Hilbert-Kunz Functions of Surface Rings of Type ADE Arxiv:1604.08435V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Processing Framework and Match-Up Database MODIS Algorithm Version 3 By

Processing Framework and Match-up Database MODIS Algorithm Version 3 By Robert H. Evans University of Miami Miami, FL 33149-1098 April 30, 1999 Appendix 1 - ATBD A1.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................... 6 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 7 1.1 Algorithm and Product Identification........................................................................7 1.2 Algorithm Overview..........................................................................................7 1.3 Document Scope ..............................................................................................7 1.4 Applicable Documents and Publications .....................................................................7 2.0 OVERVIEW AND BACKGROUND INFORMATION ......................................... 7 2.1 Experimental Objective ......................................................................................7 2.2 Historical Perspective ........................................................................................8 3.0 DESCRIPTION OF ALGORITHM................................................................. 8 3.1 Introduction based on AVHRR-Oceans Pathfinder .........................................................8 Matchup Databases ..............................................................................................8 3.1.1 Global matchup databases............................................................................................................9 -

Alpine Soil Bacterial Community and Environmental Filters Bahar Shahnavaz

Alpine soil bacterial community and environmental filters Bahar Shahnavaz To cite this version: Bahar Shahnavaz. Alpine soil bacterial community and environmental filters. Other [q-bio.OT]. Université Joseph-Fourier - Grenoble I, 2009. English. tel-00515414 HAL Id: tel-00515414 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00515414 Submitted on 6 Sep 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THÈSE Pour l’obtention du titre de l'Université Joseph-Fourier - Grenoble 1 École Doctorale : Chimie et Sciences du Vivant Spécialité : Biodiversité, Écologie, Environnement Communautés bactériennes de sols alpins et filtres environnementaux Par Bahar SHAHNAVAZ Soutenue devant jury le 25 Septembre 2009 Composition du jury Dr. Thierry HEULIN Rapporteur Dr. Christian JEANTHON Rapporteur Dr. Sylvie NAZARET Examinateur Dr. Jean MARTIN Examinateur Dr. Yves JOUANNEAU Président du jury Dr. Roberto GEREMIA Directeur de thèse Thèse préparée au sien du Laboratoire d’Ecologie Alpine (LECA, UMR UJF- CNRS 5553) THÈSE Pour l’obtention du titre de Docteur de l’Université de Grenoble École Doctorale : Chimie et Sciences du Vivant Spécialité : Biodiversité, Écologie, Environnement Communautés bactériennes de sols alpins et filtres environnementaux Bahar SHAHNAVAZ Directeur : Roberto GEREMIA Soutenue devant jury le 25 Septembre 2009 Composition du jury Dr. -

Taeguturn Section

T1 I TURNING I TAEGUTHREAD PAGE T1 PAGE T176 T2 I T-CLAMP I T-CAP I TECHNICAL INDEX PAGE T224 PAGE T328 INFORMATION PAGE T362 PAGE T346 T3 T4 T5 TaeguTurn Program T8 User Guide Grades T12 Chipbreakers T16 Trouble Shooting T22 Insert Selection for Cast Iron Materials T25 Insert Geometry for Workpiece Shape T26 Insert Selection & Recommended Cutting Parameters T27 TaeguTurn Inserts Designation System T36 Negative Inserts T38 Negative KNUX Type Inserts T54 Positive Inserts T75 Inserts for Pipe Skiving T90 Inserts for Aluminum T91 Ceramic Inserts T97 CBN Inserts T106 PCD Inserts T112 T6 TaeguTurn External Toolholders & Boring Bars T117 Designation System for External Toolholders T118 Toolholder Clamping System T120 Top Clamp/External Turning Toolholders T123 Multi Lock/External Turning Toolholders T127 Screw Clamp/External Turning Toolholders T134 T-Holders - External Turning T141 Top Clamp/External Toolholders for CBN & Ceramic Inserts T150 T-Holders - External Turning for Ceramic Dimple Inserts T154 Designation System for Boring Bars T158 Top Clamp/Boring Bars T159 Multi Lock/Boring Bars T160 Lever Lock/Boring Bars T163 Screw Clamp/Boring Bars T164 T-Holders - Internal Turning T173 T-Holders - Internal Turning for Ceramic Dimple Inserts T175 T7 I TAEGUTURN PROGRAM TURNING INSERTS WS WT FA For Inserts see pages For Inserts see pages For Inserts see pages CNMG T50 CNMA T42 CNMG T45 CNMG T50 DNMG T57 DNMG T53 WNMG T78 CCMT T80 FG MC SF For Inserts see pages For Inserts see pages For Inserts see pages CNMG T45 CNMG T46 CNMG T49 DNMG T54 DNMG -

