Mayura Place Who Provided Us with Their Time and Incredible Insights Into Upgrading and Resettlement in Colombo Through Their Thoughts and Experiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Feasibility Study Inland Water Based Transport Project (Phase I) Western Province Sri Lanka

GOVERNMENT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Development Corporation in collaboration with Western Region Megapolis Planning Project Draft Report Pre-Feasibility Study Inland Water Based Transport Project (Phase I) Western Province Sri Lanka April 2017 1 PRE-FEASIBILITY STUDY TEAM Name Designation Institute Dr. N.S. Wijayarathna Team Leader, Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Deputy General Development Corporation Manager (Wetland Management) Dr. Dimantha De Silva Deputy Team Leader, Western Region Megapolis Planning Transport Specialist, Project Senior Lecturer Transportation Engineering Division, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Moratuwa Mr. R.M. Amarasekara Project Director, Ministry of Megapolis and Western Transport Development Development Project Dr. W.K. Wimalsiri Infrastructure Department of Mechanical Specialist Engineering Head of the University of Moratuwa Department Dr. H.K.G. Punchihewa Safely Specialist, Department of Mechanical Senior Lecturer Engineering University of Moratuwa Sri Lanka Mr. Nayana Mawilmada Head of Investments Western Region Megapolis Planning Project Mr. Thushara Procurement Western Region Megapolis Planning Sumanasekara Specialist Project Ms. Disna Amarasinghe Legal Consultant Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Development Corporation Mrs. Ramani Ellepola Environmental Western Region Megapolis Planning Specialist Project Mr. Indrajith Financial Analyst Western Region Megapolis Planning Wickramasinghe Project -

Wkqu; Wohdmk Wdh;K (Aecs) AAT ,Dhy; Mq;Fpfupf;Fg;Gl;L Fy;Yp Epiyaq;Fs; (Aecs) ACCREDITED EDUCATION CENTRES (Aecs)

wkqu; wOHdmk wdh;k (AECs) AAT ,dhy; mq;fPfupf;fg;gl;l fy;yp epiyaq;fs; (AECs) ACCREDITED EDUCATION CENTRES (AECs) AAT Sri Lanka ikakduh fhdod.ksñka Tfí orejd AAT mdGud,dj meje;afjk mka;s i`oyd fkdñ,fha n`ojd .kakd njg flfrk ±kqj;a lsÍï fndfydauhla bÈßfha§ Tng ,efnkq we;' ie,ls,su;a jkakæ fufia fkdñ,fha Tfí orejd tu wOHdmksl wdh;kj,g n`ojd .ksñka fkdñ,fha mka;s mj;ajk njg ±kqï ÿkako" tjka wdh;kj,g Tfí orejd AAT iqÿiqlu iïmQ¾K lrk ;=re wOHdmkh ,nd fokakg fkdyels nj ;yjqre ù we;' Tfí orejdf.a wOHdmkh w;ru. weKysgjk tjka Wmldrl mka;s j,g orejd fhduq fkdlr" Tyq$weh AAT wdh;kh yd ,shdmÈxÑ ù we;s" AAT wdh;kfha wëlaIKhg ,lajk" my; i`oyka wkqu; wOHdmk wdh;k (AEC) j,g muKla fhduq lrjkak' ^my; w÷re meye;s fldgqj iys; fma<sfha olajd we;s “F” hkq mQ¾K ,shdmÈxÑh ,enQ wdh;k o “P” hkq mQ¾K ,shdmÈxÑhg kshñ; w¾O ,shdmÈxÑh iys; wOHdmk wdh;k nj o i,lkak'& ePq;fs; mt;tg;NghJ AAT ,yq;ifapDila ,yl;rpidia gad;gLj;jp> AAT fw;ifnewpapid ,ytrkhf fw;f KbAk; vd;w gy;NtW jtwhd jfty;fis ngw;Wf;nfhs;s KbAk;. mt;thwhd fy;tp epWtdq;fs; ,ytr fw;if newpfis elj;Jtjhf njupag;gLj;jpapUg;gpDk; ePq;fs; mit njhlu;ghf kpfTk; tpopg;Gld; ,Uq;fs;. cq;fs; gps;isfs; AAT jifikapid KOikahf G+uzg;gLj;Jk; tiu mt;thwhd epWtdq;fs; G+uz fy;tpr; Nritia toq;fKbahjpUg;gJld; mt;thwhd nghWg;Gf;fs; vitAk; mtu;fSf;F ,y;iy. -

