A Thesis on the Authenticity and Preservation of Functionally-Used Objects Joshua Karl Sundermeyer a Thesis Submitted in Partial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release

Press release Zurich/Geneva, 17 April 2019 Global Powers of Luxury Goods: Swiss luxury companies are taking the digital path to accelerate growth • The sales of the world’s Top 100 luxury goods companies grew by 11% and generated aggregated revenues of USD 247 billion in fiscal year 2017 • Richemont, Swatch Group and Rolex remain in the top league of Deloitte’s Global Powers of Luxury Goods ranking • All Swiss companies in the Top 100 returned to growth in FY2017, but with only 8% increase, they lagged behind the whole market for the third time in a row • Luxury goods companies are making significant investments in digital marketing and the use of social media to engage their customers Despite the recent slowdown of economic growth in major markets including China, the Eurozone and the US, the luxury goods market looks positive. In FY2017, the world’s Top 100 luxury goods companies generated aggregated revenues of USD 247 billion, representing composite sales growth of 10.8%, according to Deloitte’s 2019 edition of Global Powers of Luxury Goods. For comparison, in FY2016 sales were USD 217 billion and annual sales growth was as low as 1.0%. Three-fourth of the companies (76%) reported growth in their luxury sales in FY2017, with nearly half of these recording double-digit year-on-year growth. Switzerland and Hong Kong prevail in the luxury watches sector Looking at product sectors, clothing and footwear dominated again in FY2017, with a total of 38 companies. The multiple luxury goods sector represented the largest sales share (30.8%), narrowly followed by jewellery and watches (29.6%). -

New Twenty~4 Models Is Accompanied by a Digital Communication Campaign Addressing Modern Women Sure of Their Taste, with an Affinity for Beauty and Fine Design

Press release Patek Philippe, Geneva October 2020 A new face for the Twenty~4, the Patek Philippe ladies’ watch born to accompany every moment of the modern woman’s life The manufacture is stepping up the allure of its Twenty~4 collection exclusively for women with a fresh interpretation of the original “manchette” or cuff-style quartz model in steel of 1999. It is launching two new versions adorned with white-gold applied Arabic numerals and white-gold applied trapeze-shaped hour markers. Designed as stylish companions to every facet of an active lifestyle, these Twenty~4 references 4910/1200A- 001 with a blue sunburst dial and 4910/1200A-010 with a gray sunburst dial stand out more than ever as paragons of timeless feminine elegance. Since 1839, timepieces for women have always featured prominently in Patek Philippe’s collections – whether as the pocket watches or pendant watches of the nineteenth century or the wristwatches that first emerged in the early twentieth century. Several milestones in the manufacture’s history also relate to watches destined for women, such as the first true wristwatch made in Switzerland, created for a Hungarian countess in 1868, and the Geneva company’s very first striking wristwatch, a five-minute repeater housed in a small platinum case with an integrated chain bracelet in 1916. A modern classic In 1999, Patek Philippe strengthened its privileged links with feminine watch lovers by launching its first collection dedicated exclusively to women. The aim was to meet the demands of the independent active woman who sought a timepiece with an assertive personality able to adapt to her modern lifestyle. -

Deloitte Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2018

Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2018 Shaping the future of the luxury industry Contents Foreword 3 Top 100 quick statistics 4 Shaping the future of the luxury industry 5 Global Economic Outlook 9 Top 100 highlights 13 Global Powers of Luxury Goods Top 100 15 Top 10 highlights 23 Fastest 20 27 Product sector analysis 29 Geographic analysis 37 Newcomers 45 Study methodology and data sources 47 Endnotes 50 Contacts 51 Luxury goods in this report focuses on luxury for personal use, and is the aggregation of designer clothing and footwear (ready-to-wear), luxury bags and accessories (including eyewear), luxury jewellery and watches and premium cosmetics and fragrances. Foreword Welcome to the fifthGlobal Powers of Luxury Goods. The report examines and lists the 100 largest luxury goods companies globally, based on the consolidated sales of luxury goods in FY2016 (which we define as financial years ending within the 12 months to 30 June 2017). It also discusses the key trends shaping the luxury market and provides a global economic outlook. The world’s 100 largest luxury goods companies generated personal luxury goods sales of US$217 billion in FY2016. At constant currency, the growth rate was 1 per cent, 5.8 percentage points lower than the 6.8 per cent currency-adjusted growth achieved by these companies in the previous year. The average luxury goods annual sales for a Top 100 company is now US$2.2 billion. The luxury market has bounced back from economic uncertainty and geopolitical crises, edging closer to annual sales of US $1 trillion at the end of 2017. -

