David V. Goliath (1 Samuel 17): What Is the Author Doing with What He Is Saying?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moses -- Exodus 2:1-10 David and Goliath (I Samuel 17:1-58)

Moses -- Exodus 2:1-10 Exodus 2:1-10 New International Version (NIV) The Birth of Moses 2 Now a man of the tribe of Levi married a Levite woman, 2 and she became pregnant and gave birth to a son. When she saw that he was a fine child, she hid him for three months. 3 But when she could hide him no longer, she got a papyrus basket[a] for him and coated it with tar and pitch. Then she placed the child in it and put it among the reeds along the bank of the Nile. 4 His sister stood at a distance to see what would happen to him. 5 Then Pharaoh’s daughter went down to the Nile to bathe, and her attendants were walking along the riverbank. She saw the basket among the reeds and sent her female slave to get it. 6 She opened it and saw the baby. He was crying, and she felt sorry for him. “This is one of the Hebrew babies,” she said. 7 Then his sister asked Pharaoh’s daughter, “Shall I go and get one of the Hebrew women to nurse the baby for you?” 8 “Yes, go,” she answered. So the girl went and got the baby’s mother. 9 Pharaoh’s daughter said to her, “Take this baby and nurse him for me, and I will pay you.” So the woman took the baby and nursed him. 10 When the child grew older, she took him to Pharaoh’s daughter and he became her son. -

Observations on 666 in the Old Testament

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Engineering and Information Faculty of Informatics - Papers (Archive) Sciences 6-1999 Observations on 666 in the Old Testament M. G. Michael University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers Part of the Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Michael, M. G.: Observations on 666 in the Old Testament 1999. https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers/672 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Observations on 666 in the Old Testament Disciplines Physical Sciences and Mathematics Publication Details This article was originally published as Michael, MG, Observations on 666 in the Old Testament, Bulletin of Biblical Studies, 18, January-June 1999, 33-39. This journal article is available at Research Online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers/672 RULLeTIN OF RIRLICkL STuDies Vol. 18, January - June 1999, Year 28 CONTENTS Prof. George Rigopoulos, ...~ Obituary for Oscar Cullmann 5 .., Prof. Savas Agourides, The Papables of Preparedness in Matthew's Gospel 18 Michael G. Michael, Observations on 666 in the Old Testament. 33 Prof. George Rigopoulos, Jesus and the Greeks (Exegetical Approach of In. 12,20-26) (Part B'). .. 40 Zoltan Hamar, Grace more immovable than the mountains 53 Raymond Goharghi, The land of Geshen in Egypt. The Ixos 99 Bookreviews: Prof. S. Agourides: Jose Saramagu, The Gospel according to Jesus - Karen Armstrong, In the Beginning, A new Interpretation ojthe Book ojGenesis ; 132 EDITIONS «ARTOS ZOES» ATHENS RULLeTIN OF RIRLIC~L STuDies Vol. -

Narrator, God, Samuel, David, Jesse, Goliath, Saul, Israelite Soldier, Eliab

1 God Chooses David 1 Samuel 16-17 Characters: Narrator, God, Samuel, David, Jesse, Goliath, Saul, Israelite Soldier, Eliab Narrator: God had warned his people that a human king could easily be corrupted. After Samuel had anointed Saul as king, Saul began turning away from God. Because of Saul’s sins, God let the Philistines to begin to invade and take over the lands of the Israelites. Before the end of Saul’s life, God decided that it was time for the next king to be chosen. God: Samuel! How long will you be upset about Saul, since I have rejected him as king over Israel? Do not worry, for I have chosen a new king—one of the sons of Jesse of Bethlehem. Fill your horn with oil so you can go to Bethlehem and anoint this new king. Samuel: Lord, how can I go to Bethlehem? Saul will surely find out that I am going to anoint the new king, and kill me for it. God: Take a cow with you, and tell Saul that you are going to sacrifice the cow at Bethlehem to the Lord. Invite Jesse to the sacrifice, and anoint the person I indicate. Narrator: Samuel went to Bethlehem, and did was God had said. He had invited Jesse and his family to the sacrifice, and began looking among Jesse’s sons for the one he was to anoint the new king. Samuel saw each of Jesse’s eldest seven sons, and noticed they were big, strong, and handsome. Samuel prayed about each of the sons, asking if he was to anoint him to be king. -

Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs by Daniel D

Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs by Daniel D. Stuhlman BHL, BA, MS LS, MHL In support of the Doctor of Hebrew Literature degree Jewish University of America Skokie, IL 2004 Page 1 Abstract Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs By Daniel D. Stuhlman, BA, BHL, MS LS, MHL Because of the differences in alphabets, entering Hebrew names and words in English works has always been a challenge. The Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) is the source for many names both in American, Jewish and European society. This work examines given names, starting with theophoric names in the Bible, then continues with other names from the Bible and contemporary sources. The list of theophoric names is comprehensive. The other names are chosen from library catalogs and the personal records of the author. Hebrew names present challenges because of the variety of pronunciations. The same name is transliterated differently for a writer in Yiddish and Hebrew, but Yiddish names are not covered in this document. Family names are included only as they relate to the study of given names. One chapter deals with why Jacob and Joseph start with “J.” Transliteration tables from many sources are included for comparison purposes. Because parents may give any name they desire, there can be no absolute rules for using Hebrew names in English (or Latin character) library catalogs. When the cataloger can not find the Latin letter version of a name that the author prefers, the cataloger uses the rules for systematic Romanization. Through the use of rules and the understanding of the history of orthography, a library research can find the materials needed. -

Curriculum About the 2017 Unshakeable Tour

Pre-Conference Curriculum About the 2017 Unshakeable Tour Teenagers are often overlooked and underestimated, but God wants to use them to bring about incredible transformation for God’s Kingdom. Using the story of young David facing an immense giant, the Unshakeable Tour will inspire teenagers to find an unshakeable faith in Jesus Christ and equip them to answer Christ’s call to make disciples who make disciples. Register your group for the 2017 Unshakeable Tour today! REGISTER © Copyright 2016 Dare 2 Share Ministries. All rights reserved. Reprint permission is given for the attached handouts for use in the lesson. All scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, is taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright © 1996, 2004, 2007, 2015 by Tyndale House Foundation. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188. All rights reserved. 2017 STUDENT EVANGELISM TRAINING CONFERENCE PRE-CONFERENCE CURRICULUM Lesson 1—Unlikely Big Idea: David’s youth and inexperience made him an unlikely candidate for taking down Goliath; but God loves to use the underestimated and overlooked to accomplish the impossible. And God has plans for YOU, too! Key Scripture: 1 Samuel 17:32 - 37 Advanced Prep and Supplies: • Video projection equipment and Unshakeable promotional DVD or online video available at http://www.dare2share.org/unshakeable/. • 2017 Unshakeable Tour information (including your group’s travel details) to pass on to your students and their parents. WARM UP Open with prayer. Invite your students to call out their favorite underdog characters from stories, movies or TV shows. Pair these underdogs off in a few head-to-head competitions and ask your students to vote for whichever is their favorite by moving to opposite sides of the room. -

Mario Minniti Young Gallants

Young Gallants 1) Boy Peeling Fruit 1592 2) The Cardsharps 1594 3) Fortune-Teller 1594 4) David with the Head 5) David with the Head of Goliath 1607 of Goliath 1610 Mario Minniti 1) Fortune-Teller 1597–98 2) Calling of Saint 3) Musicians 1595 4) Lute Player 1596 Matthew 1599-00 5) Lute Player 1600 6) Boy with a Basket of 7) Boy Bitten by a Lizard 8) Boy Bitten by a Lizard Fruit 1593 1593 1600 9) Bacchus 1597-8 10) Supper at Emmaus 1601 Men-1 Cecco Boneri 1) Conversion of Saint 2) Victorious Cupid 1601-2 3) Saint Matthew and the 4) John the Baptist 1602 5) David and Goliath 1605 Paul 1600–1 Angel, 1602 6) Seven Acts of Mercy, 1606 7) Seven Acts of Mercy, 1606 7) Nativity with Saints Lawrence and Francis, 1609 K 1) Martyrdom of Saint 2) Conversion of Saint Paul 3) Saint John the Baptist at Self portraits Matthew 1599-1600 1600-1 the Source 1608 1) Musicians 1595 2) Bacchus1593 3) Medusa 1597 4) Martyrdom of Saint Matthew 1599-1600 5) Judith Beheading 6) David and Goliath 7) David with the Head 8) David with the Head 9) Ottavia Leoni, 1621-5 Holofernes 1598 1605 of Goliath 1607 of Goliath 1610 Men 2 Women Fillide Melandroni 1) Portrait of Fillide 1598 2) Judith Beheading 3) Conversion of Mary Holoferne 1598 Magdalen 1599 4) Saint Catherine 5) Death of the 6) Magdalen in of Alexandria 1599 Virgin 1605 Ecstasy 1610 A 1) Fortune teller 1594 2) Fortune teller 1597-8 B 1) Madonna of 2) Madonna dei Loreto 1603–4 Palafrenieri 1606 Women 1 C 1) Seven Acts of Mercy 2) Holy Family 1605 3) Adoration of the 4) Nativity with Saints Lawrence 1606 Shepherds -