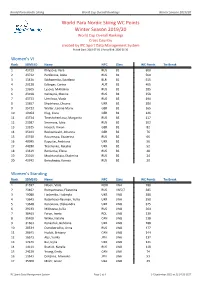

World Para Nordic Skiing WC Points Winter Season 2019/20

World Para Nordic Skiing World Cup Overall Rankings Winter Season 2019/20 World Para Nordic Skiing WC Points Winter Season 2019/20 World Cup Overall Rankings Cross Country created by IPC Sport Data Management System Period Start: 2019-07-01 | Period End: 2020-06-30 Women's VI Rank SDMS ID Name NPC Class WC Points Tie Break 1 43739 Khlyzova, Vera RUS B2 600 2 43732 Panferova, Anna RUS B2 560 3 13436 Sakhanenka, Sviatlana BLR B2 515 4 29128 Edlinger, Carina AUT B1 405 5 13605 Lysova, Mikhalina RUS B2 285 6 23918 Galitsyna, Marina RUS B1 258 7 43733 Umrilova, Vlada RUS B3 190 8 13657 Shyshkova, Oksana UKR B2 180 9 35723 Walter, Leonie Maria GER B2 165 10 19064 Klug, Clara GER B1 126 11 43734 Tereshchenkova, Margarita RUS B3 117 12 23987 Smirnova, Iuliia RUS B2 102 13 13525 Hoesch, Vivian GER B1 82 14 35103 Recktenwald, Johanna GER B2 76 15 43740 Razumnaia, Ekaterina RUS B2 66 16 40995 Kapustei, Andriana UKR B2 56 17 44280 Tkachenko, Nataliia UKR B2 52 18 13619 Remizova, Elena RUS B3 48 19 23919 Moshkovskaia, Ekaterina RUS B2 24 20 43742 Berezhnaia, Kseniia RUS B2 20 Women's Standing Rank SDMS ID Name NPC Class WC Points Tie Break 1 31597 Nilsen, Vilde NOR LW4 780 2 23402 Rumyantseva, Ekaterina RUS LW5/7 385 3 19080 Liashenko, Liudmyla UKR LW8 380 4 13643 Batenkova-Bauman, Yuliia UKR LW6 350 5 13648 Kononova, Oleksandra UKR LW8 325 6 29233 Mikheeva, Iuliia RUS LW8 264 7 30463 Faron, Iweta POL LW8 239 8 35400 Wilkie, Natalie CAN LW8 238 9 31663 Konashuk, Bohdana UKR LW8 188 10 20534 Ostroborodko, Anna RUS LW8 177 11 20641 Hudak, Brittany CAN -

All 12 Wcha Men's-Member Teams to Engage in League

WESTERN COLLEGIATE HOCKEY ASSOCIATION Bruce M. McLeod Commissioner Carol LaBelle-Ehrhardt Assistant Commissioner of Operations Greg Shepherd Supervisor of Officials Administrative Office Western Collegiate Hockey Association November 26, 2012/For Immediate Release 2211 S. Josephine Street, Room 302 Denver, CO 80210 ALL 12 WCHA MEN’S-MEMBER TEAMS TO ENGAGE IN LEAGUE p: 303 871-4491. f: 303 871-4770 [email protected] PLAY NOVEMBER 30-DECEMBER 1 … IT’S UMD AT MTU, UNO AT Doug Spencer Associate Commissioner for UM, BSU AT MSU, UW AT DU, UND AT CC, SCSU AT UAA Public Relations MINNESOTA STATE GAINS THANKSGIVING WCHA SWEEP AT UW; BEMIDJI STATE EARNS THREE Western Collegiate Hockey Association 559 D’Onofrio Drive, Ste. 103 POINTS FROM UAA; SCSU SPLITS AT UMD; WEEKEND RESULTS SEE MINNESOTA SWEEP AT Madison, WI 53719-2096 VERMONT, HOST NEBRASKA OMAHA DOWN UAH TWICE AS LEAGUE TEAMS GO 5-4-1 IN NON- p: 608 829-0100. f: 608 829-0200 [email protected] CONFERENCE PLAY; GOPHERS, UNO MAVERICKS UNBEATEN OVER LAST SIX; LATEST DIVISION 1 MEN’S NATIONAL POLLS HAVE UM NO. 3, DU NO. 5, UND NO. 7/8, UNO NO. 13/14, SCSU NO. HOME OF A COLLEGIATE RECORD 37 14/15, CC NO. 18 … MSU RECEIVES VOTES MEN’S NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP TEAMS SINCE 1951 MADISON, Wis. – The first of two consecutive weekends that will feature all 12 Western Collegiate Hockey 1952, 1953, 1955, 1956, 1957, 1958, 1959, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, Association men’s-member teams engaged in conference play will occur this Friday and Saturday, Nov. 1965, 1966, 1968, 1969, 1973, 1974, 30 and Dec. -

