010 Measuring Value® Shanghai 2020 Defining the challenge Secretary Yu Zhengsheng was quoted as saying Shanghai hosted two major events this June, a “Shanghai embraces advice and suggestions on meeting of the Shanghai International Financial how to grow better as a global financial center.” Advisory Committee and a Forum in Shanghai’s The goal itself and the openness of leaders financial center of Lujiazui on financial reform. to discussion of it are important to domestic Both events engaged Shanghai’s top Party and foreign business interests. The process will and government officials, all key Chinese accelerate changes as the city leaders identify financial regulators and a blue ribbon group of what Secretary Yu called “initiatives to break international business leaders. through the bottleneck that limits the city’s rise in the financial area.” (Shanghai Daily, 27 Jun 2010). Both events ultimately were about Shanghai’s goal to become a global financial center by 2020. This sharp assessment was echoed by Tu Guangshao, Shanghai’s deputy mayor in charge Both events demonstrated that Shanghai is serious of the city’s financial industry. Tu emphasised about this goal, and the leaders are looking far the need to open the city to more financial and wide to improve their understanding of the professionals, citing what he called a “severe best way to get there. Amidst some comments lack of experienced professionals in areas such as from the outside that China appears very financial technology and financial marketing.” satisfied - perhaps too satisfied - with what it has accomplished, throughout reforms and in the wake of the global financial crisis, Shanghai Party Global financial centers, today and tomorrow We see the convergence of these three The world is watching a series of meetings of the G8, G20 and other groups focused on the factors - a serious commitment to this architecture of a new global financial order and goal, admission of current regulatory framework. -

(Presentation): Improving Railway Technologies and Efficiency

RegionalConfidential EST Training CourseCustomizedat for UnitedLorem Ipsum Nations LLC University-Urban Railways Shanshan Li, Vice Country Director, ITDP China FebVersion 27, 2018 1.0 Improving Railway Technologies and Efficiency -Case of China China has been ramping up investment in inner-city mass transit project to alleviate congestion. Since the mid 2000s, the growth of rapid transit systems in Chinese cities has rapidly accelerated, with most of the world's new subway mileage in the past decade opening in China. The length of light rail and metro will be extended by 40 percent in the next two years, and Rapid Growth tripled by 2020 From 2009 to 2015, China built 87 mass transit rail lines, totaling 3100 km, in 25 cities at the cost of ¥988.6 billion. In 2017, some 43 smaller third-tier cities in China, have received approval to develop subway lines. By 2018, China will carry out 103 projects and build 2,000 km of new urban rail lines. Source: US funds Policy Support Policy 1 2 3 State Council’s 13th Five The Ministry of NRDC’s Subway Year Plan Transport’s 3-year Plan Development Plan Pilot In the plan, a transport white This plan for major The approval processes for paper titled "Development of transportation infrastructure cities to apply for building China's Transport" envisions a construction projects (2016- urban rail transit projects more sustainable transport 18) was launched in May 2016. were relaxed twice in 2013 system with priority focused The plan included a investment and in 2015, respectively. In on high-capacity public transit of 1.6 trillion yuan for urban 2016, the minimum particularly urban rail rail transit projects. -

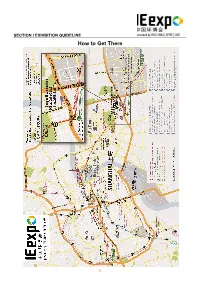

How to Get There

SECTION I EXHIBITION GUIDELINE How to Get There 12 SECTION I EXHIBITION GUIDELINE How to Get There (cont’d) Shanghai Metro Map 13 SECTION I EXHIBITION GUIDELINE How to Get There (cont’d) SNIEC is strategically located in Pudong‘s key economic development zone. There is a public traffic interchange for bus and metro, , one named “Longyang Road Station“ about 10-min walk from the station to fairground, and one named “Huamu Road Station“ about 1-min walk from the station to fairground. By flight The expo centre is located half way between Pudong International Airport and Hongqiao Airport, 35 km away from Pudong International Airport to the east, and 32 km away from Hongqiao Airport to the west. You can take the airport bus, maglev or metro directly to the expo center. From Pudong International Airport By taxi By Transrapid Maglev: from Pudong International Airport to Longyang Road Take metro line 2 to Longyang Road Station to change line 7 to Huamu Road Station, 60 min. By Airport Line Bus No. 3: from Pudong Int’l Airport to Longyang Road, 40 min, ca. RMB 20. From Hongqiao Airport By taxi Take metro line 2 to Longyang Road Station to change line 7 to Huamu Road Station, 60 min. By train From Shanghai Railway Station or Shanghai South Railway Station please take metro line1 to People’s Square, then take metro line 2 toward Pudong International Airport Station and get off at Longyang Road Station to change line7 to Huamu Road Station. From Hongqiao Railway Station, please take metro line 2 to Longyang Road Station and change line 7 to Huamu Road Station. -

