Eighteenth, Century Changes in Hampshire Chalkland Farming by E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Week Ending 12Th February 2010

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 06 Week Ending: 12th February 2010 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column For the Northern Area to: For the Southern Area to: Head of Planning Head of Planning Beech Hurst Council Offices Weyhill Road Duttons Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ ROMSEY SO51 8XG In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 10/00166/FULLN Erection of two replacement 33 And 34 Andover Road, Red Mr & Mrs S Brown Jnr Mrs Lucy Miranda YES 08.02.2010 dwellings together with Post Bridge, Andover, And Mr R Brown Page ABBOTTS ANN garaging and replacement Hampshire SP11 8BU 12.03.2010 and resiting of entrance gates 10/00248/VARN Variation of condition 21 of 11 Elder Crescent, Andover, Mr David Harman Miss Sarah Barter 10.02.2010 TVN.06928 - To allow garage Hampshire, SP10 3XY 05.03.2010 ABBOTTS ANN to be used for storage room -

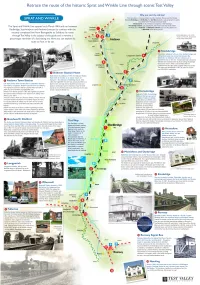

Sprat and Winkle Line Leaflet

k u . v o g . y e l l a v t s e t @ e v a e l g d t c a t n o c e s a e l P . l i c n u o C h g u o r o B y e l l a V t s e T t a t n e m p o l e v e D c i m o n o c E n i g n i k r o w n o s n i b o R e l l e h c i M y b r e h t e g o t t u p s a w l a i r e t a m e h T . n o i t a m r o f n I g n i d i v o r p r o f l l e s d n i L . D r M d n a w a h s l a W . I r M , n o t s A H . J r M , s h p a r g o t o h p g n i d i v o r p r o f y e l r e s s a C . R r M , l l e m m a G . C r M , e w o c n e l B . R r M , e n r o H . M r M , e l y o H . R r M : t e l f a e l e l k n i W d n a t a r p S e h t s d r a w o t n o i t a m r o f n i d n a s o t o h p g n i t u b i r t n o c r o f g n i w o l l o f e h t k n a h t o t e k i l d l u o w y e l l a V t s e T s t n e m e g d e l w o n k c A . -

Week Ending 9Th September 2016

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 36 Week Ending: 9th September 2016 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column Head of Planning and Building Beech Hurst Weyhill Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 16/02137/FULLN Two storey extension to Ash Cottage , 37 Duck Street, Mr And Mrs Bill And Mr Craig Morrison YES 09.09.2016 garden with ground floor Abbotts Ann, SP11 7AZ Michelle Pelling 07.10.2016 ABBOTTS ANN family room and first floor bedroom and en-suite. 16/02138/LBWN Two storey extension to Ash Cottage , 37 Duck Street, Mr And Mrs Bill And Mr Craig Morrison YES 09.09.2016 garden with ground floor Abbotts Ann, SP11 7AZ Michelle Pelling 07.10.2016 ABBOTTS ANN family room and first floor bedroom and en-suite; new French doors leading from existing snug to garden. 16/02151/TPON T3 Filed Maple - Crown 9 Abbotts Hill, Little Ann, Mr Per Sabroe Amelia Williams 09.09.2016 reduce by 4m in height and Andover, Hampshire SP11 7PJ 03.10.2016 ABBOTTS ANN reshape. 16/02195/TREEN Tree of Heaven - Reduce Upper Cottage, Monxton Road, Mr David Paffett Amelia Williams 06.09.2016 overhanging branch by 1/3 Abbotts Ann, Andover 28.09.2016 ABBOTTS ANN Hampshire SP11 7BA 16/01755/TPON 1x Silver Birch - Dismantle to 21 Eardley Avenue, Andover, Mr Albert James Amelia Williams 08.09.2016 ground. -

