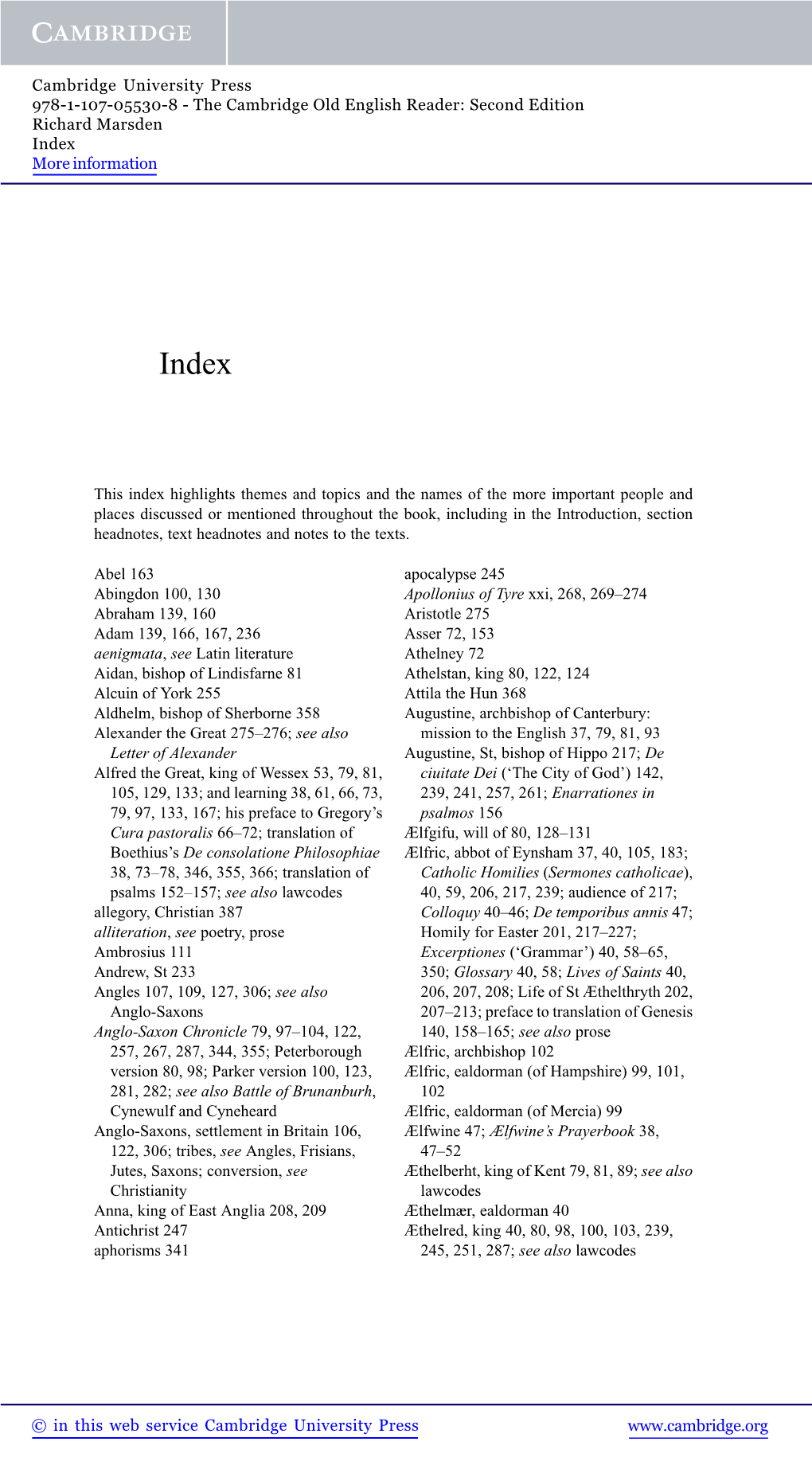

This Index Highlights Themes and Topics and the Names of the More

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Vikings Chapter

Unit 1 The European and Mediterranean world The Vikings In the late 8th century CE, Norse people (those from the North) began an era of raids and violence. For the next 200 years, these sea voyagers were feared by people beyond their Scandinavian homelands as erce plunderers who made lightning raids in warships. Monasteries and towns were ransacked, and countless people were killed or taken prisoner. This behaviour earned Norse people the title Vikingr, most probably meaning ‘pirate’ in early Scandinavian languages. By around 1000 CE, however, Vikings began settling in many of the places they had formerly raided. Some Viking leaders were given areas of land by foreign rulers in exchange for promises to stop the raids. Around this time, most Vikings stopped worshipping Norse gods and became Christians. 9A 9B How was Viking society What developments led to organised? Viking expansion? 1 Viking men spent much of their time away from 1 Before the 8th century the Vikings only ventured home, raiding towns and villages in foreign outside their homelands in order to trade. From the lands. How do you think this might have affected late 8th century onwards, however, they changed women’s roles within Viking society? from honest traders into violent raiders. What do you think may have motivated the Vikings to change in this way? 226 oxford big ideas humanities 8 victorian curriculum 09_OBI_HUMS8_VIC_07370_TXT_SI.indd 226 22/09/2016 8:43 am chapter Source 1 A Viking helmet 9 9C What developments led to How did Viking conquests Viking expansion? change societies? 1 Before the 8th century the Vikings only ventured 1 Christian monks, who were often the target of Viking outside their homelands in order to trade. -

Romsey Abbey

A S H O RT ACCO UN T OF ROMSEY AB B EY . A D ESCRI PTI ON OF T H E FAB RI C ‘ AN D NOT E S ON T H E H I STO RY OF T H E V MARY CON ENT OF S S . ET H E LF LED A -“V [A r BY THE RE V. T . PE RKINS R OF N R SE R E CTO TU R WO TH , DOR T “ ” ” “ A EN S E N B N E AUTHOR OF M I , ROU , WIM OR ” A N D S E T C. CHRI TCHURCH , W I TH $ $$I I ILLUS TRATIONS LONDON GEORGE BE L L AND S ONS 1 9 07 O CH ’S WI CK PRESS : CHARLES WHITTI N GHAM AN D CO v Q . ‘ s l O KS R N