Editor in Chief: Nikos Passas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Office of the Attorney -General

OFFICE- OF THE,, ATTORNEY- - ---- -GENERAL I -- ' . Department of Law , . - I - Fi~cal ,Year 1993 Annual Report Grant Woods - -A!torney Genera_} Grant Woods Attorney General Robert B. Carey J.M. Howard First Assistant Attorney General Special Counsel Civil Division · Criminal Division H. Leslie Hall Michael C. Cudahy Chief Counsel Chief Counsel Human Services Division Management Services Cecil B. Patterson Thomas G. Augherton Chief Counsel Chief of Administration TRANSMITTAL LETTER STATE OF ARIZONA OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL GRANT WOODS MAIN PHONE: 542-5025 ATTORNEY GENERAL 1275 WEST WASHINGTON, PHOENIX 85007-2926 TELECOPIER : 542-4085 November 5, 1993 The Honorable J. Fife Symington Governor of Arizona State Capitol, Executive Tower 1700 W. Washington Phoenix, Arizona 85007 Dear Governor Symington: I am pleased to submit to you the annual report of the Office of the Attorney General, as required by ARS § 41-194(B). During the past fiscal . year, this administration continued its focus of protecting Arizona's citizens through aggressive enforcement of state laws and providing quality legal representation to state agencies. We have vigorously defended Arizona's environment by prosecuting those that destroy our natural resources, pursued dozens of companies and individuals who prey on unsuspecting consumers, and convicted many notorious criminals for the heinous crimes they perpetrated. We concentrated our administrative efforts into implementing cost-saving measures that allow us to prioritize our resources into retaining and compensating top-quality \egal staff. Loss of well-trained, experienced attorneys from the Attorney General's Office to higher paying private and public sector positions continues to be a problem that requires close scrutiny by the Legislature. -

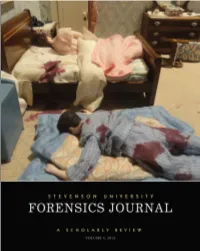

The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death Stephanie Witt

School of Graduate and Professional Studies 100 Campus Circle, Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 1-877-468-6852 accelerate.stevenson.edu STEVENSON UNIVERSITY FORENSICS JOURNAL VOLUME 4 EDITORIAL BOARD EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Carolyn Hess Johnson, Esq. PUBLISHER Carolyn Hess Johnson, Esq. EDITORS Abigail Howell Stephanie Witt COVER PHOTO Bruce Goldfarb Assistant to the Chief Medical Examiner, Maryland DESIGN & LAYOUT Chip Burkey Cassandra Bates Stevenson University Marketing and Public Relations Office Copyright © 2013, author(s) and Stevenson University Forensics Journal. No permission is given to copy, distribute or reproduce this article in any format without prior explicit written permission from the article’s author(s) who hold exclusive rights to impose usage fee or royalties. FORENSICS JOURNAL Welcome to our fourth annual Stevenson University Forensics Journal. This year, as always, we bring fresh voices and perspectives from all aspects and areas of the field. I am pleased to note that a new section has been added this year, highlighting the process of library research in the vast field of Forensic Studies. Our Stevenson University librarians bring the research pro- cess into the twenty-first century by showcasing a variety of on-line resources available to researchers. Also of note is the connection between our cover photo and the interview conducted with Dr. David Fowler, Chief Medical Examiner for the State of Maryland. Assistant Editor Stephanie Witt joins the Journal as a contributor to explain the fascinating Nutshell Series of Unexplained Deaths. We are privileged this year to have the Honorable Lynne A. Battaglia providing her insights into the Court’s perspective on the prominent role of forensic evidence in modern litigation. -

Cyber Romance Scam Victimization Analysis Using Routine Activity Theory Versus Apriori Algorithm