Parish Churches of the Test Valley

to know. to has everything you need you everything has The Test Valley Visitor Guide Visitor Valley Test The 01264 324320 01264 Office Tourist Andover residents alike. residents Tourist Office 01794 512987 512987 01794 Office Tourist Romsey of the Borough’s greatest assets for visitors and and visitors for assets greatest Borough’s the of villages and surrounding countryside, these are one one are these countryside, surrounding and villages ensure visitors are made welcome to any of them. of any to welcome made are visitors ensure of churches, and other historic buildings. Together with the attractive attractive the with Together buildings. historic other and churches, of date list of ALL churches and can offer contact telephone numbers, to to numbers, telephone contact offer can and churches ALL of list date with Bryan Beggs, to share the uniqueness of our beautiful collection collection beautiful our of uniqueness the share to Beggs, Bryan with be locked. The Tourist Offices in Romsey and Andover hold an up to to up an hold Andover and Romsey in Offices Tourist The locked. be This leaflet has been put together by Test Valley Borough Council Council Borough Valley Test by together put been has leaflet This church description. Where an is shown, this indicates the church may may church the indicates this shown, is an Where description. church L wide range of information to help you enjoy your stay in Test Valley. Valley. Test in stay your enjoy you help to information of range wide every day. Where restrictions apply, an is indicated at the end of the the of end the at indicated is an apply, restrictions Where day. -

Historic Environment Action Plan West Wight Chalk Downland

Directorate of Community Services Director Sarah Mitchell Historic Environment Action Plan West Wight Chalk Downland Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service October 2008 01983 823810 archaeology @iow.gov.uk Iwight.com HEAP for West Wight Chalk Downland. INTRODUCTION The West Wight Chalk Downland HEAP Area has been defined on the basis of geology, topography and historic landscape character. It forms the western half of a central chalk ridge that crosses the Isle of Wight, the eastern half having been defined as the East Wight Chalk Ridge . Another block of Chalk and Upper Greensand in the south of the Isle of Wight has been defined as the South Wight Downland . Obviously there are many similarities between these three HEAP Areas. However, each of the Areas occupies a particular geographical location and has a distinctive historic landscape character. This document identifies essential characteristics of the West Wight Chalk Downland . These include the large extent of unimproved chalk grassland, great time-depth, many archaeological features and historic settlement in the Bowcombe Valley. The Area is valued for its open access, its landscape and wide views and as a tranquil recreational area. Most of the land at the western end of this Area, from the Needles to Mottistone Down, is open access land belonging to the National Trust. Significant historic landscape features within this Area are identified within this document. The condition of these features and forces for change in the landscape are considered. Management issues are discussed and actions particularly relevant to this Area are identified from those listed in the Isle of Wight HEAP Aims, Objectives and Actions. -

Planning Services

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 47 Week Ending: 23rd November 2018 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column Head of Planning and Building Beech Hurst Weyhill Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 18/03025/TREEN Fell Fir Tree encroaching on Pollyanna, Little Ann Road, Mr Patrick Roberts Mr Rory Gogan YES 19.11.2018 Cherry tree; T1 Ash and T2 Little Ann, Andover Hampshire 21.12.2018 ABBOTTS ANN Ash both showing signs of SP11 7SN desease and some dieback (see full description on form) 18/03018/FULLN Change of use from Telford Gate, Unit 1 , Mr Ricky Sumner, RSV Mr Luke Benjamin 19.11.2018 factory/warehouse to general Hopkinson Way, Portway Services 12.12.2018 ANDOVER TOWN industrial to include vehicle Business Park, Andover SP10 (HARROWAY) repairs and servicing and 3SF MOT testing 18/03067/CLEN -

Nether Wallop Stockbridge

NETHER WALLOP STOCKBRIDGE PRICE GUIDE £1,000,000 www.penyards.com www.primelocation.com www.rightmove.co.uk www.onthemarket.com www.mayfairoffice.co.uk HILL FARM BENT STREET, NETHER WALLOP, STOCKBRIDGE, HAMPSHIRE SO20 8EJ A rare opportunity to purchase a superb equestrian facility positioned within a site of approximately 9.5 acres with sumptuous views, located in the sought after village of Nether Wallop. DESCRIPTION SUMMARY OF ACCOMMODATION Positioned off a quiet lane in the unspoilt, To one side, and hidden from the house there GROUND FLOOR picturesque Test Valley, the property is is a prodigious stable block with 12 boxes, • Sitting room surrounded by wonderful countryside and, formerly used to stable race horses. • Dining room along with its paddocks and stabling, is ideally • Conservatory set up for the equestrian enthusiast. There is An additional block offers 3 further boxes. • Kitchen also abundant outriding in the vicinity. The And there is yet another brick built outbuilding • WC property offers great versatility and scope for which once housed the stables’ office. The refurbishment and will appeal therefore to a entire plot totals approximately 9.5 acres. FIRST FLOOR wide range of prospective buyers wishing to • Master bedroom enjoy rural village life but with the convenience SITUATION • Two further double bedrooms of excellent commuter links and well regarded The village of Nether Wallop lies in the Test • Family bathroom schooling for all ages. Valley just north of the A30 between Stockbridge and Salisbury. The attractive Edwardian house comprises on FEATURES the ground floor a sitting room with open The village is renowned for its many beautiful • Attractive Edwardian façade fireplace, dining room, kitchen, cloakroom and period buildings, Saxon Church and the Wallop • Double garage a lovely spacious conservatory looking out onto Brook, a tributary of the River Test. -