N N D N . O COU T , CHA CERY LA E , LO O P R E F ACE I T H E architecturaland descriptive part of this book is the result of a of careful personal examination the f bric, made when the author has visited the abbey at various times during the last twenty years . The illustrations are reproduced from photo of graphs taken by him on the occasions these visits . The historical information has been derived from many “ sources . Among these may especially be mentioned An Essay ” C . descriptive of the Abbey Church of Romsey, by Spence, the first edition of which was published in 1 85 1 ; the small ofiicial guide sold in the church , and Records of Romsey m Abbey, compiled from anuscript and printed records, by . -

Nonhuman Voices in Anglo-Saxon Literature and Material Culture

James Paz - 9781526115997 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 10/04/2021 03:02:37AM via free access i NONHUMAN VOICES IN ANGLO- SAXON LITERATURE AND MATERIAL CULTURE James Paz - 9781526115997 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 10/04/2021 03:02:37AM via free access ii Series editors: Anke Bernau and David Matthews Series founded by: J. J. Anderson and Gail Ashton Advisory board: Ruth Evans, Nicola McDonald, Andrew James Johnston, Sarah Salih, Larry Scanlon and Stephanie Trigg The Manchester Medieval Literature and Culture series publishes new research, informed by current critical methodologies, on the literary cultures of medieval Britain (including Anglo- Norman, Anglo- Latin and Celtic writings), including post- medieval engagements with and representations of the Middle Ages (medievalism). ‘Literature’ is viewed in a broad and inclusive sense, embracing imaginative, historical, political, scientific, dramatic and religious writings. The series offers monographs and essay collections, as well as editions and translations of texts. Titles Available in the Series The Parlement of Foulys (by Geoffrey Chaucer) D. S. Brewer (ed.) Language and imagination in the Gawain- poems J. J. Anderson Water and fire:The myth of the Flood in Anglo- Saxon England Daniel Anlezark Greenery: Ecocritical readings of late medieval English literature Gillian Rudd Sanctity and pornography in medieval culture:On the verge Bill Burgwinkle and Cary Howie In strange countries: Middle English literature and its afterlife: Essays in Memory of J. J. Anderson David -