Crime and Policing in Shanghai, Shenzhen and Xi'an

Appendix C. Media Sources Used in Chapter 2: Crime and policing in Shanghai, Shenzhen and Xi’an Asian Wall Street Journal 2004, ‘Shanghai tycoon draws three-year jail sentence’, Asian Wall Street Journal, 2 June. Barboza, David 2008, ‘Former party boss in China gets 18 years, The New York Times, 12 April. BBC Monitoring Service Asia Pacific 1994, ‘New police patrol system allows rapid response, “tight grip” on public order’, BBC Monitoring Service Asia Pacific, 7 March. BBC Monitoring Service Asia Pacific 1995, ‘Shanghai to fight economic crime by officials’,BBC Monitoring Service Asia Pacific, 20 January. BBC Monitoring Service Asia Pacific 1999, ‘Shanghai security chief reports move to accurate crime records’, BBC Monitoring Service Asia Pacific, 2 April. BBC Monitoring Service Asia Pacific 2003, ‘China: former Shenzhen Deputy Mayor Wang Ju faces corruption charges’, BBC Monitoring Service Asia Pacific, 6 November. BBC Monitoring Service Asia Pacific 2006, ‘Supermarkets in China’s Shenzhen receive bomb threats’, BBC Monitoring Service Asia Pacific, 18 January. Cao, Hai-dong 2004, ‘Xi’an founded the system of “outsourcing public security to individuals”’, Economy 2004(10), 2023. Chen, Hong 2006, ‘“Police bible” to upgrade security force’, China Daily, 20 February. Chen, Qide 1999, ‘Fight reduces crime rate: 12,900 criminals put in prison’, Shanghai Star, 5 February. Cheung, Agnes 1996, ‘Shenzhen anti-crime crusade’, South China Morning Post, 10 April. Chow, Chung-yan 2004, ‘More police promised as crime rate soars 57pc in Shenzhen’, South China Morning Post, 14 January, p. 1. 231 Business and the Risk of Crime in China Chow, Chung-yan 2005, ‘Police winning battle for Shenzhen streets’, South China Morning Post, 23 August, p. -

Global Chinese 2018; 4(2): 217–246

Global Chinese 2018; 4(2): 217–246 Don Snow*, Shen Senyao and Zhou Xiayun A short history of written Wu, Part II: Written Shanghainese https://doi.org/10.1515/glochi-2018-0011 Abstract: The recent publication of the novel Magnificent Flowers (Fan Hua 繁花) has attracted attention not only because of critical acclaim and market success, but also because of its use of Shanghainese. While Magnificent Flowers is the most notable recent book to make substantial use of Shanghainese, it is not alone, and the recent increase in the number of books that are written partially or even entirely in Shanghainese raises the question of whether written Shanghainese may develop a role in Chinese print culture, especially that of Shanghai and the surrounding region, similar to that attained by written Cantonese in and around Hong Kong. This study examines the history of written Shanghainese in print culture. Growing out of the older written Suzhounese tradition, during the early decades of the twentieth century a distinctly Shanghainese form of written Wu emerged in the print culture of Shanghai, and Shanghainese continued to play a role in Shanghai’s print culture through the twentieth century, albeit quite a modest one. In the first decade of the twenty-first century Shanghainese began to receive increased public attention and to play a greater role in Shanghai media, and since 2009 there has been an increase in the number of books and other kinds of texts that use Shanghainese and also the degree to which they use it. This study argues that in important ways this phenomenon does parallel the growing role played by written Cantonese in Hong Kong, but that it also differs in several critical regards.