David and Goliath by Sharla Guenther

DLTK's Bible Stories for Children David and Goliath by Sharla Guenther Saul had been king, but he kept disobeying God so God asked Samuel to find a new king. God said to Samuel, "Go to Bethlehem and there is a man named Jesse with eight sons. One of them will be the next king." When Samuel first met the sons he automatically thought that the oldest son named Eliab would be the king that God had chosen. But the Lord said to Samuel, "Do not look at the way he looks or how big he is. Eliab is not the one I have chosen, the way he looks doesn't matter to me, I look at the heart." Jesse brought more of his sons to meet Samuel but none of them God had chosen either. Samuel asked Jesse, "Have I met all your sons?" Jesse replied, "I have one son left named David, he's the youngest, and he's out looking after the sheep. I will bring him here to meet you." As soon as Samuel saw him the Lord spoke to him and said, "He is the one." So Samuel anointed him with oil which was a special way of promising him that he would be the next king. And from that day on the power of the Lord was with David. David continued to take care of his father's sheep in the fields. When he didn't have much to do in the field he played instruments, and wrote songs and poems that you can find in the book of Psalms in your Bible. -

Goliath's Height by William D. Barrick, Th.D. the Master's Seminary It Is

Goliath’s Height by William D. Barrick, Th.D. The Master’s Seminary It is true that a Dead Sea Scroll document (4QSam-b) has 4 cubits and a span (approx. equivalent to 6.5 feet) for Goliath’s height, while 1 Samuel 17:4 reads 6 cubits and a span (approx. equivalent to 9.5 feet). Since some scholars approach the Scriptures with the hermeneutics of doubt, some have questioned its accuracy regarding the height of Goliath for a long time. With 4QSam-b they feel their doubt has been vindicated and leap at the opportunity to point out the apparent discrepancy. The reduction of Goliath’s height in 4QSam-b, when carefully examined, appears to be a deliberate alteration, not the reflection of an original reading nor even a scribal slip of the pen. When one takes into account the description of Goliath’s weapons, the biblical text’s reading makes more sense. In 1 Samuel 17:5 the weight of his bronze armor made of chainlink mail was 5000 shekels (approx. equivalent to 126 pounds). In verse 7 the shaft of his spear was like a weaver’s beam and the blade alone was made of 600 shekels of iron (approx. equivalent to 15 pounds). Consider also the fact that King Saul, who stood head and shoulders above other men (1 Sam 9:2; 10:23), was probably close to 6.5 feet in height himself. Therefore, it is really peculiar that Saul’s men would be retreating from before Goliath in such fear (1 Sam 17:24), if he was just a man like Saul. -

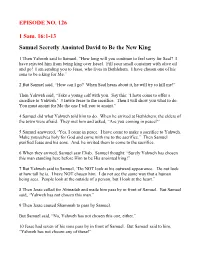

Samuel Secretly Anointed David to Be the New King

EPISODE NO. 126 1 Sam. 16:1-13 Samuel Secretly Anointed David to Be the New King 1 Then Yahweh said to Samuel, “How long will you continue to feel sorry for Saul? I have rejected him from being king over Israel. Fill your small container with olive oil and go! I am sending you to Jesse, who lives in Bethlehem. I have chosen one of his sons to be a king for Me.” 2 But Samuel said, “How can I go? When Saul hears about it, he will try to kill me!” Then Yahweh said, “Take a young calf with you. Say this: ‘I have come to offer a sacrifice to Yahweh.’ 3 Invite Jesse to the sacrifice. Then I will show you what to do. You must anoint for Me the one I tell you to anoint.” 4 Samuel did what Yahweh told him to do. When he arrived at Bethlehem, the elders of the town were afraid. They met him and asked, “Are you coming in peace?” 5 Samuel answered, “Yes, I come in peace. I have come to make a sacrifice to Yahweh. Make yourselves holy for God and come with me to the sacrifice.” Then Samuel purified Jesse and his sons. And, he invited them to come to the sacrifice. 6 When they arrived, Samuel saw Eliab. Samuel thought: “Surely Yahweh has chosen this man standing here before Him to be His anointed king!” 7 But Yahweh said to Samuel, “Do NOT look at his outward appearance. Do not look at how tall he is. -