Early Mercian Text Production: Authors, Dialects, and Reputations

Early Mercian Text Production: Authors, Dialects, and Reputations Abstract There are suggestions that King Alfred’s legendary literary renaissance may have been a reaction to the efforts of the neighbouring kingdom of Mercia. According to Asser, Alfred assembled a group of literary scholars from this rival Mercian tradition at his court. But it is not clear what early literary activities these scholars could have been involved in to justify their pre-Alfredian reputation. This article tries to outline the historical and literary evidence for early Mercian text production, and the importance of this ‘other’ early literary corpus. What is our current knowledge of Mercian text production and the political and literary relationship of Mercia with Canterbury? What was the relationship of Alfred’s educational movement with its Mercian forerunner? Why is modern scholarship better informed about Alfred’s movement than any Mercian rival culture? If our current knowledge of this area is insufficient for the writing of a literary history of Mercia, a provisional list of texts and bibliography, published electronically for convenient updating, may prove useful in the meantime. Alfredian evidence for Mercian literary culture That King Alfred claims to have initiated an educational Renaissance is well known. Alfredian writings acknowledge a marked decline in learning and scholarship, at least in terms of Latin text composition and manuscript production, and at least in Wessex (Lapidge 1996, 436-439). But the same texts also suggest the existence of -

Student-Centered, Interactive Teaching of the Anglo-Saxon Cult of the Cross Christopher R

English Faculty Publications English Fall 2014 Student-Centered, Interactive Teaching of the Anglo-Saxon Cult of the Cross Christopher R. Fee Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/engfac Part of the Educational Methods Commons, European History Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Fee, Christopher. "Student-Centered, Interactive Teaching of the Anglo-Saxon Cult of the Cross." Old English Newsletter 45.3 (Fall 2014). This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/engfac/51 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Student-Centered, Interactive Teaching of the Anglo-Saxon Cult of the Cross Abstract Although most Anglo-Saxonists deal with Old English texts and contexts as a matter of course in our research agendas, many of us teach relatively few specialized courses focused on our areas of expertise to highly-trained students; thus, many Old English texts and objects which are commonplace in our research lives can seem arcane and esoteric to a great many of our students. This article proposes to confront this gap, to suggest some ways of teaching a few potentially obscure texts and artifacts to undergrads, to offer some guidance about uses of technology in this endeavor, and to help fellow teachers of undergraduate Old English to develop ways to impart some transferable skills and modes of critical thinking to unsuspecting students. -

The Textin the Community

The in the Text Community Essays on Medieval Works, Manuscripts, Authors, and Readers edited by jill mann & maura nolan University of Notre Dame Press Q Notre Dame, Indiana Copyright © 2006 by University of Notre Dame Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 www.undpress.nd.edu All Rights Reserved Designed by Jane Oslislo Set in 9.9/13.8 Janson by Four Star Books Printed in Hong Kong by Kings Time Printing Press, Ltd. Library of Congress Cataloging in-Publication Data The text in the community : essays on medieval works, manuscripts, authors, and readers / edited by Jill Mann and Maura Nolan. p. cm. Includes index. isbn 0-268-03495-8 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 0-268-03496-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Literature, Medieval—History and criticism. 2. Manuscripts, Medieval—History. I. Mann, Jill. II. Nolan, Maura. pn671.t38 2006 809'.02—dc22 2005035128 ∞This book is printed on acid-free paper. contents List of Illustrations vii List of Contributors xi Abbreviations List xiii Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 maura nolan 1 Versifying the Bible in the Middle Ages 11 michael lapidge 2 “He Knew Nat Catoun”: Medieval School-Texts and Middle English Literature 41 jill mann 3 Computing Cynewulf: The Judith-Connection 75 andy orchard Q vi R Contents 4 The Contexts of Notre Dame 67 107 a.s.g. edwards 5 The Haunted Text: Ghostly Reflections in A Mirror to Devout People 129 vincent gillespie 6 The Visual Environment of Carthusian Texts: Decoration and Illustration in Notre Dame 67 173 jessica brantley 7 The Knight and the Rose: French Manuscripts in the Notre Dame Library 217 maureen boulton 8 The Meditations on the Life of Christ: An Illuminated Fourteenth-Century Italian Manuscript at the University of Notre Dame 237 dianne phillips Index of Manuscripts 283 General Index 287 list of illustrations plate 1. -