Downland Mosaic Large Scale Found Throughout the Hampshire Downs, but Most Extensive in Mid and North Hampshire

LANDSCAPE CHARACTER TYPE: Downland Mosaic Large Scale Found throughout the Hampshire Downs, but most extensive in mid and north Hampshire. SIMILAR AND ASSOCIATED TYPES HAMPSHIRE DISTRICT AND BOROUGH LEVEL ASSESSMENTS Basingstoke: Primary association: Semi Enclosed Chalk and Clay Farmland, Enclosed Chalk and Clay Farmland large Scale. Secondary association: Open Arable, Parkland and Estate Farmland East Hampshire Downland Mosaic Open Eastleigh n/a Fareham n/a Gosport n/a Hart Enclosed Arable Farmland Havant n/a New Forest n/a Rushmoor n/a Test Valley Enclosed Chalk and Clay Woodland (where woodlands are large and extensive) Winchester Primary association: Chalk and Clay Farmland Secondary association: Scarp Downland Grassland and some Chalk and Clay Woodland SIMILAR AND ASSOCIATED TYPES IN NEIGHBOURING AUTHORITY ASSESSMENTS Dorset West Berkshire West Sussex Wiltshire Hampshire County 1 Status: FINAL Draft Autumn 2010 Integrated Character Assessment Downland Mosaic Large Scale KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS AND BOUNDARY DEFINITIONS A Downs landscape which has moderately heavy soils and more clay soil content than in Open Downs landscapes. Can have mini scarps which are individually identified in some local assessments. Large scale character influenced by rolling topography, medium to large size fields, fewer wooded hedges than the small scale type and can have large woodland blocks. Large blocks of ancient woodland and varied height hedgerow network which contrasts with areas of more open predominantly arable fields. Deeply rural quiet landscapes with sense of space and expansiveness uninterrupted by development the large woodland blocks add to the sense ruralness and of an undeveloped landscape. Low density road and lane network where this type occurs in mid and west Hampshire –higher density further east. -

Detached Family Home in Popular Test Valley Village

DETACHED FAMILY HOME IN POPULAR TEST VALLEY VILLAGE greenleas, five bells lane, nether wallop, stockbridge, hampshire so20 8en DETACHED FAMILY HOME IN POPULAR TEST VALLEY VILLAGE greenleas, five bells lane, nether wallop, stockbridge, hampshire so20 8en Sitting room � Dining room � Kitchen/breakfast room � Study � Main bedroom with en suite � 3 further bedrooms � Family bathroom � Garage � Garden � EPC = E Situation Nether Wallop is situated on the edge of the Test Valley, one of three renowned Hampshire villages that are known as The Wallops. Within the village is a church, whilst in neighbouring Over Wallop there is a village shop/post office. The nearby market town of Stockbridge offers a wide range of boutique shops, restaurants and pubs as well as a hotel and reputable butcher. The cathedral cities of Salisbury to the west and Winchester to the east provide more comprehensive recreational, shopping and educational facilities. Leisure activities close by include racing at Salisbury; fishing on the River Test and its carriers; golf at the Test Valley Golf Club at Andover; sailing on the Solent; concerts at Broadlands, Romsey; and extensive riding and walking in the immediate area. Grateley station is approximately 4 miles away, providing a fast and regular train service to London Waterloo throughout the day. Further afield at Andover there is a regular rail service to London Waterloo taking approximately 70 minutes, and Winchester with rail services to London in an hour. Description Greenleas is a brick built detached property which was constructed in 1986. The accommodation is conventionally arranged over two floors and offers good family accommodation. -

