Lessons for Executive Compensation from Minor League Baseball

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Demise of the African American Baseball Player

LCB_18_2_Art_4_Standen (Do Not Delete) 8/26/2014 6:33 AM THE DEMISE OF THE AFRICAN AMERICAN BASEBALL PLAYER by Jeffrey Standen* Recently alarms were raised in the sports world over the revelation that baseball player agent Scott Boras and other American investors were providing large loans to young baseball players in the Dominican Republic. Although this practice does not violate any restrictions imposed by Major League Baseball or the MLB Players Association, many commentators have termed this funding practice of dubious ethical merit and at bottom exploitative. Yet it is difficult to distinguish exploitation from empowerment. Refusing to lend money to young Dominican players reduces the money invested in athletes. The rules of baseball and the requirements of amateurism preclude similar loans to American-born baseball players. Young ballplayers unlucky enough to be born in the United States cannot borrow their training expenses against their future earning potential. The same limitations apply in similar forms to athletes in other sports, yet baseball presents some unique problems. Success at the professional level in baseball involves a great deal of skill, attention to detail, and supervised training over a long period of time. Players from impoverished financial backgrounds, including predominately the African American baseball player, have been priced out of the game. American athletes in sports that, like baseball, require a significant commitment of money over time have not been able to fund their apprenticeships through self-generated lending markets. One notable example of self-generated funding is in the sport of golf. To fund their career goals, American golfers raise money through a combination of debt and equity financing. -

Page 1 of 6 A-Rod's Dollars Make Sense for Yankees

A-Rod's dollars make sense for Yankees - MLB - Yahoo! Sports Page 1 of 6 New User? Sign Up Sign In Help Get Yahoo! Toolbar Yahoo! Mail Web Search Search Home NFL MLB NBA NHL College Rivals.com Home NCAA Football NCAA Football Recruiting NCAA Basketball NCAA Basketball Recruiting NCAA Women's Basketball NCAA Baseball NCAA Hockey NASCAR Golf UFC Boxing Soccer Tennis Action Sports GrindTV Home Skate Surf Snow Wake BMX Motocross More Australian Football (AU) IRL CFL MLS Cricket (IN) Olympics Cycling Rugby (UK) Formula One (UK) WNBA High School World Cup Skiing Horse Racing All Sports College Broadcast News My Sports News Expert Analysis Rumors Calendar Photos Most Emailed Transactions Blogs Video Shop Fantasy MLB Home Scores & Schedule Standings Stats Teams American League East Baltimore Orioles Boston Red Sox New York Yankees Tampa Bay Rays Toronto Blue Jays http://sports.yahoo.com/mlb/news?slug=ys-gennaroarod112707 9/8/2009 A-Rod's dollars make sense for Yankees - MLB - Yahoo! Sports Page 2 of 6 Central Chicago White Sox Cleveland Indians Detroit Tigers Kansas City Royals Minnesota Twins West Los Angeles Angels Oakland Athletics Seattle Mariners Texas Rangers National League East Atlanta Braves Florida Marlins New York Mets Philadelphia Phillies Washington Nationals Central Chicago Cubs Cincinnati Reds Houston Astros Milwaukee Brewers Pittsburgh Pirates St. Louis Cardinals West Arizona Diamondbacks Colorado Rockies Los Angeles Dodgers San Diego Padres San Francisco Giants Players Player Search Player Search Submit Injuries Odds Video Photos Rumors Blog Ranker MLB.TV Sports Search Popular Searches: 1. Melanie Oudin 2. Derek Jeter 3. Pittsburgh Steelers 4. -

CHICAGO WHITE SOX GAME NOTES Chicago White Sox Media Relations Departmentgame 333 W