The Intertextuality of Beowulf, Cynewulf and Andreas1

The departure of the hero in a ship: The intertextuality of Beowulf , Cynewulf and Andreas 1 Francis Leneghan University of Oxford This article identifies a new Old English poetic motif, ‘The Departure of the Hero in a Ship’, and discusses the implications of its presence in Beowulf , the signed poems of Cynewulf and Andreas , a group of texts already linked by shared lexis, imagery and themes. It argues that the Beowulf -poet used this motif to frame his work, foregrounding the question of royal succession. Cynewulf and the Andreas -poet then adapted this Beowulfian motif in a knowing and allusive manner for a new purpose: to glorify the church and to condemn its enemies. Investigation of this motif provides further evidence for the intertextuality of these works. Keywords : Old English poetry; Beowulf , Cynewulf; Andreas ; Anglo-Saxon literature 1. Introduction Scholars have identified a number of ‘motifs’, ‘themes’ or ‘type scenes’ in Old English poetry. Two of the best-known such motifs are ‘the beasts of battle’, typically featuring the carrion eagle, wolf and raven, anticipating or rejoicing in slaughter (Magoun 1955, Bonjour 1957, Griffith 1993), and ‘the hero on the beach’, wherein a hero is depicted with his retainers in the presence of a flashing light, as a sea-journey is completed (or begun), usually at dawn 1 I would like to thank Daniel Anlezark, Hugh Magennis, Richard North, Andy Orchard, Rafael Pascual and Daniel Thomas for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this article. Francis Leneghan, Selim24 (2019): 105 –132. ISSN 1132-631X / DOI https://doi.org/10.17811/selim.24.2019.105-134 106 Francis Leneghan (Crowne 1960: 368; Fry 1966, 1971).2 Broadening the focus to consider both Old English verse and prose, Mercedes Salvador Bello identified the ‘leitmotif’ of ‘the arrival of the hero in a ship’ in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and Beowulf , featuring “a recurrent thematic pattern which presents the story of the heroes (or the hero) who arrive from northern lands in a boat and become the ancestors of Anglo-Saxon dynasties” (1998: 214). -

Redeeming Beowulf and Byrhtnoth

Redeeming Beowulf: The Heroic Idiom as Marker of Quality in Old English Poetry Abstract: Although it has been fashionable lately to read Old English poetry as being critical of the values of heroic culture, the heroic idiom is the main, and perhaps the only, marker of quality in Old English poetry. Considering in turn the ‘sacred heroic’ in Genesis A and Andreas, the ‘mock heroic’ in Judith and Riddle 51, and the fiercely debated status of Byrhtnoth and Beowulf in The Battle of Maldon and Beowulf, this discussion suggests that modern scholarship has confused the measure with the measured. Although an uncritical heroic idiom may not be to modern critical tastes, it is suggested here that the variety of ways in which the heroic idiom is used to evaluate and mark value demonstrates the flexibility and depth of insight achieved by Old English poets through their apparently limited subject matter. A hero can only be defined by a narrative in which he or she meets or exceeds measures set by society—in which he or she demonstrates his or her quality. In that sense, all heroic narratives are narratives about quality. In Old English poetry, the heroic idiom stands as the marker of quality for a wide range of things: people, artefacts, actions, and events that are good, respected, desirable, and valued are marked by being presented with the characteristic language and ethic of an idealised, archaic warrior-culture.1 This is not, of course, a new point; it is traditional in Old English scholarship to associate quality with the elite, military world of generous war-lords, loyal thegns, gorgeous equipment, great acts of courage, and 1 The characteristic subject matter and style of Old English poetry is referred to in varying ways by critics. -

By Stuart Hill

by Stuart Hill BACKGROUND The Anglo-Saxons settled in Britain from around 410AD. They originally formed many kingdoms which were led by individual leaders. Eventually, the Anglo-Saxons came together as one country ruled by one leader. Athelstan was crowned king of the Saxons in 925AD but didn’t become ‘King of the English’ until 927AD. The Battle of Brunanburh in 937AD was his greatest victory and confirmed England as an Anglo-Saxon kingdom. He was viewed as a great politician and a courageous soldier who was reported as never having lost a battle. Like many other Saxon leaders, much of his reign was spent fighting Danish invaders and other rebellions for control of the country. One of Athelstan’s greatest achievements was to unite England and to establish the boundaries of England, Scotland and Wales that still remain today. He also strengthened the laws of the country and established burhs (fortified towns) where trade could flourish. He could be described as ‘The First King of England’. (For more information see the historical note written by the author on pages 180-181.) EXPLORING THE BOOK – READING FOR DISCUSSION PROLOGUE 1. How does the prologue give the reader a clue as to what might happen in the story? 2. Why has the author included a prologue? CHAPTER I 1. The story is written in the first person from the perspective of Edwin. How would the first chapter change if it was written in the third person? Why do you think the author chose to use the first person? 2. Why does Edwin think he is lucky? 3. -