STORY 1: Choosing a King

Make sure your name and address are written here. Age: Name: Address: Level 0 Bible Stories Class Leader: bibletimewww.besweb.com STORY 1: Choosing a king This story is about God looking at the heart. READ: 1 Samuel Adult Guidance - Talk about what we look like and how we recognise each other by our faces. 16: 1 – 13 We see the outside, but the Bible teaches that God looks at the inside – our hearts. C6 God sent Samuel to Jesse’s family to find a new king. Samuel wanted to choose Eliab because he looked like a king. But God said no. Jesse sent for his son David who was looking after the sheep. God told Samuel to choose Eliab David David. Who did God choose? Put a (✓) in the box. God could see into David’s heart and knew he was the right person to be king. / 10 level 0 bibletime Level 0 Bible Stories C6 STORY 2: Fighting Goliath This story is about God helping David to be brave. READ: 1 Samuel Adult Guidance - Find something to compare with Goliath’s size (2.9m). Talk about the different parts of his 17: 1 - 31 armour and what they were for. Talk about things that make us afraid. The Bible teaches that trusting in God can make us brave. Goliath was a giant who wanted to fight God’s people. Every day he shouted for someone to fight him. No one was brave enough. God’s people were all afraid. One day David came and saw how Goliath was frightening everyone. -

David: “A Man After God's Own Heart”

SUNDAY WORSHIP: 8:30am and 11:00am (Sanctuary) 10:45am (Ignite Modern Worship) FirstPresGreenville.org although grieving over Saul, reluctantly agrees. qualified to handle the applause of popularity. David: When he arrives and sees Eliab, Jesse’s oldest David learned that the menial, insignificant, “A Man After son, he is initially convinced that he has found routine, repetitive, unexciting tasks of daily life God’s Own Heart” the next king: “Surely the LORD’s anointed have meaning and value. It was in the everyday stands here before the LORD.” But God informs activities of life, where God was seeking 1 Samuel 16:1-13 him otherwise. As each of Jesse’s sons appear faithfulness, that David learned the value of before Samuel, God reminds him, “Man looks at monotony. the outward appearance, but the LORD looks at During this time there was no one else What Might Have Been? the heart.” around, no one to see what David was doing, Recently I spent a few hours mixing sand So what is God looking for? He is looking and no one seemed interested. Yet David and cement to repair the front steps of my for an individual whose heart is completely His. revealed responsibility and diligence in the home. They were not in great disrepair, but A person who has no locked doors or hidden little things, in the lonely places, and there he the cement between the stonework had worn compartments. Someone who believes that proved himself capable and trustworthy. During away over the years, allowing water to seep into integrity, transparency, loyalty, and faithfulness this period, David also learned that when God the gaps between the stones. -

Reconsidering the Height of Goliath in The

1 Goliath and the Exodus Giants: How tall were they? By Clyde E. Billington, Ph.D. Northwestern College INTRODUCTION Professor Daniel Hays, in his article Reconsidering the Height of Goliath in the December 2005 issue of the Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, argued that the giant Goliath, who was killed by David, was only 6 feet 9 inches tall and not 9 feet 9 inches. The key passage on the height of Goliath is I Sam 17:4-7, which reads as follows: 4. Then a champion came out from the armies of the Philistines named Goliath, from Gath, whose height was six cubits and a span. 5. He had a bronze helmet on his head, and he was clothed with scale-armor, which weighed five thousand shekels of bronze. 6. He also had bronze greaves on his legs and a bronze javelin slung between his shoulders. 7. The shaft of his spear was like a weaver‘s beam, and the head of his spear weighed six hundred shekels of iron; his shield carrier also walked before him. [NASB] The NASB quoted above, like all other English translations of the Old Testament, is based on the Masoretic Hebrew Text of I Sam 17. However, Dr. Hays in his article argues that there is a textual error, made by a sloppy or exaggerating scribe, in the height of Goliath as given in the Masoretic Text [MT]. He correctly notes that one Hebrew text [4QSama] from the Dead Sea Scrolls [DSS] and most versions of the Greek Septuagint [LXX] translation of the Old Testament give Goliath‘s height as 4 cubits and a span instead of 6 cubits and a span.1 2 According to Dr.