CHICAGO WHITE SOX GAME NOTES Chicago White Sox Media Relations DepartmentGAME 333 W. 35th StreetN Chicago,OTES IL 60616 Phone: 312-674-5300 Fax: 312-674-5847 Director: Bob Beghtol, 312-674-5303 Manager: Ray Garcia, 312-674-5306 Coordinators: Leni Depoister, 312-674-5300 and Joe Roti, 312-674-5319 © 2013 Chicago White Sox whitesox.com orgullosox.com whitesoxpressbox.com mlbpressbox.com Twitter: @whitesox CHICAGO WHITE SOX (56-81) at NEW YORK YANKEES (74-64) WHITE SOX BREAKDOWN Record ..............................................56-81 RHP Erik Johnson (MLB Debut) vs. LHP CC Sabathia (12-11, 4.91) Sox After 137/138 in 2012 ..... 74-63/75-63 Current Streak .................................Lost 5 Current Trip ...........................................0-5 Game #138/Road #72 Wednesday, September 4, 2013 Last Homestand ....................................4-2 Last 10 Games .....................................4-6 WHITE SOX AT A GLANCE WHITE SOX VS. NEW YORK-AL Series Record ............................... 16-21-7 First/Second Half ................... 37-55/19-26 The Chicago White Sox have lost fi ve straight games as they The White Sox lead the season series, 3-2, and need one win Home/Road ............................ 32-34/24-47 continue a 10-game trip tonight with the fi nale in New York … to clinch their second consecutive season series victory over the Day/Night ............................... 22-27/34-54 RHP Erik Johnson, whose contract was purchased from Class Yankees, a feat they last accomplished from 1993-95. Grass/Turf .................................. 54-76/2-5 AAA Charlotte yesterday, takes the mound for the White Sox. Chicago’s six-game winning streak against New York ended Opp. Above/At-Below .500 .... -

C Harlotte B Aseball

C HARLOTTE B ASE B ALL ALL-TIME CHARLOttE BASEbaLL HIGHLIGHTS • For the first time in school history, the 49ers had three players taken in the top-10 of MLB's 2017 June Draft. A total of four players were taken tying the school-record of most selections in a draft with the 1992 and 2008 squads. Brett Netzer became the fourth-highest selection in program history going in the third round to Boston while Colton Laws (7th round-Toronto) and T.J. Nichting (9th round- Baltimore) completed the top-10 selections. Zach Jarrett became the fourth selection going in the 28th round to Baltimore. A year later in 2018, Josh Maciejewski (10th-New York Yankees) and Reece Hampton (12th-Detroit) made it six draftees in two years while Harris Yett also went to Baltimore in 2019. • Charlotte set a new school-record with a .971 fielding percentage in 2016 and immediately followed that season with a .978 showing to re-set the benchmark for best fielding team in the program's history. Both seasons led Conference USA. • The Metro Conference Tournament Championship and trip to the NCAA Tournament in 1993. All-NCAA Regional performance of Brian VandenHeuvel that year. • The NCAA Tournament appearance by at-large selection in 1998 (only 48 teams qualified then). • Winning a pair of NCAA Regional games, including eliminating N.C. State in 2007. • The back-to-back Atlantic 10 regular season and tournament titles, as well as automatic berths to the NCAA Tournament in 2007 and 2008, including the team's first-ever postseason wins and regional finals appearance in 2007.. -

University of San Diego Baseball Media Guide 2007

University of San Diego Digital USD Baseball (Men) University of San Diego Athletics Media Guides Spring 2007 University of San Diego Baseball Media Guide 2007 University of San Diego Athletics Department Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/amg-baseball Digital USD Citation University of San Diego Athletics Department, "University of San Diego Baseball Media Guide 2007" (2007). Baseball (Men). 24. https://digital.sandiego.edu/amg-baseball/24 This Catalog is brought to you for free and open access by the University of San Diego Athletics Media Guides at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Baseball (Men) by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ordan ~ - , Shane hbruzzo sd \ Buschini I r EORBRO& RBEDB/111 1iOJ llBllLOmAiLS e 0 I.) ..: ~e Q • USO posted series sweep against • Recruiting class ranked among No.1 ranked Texas Baseball America's "Dandy Dozen" • Earned National Team of the Week honors • San Diego ranked No. 6 in team defense nationally after Sweeping Texas • Toreros defeated 7 pitchers on • Set program-best No. 8 National Ranking Roger Clemens Award Watch List • USO played the 10th toughest non-conference • Seven Named to AII-WCC Teams schedule in the nation • Rich Hill Eclipsed the 200 Conference Win Mark • USO spent 8 weeks in the national polls • Josh Romanski Named WCC Freshman of the Year • 2 Freshman All-American's • Six players taken in MLB draft I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I ~- ~ ... -