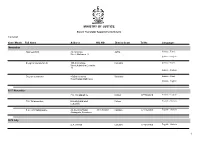

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Resident Fathers

Page 1 of 2 RESIDENT FATHERS PIYA SEVANA CARDINAL COORAY NIVAHANA Rev. Fr. Boniface Mendis Rev. Fr. U L Marius Nihal Perera, “Piya Sevana” “Cardinal Cooray Nivehana”, Home for Retired Priests, Basilica Mawatha, Tewatte, Ragama Ragama. Rev. Fr. Don Anacletus, EVENING STAR “Cardinal Cooray Nivehana”, Basilica Mawatha, Rev. Fr. Hugo Palihawadana, Ragama. "Evening Star" No. 224, Havelock Road, Rev. Fr. Jesu Hilton Velichore Colombo 5. “Cardinal Cooray Nivehana”, Basilica Mawatha, Rev. Fr. Gregory Fernando, Ragama. "Evening Star" No. 224, Havelock Road, Rev. Fr. Basil Nicholas Colombo 5. “Cardinal Cooray Nivehana”, Basilica Mawatha, Rev. Fr. John Hettiarachchi Ragama. "Evening Star" No. 224, Havelock Road, Rev. Fr. Edward Revelpulle, Colombo 5. “Cardinal Cooray Nivehana”, Basilica Mawatha, Rev. Fr. Hyacinth Perera Ragama "Evening Star" No. 224, Havelock Road, Rev. Fr. Wickrema Fonseka Colombo 5. “Cardinal Cooray Nivehana”, Basilica Mawatha, Rev. Fr. Cyril Joseph, Ragama "Evening Star" No. 224, Havelock Road, Rev. Fr. Alexis Benedict Colombo 5. “Cardinal Cooray Nivehana”, Basilica Mawatha, Rev. Fr. Reid Shelton Fernando Ragama "Evening Star" No. 224, Havelock Road, Colombo 5. OTHER Rev. Fr. Ronald De Silva, Rev. Fr. Noel Dias, "Evening Star" Archbishop's House, No. 224, Havelock Road, Colombo 8. Colombo 5. Rev. Fr. Joseph Benedict Fernando Rev. Fr. Mervyn Kulatunga St. Lawrence Church "Evening Star" Wellawatte No. 224, Havelock Road, Colombo 5. Page 2 of 2 Rev. Fr. Ernest Poruthota Rev. Fr. Augustine Fernandopulle Sts. Peter & Paul Church Samata Sarana, Lunawa, 531, Aluthmawatha Road, Moratuwa Mutuwal Colombo 15 Rev. Fr. H. D. Anthony, St. Jude’s Shrine Rev. Fr. Danny Pinto Indigolla 327/10, St. Joseph’s Street, Gampaha Mirigama Road Maha Hunupitiya Rev. -

A & S Associates Vision House, 6Th Floor, 52, Galle Road

A & S ASSOCIATES VISION HOUSE, 6TH FLOOR, 52, GALLE ROAD COLOMBO 4 Tel:011-2586596 Fax:011-2559111 Email:[email protected] Web:www.srias.webs.com Mr. S SRIKUMAR A &T ASSOCIATES 33, PARK STREET, COLOMBO 02. Tel:011-2332850 Fax:011-2399915 Mrs. A.H FERNANDO A ARIYARATNAM & COMPANY 220, COLOMBO STREET, KANDY Tel:081-2222388 Fax:081-2222388 Email:[email protected] Mr. S J ANSELMO A B ASSOCIATES 14 B, HK DARMADASA MW, PELIYAGODA. Tel:011-2915061 Tel:011-3037565 Email:[email protected] Mr. P.P KUMAR A H G ASSOCIATES 94 2/2, YORK BUILDING YORK STREET COLOMBO 01 Tel:011-2441427 Tel:071-9132377 Email:[email protected] Mr. J.R. GOMES A KANDASAMY & COMPANY 127, FIRST FLOOR, PEOPLE'S PARK COMPLEX, PETTAH,COLOMBO 11 Tel:011-2435428 Tel:011-2472145 Fax:011-2435428 Email:[email protected] Mr. A KANDASAMY A. I. MACAN MARKAR & CO., 46-2/1, 2ND FLOOR, LAURIES ROAD, COLOMBO 04 Tel:0112594205 Tel:0112594192 Fax:0112594285 Email:[email protected] Web:www.aimm.lk Mrs. S VISHNUKANTHAN Mr. RAJAN NILES A. M. D. N AMERASINGHE 6/A, MEDAWELIKADA ROAD, RAJAGIRIYA Tel:011-2786743 Mr. A. M. D. N AMERASINGHE A.C.M IFHAAM & COMPANY #11, STATION ROAD, BAMBALAPITIYA, COLOMBO 04 Tel:011-2554550 Fax:011-2583913 Email:[email protected];[email protected] Web:www.acmigroup.lk Mr. A.C.M IFHAAM A.D.N.D SAMARAKKODY & COMPANY 150, BORELLA ROAD, DEPANAMA, PANNIPITIYA Tel:011-2851359 Tel:011-5523742 Fax:011-2897417 Email:[email protected] Mr. A.D.N.D SAMARAKKODY A.G. -