The Authorized Biography the Definitive History of the Legendary Swiss Manufacture

Press release Patek Philippe SA Geneva November 2016 Patek Philippe: The Authorized Biography The definitive history of the legendary Swiss manufacture Written by Nicholas Foulkes, an acclaimed specialist in art and horology, and spanning over 500 pages, this work describes the evolution of the independent Genevan manufacture from its beginnings in 1839 to the present. The English edition is being released in November and will be followed by other languages as of 2018. Drawing on exclusive interviews with the company’s owners and with staff and watchmakers past and present, as well as on hitherto unseen documents from the company’s archives, Patek Philippe: The Authorized Biography celebrates the history of a unique company. Renowned historian, author, and editor Nicholas Foulkes traces Patek Philippe’s history from founder Antoine Norbert de Patek’s early life in Poland as a young cavalry officer fighting in a doomed uprising. He recounts Patek’s exile, his life in Geneva, his meeting with gifted watchmaker Jean Adrien Philippe, and the 1932 purchase of the company by the Stern family, whose members, over four generations, have turned it into the legend that it is today. His vibrant narrative pays tribute not only to the creations of the Genevan manufacture but also to the gifted individuals who forged its history – especially to the many generations of watchmakers and artisans who can take credit for its success. Among other notable anecdotes, The Authorized Biography reveals, for the first time, the story of a unique timepiece bought by Queen Victoria for her husband Prince Albert. In addition, Nicholas Foulkes was granted privileged access to interview the widow of famed Swiss jewelry designer Gerald Genta, who was responsible for the design of the first Nautilus model in 1976. -

Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2018 Shaping the Future of the Luxury Industry Contents

Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2018 Shaping the future of the luxury industry Contents Foreword 3 Top 100 quick statistics 4 Shaping the future of the luxury industry 5 Global Economic Outlook 9 Top 100 highlights 13 Global Powers of Luxury Goods Top 100 15 Top 10 highlights 23 Fastest 20 27 Product sector analysis 29 Geographic analysis 37 Newcomers 45 Study methodology and data sources 47 Endnotes 50 Contacts 51 Luxury goods in this report focuses on luxury for personal use, and is the aggregation of designer clothing and footwear (ready-to-wear), luxury bags and accessories (including eyewear), luxury jewellery and watches and premium cosmetics and fragrances. Foreword Welcome to the fifthGlobal Powers of Luxury Goods. The report examines and lists the 100 largest luxury goods companies globally, based on the consolidated sales of luxury goods in FY2016 (which we define as financial years ending within the 12 months to 30 June 2017). It also discusses the key trends shaping the luxury market and provides a global economic outlook. The world’s 100 largest luxury goods companies generated personal luxury goods sales of US$217 billion in FY2016. At constant currency, the growth rate was 1 per cent, 5.8 percentage points lower than the 6.8 per cent currency-adjusted growth achieved by these companies in the previous year. The average luxury goods annual sales for a Top 100 company is now US$2.2 billion. The luxury market has bounced back from economic uncertainty and geopolitical crises, edging closer to annual sales of US $1 trillion at the end of 2017. -