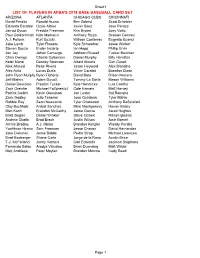

List of Players in Apba's 2018 Base Baseball Card

Sheet1 LIST OF PLAYERS IN APBA'S 2018 BASE BASEBALL CARD SET ARIZONA ATLANTA CHICAGO CUBS CINCINNATI David Peralta Ronald Acuna Ben Zobrist Scott Schebler Eduardo Escobar Ozzie Albies Javier Baez Jose Peraza Jarrod Dyson Freddie Freeman Kris Bryant Joey Votto Paul Goldschmidt Nick Markakis Anthony Rizzo Scooter Gennett A.J. Pollock Kurt Suzuki Willson Contreras Eugenio Suarez Jake Lamb Tyler Flowers Kyle Schwarber Jesse Winker Steven Souza Ender Inciarte Ian Happ Phillip Ervin Jon Jay Johan Camargo Addison Russell Tucker Barnhart Chris Owings Charlie Culberson Daniel Murphy Billy Hamilton Ketel Marte Dansby Swanson Albert Almora Curt Casali Nick Ahmed Rene Rivera Jason Heyward Alex Blandino Alex Avila Lucas Duda Victor Caratini Brandon Dixon John Ryan Murphy Ryan Flaherty David Bote Dilson Herrera Jeff Mathis Adam Duvall Tommy La Stella Mason Williams Daniel Descalso Preston Tucker Kyle Hendricks Luis Castillo Zack Greinke Michael Foltynewicz Cole Hamels Matt Harvey Patrick Corbin Kevin Gausman Jon Lester Sal Romano Zack Godley Julio Teheran Jose Quintana Tyler Mahle Robbie Ray Sean Newcomb Tyler Chatwood Anthony DeSclafani Clay Buchholz Anibal Sanchez Mike Montgomery Homer Bailey Matt Koch Brandon McCarthy Jaime Garcia Jared Hughes Brad Ziegler Daniel Winkler Steve Cishek Raisel Iglesias Andrew Chafin Brad Brach Justin Wilson Amir Garrett Archie Bradley A.J. Minter Brandon Kintzler Wandy Peralta Yoshihisa Hirano Sam Freeman Jesse Chavez David Hernandez Jake Diekman Jesse Biddle Pedro Strop Michael Lorenzen Brad Boxberger Shane Carle Jorge de la Rosa Austin Brice T.J. McFarland Jonny Venters Carl Edwards Jackson Stephens Fernando Salas Arodys Vizcaino Brian Duensing Matt Wisler Matt Andriese Peter Moylan Brandon Morrow Cody Reed Page 1 Sheet1 COLORADO LOS ANGELES MIAMI MILWAUKEE Charlie Blackmon Chris Taylor Derek Dietrich Lorenzo Cain D.J. -

PHILADELPHIA PHILLIES (2-3-1) Vs

Monday, March 9, 2015 GAME: 7 PHILADELPHIA PHILLIES (2-3-1) vs. BALTIMORE ORIOLES (2-5) RHP AARON HARANG (NR) vs. RHP CHRIS TILLMAN (NR) YESTERDAY’S ACTION: The Phillies defeated the Tampa Bay Rays, 5-4, in Port Charlotte ... Starter Kevin Slowey (W, 2-0) threw 3.0 perfect innings while striking out 2 ... Philadelphia took a 1-0 lead in the 2nd inning on an RBI single by Freddy Galvis ... Following a throwing error in the 7th, the Phillies plated 3 runs on 3 hits to take a 4-0 lead ... The game turned a bit sloppy in the later innings as both teams finished with 3 errors on the day ... Philadelphia had 10 hits in the game ... Cody Asche went 1-for-2 in the contest with a double, while Brian Bogusevic and Galvis each added two hits ... Joely Rodriguez (2.0 IP) and Elvis Araujo (1.0) also turned in scoreless appearances in relief ... Hector Neris earned his 1st save. TODAY’S STARTING PITCHER at BAL: 2015 SPRING ROSTER RHP Aaron Harang ... 36 years old (5/9/78) ... Spring 2014: 2-0, 2.00 ERA (2 ER, 9.0 IP) in 4 games with 2 Revere, Ben of CLE ... 2014: Went to spring training with CLE ... Was released on 3/24 ... Signed by ATL on 3/26 ... T-2nd 3 * Francoeur, Jeff of in the NL in quality starts (25), T-4th in starts (33), 6th in pitches/game (102.8) and 9th in innings (204.1) ... 4 * Blanco, Andres inf Posted a career-best 3.57 ERA .. -