Athletics Classification Rules and Regulations 2

IPC ATHLETICS International Paralympic Committee Athletics Classifi cation Rules and Regulations January 2016 O cial IPC Athletics Partner www.paralympic.org/athleticswww.ipc-athletics.org @IPCAthletics ParalympicSport.TV /IPCAthletics Recognition Page IPC Athletics.indd 1 11/12/2013 10:12:43 Purpose and Organisation of these Rules ................................................................................. 4 Purpose ............................................................................................................................... 4 Organisation ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Article One - Scope and Application .................................................................................. 6 International Classification ................................................................................................... 6 Interpretation, Commencement and Amendment ................................................................. 6 2 Article Two – Classification Personnel .............................................................................. 8 Classification Personnel ....................................................................................................... 8 Classifier Competencies, Qualifications and Responsibilities ................................................ 9 3 Article Three - Classification Panels ................................................................................ 11 4 Article Four -

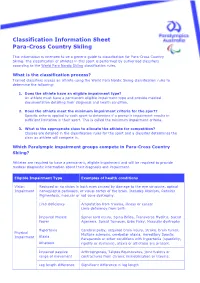

Classification Information Sheet Para-Cross Country Skiing

Classification Information Sheet Para-Cross Country Skiing This information is intended to be a generic guide to classification for Para-Cross Country Skiing. The classification of athletes in this sport is performed by authorised classifiers according to the World Para Nordic Skiing classification rules. What is the classification process? Trained classifiers assess an athlete using the World Para Nordic Skiing classification rules to determine the following: 1. Does the athlete have an eligible impairment type? An athlete must have a permanent eligible impairment type and provide medical documentation detailing their diagnosis and health condition. 2. Does the athlete meet the minimum impairment criteria for the sport? Specific criteria applied to each sport to determine if a person’s impairment results in sufficient limitation in their sport. This is called the minimum impairment criteria. 3. What is the appropriate class to allocate the athlete for competition? Classes are detailed in the classification rules for the sport and a classifier determines the class an athlete will compete in. Which Paralympic impairment groups compete in Para-Cross Country Skiing? Athletes are required to have a permanent, eligible impairment and will be required to provide medical diagnostic information about their diagnosis and impairment. Eligible Impairment Type Examples of health conditions Vision Reduced or no vision in both eyes caused by damage to the eye structure, optical Impairment nerves/optic pathways, or visual cortex of the brain. Includes -

IPC Alpine Skiing Classification Rules and Regulations

IPC Alpine Skiing Classification Rules and Regulations 05 December 2012 International Paralympic Committee Adenauerallee 212-214 Tel.+49 228 2097-200 www.paralympic.org 53113 Bonn, Germany Fax+49 228 2097-209 [email protected] Content 1 INTRODUCTION TO CLASSIFICATION ..................................................................................................... 4 1.1 GOVERNANCE ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 STRUCTURE OF CLASSIFICATION REGULATIONS .................................................................................................................. 4 1.3 PURPOSE OF CLASSIFICATION REGULATIONS ..................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 IPC CLASSIFICATION CODE ........................................................................................................................................... 5 1.5 DEFINITIONS ............................................................................................................................................................. 5 2 CLASSIFIERS .......................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 CLASSIFICATION PERSONNEL ......................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 CLASSIFIERS – LEVELS -