Cerved Official Document

COMPETITORS ITALY CLOCKS AND WATCHES November 2012 INTRODUCTION TO METHODOLOGY Databank's methodology for Competitors reports begins with a careful screening to identify the main organisations that are representative of a given sector. Several one-to-one interviews are then conducted with the selected organisations. Questionnaires are sent to all the leading companies on an annual basis. The information collected is then verified by an expert in the particular sector using a system of counterchecks to guarantee that the information is entirely reliable and consistent. The process is then completed using Cerved Group's proprietary information about Italian enterprises. All Competitors reports also include details concerning the strategies and performances of the leading companies in each sector. Wherever no specific source is indicated, the information published in these reports can be assumed to have been taken from Cerved Group's proprietary information bank. Coverage of any sector in Competitors products may be used in company presentations or in training courses on the subject. www.databank.it SECTOR DESCRIPTION Scope This report covers various kinds of watches and clocks. • Product technology Based on the timekeeping technology, three main types of clocks can be distinguished: mechanical clocks, which can in turn be divided into those powered manually (by winding) and those powered automatically; quartz clocks, where the passage of time is measured using the oscillations of a quartz crystal; clocks with complex movement mechanisms, such as those with functions beyond indicating hours and minutes (e.g. the exact date even in leap years, lunar cycles and stopwatch functions). The most difficult mechanisms to produce include minute repeaters (tones that signal each minute) and the tourbillon (an additional mechanism used to regulate the timekeeping device to counter the effects of gravity). -

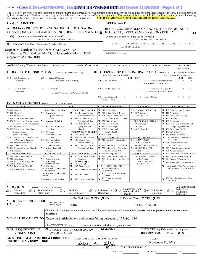

Case 0:18-Cv-62790-DPG Document 1-1 Entered on FLSD Docket 11/16/2018 Page 1 of 1 Case 0:18-Cv-62790-DPG Document 1 Entered on FLSD Docket 11/16/2018 Page 1 of 63

Case 0:18-cv-62790-DPG Document 1-1 Entered on FLSD Docket 11/16/2018 Page 1 of 1 Case 0:18-cv-62790-DPG Document 1 Entered on FLSD Docket 11/16/2018 Page 1 of 63 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA AUDEMARS PIGUET HOLDING SA, BREITLING U.S.A. INC., CHANEL, INC., GUCCI AMERICA, INC., HENRI STERN WATCH AGENCY, INC., HUBLOT SA, GENÈVE, COMPAGNIE DES MONTRES LONGINES, FRANCILLON S.A., MOVADO LLC, OMEGA SA, RADO UHREN AG, TURLEN HOLDING SA, and LVMH SWISS MANUFACTURES SA, Plaintiffs, vs. BLUELANS, CHENGLIAN, CRAZY STORE, ENGHUANIU, ETHEREAL, EVERGRAND, FASHION&PRETTY, FLEECEBOO, GUOMIAOMIAO1314, HERUN INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD., ZHEJIANG, JIANGLINA, JIANGQIONG STORE, JINGJIANSTORE, MENGHONGYAN, MINGXINGBIAOYEYOUXIANGONGSI, MONTH CLOUD, ROADTOALLWAYS, SHENZHENSHIQINGMEIKEJIYOUXIANGONGSI, SHIXIN888999666, SILVER CHINESE, TOPBIRDY, WEIYE, XINLINGZHONGBIAO, YICHENG TESCO, GOD BLESS US & MY TIME ZONE STORE, MY TIME ZONE, WATCHESTIME, BEST4CHOOSE, CORPOR2008, GUDAOXIAGU-0, JOFTBENN7, KHER6424, MIKI2016, SPRINGENN, FAFAFA8886, KISSCOME0411, LEEHOMWANG, PAYCAY, VIVAQ8, WRISTWATCHESHERE, ZHIMAKAIHUA2015, BAGAHOLICS20000, BESTWATCHES88, HB_LUXURY_BAGS, HYPE_REPLUG, LUXURY_BAG_SHOES_SHOP, LUXURYBRAND.FACTORY1314, LUXURYGIRL9328, MSHOP8_TEL_89516445438, ROLEXFULLDIAMANTES, ROLEXWATCH2018, WATCH_HAPPENS, WATCHESPAGES, PHAN.OFFICIAL9 a/k/a PHANOFFICIAL.COM, XFASHION_BOUTIQUE222 a/k/a KINGLUXURY222.COM, CLASSEMPORIUM.COM, and SWISSREPLICAWATCHESININDIA.COM, each an Individual, Partnership, Business Entity, or Unincorporated Association, Defendants. -

Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2020 the New Age of Fashion and Luxury Contents

Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2020 The new age of fashion and luxury Contents Foreword 3 Quick statistics 4 The new age of fashion and luxury 5 Top 10 highlights 17 Top 100 24 Geographic analysis 31 Product sector analysis 37 New entrants 42 Fastest 20 43 Study methodology and data sources 45 Endnotes 47 Contacts 50 Foreword Welcome to the seventh edition of Global Powers of Luxury Goods. At the time of writing, the COVID-19 pandemic has inflicted many losses: human, social and economic. What we are now experiencing is an unprecedented moment of crisis in modern history. However, it is during uncertain times that companies often come up with new ideas, converting the crisis into an opportunity, and adopting a long-term vision of future challenges. This prolonged disruptive situation is creating profound changes in consumer behavior and how companies are responding to these changes—prompting a debate about the future of the fashion and luxury industry. There is a general feeling of rethinking luxury and driving it in new directions, considering which business models will be feasible and more relevant in the new normal. Tradition and responsiveness, two elements that have always characterized luxury companies, will both be required to face great challenges in the post-COVID environment. We see the pandemic acting as a divider between the old way of doing business and the new scenario that is taking shape, characterized by changing consumer behavior. Hence, in this report, we talk about a new age for fashion and luxury and will explore the main trends that will drive the industry in the coming months. -

Press Release Patek Philippe, Geneva April 2021 Ref. 5236P-001 In-Line Perpetual Calendar Patek Philippe Introduces a Totally Ne

Press Release Patek Philippe, Geneva April 2021 Ref. 5236P-001 In-line Perpetual Calendar Patek Philippe introduces a totally new perpetual calendar with an innovative patented one-line display The manufacture has expanded its rich range of calendar watches with the addition of a perpetual calendar that displays the day, the date, and the month on a single line in an elongated aperture beneath 12 o'clock. To combine this unique feature with crisp legibility and high reliability, the designers developed a new self-winding movement for which three patent applications have been filed. This new in-line perpetual calendar premières in an elegant platinum case with a blue dial. As classic grand complications par excellence, perpetual calendars have always been prominently featured in Patek Philippe’s collections. In 1925, the Genevan manufacture presented the first wristwatch with this highly elaborate complication (movement No 97’975; the watch is on display at the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva, No. P-72). Patek Philippe perpetual calendars offer a wide range of design elements with analog or aperture displays and dial configurations. Models with the famous self-winding ultra-thin caliber 240 Q movement, such as the Ref. 5327, can be recognized by their day, date, and month displays in three separate subsidiary dials. The self-winding caliber 324 S Q, which among others powers the Ref. 5320, exhibits another traditional face among the manufacture’s perpetual calendars. It features a dual aperture for the day and month at 12 o'clock and a subsidiary dial at 6 o'clock for the analog date and the moon-phase display. -