Rędende Iudithše: the Heroic, Mythological and Christian Elements in the Old English Poem Judith

University of San Diego Digital USD Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses and Dissertations Fall 12-22-2015 Rædende Iudithðe: The eH roic, Mythological and Christian Elements in the Old English Poem Judith Judith Caywood Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/honors_theses Part of the European Languages and Societies Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Digital USD Citation Caywood, Judith, "Rædende Iudithðe: The eH roic, Mythological and Christian Elements in the Old English Poem Judith" (2015). Undergraduate Honors Theses. 15. https://digital.sandiego.edu/honors_theses/15 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rædende Iudithðe: The Heroic, Mythological and Christian Elements in the Old English Poem Judith ______________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty and the Honors Program Of the University of San Diego ______________________ By Jude Caywood Interdisciplinary Humanities 2015 Caywood 2 Judith is a character born from the complex multicultural forces that shaped Anglo-Saxon society, existing liminally between the mythological, the heroic and the Christian. Simultaneously Germanic warrior, pagan demi-goddess or supernatural figure, and Christian saint, Judith arbitrates amongst the seemingly incompatible forces that shaped the poet’s world, allowing the poem to serve as an important site for the making of a new Anglo-Saxon identity, one which would eventually come to be the united English identity. She becomes a single figure who is able to reconcile these opposing forces within herself and thereby does important cultural work for the world for which the poem was written. -

Animality, Subjectivity, and Society in Anglo-Saxon England

IDENTIFYING WITH THE BEAST: ANIMALITY, SUBJECTIVITY, AND SOCIETY IN ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of English Language and Literature by Matthew E. Spears January 2017 © 2017 Matthew E. Spears IDENTIFYING WITH THE BEAST: ANIMALITY, SUBJECTIVITY, AND SOCIETY IN ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND Matthew E. Spears, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2017 My dissertation reconsiders the formation of subjectivity in Anglo-Saxon England. It argues that the Anglo-Saxons used crossings of the human-animal divide to construct the subject and the performance of a social role. While the Anglo-Saxons defined the “human” as a form of life distinct from and superior to all other earthly creatures, they also considered most humans to be subjects-in-process, flawed, sinful beings in constant need of attention. The most exceptional humans had to be taught to interact with animals in ways that guarded the self and the community against sin, but the most loathsome acted like beasts in ways that endangered society. This blurring of the human-animal divide was therefore taxonomic, a move to naturalize human difference, elevate some members of society while excluding others from the community, and police the unruly and transgressive body. The discourse of species allowed Anglo-Saxon thinkers to depict these moves as inscribed into the workings of the natural world, ordained by the perfect design of God rather than a product of human artifice and thus fallible. “Identifying with the Beast” is informed by posthumanist theories of identity, which reject traditional notions of a unified, autonomous self and instead view subjectivity as fluid and creative, produced in the interaction of humans, animals, objects, and the environment. -

Alfred the Great and the Pursuit of Wisdom in Anglo-Saxon Spirituality

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Wisdom’s Missionary: Alfred the Great and the Pursuit of Wisdom in Anglo-Saxon Spirituality A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of the Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By James Andrew Estes Washington, DC 2016 Wisdom’s Missionary: Alfred the Great and the Pursuit of Wisdom in Anglo-Saxon Spirituality James Andrew Estes, PhD Director: Joshua Benson, PhD Co-Director: Lilla Kopár, PhD Abstract Alfred, King of Wessex (r. 871-899), is commonly studied as a military, political, and educational leader and reformer in Anglo-Saxon England, but not as a religious leader, and his cultural reform program’s translation of Latin works into Old English receives little attention in scholarship on Christian spirituality or medieval English vernacular theology. Such inattention is a symptom of the larger problem that Anglo-Saxon Christianity, particularly with regard to its vernacular literature, is often overlooked in the study of medieval Christian spirituality. This dissertation repositions Alfred as an Anglo-Saxon spiritual authority dedicated to teaching and learning for the purpose of Christian spiritual formation. It interprets two texts from Alfred’s reign: the Vita Ælfredi by Asser, and Alfred’s Old English translation of Gregory the Great’s Cura pastoralis. These works are treated as primary theological sources for examining Alfred’s role as a wisdom seeker and spiritual authority. The Vita Ælfredi intentionally depicts Alfred as a kingly wisdom figure with a lifelong devotion to the study of religious literature.