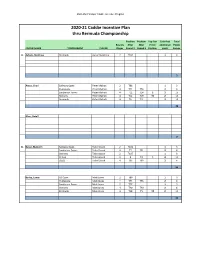

2020-2021 Valspar Points Thru Bermuda Championship

2020-2021 Valspar Caddie Incentive Program 2020-21 Caddie Incentive Plan thru Bermuda Championship Position Position Top Ten Color hat Total Rounds After After Finish additional Points CADDIE NAME TOURNAMENT PLAYER Played Round 2 Round 3 Position points Earned A- Achatz, Matthew Bermuda Aaron Baddeley 2 T102 1 3 3 Antus, Chad Safeway Open Peter Malnati 2 T86 1 3 Puntacana Peter Malnati 4 T21 T24 2 6 Sanderson Farms Peter Malnati 4 T12 T14 2 2 15 Shriners Peter Malnati 4 T12 T19 T5 2 15 Bermuda Peter Malnati 4 T6 T11 2 10 49 Aton, Derell 0 B- Baker, Malcolm Safeway Open Talor Gooch 2 T101 1 3 Sanderson Farms Talor Gooch 4 T7 T31 2 8 Shriners Talor Gooch 2 T107 1 3 CJ Cup Talor Gooch 4 4 T2 5 2 15 ZOZO Talor Gooch 4 T35 T39 2 6 35 Bailey, Lance US Open Matt Jones 2 T89 1 3 Puntacana Matt Jones 4 T44 T45 2 6 Sanderson Farms Matt Jones 2 T77 1 3 Shriners Matt Jones 4 T40 T40 2 6 Bermuda Matt Jones 4 T18 T5 T4 2 15 33 2020-2021 Valspar Caddie Incentive Program Bennett, Lance Safeway Open Luke List 4 T54 T49 2 6 6 Berry, Chris Shriners Brian Gay 2 T81 2 2 Billskoog, Victor 0 2020-2021 Valspar Caddie Incentive Program Bradley, Kyle Safeway Open Hudson Swafford 4 T34 T58 4 Puntacana Hudson Swafford 4 1 2 Win 18 Sanderson Farms Hudson Swafford 2 T110 2 Shriners Hudson Swafford 2 142 2 Bermuda Hudson Swafford 4 T48 T48 4 30 Brennan, Mick Safeway Open Matthew NeSmith 2 T108 1 3 Puntacana Matthew NeSmith 4 T44 T55 2 6 Sanderson Farms Matthew NeSmith 4 T24 T14 2 8 Shriners Matthew NeSmith 4 T40 T14 T8 2 13 30 Brittain, Boston Safeway Open Kelly Kraft -

World Para Alpine Skiing Rules and Regulations

World Para Alpine Skiing Rules and Regulations 2018/2019 August 2018 World Para Alpine Skiing Rules and Regulations For Alpine Skiing: Downhill, Super-G, Super Combined, Giant Slalom, Slalom, & Team Events 2018-2019 Season – valid until 1 October 2019 World Para Alpine Skiing Rules and Regulations: Competition Season 2018-2019 1 Contents Section 1: Regulations 300 Joint Regulations for World Para Alpine Skiing (WPAS) 301 WPAS Competitions 302 World Cup (Level 0) and Europa Cup, NORAM (Level 1) Point System, Rankings and Trophies 303 World Para Alpine Skiing Calendar 304 World Para Alpine Skiing Race Licence (WPAS Licence) 305 Race Licence Pre-requisites 306 Competitor’s Obligations and Rights 307 Sponsorships and Advertising 308 Display of Competition Equipment 309 Organisation of Competition 310 Invitation/Programme 311 Competition Administration and Fee Regulations (Athletes and Organising Committees) 312 Competition Entries 313 Team Captains’ Meetings 314 Draw 315 Start List / Publication of Results 316 Competitor Medical Examinations and Compliance with the IPC Anti-Doping Code 317 Medical Services Required from Event Organisers 318 Competition Equipment 319 Equipment Controls 320 Gambling and Competitions 321 Sanctions 322 Procedural Guidelines 323 Protests 324 Place of Submission World Para Alpine Skiing Rules and Regulations: Competition Season 2018-2019 2 325 Deadlines for Submission 326 Form of Protests 327 Protest Fees 328 Authorisation 329 Settlement of Protests by the Jury 330 Appeals Section 2: Rules Common to All Alpine Skiing -