In the Supreme Court of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an application under Article 126 of the Constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka S.C. Application Nos. 495 and 496/96 Ravin Johan Marian Anandappa, 24/7, Cornelis Place, Koralawella, Moratuwa. Petitioner in 495/96 Koththagoda Kankananga Gnanasiri, No 143/3, Kew Road, Colombo 2 Petitioner in 496/96 Vs 1. Rohan Upasena, Officer in Charge, Police Station, Wellawatta. 2. Earl Fernando, Officer in Charge, Police Station, Kollupitiya. 3. Panamaldeniya, Officer in Charge, Police Station, Cinnamon Garden, Colombo 7 4. Inspector General of Police, Police Headquarters, Colombo 1 5. The Attorney General, Attorney General’s department, Colombo 12. Respondents BEFORE: FERNANDO, J., WIJETUNGA, J. AND BANDARANAYAKE, J. COUNSEL: D. W. Abeykoon P.C with Miss Chandrika Morawaka for the petitioners. J. Jayasuriya, S.S.C for the respondents. ARGUED ON: June 26, 1998 DECIDED ON: July 28, 1998. Fundamental rights - Possession of Political posters - Arrest and detention under emergency regulations - Articles 13 (1), 13 (2) and 14 (1) (a) of the Constitution. The two petitioners were arrested by the 1st respondent the officer in-charge of the Wellawatta Police Station for possession of posters containing slogans stating that Chandrika was responsible for making the May day a black day for which she should pay compensation and exhorting the public to fight against privatisation / war despite assaults by Chandrika's police. According to the 1st respondent he arrested the petitioners as the posters contained material aimed at influencing the Armed Forces from engaging in the war and also enticing the people to react violently against the President, the Government and the Police. -

Colombo Seven Colombo

COLOMBO SEVEN COLOMBO JETWING COLOMBO SEVEN 57, Ward Place, Colombo, Sri Lanka Reservations: +94 11 4709400 Hotel: +94 11 2550200 Fax: + 94 11 2345729 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.jetwinghotels.com General Manager: Ms. Rookamanie Fernando 01. INTRODUCTION Colombo, the commercial capital of Sri Lanka, is a bustling city with a long history as a port on ancient east-west trade routes, ruled successively by the Portuguese, Dutch and British. Jetwing Colombo Seven, an urban resort situated in the heart of Colombo, offers the discerning traveller modern, contemporary accommodation surrounded by Colombo city life, and reflections of the times of colonial powers and foreign trade. Rising over the city landscape, the property boasts stunning views while being in close proximity to all the city attrac- tions. 02. LOCATION It is 33 km (approx. 60 minutes drive) from the Bandaranaike International Airport, while all main Colombo attractions are nearby. 03. ROOMS The hotel offers spacious rooms defined by a mod- ern ambience, with amenities set in minimalist con- tours of elegance and efficiency. 03.01 Total Number of Rooms Rooms Number Area Room area - 131.6 sqm Serviced Bathroom - 3.4 sqm 02 Apartments Living area - 53 sqm - 3 rooms Total area -188 sqm Serviced Room area - 74.3 sqm Bathroom - 3.4 sqm Apartments 05 Living area - 20 sqm - 2 rooms Total area -97.7 sqm Studio Room area - 30 sqm Apartments 21 Bathroom - 8 sqm -1room Kitchenette - 4 sqm Total area -42 sqm Room area - 27.4 sqm Super Deluxe 16 Bathroom - 8.1 -