King's Somborne Footpath Walks 2014

King’s Somborne Footpath Walks 2014 The programme of footpath walks listed below is as of 1 January 2014 and may be subject to change throughout the year. Please refer to the village website (www.thesombornes.org.uk – Directory – Footpath Walk) for the latest information. Sunday 26 January 2014 2:00pm King’s Somborne Village Hall 5½ miles (8¾ Km) 2¼ hours We leave the village along Winchester Road and up Red Hill before turning onto the path past Ashley New buildings. At the crossroads we take the path across the field past Ashley Manor Farm and then over the hill to Chalk Vale before returning to the village past the beef unit and back along Winchester Road. Sunday 23 February 2014 2:00pm King’s Somborne Village Hall 4¾ miles (7½ Km) 2 hours We cross Palace Field and alongside the churchyard to pick up the Clarendon Way alongside Cow Drove Hill. We follow the Clarendon Way past How Park and across the water meadows to Houghton. From Houghton, it is road walking past the site of Bossington village before taking the footpath along the line of the Roman road to Horsebridge and the footpath back to the village. Sunday 30 March 2014 2:00 pm King’s Somborne Village Hall 6 miles (9½ Km) 2½ hours We leave the village along Winchester Road and take the path past the Beef Unit. We continue towards Up Somborne before turning left to take the steep path down to Little Somborne. At Little Somborne we head North to North Park Farm and the path back towards the village. -

Luton SUE Site Size (Ha): 283.81

Site: NLP426 - North Luton SUE Site size (ha): 283.81 Parcel: NLP426f Parcel area (ha): 89.74 Stage 1 assessment Stage 2 assessment Parcel: L2 Parcel: n/a Highest contribution: Purpose 3 - Strong Contribution: contribution Contribution to Green Belt purposes Purpose Comments Purpose 1: Checking The parcel is located adjacent to the large built up area and development here would relate the unrestricted to the expansion of Luton. The parcel is only separated from the settlement edge to the sprawl of large, built- south by occasional hedgerow trees. However, the low hedgerows, and intermittent up areas hedgerow trees along the remaining boundaries provide little separation between the parcel and the rolling farmland beyond the parcel to the north, west and east, so that despite its proximity to Luton, the parcel relates more strongly to the wider countryside and its release would constitute significant sprawl into the countryside. Purpose 2: The development of the parcel would result in little perception of the narrowing of the gap Preventing the between neighbouring towns because the larger towns to the north of Luton, including merger of Flitwick, are separated by the chalk escarpment running east-west which would limit the neighbouring towns impact. Purpose 3: The proximity of the adjacent residential settlement edge has some urbanising influence on Safeguarding the the parcel particularly as the occasional hedgerow trees on the boundary offer little countryside from separation. However, there is no urban development within the parcel itself and openness encroachment and undulating topography of the parcel give it a stronger relationship with the wider downland countryside. -

HEAP for Isle of Wight Rural Settlement

Isle of Wight Parks, Gardens & Other Designed Landscapes Historic Environment Action Plan Isle of Wight Gardens Trust: March 2015 2 Foreword The Isle of Wight landscape is recognised as a source of inspiration for the picturesque movement in tourism, art, literature and taste from the late 18th century but the particular significance of designed landscapes (parks and gardens) in this cultural movement is perhaps less widely appreciated. Evidence for ‘picturesque gardens’ still survives on the ground, particularly in the Undercliff. There is also evidence for many other types of designed landscapes including early gardens, landscape parks, 19th century town and suburban gardens and gardens of more recent date. In the 19th century the variety of the Island’s topography and the richness of its scenery, ranging from gentle cultivated landscapes to the picturesque and the sublime with views over both land and sea, resulted in the Isle of Wight being referred to as the ‘Garden of England’ or ‘Garden Isle’. Designed landscapes of all types have played a significant part in shaping the Island’s overall landscape character to the present day even where surviving design elements are fragmentary. Equally, it can be seen that various natural components of the Island’s landscape, in particular downland and coastal scenery, have been key influences on many of the designed landscapes which will be explored in this Historic Environment Action Plan (HEAP). It is therefore fitting that the HEAP is being prepared by the Isle of Wight Gardens Trust as part of the East Wight Landscape Partnership’s Down to the Coast Project, particularly since well over half of all the designed landscapes recorded on the Gardens Trust database fall within or adjacent to the project area.