(IJACSA) International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, Vol. 9, No. 12, 2018 Cyber Romance Scam Victimization Analysis using Routine Activity Theory Versus Apriori Algorithm Mohd Ezri Saad1 Siti Norul Huda Sheikh Abdullah2, Mohd Zamri Murah3 Commercial Crime Investigation Department Center for Cyber Security Faculty of Information Royal Malaysia Police, Bukit Aman Science and Technology Bangi, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Selangor, Malaysia Abstract—The advance new digital era nowadays has led to These cyber romance scams has fraud Australians out of the increasing cases of cyber romance scam in Malaysia. These millions every years [1], [5]. No exception to Malaysia that technologies have offered both opportunities and challenge, has been the top 6 countries that recorded highest number of depending on the purpose of the user. To face this challenge, the cybercrime cases, with total loses reaching RM1 billion key factors that influence the susceptibility to cyber romance (Source: Bernama Report in 2014). Other countries like scam need to be identified. Therefore, this study proposed cyber Taiwan, China, Thailand, Indonesia and Hong Kong also were romance scam models using statistical method and Apriori listed together. While, Sophos Threat Report in 2014 stated techniques to explore the key factors of cyber romance scam that cybercrime attacks have been increased in the first quarter victimization based on the real police report lodged by the of 2014 and 81% of them happened in Malaysia. This victims. The relationship between demographic variables such as phenomenon was in line with the rapid growth of Malaysia's age, education level, marital status, monthly income and independent variables such as level of computer skills and the digital economy [6]. -

Pizzagate / Pedogate, a No-Nonsense Fact-Filled Reader

Pizzagate / Pedogate A No-nonsense Fact-filled reader Preface I therefore determine that serious human rights abuse and corruption around the world constitute an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States, and I hereby declare a national emergency to deal with that threat. —Trump Executive Order 13818, Dec. 20, 2017 Pizzagate means many things to many people, the angle of the lens may be different, but the focus zeros in on a common body of incontestable facts. The fruit of top researchers collected in this reader allows you to compare, correlate and derive a flexible synthesis to suit your needs. An era of wild contradiction is upon us in the press. The psychopathic rumblings that pass for political discourse bring the artform of infotainment to a golden blossoming. A bookstore display table featuring The Fixers; The Bottom-Feeders, Crooked Lawyers, Gossipmongers, and Porn Stars Who Created the 45th President versus Witch Hunt; The Story of the Greatest Mass Delusion in American Political History are both talking about the same man, someone who paid for his campaign out of his own pocket. There were no big donors from China and the traditional bank of puppeteers. This created a HUGE problem, one whose solution threatened the money holders and influence peddlers. New leadership and a presidential order that threw down the gauntlet, a state of emergency, seeded the storm clouds. The starting gun was fired, all systems were go, the race had begun. FISAs and covert operations sprang into action. The envelopes are being delivered, the career decisions are being made, should I move on or stay the course. -

Office of the Attorney General

OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL Department of La,w Fiscal Year 1992 Annual Report Grant Woods Attorney General Grant Woods Attorney General Robert B. Carey First Assistant Attorney General Civil Division Crimin al Divi sion J M. Howard Michael C. Cudahy Chi ef Counsel Chief Counsel Human Services Division Management Services Cecil B. Patterson, Jr. Thomas G. Augherton Chief Counsel Chief of Administration Transmittal Letter OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL GRANT WOOD S MAIN PHONE : 542-5025 ATTORNEY GENERAL 1275 WEST WASHINGTON, PHOENIX 85007 TELECOPIER : 542-4085 October 15, 1992 The Honorable J. Fife Symington Governor of Arizona State Capitol, Executive Tower 1700 W. Washington Phoenix, Arizona 85007 Dear Governor Symington: I am pleased to submit to you the annual report of the Office of the Arizona Attorney General, as required by ARS § 41-194.B. These are difficult financial times for Arizona Government, and I appreciate the support offered by your office and members of the Arizona Legislature to ensure thoughtful funding decisions regarding the Law Department's budget. · I can assure you the men and women of the Attorney General's Office, attorneys and support staff alike, are committed to serving the continuing needs of our state client agencies as well as the needs of all Arizonans. During the past fiscal year, this administration continued to focus on increased civil rights protection for the citizens of our state and continued aggressive education and protection of consumers. The Arizona Legislature's passage of the equivalent legislation to the federal Americans With Disabilities Act, following the previous session's passage of the federally equivalent Fair Housing Act, has proven Arizona to be a leader in enacting in1portant civil rights protections for its citizens. -