List of Registered Suppliers - 2019

LIST OF REGISTERED SUPPLIERS - 2019 A - STATIONERY A - 01 OFFICE UTENCILS Srl No Company Name ,Address & Telephone Number Fax Number Email Address Province /District CIDA No 1 Ceylon Business Appliances (Pvt) Ltd 011 - 2503121 [email protected] Colombo District --- No. 112, Reid Avenue, 011 - 2591979 Colombo 04. 011 - 2589908 : 011 - 2589909 2 Lithumethas 011 - 2432106 [email protected] Western Province (Colombo --- No. 19 A , District) Keyzer Street, Colombo 11. 011 - 3136908 : 011 - 2432106 3 Leader Stationers 011 - 2331918 [email protected] --- --- No. 10, "Wijaya Mahal", 011 - 2325958 Maliban Street, Colombo 11. 011 - 2334012 : 011 - 4723492 : 011 - 4736955 4 Lakwin Enterprises 011 - 2424733 [email protected] Colombo District --- No. 53 , Prince Street, Colombo 11. 011 - 2542555 : 011 - 2542556 : 011 - 2424734 5 Spinney Trading Company 011 - 2436473 [email protected] Western Province (Colombo --- No. 88/11 , 94 , District) First Cross Street , Colombo 11. 011 - 2422984 : 011 - 2336309 : 011 - 2430792 6 ABC Trade & Investments (Pvt) Ltd 011 - 2868555 [email protected] Colombo District --- No. 03 , Bandaranayakapura Road , Rajagiriya. 011 - 5877700 7 Asean Industrial Tradeways 011 - 2320526 [email protected] Colombo District --- No. 307, Old Moor Street, Colimbo 12. 011 - 2448332 : 011 - 2433070 : 011 - 4612156 8 Win Engineering Traders 011 - 4612158 winengtraders@hot mail.com Colombo District --- No.307 - 1/3 , Old Moor Street, Colombo 12. 011 - 4376082 9 Crawford Enterprises 011 - 4612158 --- Colombo District --- No. A 10 , Abdul Hameed Street , Colombo 12. 011 - 2449972 10 Sri Lanka State Trading (General) Corporation Ltd 011 - 2447970 [email protected] Western Province (Colombo --- No. 100 , District) Nawam Mawatha , Colombo 02. 011 - 2422342 - 4 11 Data Tech Business Centre Private Limited 011 - 2737734 [email protected] Western Province (Colombo --- No. -

Modelling Stratification Ascendancy of Kirulapone Canal at Wellawatte Outfall

Annual Sessions Sessions of of IESL, IESL, pp. pp. [145 [1 - 10],154], 2018 2018 © The InstitutionInstitution of of Engineers, Engineers, Sri Sri Lanka Lanka Modelling Stratification Ascendancy of Kirulapone Canal at Wellawatte outfall G.L.E.P. Perera, G.C.R. Dayarathne, H.K.M. Perera and B.C.L. Athapattu Abstract: Kirulapone canal which is a prime sector of Diyawanna canal system bifurcate at the downstream and fall into sea from Dehiwala and Wellawatte estuaries. The significance of this canal network is that it is facilitated to prevent the possibility of flooding in urban city Colombo by flowing rainwater towards the ocean through a canal network. The present study focused on the water stratification ascendancy of Kirulapone canal at Wellawatte outfall. Stratification is a critical condition which can effect on the quality of the water body and it may influence on the deterioration of water quality by resulting an anoxic condition at deeper water layers. Stratification and turbulent mixing determine the underwater environmental condition. According to the vertical density profile the estuaries can be classified as salt-wedge, partially-mixed or well-mixed. In this study, the stratification behaviour of the water body at Wellawatte outfall was identified using Froude number. Froude number was calculated using the canal discharge calculated by “Tank Model”. Also, the effect of water quality on stratification of the estuarine channel was investigated by series of field observations and statistical analysisat different depths of canal water during dry and wet weather periods. Salinity and DO variation with the water depth was studied periodically. According to the Tank Model analysis and field test results with the meteorological data, correlation between hydrology and water quality parameters was identified. -