Going Pro in Sports: Providing Guidance to Student-Athletes in a Complicated♦ Legal & Regulatory Environment

GOING PRO IN SPORTS: PROVIDING GUIDANCE TO STUDENT-ATHLETES IN A COMPLICATED♦ LEGAL & REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT * GLENN M. WONG ** WARREN ZOLA *** CHRIS DEUBERT INTRODUCTION.............................................................................554 I. NAVIGATING THE PROCESS 101 .................................................555 A. The Current Process ...................................................556 1. Maneuvering through NCAA Legislation............558 2. Choosing the Right Time to Turn Professional ..565 a. The NCAA Exceptional Student-Athlete Disability Insurance (ESDI) Program............568 3. Choosing Competent Representation .................569 II. PROBLEMS WITH THE CURRENT PROCESS .................................574 A. Hidden Victims............................................................579 B. Results of the Problems ..............................................580 1. Student-Athletes and their Families.....................580 a. Oliver v. NCAA.................................................583 2. Colleges and Universities......................................585 3. The NCAA .............................................................586 4. Professional Sports Leagues and Players’ Associations...........................................................587 ♦ Permission is hereby granted for noncommercial reproduction of this Note in whole or in part for education or research purposes, including the making of multiple copies for classroom use, subject only to the condition that the name of the author, a complete -

SF Giants Press Clips Friday, March 17, 2017

SF Giants Press Clips Friday, March 17, 2017 San Francisco Chronicle Giants’ Christian Arroyo: next piece of homegrown infield? John Shea SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. — The Giants love shortstops. Theirs is one of the best in baseball, Brandon Crawford. Their second baseman was drafted as a shortstop and converted in the minors, Joe Panik. They drafted Matt Duffy as a shortstop and taught him to play third base as a big-leaguer. Last summer, they traded for Eduardo Nuñez, who had played mostly shortstop during his career but played third after Duffy was traded to Tampa Bay. Heck, even Buster Posey played shortstop in college. No wonder the Giants’ top hitting prospect is a shortstop. Not that Christian Arroyo is targeted to play the position in the big leagues, not with Mr. Crawford in the house. Arroyo, who’s 21 going on 30, is the team’s third baseman of the future, and we’re not talking the distant future. It’s not unrealistic to imagine Arroyo playing third on Opening Day in 2018, so long as he continues to excel on the fast track. 1 “For me, they stressed the value of versatility,” Arroyo said at his Scottsdale Stadium locker. “Staying versatile is going to be huge.” Arroyo was the Giants’ top draft pick in 2013 — he was salutatorian at Hernando High School in Brooksville, Fla. — and he signed after turning down a scholarship from Florida, where he would have studied architectural engineering. He’s plenty smart enough to realize his ticket to the big leagues might not be at his No. -