ONLINE DATING SERVICES. Emerging Consumer Law Issues

LAURA RODRIGUEZ RENGIFO ONLINE DATING SERVICES. Emerging consumer law issues. LLM RESEARCH PAPER LAWS 532: CONSUMER LAW FACULTY OF LAW 2015 2 Contents I. ABSTRACT. ............................................................................................................................ 3 Word length 3 II. INTRODUCTION. ................................................................................................................... 4 III. AN INSIGHT IN THE ODS CURRENT PARADIGM. ......................................................... 5 IV. THE ROMANCE SCAMS. ................................................................................................... 7 A ODS Users are Vulnerable Consumers: The perfect target for scammers. .............................. 9 IMAGE 1. .................................................................................................................................... 10 1 The concept of “Vulnerable Consumers” and its implications. ................................................ 11 IMAGE 2. .................................................................................................................................... 14 B Recommendations about how to address Romance Scam And ODS user vulnerability: ....... 14 V. ISSUES THAT ARISE FROM THE ODS “TERMS AND CONDITIONS”. ....................... 18 A.ODS Privacy concerns. ............................................................................................................ 19 B Spam and unwanted messages. ............................................................................................... -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

An Investigation of Fraud in Nonprofit Organizations: Occurrences and Deterrents

An Investigation of Fraud in Nonprofit Organizations: Occurrences and Deterrents by Janet Greenlee, Mary Fischer Teresa Gordon,* and Elizabeth Keating The Hauser Center for Nonprofit Organizations Harvard University December 2006 Working Paper No. 35 * Corresponding author – Teresa Gordon, Professor of Accounting, University of Idaho, College of Business & Economics, P O Box 443161, Moscow, ID 83844-3161, Tel: (208) 885-8960, Fax: (208) 885-6296, E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners for permitting the use of their proprietary data in this paper. Brief Biographies for Authors (As of June 28, 2006 and subject to revision/up-dating: one author is out of country) Janet Greenlee, CPA, is Associate Professor of Accounting at the University of Dayton in Ohio. She received her PhD in Accounting from the University of Kentucky, her MBA from UCLA and her MSW from West Virginia University. Mary Fischer, CGFM, is professor of accounting at the University of Texas at Tyler. She received her PhD from the University of Connecticut. She is past-president of the Government and Nonprofit Section of the American Accounting Association. Teresa P. Gordon, CPA, is professor of accounting at the University of Idaho. She received her PhD from University of Houston. She is currently a member of the Accounting Principles Council of the National Association of College and University Business Officers. Elizabeth K. Keating, CPA, is the Eli Goldston Lecturer on Law at Harvard Law School and a Senior Research Fellow Assistant at the Hauser Center for Nonprofit Organizations. She received her PhD in management from the Sloan School of Management at MIT and her MBA from the Stern School of Business at New York University. -

Romance Scams Spotlight

Romance scams take record dollars in 2020 They say love hurts. With romance scams that’s obvious reason may be the pandemic limiting our doubly true – hearts are broken and wallets are ability to meet in person. But outside the pandemic, emptied. For three years running, people have reported the share of people who have ever used an online losing more money on romance scams than on any dating site or app has also been rising.3 And romance other fraud type identified in Sentinel.1 In 2020, scammers are primed to take advantage. Scammers reported losses to romance scams reached a record fabricate attractive online profiles to draw people in, $304 million, up about 50% from 2019. For an often lifting pictures from the web and using made up individual, that meant a median dollar loss of $2,500. names. Some go a step further and assume the From 2016 to 2020, reported total dollar losses identities of real people. Once they make online increased more than fourfold, and the number of contact, they make up reasons not to meet in person. reports nearly tripled.2 The pandemic has both made that easier and inspired new twists to their stories, with many people reporting It is reasonable to wonder: what happened in 2020 to that their so-called suitor claimed to be unable to make these dollars losses continue to spike? An travel because of the pandemic. Some scammers have Consumer Protection Data Spotlight | February 2021 1 reportedly even canceled first date plans due to a the card’s PIN number to the scammer. -