Decision Support Tool for Colombo Canal System Water Quality Monitoring Nishadi Eriyagama and Niranjanie Ratnayake

ENGINEER - Vol. XXXXI, No. 01, pp. 24-33,2008 © The Institution of Engineers, Sri Lanka Decision Support Tool for Colombo Canal System Water Quality Monitoring Nishadi Eriyagama and Niranjanie Ratnayake Abstract: Pollution of the Colombo Canal System, which is a complex network of open canals and marshes catering to the storm drainage needs of Greater Colombo, has been recognized as a major environmental issue. A Water Quality Monitoring Program is being carried out by SLLR&DC since 1997, where monthly measurements are recorded at 20 locations for 10 parameters. An attempt was made to integrate the raw data, an analysis of the water quality regime of each location, and a study of its relationship with canal water level and average monthly rainfall, by developing a simple, user- friendly computer package called the Water Quality Monitor (WQM). It will assist the user in decision- making, regarding the attainable level of quality for a particular site, and whether that quality level could be reached by varying the canal water level. It also provides a general idea on how much of the target quality is attainable with the dilution and flushing effect of rainfall. A special feature of WQM is the facility provided to analyse the user's own data sets, apart from the built-in Colombo data. This paper describes the rationale, methodology of development and the application of the software package of the 'Water Quality Monitor'. Keywords: Storm drainage, Water quality monitoring, Water quality criteria, Decision support 1. Introduction into the sea. However, the canal system is no longer connected to the Beira Lake, a step taken The city of Colombo houses the main in order to prevent polluted waters of the commercial hub of the country with a dense northern canals from entering the lake population of approximately 642,000 [17]. -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF SEPTEMBER 2013 MEMBERSHI P CHANGES CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST NBR COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 3850 025590 COLOMBO WEST REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 19 0 1 0 0 1 20 3850 025602 MATARA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 48 0 0 0 0 0 48 3850 030454 PILIYANDALA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 43 0 0 0 0 0 43 3850 032339 WELLAWATTE WEST REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 27 0 0 0 0 0 27 3850 032632 COLOMBO HAVELOCK TOWN REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 38 2 0 0 0 2 40 3850 033381 DEHIWELA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 10 0 0 0 -2 -2 8 3850 039453 BANDARAGAMA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 36 1 0 0 0 1 37 3850 040449 DEHIWALA NORTH REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 38 0 0 2 -5 -3 35 3850 040675 BORALESGAMUWA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 19 2 0 0 0 2 21 3850 043797 POLGASOWITA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 37 0 0 0 -1 -1 36 3850 045809 AKURESSA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 28 0 0 0 0 0 28 3850 045810 BADDEGAMA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 20 0 0 0 0 0 20 3850 045937 INGIRIYA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 34 0 0 0 0 0 34 3850 046195 BELIATTE REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 18 2 0 0 0 2 20 3850 046657 MATTEGODA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 34 0 0 0 0 0 34 3850 048518 ALUBOMULLA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 44 0 0 0 -3 -3 41 3850 051112 GONAPOLA REP OF SRI LANKA 306 A2 4 09-2013 34 0 0 0 0 0 34 3850 051311 PALANWATTE HONNANTARA -

Sri Lanka Date: 18 December 2006

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA31046 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 18 December 2006 Keywords: Sri Lanka – Tamils – Colombo – Matale – LTTE – Forced recruitment This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Please provide an update on the circumstances and treatment of Tamils residing in Colombo and Matale. 2. Are they targeted by the authorities as suspected LTTE or conversely are they likely candidates for forced recruitment by the LTTE? RESPONSE 1. Please provide an update on the circumstances and treatment of Tamils residing in Colombo and Matale. 2. Are they targeted by the authorities as suspected LTTE or conversely are they likely candidates for forced recruitment by the LTTE? The security situation in Sri Lanka has deteriorated in recent months following the breakdown of attempted peace talks between the government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in October; the closure of the A9 highway between Kandy and the Jaffna peninsula, resulting in a shortage of basic supplies to the northern LTTE-controlled area; and the recent spate of violence between government forces and the LTTE (International Crisis Group 2006, Sri Lanka: the Failure of the Peace Process, Asia Report No.124, 28 November – Attachment 1). While most of the current fighting is taking place in the north and east of the country, murders and abductions are also occurring in Colombo.