ATHLETICS Medal Events Male Female Mixed Total 93 74 1 (Universal Relay) 168 Detailed Medal Events List at the End of This Chapter

ATHLETICS Medal Events Male Female Mixed Total 93 74 1 (Universal Relay) 168 Detailed Medal Events List at the end of this chapter Athlete Quota Male Female Gender Free Total 630 470 0 1100 Allocation of Qualification Slots An athlete may only obtain a maximum of one qualification slot. The qualification slot is allocated to the NPC not to the individual athlete. In case of a Bipartite Commission Invitation the slot is allocated to the individual athlete not to the NPC. Maximum Quota Allocation per NPC An NPC can be allocated a maximum of forty-five (45) male qualification slots and thirty-five (35) female qualification slots. Exceptions may be granted through the Bipartite Commission Invitation Allocation method. If an NPC is unable to use all of the allocated qualification slots in a given gender, the unused slots cannot be transferred to the other gender. They will be reallocated in the respective gender to other NPCs through the Bipartite Invitation Commission Allocation method. Athlete Eligibility To be eligible for selection by an NPC, athletes must: . hold an active World Para Athletics Athlete Licence for the 2020 season; . have achieved one (1) Minimum Entry Standard (MES) performance at a World Para Athletics Recognised Competition (IPC Competition, WPA Sanctioned Competition, or WPA Approved Competition) for each of their respective events between 1 October 2018 and 2 August 2020 in accordance with the IPC Athlete Licensing Programme Policies valid Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games – Qualification Regulations Athletics for the 2018-2020 seasons – exceptions may be made via the Bipartite Commission Invitation Allocation method; and . -

World Para Alpine Skiing WC Points Winter Season 2013/14

World Para Alpine Skiing World Cup Overall Rankings Winter Season 2013/14 World Para Alpine Skiing WC Points Winter Season 2013/14 World Cup Overall Rankings created by IPC Sport Data Management System Period Start: 2013-07-01 | Period End: 2014-06-30 Women's VI Rank SDMS ID Name NPC Class WC Points Tie Break 1 13418 Umstead, Danelle USA B2 1200 2 13286 Frantseva, Aleksandra RUS B2 1140 3 12946 Perrine, Melissa AUS B2 905 4 13140 Gallagher, Kelly GBR B3 720 5 13139 Etherington, Jade GBR B2 705 6 13349 Farkasova, Henrieta SVK B3 680 7 2142 Gallagher, Jessica AUS B3 440 8 14237 Mannella, Staci USA B3 385 9 13350 Kozickova, Petra SVK B3 230 10 16125 Yang, Jae Rim KOR B2 60 11 13414 Sarubbi, Caitlin USA B3 40 Women's Standing Rank SDMS ID Name NPC Class WC Points Tie Break 1 13116 Bochet, Marie FRA LW6/8-2 1460 2 13162 Rothfuss, Andrea GER LW6/8-2 1220 3 13288 Medvedeva, Inga RUS LW2 1072 4 13408 Jones, Allison USA LW2 875 5 13291 Papulova, Mariia RUS LW6/8-2 727 6 13261 Jochemsen, Anna NED LW2 577 7 13351 Smarzova, Petra SVK LW6/8-2 476 8 13407 Jallen, Stephanie USA LW9-1 353 9 13086 Pueyo Marimon, Ursula ESP LW2 350 10 13035 Starker, Alexandra CAN LW6/8-2 310 11 13119 Jambaque, Solene FRA LW9-2 287 12 13034 Schwartz, Melanie USA LW2 240 13 13274 Valeanu, Laura ROU LW4 150 14 19058 Latimer, Erin CAN LW6/8-2 127 15 13206 Corradini, Melania ITA LW6/8-1 120 16 14412 Mills, Heather GBR LW4 80 17 13032 Ramsay, Alana CAN LW9-2 72 IPC Sport Data Management System Page 1 of 4 26 September 2021 at 22:37:42 CEST World Para Alpine Skiing World Cup Overall