Tackling Fraud in the Charity Sector a Summary of Conference Proceedings

Tackling fraud in the charity sector A summary of conference proceedings Making your money count SUPPORTED BY This guide is for trustees and senior managers of charities in England and Wales as well as their professional advisors. It highlights the main learning points from the first national conference on charity fraud held in late 2015, and provides signposts to extra sources of information, support and best practice. It concludes with a summary of top tips for preventing, detecting and responding to fraud. ABOUT THE ORGANISERS Charity Commission The Charity Commission registers and regulates charities in England and Wales. It ensures that charities meet their legal requirements and provides guidance to help them run themselves as effectively as possible while preventing abuse (including fraud). gov.uk/government/organisations/charity-commission Fraud Advisory Panel The Fraud Advisory Panel is an independent voice of the anti- fraud community. It champions anti-fraud best practice and works to improve fraud awareness, understanding and resilience. fraudadvisorypanel.org Published February 2016 © Fraud Advisory Panel 2016 All rights reserved. If you want to reproduce or redistribute any of the material in this publication you should first get the Fraud Advisory Panel’s permission in writing. Laws and regulations referred to in this Fraud Advisory Panel publication are stated as at 1 February 2016. Every effort has been made to make sure the information it contains is accurate at the time of creation. The Fraud Advisory Panel cannot guarantee the completeness or accuracy of the information in this publication and shall not be responsible for errors or inaccuracies. -

Romance Scams Rank Number One on Total Reported Losses

Romance scams rank number one on total reported losses People looking for romance are hoping to be swept off need help with travel costs for a long-awaited visit is their feet, not caught up in a scam. But tens of another common ruse. thousands of reports in Consumer Sentinel show that a scam is what many people find. In 2018, Sentinel had Scammers can reap large rewards for time spent more than 21,000 reports about romance scams, and courting their targets. The median individual loss to a people reported losing a total of $143 million – that’s romance scam reported in 2018 was $2,600, about more than any other consumer fraud type identified in seven times higher than the median loss across all Sentinel.1 These reports are rising steadily. In 2015, by other fraud types.2 People often reported sending comparison, people filed 8,500 Sentinel reports with money repeatedly for one supposed crisis after dollar losses of $33 million. another. Romance scammers lure people with phony online profiles, often lifting photos from the web to create attractive and convincing personas. They might make up names or assume the identities of real people. Reports indicate the scammers are active on dating apps, but also on social media sites that aren’t generally used for dating. For example, many people say the scam started with a Facebook message. Once these fraudsters have people by the heartstrings, they say they need money, often for a medical People who said they were ages 40 to 69 reported emergency or some other misfortune. -

Fighting Fraud: Senate Aging Committee Identifies Top 10 Scams Targeting Our Nation’S Seniors

United States Senate Special Committee on Aging Fighting Fraud: Senate Aging Committee Identifies Top 10 Scams Targeting Our Nation’s Seniors Senator Susan M. Collins (R-ME), Chairman Senator Robert P. Casey, Jr. (D-PA), Ranking Member Tips from the United States Senate Special Committee on Aging for Avoiding Scams • Con artists force you to make decisions fast and may threaten you. • Con artists disguise their real numbers, using fake caller IDs. • Con artists sometimes pretend to be the government (e.g. IRS). • Con artists try to get you to provide them personal information like your Social Security number or account numbers. • Before giving out your credit card number or money, please ask a friend or family member about it. • Beware of offers of free travel! If you receive a suspicious call, hang up and please call the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging’s Fraud Hotline at 1-855-303-9470 Note: This document has been printed for information purposes. It does not represent either findings or recommendations formally adopted by the Committee. Protecting Older Americans Against Fraud Unitedi d SSStates Senate SiSpeciall CommitteeCi on Aging i Table of Contents Dear Friends ...........................................................................................................................................3 Top 10 Most-Reported Scams ................................................................................................................4 Abbreviations ..........................................................................................................................................6