200612__Sabrina Weber Thesis

LUXURY BRANDS AND CRM, MUTUALLY EXCLUSIVE? – DEVELOPING A CRM STRATEGY FOR PATEK PHILIPPE Sabrina Weber Project submitted as partial requirement for the conferral of the Master of Science in Business Administration Supervisor: Manuel Lopes da Costa, CEO HP Portugal April 2012 – Sabrina Weber Sabrina DEVELOPING A CRM STRATEGY FOR PATEK PHILIPPE PATEK FOR STRATEGY CRM A DEVELOPING LUXURYBRANDSMUTUALLY ANDCRM, EXCLUSIVE? Abstract in English Nowadays consumers get more demanding than ever before, marketing moves from the traditional transactional driven paradigm to the new, relational based paradigm. That is why customer relationship management (CRM) gains importance. Conventional brands were the first one’s that implement a CRM strategy in order to built strong long-life relationships with the most valuable customers. Luxury brands are just starting to realize the benefits of CRM. Whereas they are reluctant to use the usual and common techniques that have been proven successful for classic consumer goods because it involves the risk for luxury brands to loose its prestige status. Hence, luxury brands are facing the challenge to reconcile CRM and at the same time, keeping their luxury image. This work intents to answer the question if luxury brands and CRM are mutually exclusive or not based on the case study of developing a CRM strategy for the luxury brand watch company Patek Philippe. This case study is not conducted in cooperation with the company Patek Philippe that is why the type of case data used in this work is data available in the Internet, books, magazines or lectures. To answer the work’s question, theoretical knowledge gets applied to a real life situation by the reference of the case study of Patek Philippe. -

Craftsmanship and Precision Competition” : an Eleventh Edition Under the Sign of Excellence

Patek Philippe Geneva June 2021 The Patek Philippe “Craftsmanship and Precision Competition” : An eleventh edition under the sign of excellence To encourage promising young talent and help train the next generation, Patek Philippe created in 2010 a timing and adjusting watch competition intended for students of Swiss watchmaking schools. The 2020 edition was canceled due to the Covid-19 pandemic, but Patek Philippe wished to maintain the 2021 edition by adapting it to these exceptional circumstances, and thus pursue the fruitful partnership with Swiss watchmaking schools. A Patek Philippe timepiece is intended to be passed on from generation to generation. Similarly, the skills required to create such fine timepieces must also be carefully preserved and constantly fostered. As a guardian of this know-how, the Geneva Manufacture continuously trains watchmakers in its workshops. Since 2010, it has also been engaged in a long-term partnership with Swiss watchmaking schools. This is how the Patek Philippe “Craftsmanship and Precision Competition” was born. Designed to motivate the new generation, this watchmaking award stands out thanks to its educational approach. Offering a total immersion in the world of fine watchmaking, it aims to raise awareness among future experts of the concept of craftsmanship by offering them the unique opportunity to examine a high-end caliber, all of the components of which have been manufactured and finished with utmost care. An Adapted Contest Format In order to maintain the level of quality and expectations of the Competition, while respecting the sanitary procedures in force, it was agreed that the contestants would not go to Patek Philippe in Plan-les- Ouates, but rather that the organizing committee of the competition would visit the schools. -

Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2020 the New Age of Fashion and Luxury Contents

Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2020 The new age of fashion and luxury Contents Foreword 3 Quick statistics 4 The new age of fashion and luxury 5 Top 10 highlights 17 Top 100 24 Geographic analysis 31 Product sector analysis 37 New entrants 42 Fastest 20 43 Study methodology and data sources 45 Endnotes 47 Contacts 50 Foreword Welcome to the seventh edition of Global Powers of Luxury Goods. At the time of writing, the COVID-19 pandemic has inflicted many losses: human, social and economic. What we are now experiencing is an unprecedented moment of crisis in modern history. However, it is during uncertain times that companies often come up with new ideas, converting the crisis into an opportunity, and adopting a long-term vision of future challenges. This prolonged disruptive situation is creating profound changes in consumer behavior and how companies are responding to these changes—prompting a debate about the future of the fashion and luxury industry. There is a general feeling of rethinking luxury and driving it in new directions, considering which business models will be feasible and more relevant in the new normal. Tradition and responsiveness, two elements that have always characterized luxury companies, will both be required to face great challenges in the post-COVID environment. We see the pandemic acting as a divider between the old way of doing business and the new scenario that is taking shape, characterized by changing consumer behavior. Hence, in this report, we talk about a new age for fashion and luxury and will explore the main trends that will drive the industry in the coming months.