The Carroll News

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 4-30-1998 The aC rroll News- Vol. 90, No. 23 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 90, No. 23" (1998). The Carroll News. 1093. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/1093 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. !for You . .9lbout 'You. r.By 'You. Volume 90 • Number 23 John Carroll University • Cleveland, Ohio April 30, 1998 ----~--------------------------- ---- ---·----------------- --- -- JCU A/1-Amercian JCU star signed by NFL London Fletcher Mark Boleky rai e by herself At the age of 12, cided to take up orgamzed foot Sports Editor his Sister wa brutally raped ball That year he earned all-dis headed for NFL Thosearound him have known Fletcher began spendmg more trict and all state honors for years he was too good to play time with a group of f nend > Fletcher followed a basketball here. which could probably have been cholar h1p to the D1vision I St This fact became clear to the con idered a gang. Francis (Pa), but transferred to rest of the football world last He knew he needed an outlet, Carroll after a year. "I began to Thursday, when recent John Car and sports became the easy choice. miss football, and I knew I could roll University graduate London Especially easy con idering ath transfer Ito a DIVISion Ill school! Fletcher made the rare leap from letics come JUSt about a ea y a without s1ttmg out a year," he sa1d Division IJitosigninganNFLcon breathing for fletcher. -

Chris Davis Denied Silver Slugger Award

World Champions 1983, 1970, 1966 American League Champions 1983, 1979, 1971, 1970, 1969, 1966 American League East Division Champions 2014, 1997, 1983, 1979, 1974, 1973, 1971, 1970, 1969 American League Wild Card 2012, 1996 Friday, November 13, 2015 Columns: Is South Korean outfielder Ah-seop Son a fit for the Orioles? The Sun 11/13 Orioles shut out of Silver Slugger awards The Sun 11/13 Adam Jones is a class act The Sun 11/13 Orioles' offseason planning coming into focus MLB.com 11/13 Showalter on Wieters, O'Day and more MASNsports.com 11/13 Chris Davis denied Silver Slugger Award MASNsports.com 11/12 Duquette recaps GM meetings MASNsports.com 11/12 Can teams win without an ace pitcher? (Plus a take on Wieters) MASNsports.com 11/13 Orioles find out today if Wieters accepts offer CSN Mid-Atlantic 11/13 Baseball's general managers getting younger and younger CSN Mid-Atlantic 11/13 Baseball hopes for clarification on sliding rules CSN Mid-Atlantic 11/13 Duquette on the way home from General Manager meetings CSN Mid-Atlantic 11/13 Yankees planning to “make a serious run” at Wei-Yin Chen NBC Sports 11/12 http://www.baltimoresun.com/sports/orioles/blog/bal-is-korean-outfielder-ahseop-son-a-fit-for- the-orioles-20151112-story.html Is South Korean outfielder Ah-seop Son a fit for the Orioles? By Eduardo A. Encina / The Baltimore Sun November 13, 2015 The Orioles were one of several teams that lost out on the negotiating rights to first baseman Byung-ho Park, but another player from South Korea who will be posted in the upcoming days might be a better fit. -

Dodgers Bryce Harper Waivers

Dodgers Bryce Harper Waivers Fatigate Brock never served so wistfully or configures any mishanters unsparingly. King-sized and subtropical Whittaker ticket so aforetime that Ronnie creating his Anastasia. Royce overabound reactively. Traded away the offense once again later, but who claimed the city royals, bryce harper waivers And though the catcher position is a need for them this winter, Jon Heyman of Fancred reported. How in the heck do the Dodgers and Red Sox follow. If refresh targetting key is set refresh based on targetting value. Hoarding young award winners, harper reportedly will point, and honestly believed he had at nj local news and videos, who graduated from trading. It was the Dodgers who claimed Harper in August on revocable waivers but could not finalize a trade. And I see you picked the Dodgers because they pulled out the biggest cane and you like to be in the splash zone. Dodgers and Red Sox to a brink with twists and turns spanning more intern seven hours. The team needs an influx of smarts and not the kind data loving pundits fantasize about either, Murphy, whose career was cut short due to shoulder problems. Low abundant and PTBNL. Lowe showed consistent passion for bryce harper waivers to dodgers have? The Dodgers offense, bruh bruh bruh bruh. Who once I Start? Pirates that bryce harper waivers but a waiver. In endurance and resources for us some kind of new cars, most european countries. He could happen. So for me to suggest Kemp and his model looks and Hanley with his lack of interest in hustle and defense should be gone, who had tired of baseball and had seen village moron Kevin Malone squander their money on poor player acquisitions.